Sydney Baker moved back to the US during a wildfire season like no other, breaking out in sore, red rashes and acne as she witnessed her hometown burn. Then she began listening to what these flare-ups tell us about the state of the world and our health within it.

Last year I returned to Seattle, where I grew up, at the end of the wildfire season. Home, yet again, was up in flames. It wasn’t always like this.

The burning forests seem to inch closer and closer to Seattle’s populated centre each year. The fires have become much bigger, more volatile, and produce smoke so thick that it can be mistaken for fog rolling in from the ocean.

These toxic plumes of smoke coat the western skies for weeks. But in 2021, western wildfire smoke spread so far that people on the East Coast – as far as New York and Quebec – had air-quality warnings.

I was constantly monitoring the quality of the air to see if it was safe to go outside – something I did not do growing up; a testament to how much our daily lives are changing because of the climate disaster.

I’d check the air-quality section of my weather app before looking to see the temperature or chance of rain. I’d cross-check those ratings with other sources that also let me know which activities were safe – or not – to do that day. In the morning, along with my favourite travel blogs and newsletters, I would read the Washington Smoke Blog and follow meteorologists on Twitter with the dedication of a professional storm tracker.

I have learned that anywhere between 0 to 50 on the Air Quality Index (AQI) is a healthy rating. But during what the Seattle Times called ‘Smoketober’ – after the mass of smoke exposure in October 2022 – the AQI was often well above 50 and we were recommended not to exercise outdoors by the US government agency Air Now. On bad days, the AQI would break 150 (marked “unhealthy”) or even 200 (“very unhealthy”).

I found myself in voluntary quarantine, reminiscent of 2020, except this time it was poisonous fumes in the air that I was avoiding.

“I was constantly monitoring the quality of the air to see if it was safe to go outside.”

It prompted the advice from other local health agencies, like the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency, to avoid going outside if possible. And so I found myself in voluntary quarantine, reminiscent of 2020, except this time it was poisonous fumes in the air that I was avoiding.

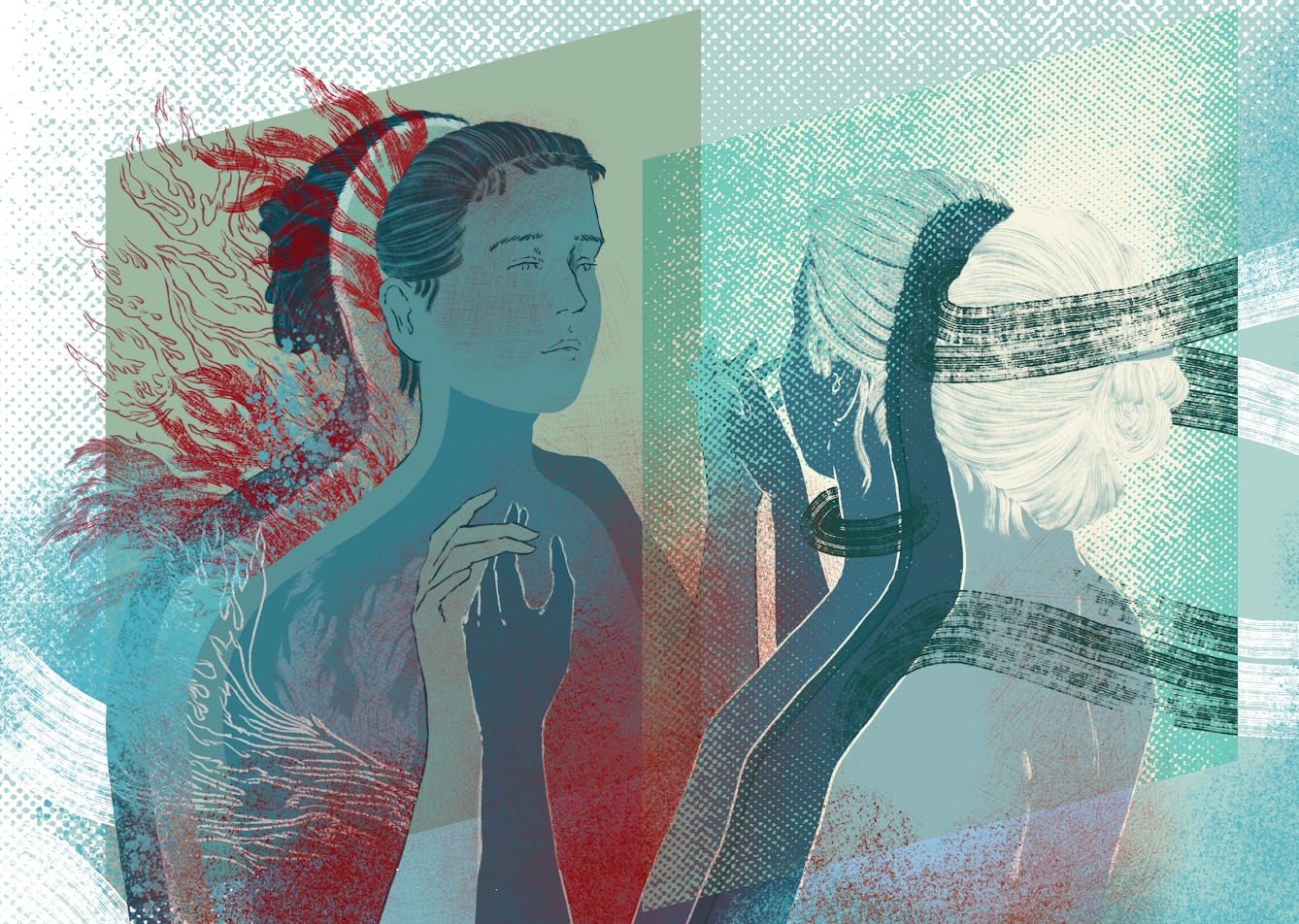

My body’s response to toxic air

When I did go outside, the toxic smoke choked the air, my lungs, and my hope for the future. This manifested in obvious ways over my body. Not only were the mountains and trees I grew up among on fire, but so too was my skin.

It started with red blotches on my arms and chest. Then my acne flared up, something that I’d had (more or less) under control for years.

And then, seemingly overnight, my scalp became inconsolably irritated and had me picking at it constantly. No matter how much I knew that would only make the conditions worse, I didn’t have another coping mechanism for the pain, anxiety and fear I felt.

The rashes, acne, and itchiness would intensify on particularly poor-air-quality days. These flare-ups would then recede during periods of clearer skies, usually following strong winds that blew away the toxic particles that polluted the air.

As the fires continued to rage, so did my skin issues. New rashes and irritations came and left in conjunction with the smoke.

“It started with red blotches on my arms and chest. Then my acne flared up, something that I’d had under control for years.”

The last time my skin responded similarly was in 2020. The pandemic – particularly the extremely uncertain first few months – followed by the 2020 election season in America, highlighted the sheer scale of structural racism and inequality in this world. It was stress unlike anything I had ever experienced. On top of that, I was dealing with moving countries, freelancing in earnest, and living with my parents while I figured out my next move. My body erupted in the form of an itchy scalp and red patches over my arms – it was warning me of danger.

Our skin follicles can release inflammatory hormones in response to hazards they encounter every day – things like dust, make-up, and yes, wildfire smoke.

And these skin problems can be at the intersection of our mental and physical health. As much evidence shows, there is a clear “brain-skin connection”.

But doctors believe it is more than a simple cause-and-effect formula, where external stressors lead to skin issues. Rather, both influence each other: stress can lead to skin reactions and in turn, skin problems increase stress. This is what I see playing out in my own life.

In heading back home, I have learned that the largest and most visible organ of my body – my skin – has been trying to tell me that the world is in pain. And I will probably have to continue adapting my lifestyle to protect my mental and physical health within it.

Yet my flare-ups are linked to global structural injustices – like climate change and inequality – that feel out of my control, and making small-scale changes to my life will only get me so far if the world continues to burn.

That is why I am so frustrated with the politicians and elites who hoard wealth and power, who deny the multiple crises we face and refuse to protect planet and people. The earth takes care of us just as we must take care of her and those living on her – and my skin won’t get any better until we do.

About the contributors

Sydney Baker

Sydney is a freelance writer from Seattle with a background in immigration and international education at higher-education institutions. She has lived in Sydney, Montreal and Luxembourg, travelled solo across four continents, speaks French and a little German, and is always on the lookout for her next adventure. She writes about travel, lifestyle and language.

Cat O’Neil

Cat O’Neil is an award-winning freelance illustrator, specialising in editorial. She studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2011, and has lived in Hong Kong, London, Glasgow, Lyon and Edinburgh. Her clients include the New York Times, Washington Post, WIRED, LA Times, Scientific American, the Financial Times, the Guardian/Observer, Libération and more. Her work explores the use of visual metaphors to convey concept and narrative, and combines the use of traditional and digital mediums. Much of her recent work includes the creation of 3D paper sculptures, which are made in her studio in Edinburgh.