Just before receiving residential treatment for OCD, Rachel May found that she couldn’t write, and used quilting and embroidery to express her feelings instead. Her chosen medium, she reveals, was like that of the quiet revolutionaries who, incarcerated and classified as ‘lunatics’, spoke their truth with embroidery needles.

In 1893, when Lorina Bulwer was single, at 55, and her parents had died, her brother sent her to the Great Yarmouth Workhouse. There, she was “classified as a ‘lunatic’”.

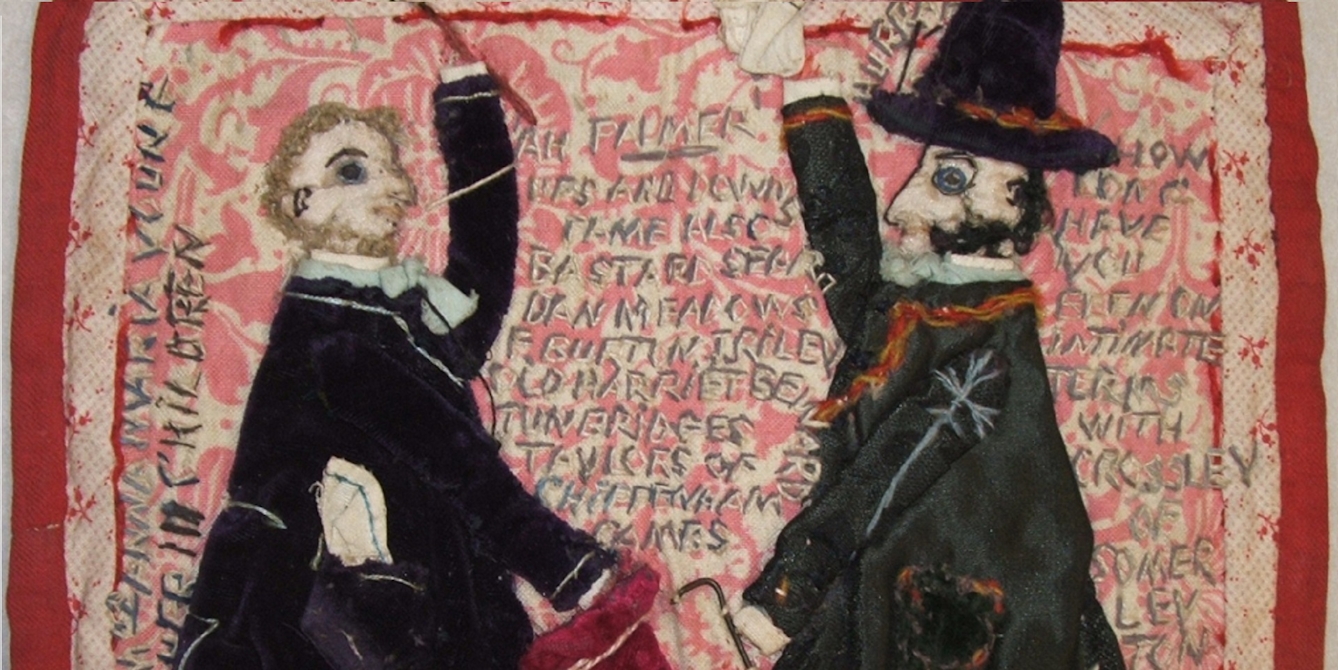

Lorina lived there until she died in 1912. She was furious she’d been cheated out of money and sent to the workhouse forever. She made statements like the following in a series of scrolls embroidered with her all-caps words:

I HAVE WASTED TEN YEARS IN THIS DAMNATION HELL FIRE

Embroidery, Lorina Bulwer.

It seems that in her fury, and with no other way to speak her story, Bulwer turned to stitching, appliquéing scenes and embroidering letters onto fragments of fabric that she pieced together.

Often, stitched pieces were lost to overuse or disregard, but somewhere along the way, someone recognised the importance of Lorina’s stitching, and preserved her objects so that we can view and read them today. They serve as both pieces of art and relics of her voiced experience in the face of those who had attempted to silence her.

Sewing as silencing

In the Victorian era, when Lorina Bulwer lived, middle-class women were expected to fulfil their duties by beautifying the house with their stitched samplers, doilies and embroideries. They proved their class with these objects, the making of which filled their time.

Victorian women were kept out of trouble – writing, education, political organising, and anything else that might threaten men’s realm of responsibility – with their stitching, conscripted to a new kind of constant housework: patchwork, needlework, crewelwork.

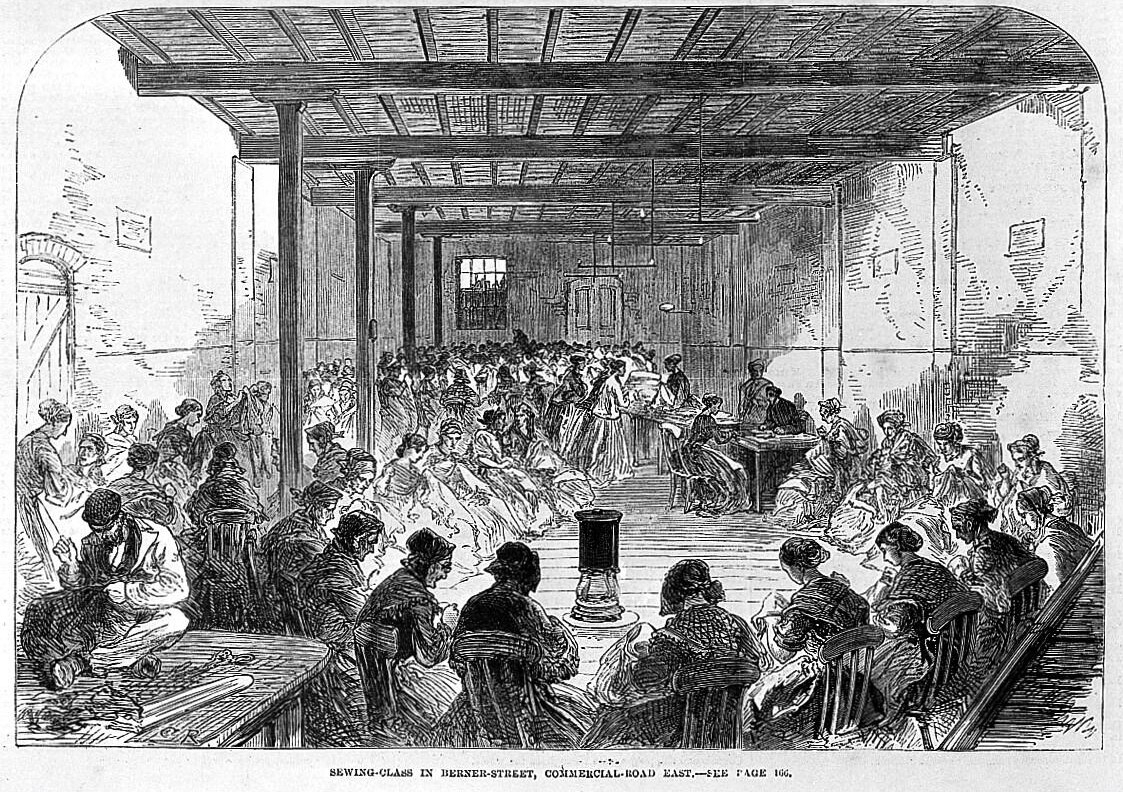

The Factory Act of 1833 mandated education time for child workers, and that for girls, much of that time was “devoted to needlework”. In the image above, two rooms are pictured: one with men who chip away at rocks, and the other with women hunched over their embroidery, all hard at work during the ‘distress’ in 1868 London.

While the middle and upper classes were indoctrinated with embroidery, they, in turn, taught the poor the same skills as tools to earn a living. “Once embroidery had become an accepted tool for inculcating and manifesting femininity in the privileged classes, with missionary zeal, it was taken to the working class,” writes historian Rozsika Parker.

Women didn’t have to be suffering from mental illness to be labelled ‘lunatic’ and sent to an asylum or workhouse. In some cases, women labelled ‘lunatic’ may well have merely been too outspoken for their relatives’ liking, or troublesome in some other way. Lorina testified to that in her scroll:

MAD MOLLY SHE WAS SENT TO PRISON FOR THREE WEEKS FOR INSULTING Mrs OR MISS BOULTER CONFECTIONER NORTH GATE STREET

Nineteenth century patchwork, embroidered scroll, Miss Lorina Bulwer of Great Yarmouth.

A workhouse for the poor, an asylum – these were convenient repositories for ‘troublesome’ women; sending them away was one way to effectively stitch their mouths shut.

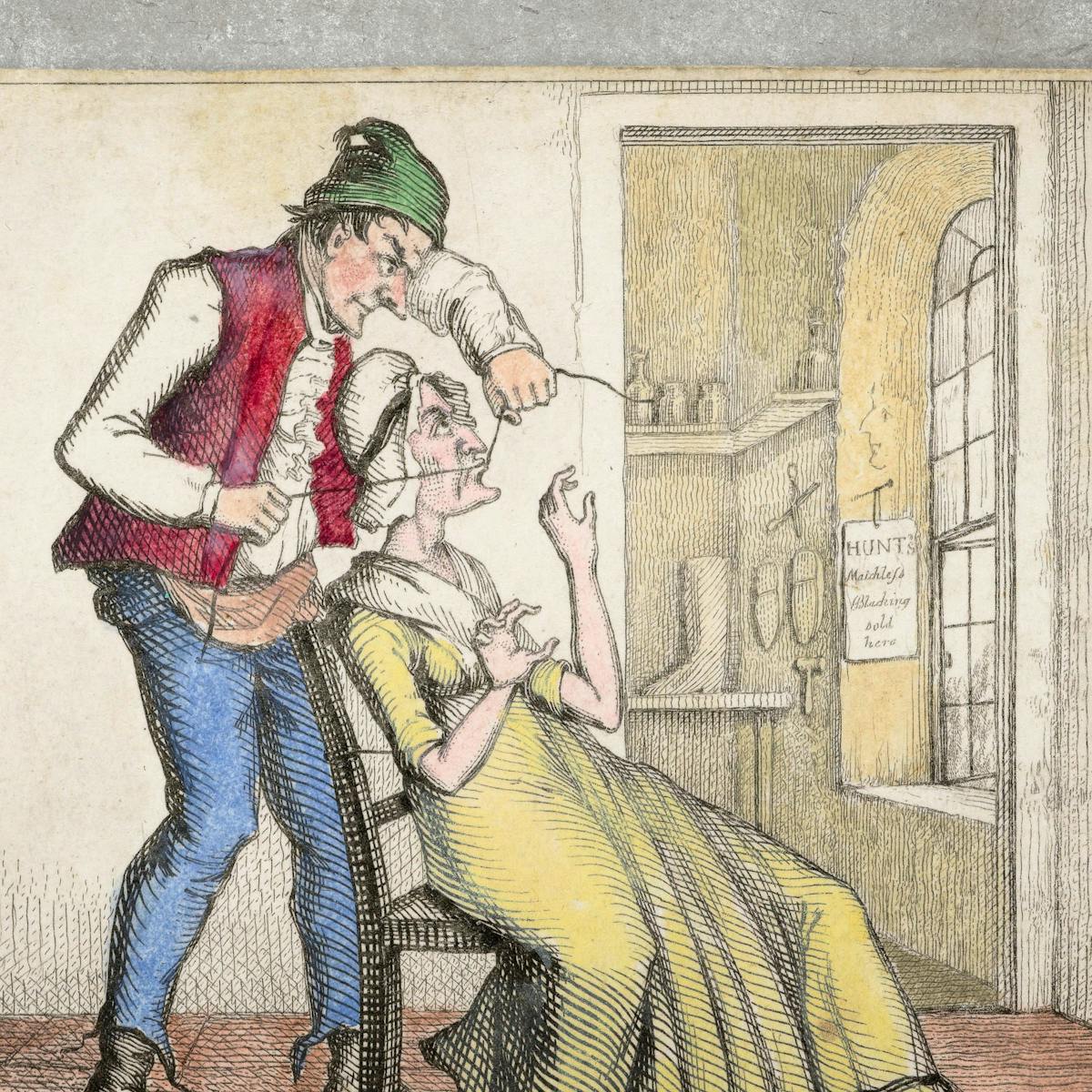

A shopkeeper sews up his wife's mouth to stop her from nagging, Thomas Lord Busby.

Stitching a subversive story

In Lorina’s day, a female patient at an asylum wouldn’t have been permitted to write her story with pen and paper. But the Barbazon Scheme encouraged female workhouse inmates to use handicrafts as occupational therapy. Perhaps this is why Lorina was allowed to stitch the samplers.

As Parker explains, historically, many women have subverted the Victorian feminine norms in the very stitching meant to inculcate them. Lorina is one of those subversive stitchers who turned her needle, thread and fabric into tools to tell her story.

Agnes Richter was also confined to an asylum where she stitched her protest. A trained seamstress, she was somehow permitted to design her own clothes out of the asylum’s wardrobe, and then embroidered words on them.

The Little Jacket (1895), Agnes Richter.

Psychologist and author Gail Hornstein suggests that Lorina’s stitching is in keeping with traditional sampler work, while Agnes’s writing “is not neat. It is not feminine. It is an angry testimony.”

Though it may be neater, I’d argue that Lorina’s is an angry testimony as well, where she makes her arguments about her standing as a patient, her finances, and her observations of other patients clear. She chose to make her letters all caps, which is a faster method than the curves of lower-case letters. It also emphasises her strong voice, her insistence that she was being cheated of money and that life at the workhouse was difficult, at best.

Curator June Hill argues that Lorina’s words are “Written entirely in capitals and with no punctuation… the urgency of what is being said is as palpable as the anger.” Lorina is what cultural theorist Sarah Ahmed calls a “willful subject”, someone who speaks out against injustice, making her voice known. Ahmed calls her a “feminist killjoy”.

Soothing stitches

I don’t believe I’d seen Lorina Bulwer’s and Agnes Richter’s work before I went for residential treatment for OCD at the McLean Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, where poets Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton had once sought care.

I’d always been a writer, but suddenly just after my diagnosis a year earlier, I couldn’t write. I found, as Lorina and Agnes had before, that sewing pictures and stitching embroidered words became my only way of expression. I’d stay up late at night, alone, sewing quilts and then making my appliequéd story with the scraps.

Embroidery, Dr Rachel May.

Finally, I had a way to channel my rage – for missing out on so much of my life because of undiagnosed OCD – into a medium. Telling the story in fabric helped me direct my anger not at myself but at OCD. The figure screamed at the ‘monster’, as I came to see OCD, facing it, challenging it, and finally, disarming it.

As I underwent treatment, there was something about handling the fabric, the bright colours, listening to the shhhh of the needle and thread through the cloth, the sharp rip of a fabric along the grain, that calmed me. Sitting in long meetings and therapy sessions, it helped to keep my hands busy with needle and cloth; it gave me a place to focus, a tangible connection to the real world – the tactile – as I worked through what felt like the vast abstract territory of my own history and psychology, and confronted all my fears. The cloth was comfort.

Embroidery, Dr Rachel May.

There is a “healing pleasure from the both the tactile properties of textile crafts and the rhythm of the repetitive motion involved”, and art therapists have noted how working with textiles, specifically “fabric collage”, like those I made, in the same spirit as Lorina, is helpful for treating trauma. The work is “relational and rhythmic”, and can be “soothing and nurturing”.

I don’t know if Agnes and Lorina found that to be true. I imagine that as women who were raised from a young age with a needle and cloth in their hands, it must have been a comfort to be able to continue sewing, doing the work that had always been a part of their identity and training, the motions living in their muscle memory. To use it to tell their stories with text, when they couldn’t pen their stories, was innovative genius.

Speaking out via stitching

Throughout the pandemic, after many people bought sewing machines and learned to stitch to make masks, they found in sewing a therapeutic tool. They, too, felt less alone by engaging with a tactile process at a time when touching wasn’t allowed. And many went on to find that the medium gives them voice.

Today, we see “feminist killjoys” embodied in the hundreds of subversive stitchers who post to Instagram and show their work in museums, bringing to the fore issues of racial justice, abortion rights, LGBTQ rights, among many others. For example, the Tiny Pricks Project started as a protest against Trump by embroidering his words on old handmade handkerchiefs and doilies, and lives on as a collective online space for justice work.

Like their predecessors, these sewists use their tools to tell their stories. Whether they know it or not, they are carrying on the legacies of women like Lorina Bulwer, Agnes Richter and the thousands of unnamed embroiderers – nurses, poorhouse workers and others – who spent their days making embellishments and words with their hands, transforming thread and cloth into flowers, letters, seams, and evidence of their lives.

About the author

Rachel May

Rachel May is the author of ‘The Experiments: A Legend in Pictures & Words’, which tells the story of her diagnosis and treatment for OCD in allegories and sewn pictures, ‘An American Quilt: Unfolding a Story of Family & Slavery’, and ‘Quilting with a Modern Slant’. Her recent work has been published in the New York Times, National Geographic, Outside, LitHub, and Guernica.