While total abstinence for holy people was a popular idea in the Middle Ages, the established attitude to sex for the general population – not too much, not too little, and only between married heterosexuals – reflected ideas about its importance to a healthy lifestyle. Historian Katherine Harvey explores the perennial issues sex presents, and how medieval societies dealt with them.

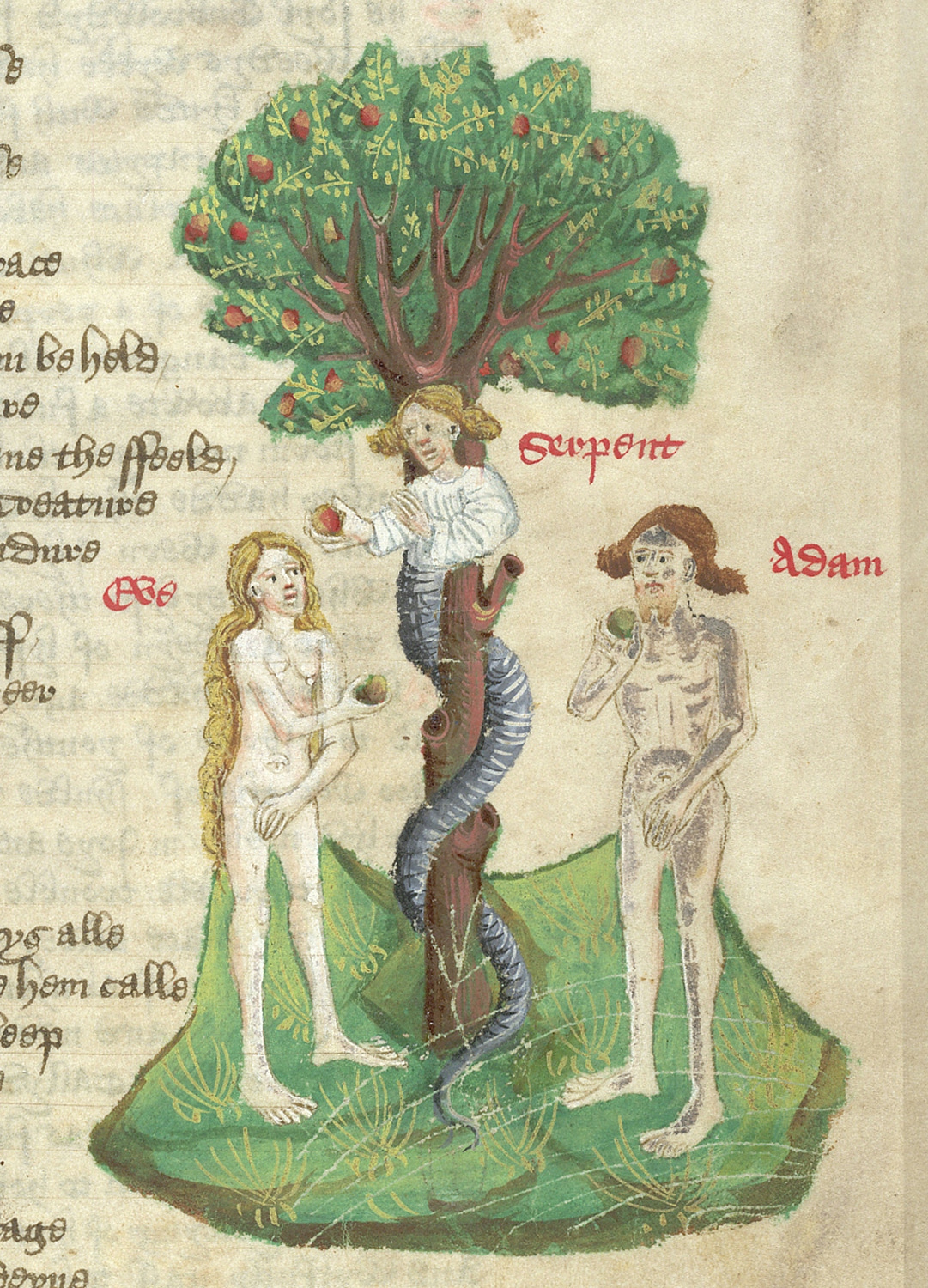

Medieval ideas about sex were heavily influenced by Christian beliefs. The Catholic Church taught that after Adam and Eve were thrown out of Eden, sex became tainted by lust. Holy men and women preserved their virginity in emulation of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and countless saints, and all Christians were taught that sex was a potential source of sin. Nevertheless, the Church could be surprisingly forgiving of repentant sinners such as Mary Magdalene, who was one of medieval Europe’s most popular saints.

Medieval ideas about sexual health were shaped by humoral medicine, specifically by the belief that sickness was caused (and health preserved) by the expulsion of bodily fluids. For this reason, sex was part of a healthy lifestyle, but only in moderation: too much or too little could cause serious illness or even death. Venereal diseases were often attributed to sexual excess, and it was widely believed that leprosy could be sexually transmitted. Medical treatises recommended the application of various substances (from vinegar to quicklime) to diseased genitals.

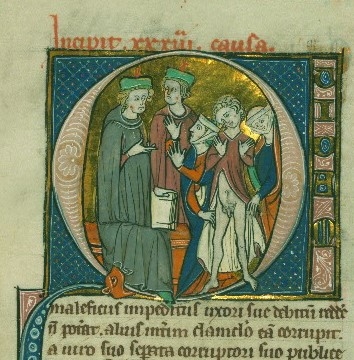

Sex played an important part in medieval marriage, with spouses owing each other “the marital debt”. This meant that sex could only be refused for specific reasons, such as advanced pregnancy or insanity. Impotence was one of the few justifications for annulling a marriage, but such separations were difficult to obtain, and the couple might be subjected to intimate physical examinations. Despite the importance of marital sex, a small number of couples mutually agreed to abstain for religious reasons, but often, as in the case of 15th-century Norfolk couple Margery and John Kempe, one spouse was more enthusiastic than the other.

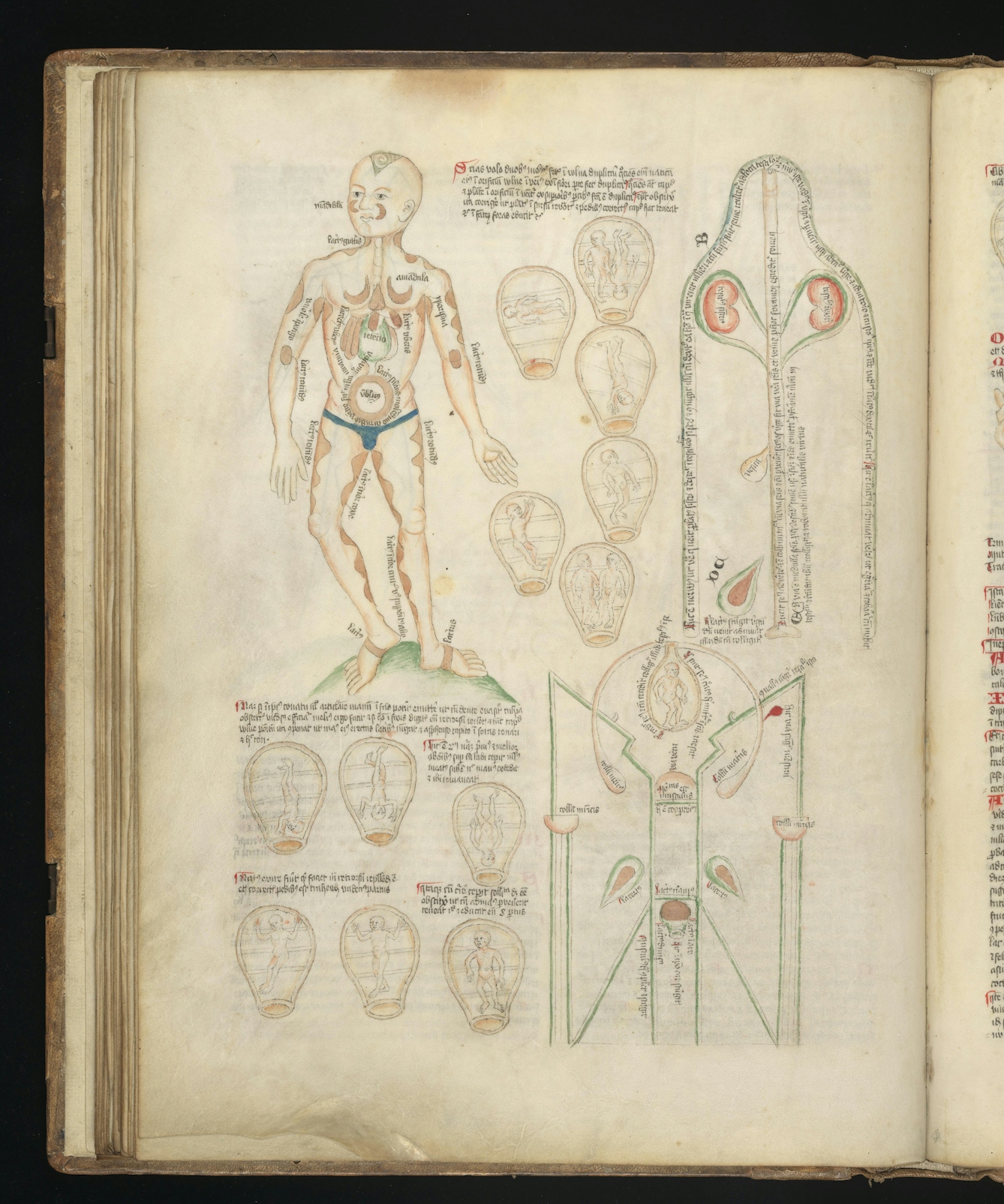

Although most medieval people expected to have children, they didn’t just passively accept their reproductive destinies. Medical treatises offered advice on how to conceive; since it was widely believed that conception occurred only when both partners produced seed, there was a surprising emphasis on sexual pleasure. Other couples tried to avoid pregnancy, using methods designed to prevent the mixing of seed (including coitus interruptus, post-coital sneezing, and anointing the genitals with oil), or herbal remedies believed to cool the body and thus to reduce lust. Some women tried to terminate unwanted pregnancies by punching themselves in the stomach or by drinking purgative potions.

From the late 11th century onwards, all clerics (including monks, nuns and parish priests) were required to remain celibate. Some adopted extreme measures, such as frequent fasting, immersion in freezing water, or even self-castration. Others failed to keep their vows – although few failed as badly as Jean de Heinsberg, Bishop of Liège from 1419 to 1456, who reportedly had 65 children.

Men who had sex with men were widely viewed as sexual deviants, with their sinful desires blamed on physical deformities or formative teenage experiences. Most of the surviving evidence for sexual relationships between men is found in court records, notably those of the Office of the Night, which uncovered thousands of cases in 15th-century Florence. Most involved casual sex, but there were also some loving, long-term unions. Female-to-female attraction is almost, but not entirely invisible: cases such as that of Guercia, who was banished from Bologna in 1295 for having sex with other women using a dildo-like device, give us tantalising glimpses of medieval lives.

According to the Church, the only acceptable sex was marital intercourse, preferably in the missionary position and for the purposes of reproduction. Everything else – including sex in other positions, and masturbation – was classed as ‘sodomy’ and viewed as a sin. Having non-marital relations of any kind could lead to a court appearance, a humiliatingly public punishment, or even (in rare cases) the death penalty. Relationships with people of other religions were also discouraged, and could be harshly punished.

Medieval attitudes to prostitution were complicated: the Church condemned the sale of sex, and established convents for reformed prostitutes, but medical theory suggested that a brothel visit might sometimes be beneficial to a man’s health. Urban authorities often took a surprisingly pragmatic approach. In the decades around 1300, many towns stopped expelling prostitutes and began to establish civic brothels and official red-light districts in an attempt to contain the problem. Efforts were made to regulate the trade, and to protect sex workers, but problems such as trafficking, violent clients and exploitation by unscrupulous pimps were hard to prevent.

Contrary to popular belief, medieval people were extremely concerned by sexual violence, but (like us) they often struggled to deal with it effectively. Rape victims could seek justice, but the standards of proof were high: women were typically required to provide physical evidence of a struggle, along with witness testimonies, and victim-blaming was common. Unsurprisingly, it was hard to secure a conviction, and although rapists could be executed, courts typically imposed lighter punishments, such as fines. Child abuse was considered particularly repugnant, although powerful institutions were often quick to cover up crimes committed by their members.

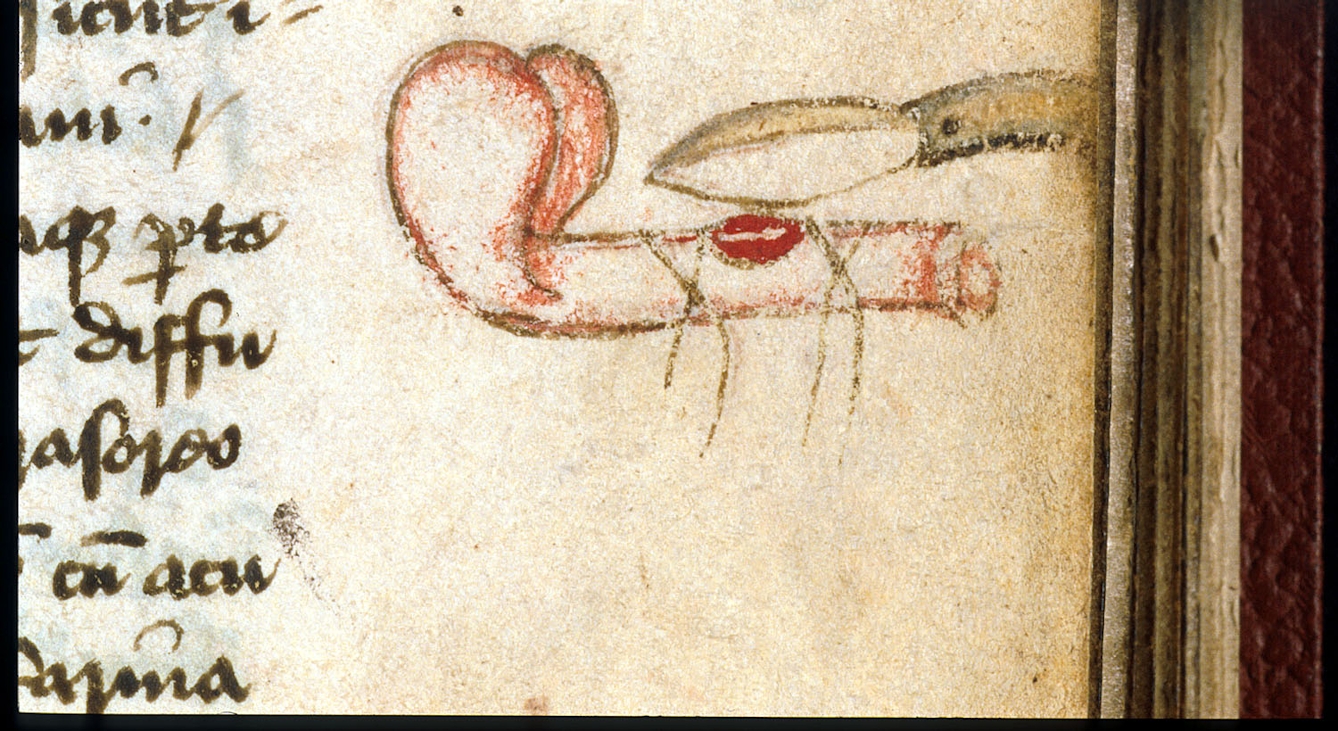

Although sex caused a lot of problems, it could also be a source of humour and fun. Medieval literature is full of bawdy stories about foolish husbands, lustful women and lecherous clerics. Genitals also feature prominently, both as standalone characters and as the subject of elaborate euphemisms. Art is equally explicit, with seemingly erotic sculptures (such as the grotesque Sheela Na Gig) displayed in churches, and crude drawings filling the margins of manuscripts. Obscene lead-tin badges, mostly featuring disembodied genitals, also survive in surprising numbers.

About the author

Katherine Harvey

Dr Katherine Harvey is a medieval historian based at Birkbeck, University of London. She is the author of ‘The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages’ (Reaktion, 2021), a Sunday Times Paperback of the Week. Her writing has appeared in publications including BBC History Magazine, History Today, The Sunday Times, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Atlantic.