Whether religious or not, most of us hope that our death will be a fitting testament to the moral and spiritual beliefs that guide our lives. Reflecting widespread environmental concerns, projects worldwide are offering new ways of dealing with bodies after death, with benefits for our natural surroundings.

In the 1990s Don Brawley and George Frankel were among a group of divers based at the University of Georgia whose job it was to sink jelly-mould-shaped concrete structures into the waters around Florida with the goal of rebuilding devastated coral reefs. For a decade they had planted these “reef balls” – roughly washing machine-sized and punctured all over with holes like Swiss cheese – when Brawley’s father-in-law told his family he was terminally ill.

His father-in-law, a pianist named Carleton Glen Palmer, said he had no desire to be buried “in a field with a bunch of old dead people”. He preferred the idea of being laid to rest in one of Brawley’s reefs.

Frankel, too, was sadly anticipating both his mother’s and brother’s deaths. “Her life was winding down,” said Frankel by telephone from Sarasota, Florida. “My brother had just been diagnosed as terminally ill, and had no desire of being sent back to New York to be part of the family plot. So my mind was wide open to Don's concept of putting his father-in-law's remains in a reef ball.”

Today, more than 2,000 people have been laid to rest in the 25 coastal rehabilitation projects along the USA’s eastern seaboard created by Eternal Reefs, the funeral non-profit that Frankel established. At many of these, the reef ball’s concrete is now scarcely visible, having been colonised by a patchwork of coral whose brain-like ridges and delicate fingers have transformed the monuments into a lively underwater metropolis. As Palmer wished, his remains are now in a reef in Sarasota, which dances with the rhythm of snapper and grouper.

“Traditional practices worldwide point to simpler ways of dying, which work with natural surroundings – and other animals.”

Be eaten by scavengers

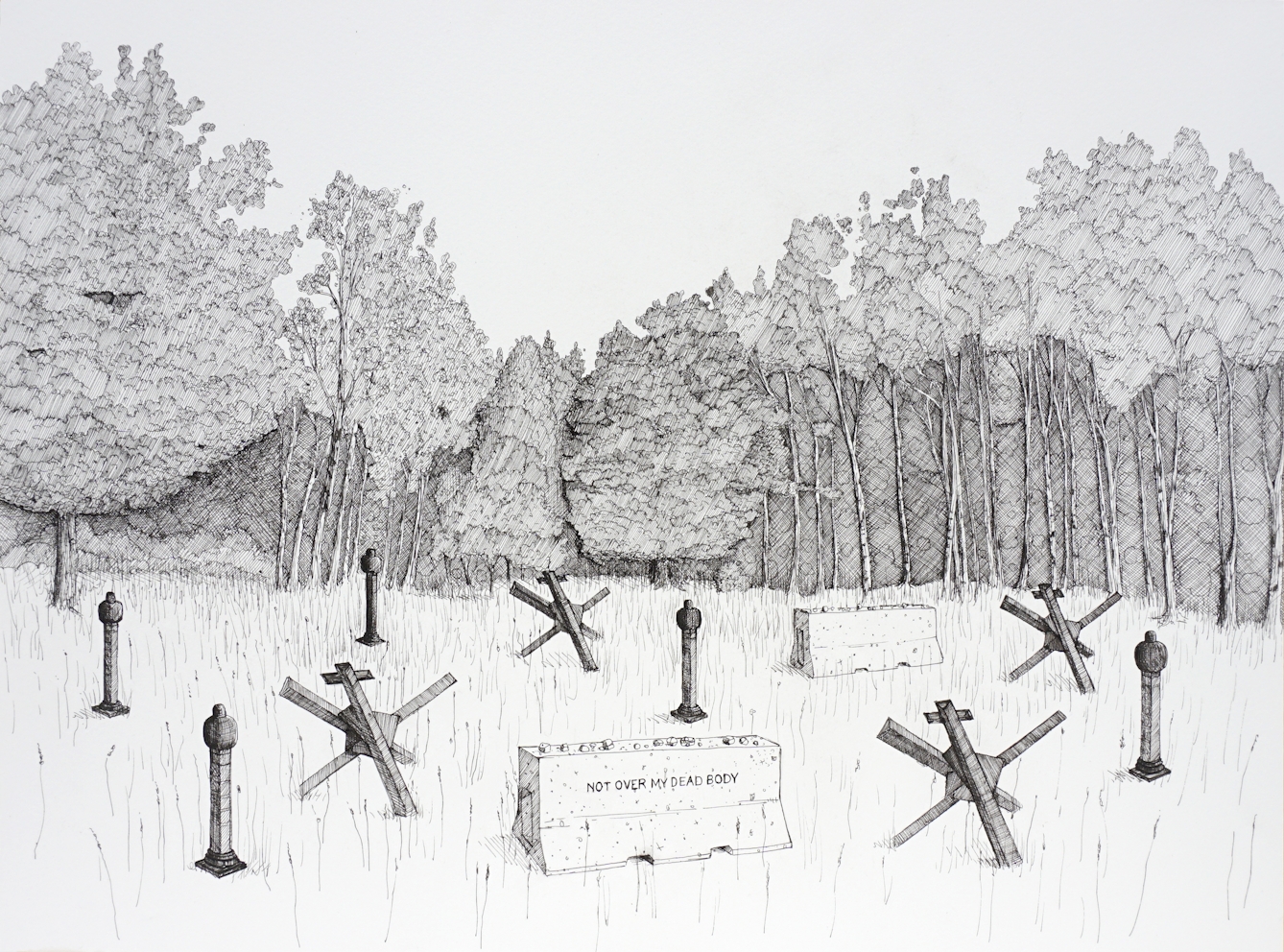

Globally, funerals spill millions of litres of carcinogenic formaldehyde into waterways and soil each year and have been linked to high levels of heavy metals in drinking water, all while consuming millions of kilograms of hardwood, marble, copper and bronze. Transport and CO2 emissions are key concerns: British crematoriums produce as much carbon as a town of nearly 20,000 people.

But the burial rituals responsible for much of this waste, such as embalming and elaborate coffins, are a relatively recent development, with what has become the Western Christian norm being exported from America around the turn of 20th century.

Death has not always been so complex. Traditional practices worldwide point to simpler ways of dying, which work with natural surroundings – and other animals.

Across the world, widespread rituals hand bodies over to be consumed by scavenging carnivores. In Tibet, the practice of jhator, feeding a carefully butchered corpse to flocks of vultures, often translated as “sky burial”, was born out of local necessity: high in the Himalayas, terrain freezes solid and firewood for cremation is scarce.

The giving of one's body to feed the vultures is a last act of generosity to living beings.

“But there is a very Buddhist concept by which sky burials are understood,” writes Alex McKay, editor of ‘The History of Tibet’. “The giving of one's body to feed the vultures is a last act of generosity to living beings, with a Buddhist precedent – a popular myth tells how the Buddha in one incarnation gave himself to feed a hungry tiger.”

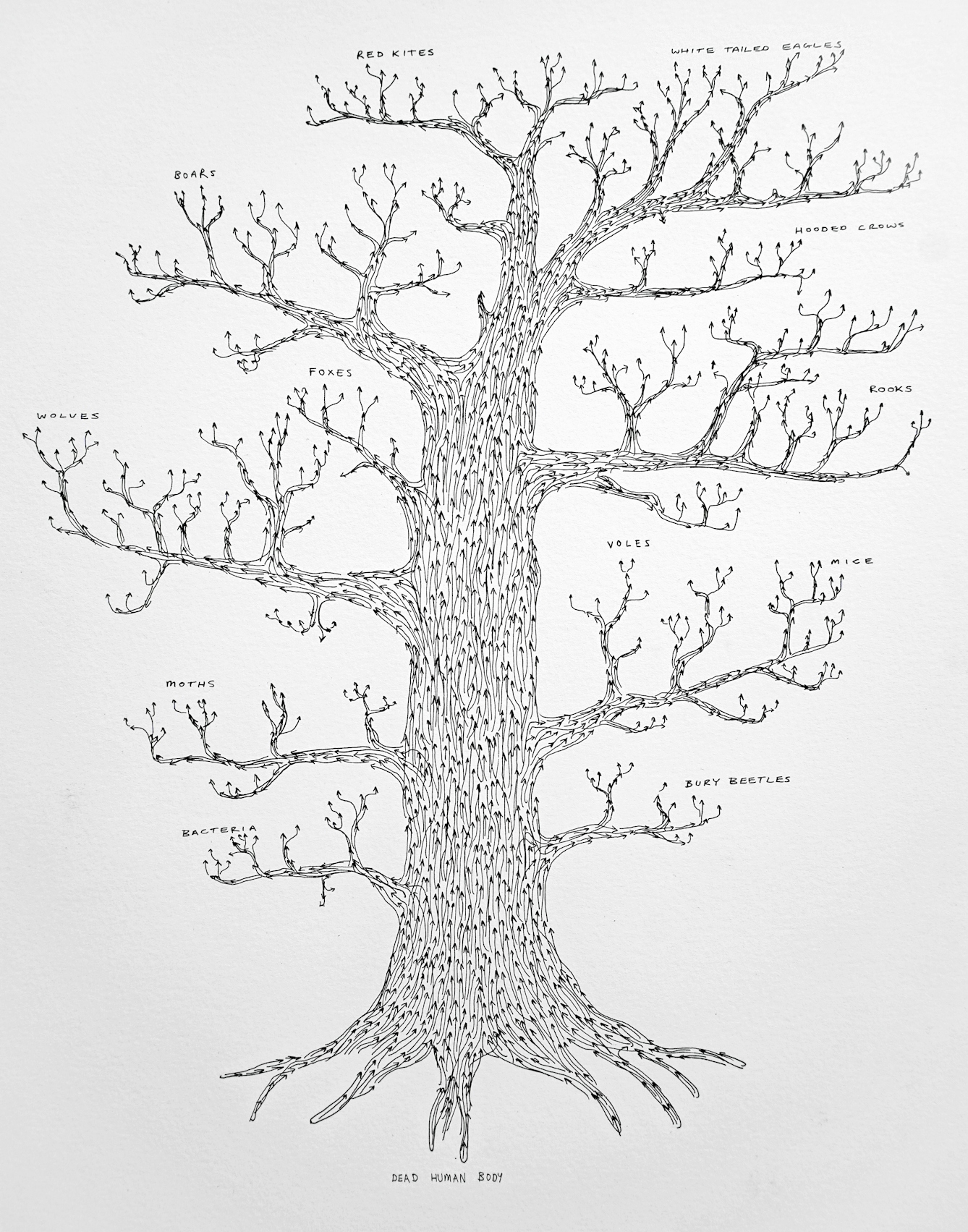

Densely populated cities, where the majority of the world’s people now live, are likely to be wary of such open scavenging. But there is evidence that bodies can be safely exposed to animals on urban peripheries, including in America’s “body farms”, research facilities where scientists study natural decomposition on donated bodies.

“Across the world, widespread rituals hand bodies over to be consumed by scavenging carnivores.”

Research at such farms highlights how many barriers to new burial practices are cultural and legal. The UK and some other European countries have no strict law preventing excarnation (the removal of flesh from bones before burial) – although it remains unclear if registered natural burial grounds would be allowed to deliberately expose bodies to carnivores.

In the US, however, “abuse of corpse” statutes typically forbid excarnation. Khushbu Solanki, who has challenged existing legislation in the US, argues that the First Amendment, which protects the rights of Americans to freely practice their religion, could allow the construction of a traditional Zoroastrian Tower of Silence, where bodies are consumed by vultures.

America’s 11,000 Zoroastrians, whose faith prohibits both burial and cremation, have historically flown bodies overseas for internment at one of the few such Towers, or else grappled with thorny legal and religious questions to decide on an appropriate funeral in the US.

“I'm obviously not advocating for any sort of practice similar to this to be conducted in a residential or industrial area,” says Solanki. “But if it's zoned appropriately, and it's safe for whatever animal would be doing the defleshing of the bodies, I don't see a reason as to why it couldn't be allowed, especially given that very similar practices occur on body farms in the US already.”

Become compost

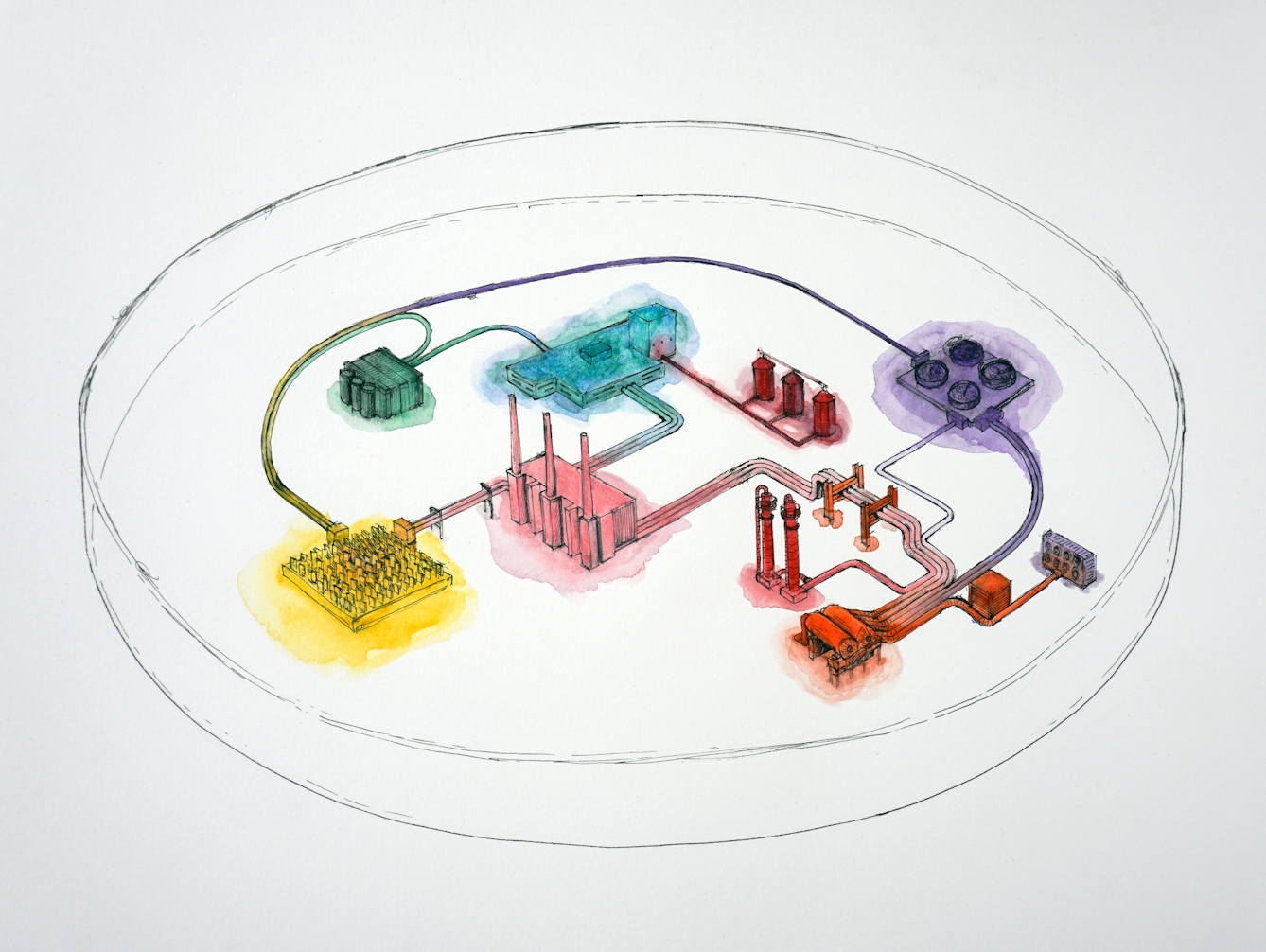

Creatures far smaller than scavengers can also return our bodies to nature. After Washington became the first US state to legalise “human composting”, a start-up called Recompose began building a facility that will open in 2021, where a corpse will be covered with wood chips and aerated to allow microbes to reduce it to soil in around 30 days.

Anna Swenson, Recompose’s communications manager, says people who have signed up for composting have already made big plans for the two wheelbarrows of earth that they will become.

“DeathLab was firstly driven by concern over land use: in New York, graveyards cover five times the area of Central Park, and all major cities face difficult decisions over how best to use scarce space.”

“One of our long-time supporters plans to have her family spread her soil around a beloved tree in her front yard where her grandkids play… I've heard of folks who plan to spread their soil on family land or on a favourite hiking trail.”

For those without a specific tree or landscape in mind, the firm has partnered with a conservation forest in Bells Mountain, Washington, where human-derived soil will be used to restore land from improper logging to its former state as a temperate rainforest. “It’s a beautiful place, and one we're hopeful will allow families to access peace of mind as well as meaningful use.”

Become light

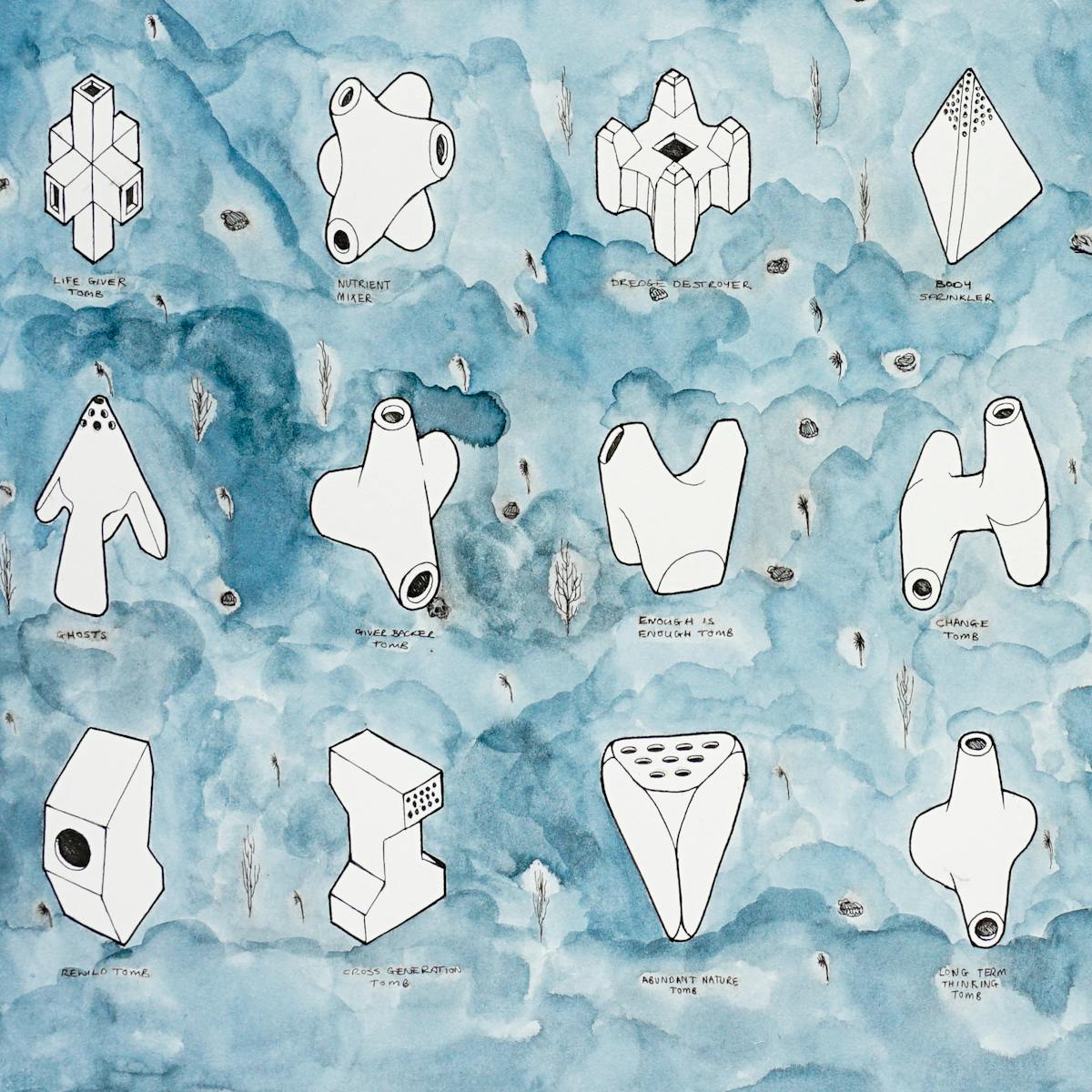

More eco-friendly burials can have other benefits too. For seven years, Columbia University’s DeathLab, led by architect Karla Rothstein, has compared forms of eco-burial. DeathLab was firstly driven by concern over land use: in New York, graveyards cover five times the area of Central Park, and all major cities face difficult decisions over how best to use scarce space. But DeathLab also considers environmental effects.

Rothstein’s team has tested putative eco-burials, including “promession” – which involves freezing the body to -196˚C and vibrating it with ultrasonic waves into a fine dust – and a form of anaerobic digestion known as bio-methanisation. One ready-made substitute for cremation is alkaline hydrolysis, which involves effectively dissolving tissue in strong alkaline liquid that generates one-quarter of the carbon emissions of cremation and consumes an eighth of the energy.

DeathLab’s own answer, Constellation Park, proposes a series of biopods suspended under the Manhattan Bridge as a visible monument, twinkling above the heads of New Yorkers while minimising land use. There, bodies would break down in a zero-emission microbial process, while emitting light powered by the decomposing body within.

The process aims to create an elegant new way of expressing the process of death and natural decay, said Rothstein, “Our bodies are primarily composed of some of the most common elements found in nature (oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium and phosphorus) and after death, these remains can contribute to ongoing natural ecologies.”

“Where the body is interred in a simple shroud without chemical preservation or headstone it could pay for a quarter of an acre of deforested land to be bought up and reforested.”

Become a forest

Australia’s giant landmass has, on average, three people per square kilometre, making it among the most sparsely populated countries on earth. But the country’s vast deforested landscapes and natural habitats have conservation needs highlighted by the recent wildfires, which tore through millions of acres of vulnerable ecosystems supporting koalas, kangaroos, wallabies and birds, killing an estimated one billion animals.

In 2021, Earth Funerals and biodiversity charity Odonata are launching a scheme to run natural burial grounds. Experienced funeral director Kevin Hartley explains that each funeral – where the body is interred in a simple shroud without chemical preservation or headstone – could pay for a quarter of an acre of deforested land to be bought up and reforested. This land can then support captive breeding programmes for the endangered eastern barred bandicoot (a rabbit-sized marsupial) and brush-tailed rock wallaby.

The system aims for new, optimistic rituals of death where relatives of the deceased come together for seasonal planting days, to communally lay down the seeds of the landscape's rehabilitation, says Hartley. “Really, what drives it is this idea that you could make a contribution back to the earth as your last act.”

- This article was produced as part of ‘The Manuals’, an open-source handbook of tools to rebuild our connection with the planet.

About the contributors

Matthew Ponsford

Matthew Ponsford is a journalist who has written for the Financial Times Weekend, the Guardian, the BBC, CNN International and Reuters. He mainly writes about cities, housing, architecture and the environment. He has written ‘The Manuals’, a handbook of tools to save the planet, with artist Andy Merritt.

Andy Merritt

Andy Merritt is one half of the practice Something & Son. They explore social and environmental issues via everyday scenarios, criss-crossing the boundaries between the visual arts, architecture and activism through permanent installations, functional sculptures and public performances. Their work has also been widely exhibited, including at Tate Britain, Artangel, Kinsale Arts Festival, Ireland, Istanbul Biennial, Milan Design Week, and Gwangju Biennale, South Korea.