Virtual reality is not just for gamers: it can take us inside closed museums and galleries, or allow us to explore historical sites that have deteriorated past repair. Marina Gerner considers the power of VR for the armchair culture vulture.

If you think about virtual reality, what is the first image that comes to mind? It’s probably a gamer in a chunky headset aiming at something only they can see.

Virtual reality (VR) is “a set of images and sounds, produced by a computer, that seem to represent a place or a situation that a person can take part in”, according to the Cambridge Dictionary. It doesn’t necessarily involve a headset. Unlike augmented reality, where, say, a virtual lion is projected onto a real meadow, all of what you see in VR is made of pixels.

About five years ago there was a hype around virtual reality, as companies like Facebook, Amazon and Google were vying to bring it to a mass market, but the uptake has been slow. This year the rise of the coronavirus and resulting risk of infection has meant that thousands of museums and cultural institutions had to temporarily close their doors. Could this be the technology’s moment to shine?

Not only does VR allow us to go to places we can’t reach, it enables us to see places we have lost.

Anybody can virtually step inside the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. As you walk across its sunlit wooden floors, you’ll see a vibrant collection of butterflies, laughing faces on Pre-Columbian jars, and floor-to-ceiling windows that reveal palm trees and the hazy city beyond.

Temple of Bel, Palmyra, Syria.

It would, of course, be more impressive to fly out to Rio. But the museum was ravaged by a major fire in 2018 – reducing most of its 20 million artefacts to ash – and a virtual tour is the only way for us to see what it once was. Not only does VR allow us to go to places we can’t reach, it enables us to see places we have lost.

Bringing the past to life

For two millennia, visitors to the Temple of Bel in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra would remark on its unusual mixture of Arab and Greek cultural influences. It looked like a Greek temple, rising from the middle of a walled rectangular court with Corinthian columns; its roof was decorated with stone triangles, like teeth in a crocodile’s jaw.

This magnificent temple’s ruins were considered among the best-preserved of the region before they were destroyed by Islamic State terrorists in 2015, who murdered the archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad for refusing to reveal where valuable artefacts had been moved for safekeeping.

Since then, multiple projects have sprung up to preserve Palmyra through VR. One day the photographic evidence that has been gathered through these projects may well help architects plan its restoration.

While VR that requires headsets is more likely to appeal to digital natives, walking through the National Museum of Brazil is as easy as navigating Google Street View, and the reconstruction projects of Palmyra are similar to a film. But it’s not just re-creations of past glories people can enjoy: there are also representations of places that do still exist.

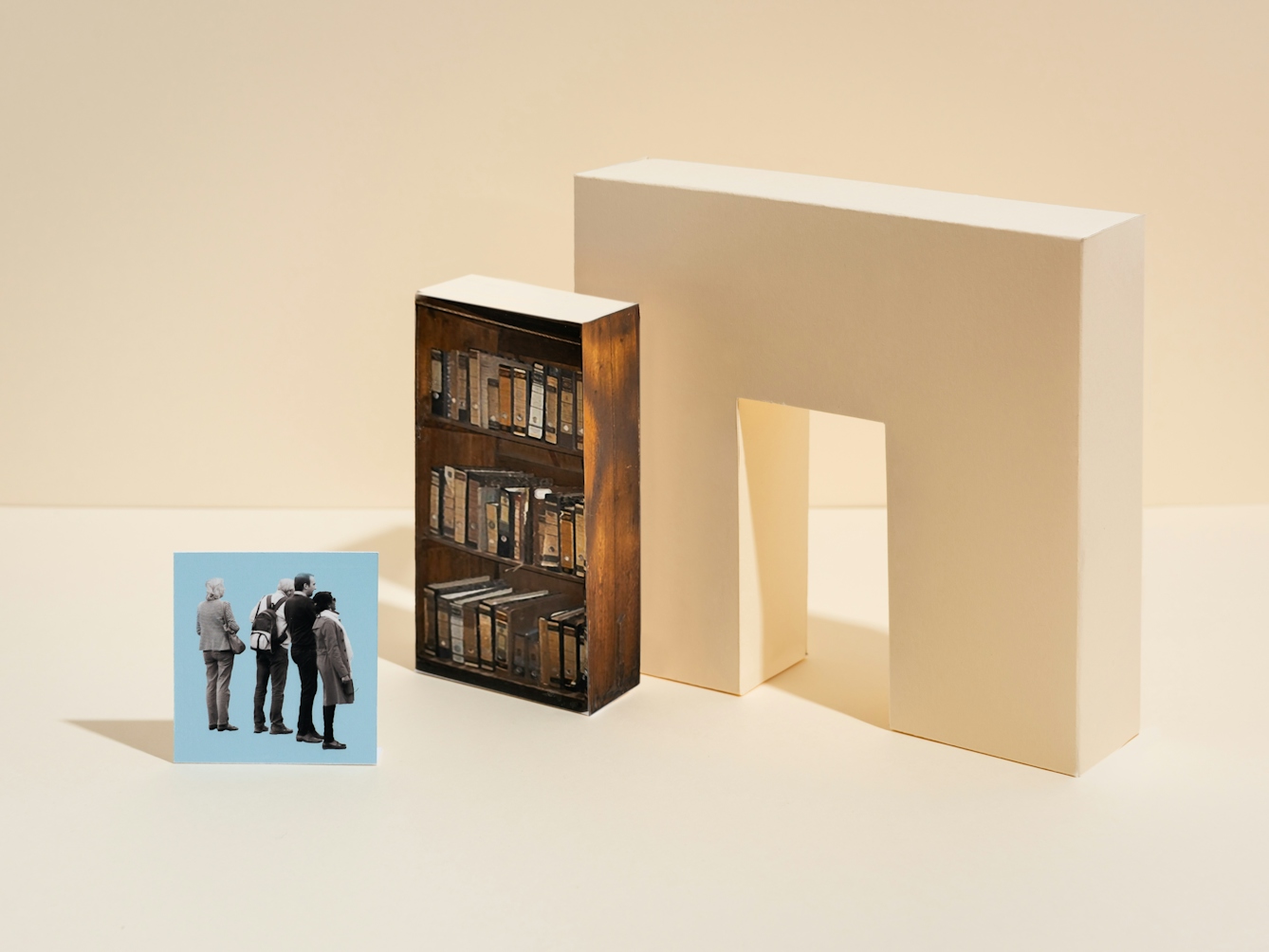

Bookcase and concealed entrance at the Anne Frank House, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Any visitor to Amsterdam will know that tickets for the Anne Frank House are hard to come by, needing to be bought months in advance. Now an app allows you to visit the house virtually and wander the rooms of the Secret Annex, where Anne, her family and their friends tried to hide from persecution during the Holocaust.

But can VR ever replace the powerful words of Anne Frank’s own diary? Of course, it can’t – and, wisely, this app doesn’t try to do that; instead it intersperses the tour of the house with Anne’s words. For anyone who has read the diary but hasn’t visited the house, this is the next best option. Yet it’s still Anne’s narrative rather than the pixels that draw you in.

Telling stories and preserving places

Representing a house in VR is also very different from representing people virtually. In 2016 the BBC used VR to chronicle the story of Maria, a single mother, who is trafficked from Nicaragua to Mexico and forced into sex work.

The intention of this 11-minute-long VR documentary was, presumably, to create empathy – but the result can only be described as bizarre, at best. Maria’s first-person narrative is powerful; however, the cartoonish brothel-keeper does nothing to reinforce the seriousness of the situation. Neither do the Sims-like sex workers soliciting men on the street.

There is a fine line between creating empathy and ‘gamification’. And no amount of virtual reality can convey Maria’s journey without trivialising it. VR just isn’t the right medium for this message.

Roman Fresco, Villa dei Misteri, Pompeii, Italy.

Ethical questions should never be ignored by VR creators. They need to consider who and what to show, the role of the viewer, and the relationship between the two. As a journalist and a scholar, I always analyse the choices that have gone into conveying a story: what is evoked through words, what can be seen and what can be heard.

So far, most VR projects rely heavily on one of our senses: sight. This can have a vertiginous effect on the viewer, causing motion sickness. In essence, VR promises to expand two dimensions into three. Rather than seeing what’s directly in front of us, we can look to the sides and around us. And when it’s well done, that can make the experience more immersive than 2D. For example, a virtual tour of frescoes at the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii from 80 CE – where the front wall as well as both walls to your sides are painted with large-scale figures engaged in the ritual of a cult – feels deeply engaging to me.

Reality and the imagination

Outside of the TV series ‘Black Mirror’, it’s hard to imagine a time when VR can compete with reality. For me, Stonehenge from afar is always better than Stonehenge in VR. Seeing it with my own eyes, luminous against the open sky, gives me a sense of its magnetic appeal throughout the ages.

VR is most powerful when it allows us to travel to places we can’t go. It can be a tool for preserving our cultural heritage, and especially the memory of what has been lost. But some things are better left to the imagination and our mind’s eye.

About the contributors

Marina Gerner

Marina Gerner is an award-winning feature writer published in The Times’ Raconteur, the Guardian, WSJ and co. In a true Renaissance manner, she prefers to cover a range of topics from culture, business and tech to having a single niche. Born in Kiev, her family moved to Frankfurt as political refugees, before she moved to London – which explains why she has a PhD on cosmopolitanism. When she’s not writing, she gives lectures on digital journalism and visual culture at Birkbeck University.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.