WhatsApp chat groups are fertile soil for misinformation to spread among older adults, which is particularly damaging during a pandemic. Rianna Walcott finds out how best to counter fearmongering advice.

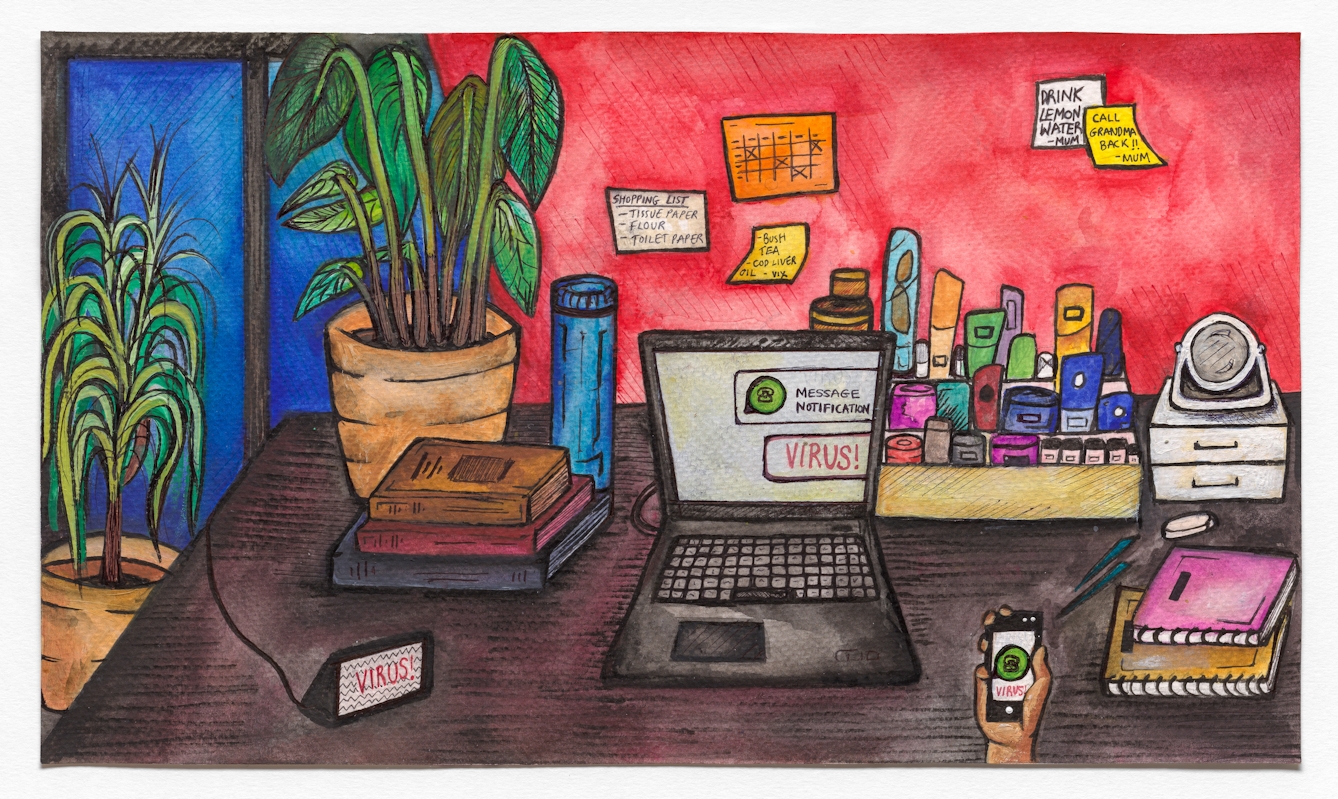

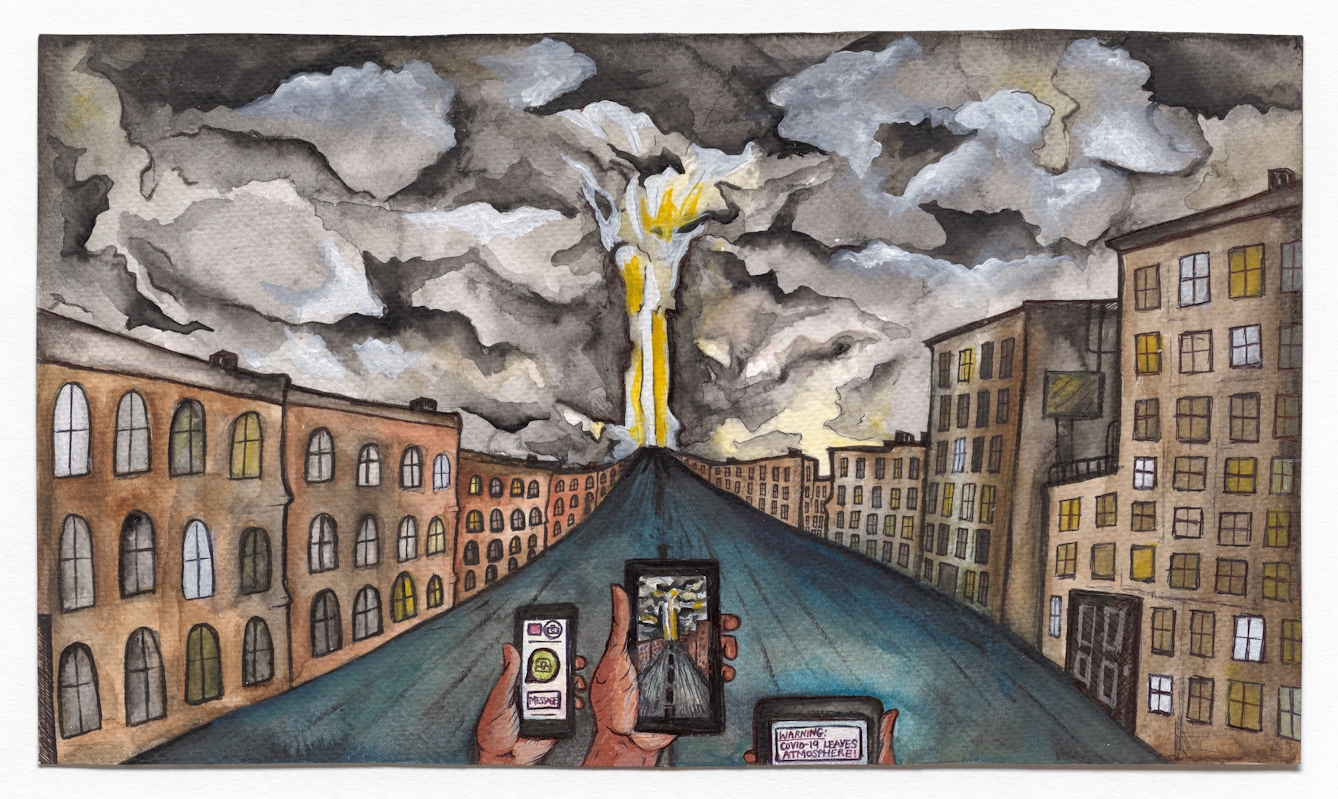

Chain mail in its many forms is a burden that is inextricably linked to social networking systems. If you use WhatsApp’s messaging service, then no doubt you will have received some iteration of these viral messages, asking you to do anything from participate in a mass prayer to make COVID-19 go away to turning off your phone at midnight due to increased radiation in the atmosphere.

If you happen to be Black, you might even have a few repeat offenders that you affectionately (or wearily) refer to as “WhatsApp aunties”. In the wake of rising panic surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, I noticed with exasperation an exponential increase in the frequency and number of these fearmongering hoaxes, even from family members I had once considered level-headed.

After a few weeks of persistently debunking these messages, to varying reception, I began interviewing a number of other Black people who were combating misinformation within their own families. I wanted to see if there was a more effective way to help those in my family who did not grow up with the internet recognise “fake news”.

Our generation tend to be more critical of media and are more likely to question information sources. “I know when I see a thread, I won’t just take it at face value; I always go to the comments to see what other people are saying about it first. But [WhatsApp aunties] haven’t adapted to this, and there isn’t enough training or information for older people on how to fact-check.”*

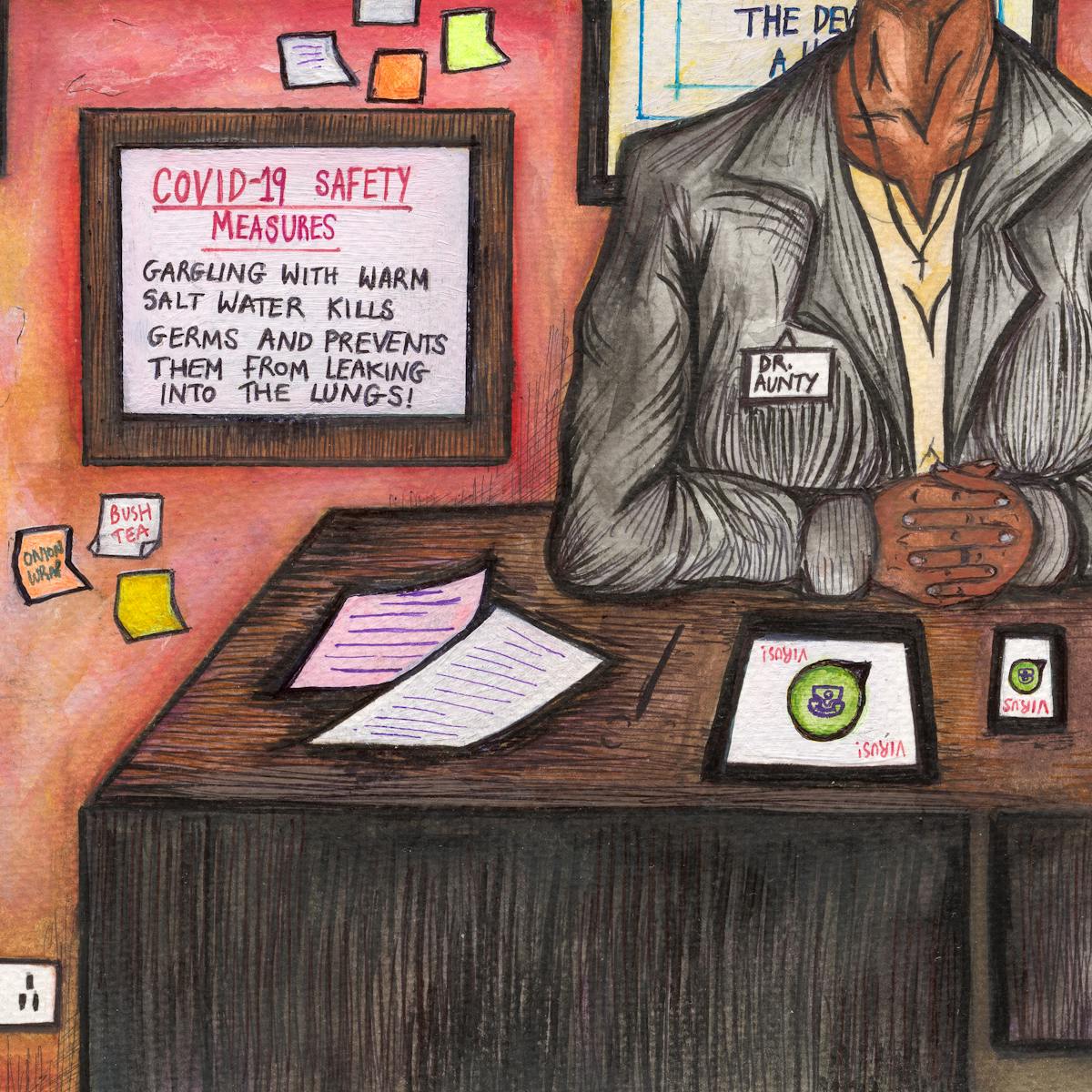

How fake advice can look convincing

Many of the chain messages in circulation have features in common that make them especially likely to go viral. There is an illusion of proximity to authority in most of the long text images – “I received this information from X who works at Y” is a common feature, as though carefully kept insider knowledge is being siphoned off and passed through Black networks.

The doctor’s advice always comes from a foreign doctor – Japanese or maybe Taiwanese: this Asian stereotyping lends credibility, while also being distant and vague enough to not be verifiable.

“I noticed with exasperation an exponential increase in the frequency and number of these fearmongering hoaxes, even from family members I had once considered level-headed.”

The advice is simple, natural, holistic, homeopathic: eat lemons because they are ‘alkaline’ and kill the pathogens, swill hot water because it will wash the virus away from the lungs and into the stomach, make a poultice out of onions and strap it to your chest with banana leaves. The resurgence of bush tea, compresses, poultices and other African and Caribbean home remedies is comforting in this uncertain time.

Many chain messages debunked in previous years are having a resurgence. They can be edited to make them relevant to new catastrophes and recycled between disasters with only superficial tweaks. In order to refresh the content, they are often run through a text-to-speech program and forwarded as a voice note or read on video by a ‘credible’ source.

The fake sources are particularly alarming, as illegitimate advice is dressed up with a legitimate-looking background, or passed off as being from a recognised source like WHO or UNICEF.

Who are WhatsApp aunties?

The aunty thrives on WhatsApp in particular for a number of reasons. In comparison to digital aficionados, who get their news from a multitude of sources on social media and traditional mass media, our elders have an ecosystem of information that is person-centred. A symptom of their general distrust of mainstream media, which is understandably based in histories of anti-Blackness in institutions like medicine, media and policing, means they then overcompensate, leaving themselves vulnerable to more disinformation.

Esther Oluga writes for Black Ballad on this phenomenon, noting that the hostile environment in the UK – from consistent anti-migrant sentiment, to specifically anti-Black government treatment of Windrush migrants – leaves our elders with an understandable distrust of government messaging, and a reluctance to use targeted government initiatives such as the government-led WhatsApp collaboration, a coronavirus information service.

WhatsApp is a natural breeding ground for hoax messages. The platform offers end-to-end encryption, so forwarded messages can’t be traced back to their source – this security is a reason why many people originally started using WhatsApp. Many of the people I interviewed also noted the connection WhatsApp provides, as the “main way to communicate with friends and family abroad in the diaspora. Back in the day we had to buy phonecards, but WhatsApp provides easy access.”

“The advice is simple: eat lemons because they are ‘alkaline’, swill hot water because it will wash the virus away, make a poultice out of onions and strap it to your chest with banana leaves.”

Researcher and podcaster Surer Mohamed notes in our interview that “every Somali woman over a certain age has at least two apps on their phone, the Qu‘ran and WhatsApp. It makes conversation and connection possible, particularly in communities where orality is central to the culture. One of the worst insults in our community is to be ‘someone who doesn’t answer the phone’.

“The concept of a ‘WhatsApp aunty’ brings to mind the people who use WhatsApp as their central social media space. For me it’s one of many apps – I have Instagram, Twitter, Facebook; I have all these other places to nest parts of my identity. But aunties have a different relationship to the internet. There’s a simplicity to it – it’s a platform rather than a network.

“Aunties come from communities where they are the networkers: they are where you find out, ‘Oh, that person dropped out of school,’ or who is getting married. They don’t need Facebook to tell them what is going on with so and so’s daughter – they know! Ring aunty to find out.”

In this ecosystem of knowledge, where the aunties themselves form the network, it’s no wonder the term “WhatsApp aunties” is so heavily racialised and gendered. The similarities to community gossip remind interviewee Lola Oriowo of “the same sort of stuff you’d hear from aunties in church. It’s an evolution of the same silliness I used to laugh at as a 13-year-old.”

Suspicion as a rational response to mainstream messages

With the specific – and well-founded – distrust Black communities have towards Western institutions and public bodies, it’s no wonder we turn to indigenous and traditional knowledge when faced with a crisis like COVID-19. Lola referenced this in relation to the Nigerian community, who “know that the government is corrupt, so it makes sense that people would feel like medical secrets were being hidden from them for profit, and that mirrors what’s happening with the British public, and the same distrust of British institutions”.

Similarly, an awareness that Black doctors, nurses and patients in the UK are dying disproportionately when it comes to the pandemic, as well as suggestions from French medical practitioners to test COVID-19 vaccines on the African continent, only fuels the concern Black people have about their welfare and safety at this time. These hoax messages are hinged on our real and valid fears of anti-Blackness, and stranger things have happened than non-consensual medical experimentation on Black people.

Responding to these kinds of messages in your family group chats is a delicate operation. “Before the crisis I would just say ‘thank you’ for all of them and ignore them. When you receive them, they don’t really need you to respond or take note of it,” Lola tells me. “They just send them.

“Warning: COVID-19 leaves atmosphere!”

“Now I’m more likely to debunk the messages, respond and tell them they don’t make sense, or refer them to the actual news, especially with people who didn’t send them before the pandemic. Over the last week I’ve been contributing alternative, more factual sources to the chats. So I’m getting a bit aunty WhatsApp myself.

“I’ve been sending round a ‘coronavirus syllabus’ that someone has put together: a bunch of articles, podcasts and videos.”

Surer adds that understanding how Black elders will respond to your well-intentioned advice is critical. “Whatever big degree I may get, I’m a woman, and I’m young, and I can’t speak with authority in that space. You can’t imply you know more than those older than you or it’s, ‘Do you know I could birth you?’ ‘Yes, aunty, I know. You knew more than me before I was even born…’

“There are different ways of handling it, like some people link to an article debunking the message” – at this point I nervously admit I do this – “but do you really think aunty, sitting on her couch, is going to go, ‘Oh well, Snopes said this isn’t right, okay’? That’s not going to happen! I find it more helpful to use people they already respect to make your point, like finding information that is contextualised in a way they’ll be interested in.”

Practical steps to halt disinformation

Professor Tiffany Li, a legal scholar of technology and policy, articulates the bizarre role many of us have taken on during this crisis, and offers methods of effectively and gently pointing out disinformation, including the SIFT method (Stop. Investigate the source. Find better coverage. Trace claims, quotes and media to the original context), and three steps for talking to loved ones: 1) evaluating if it’s worth engaging, 2) not patronising; creating a dialogue rather than a lecture and 3) offering to trade information and sources.

Beyond the individual battles many of us are engaged in, WhatsApp has taken steps to reduce message forwarding. As the messages are end-to-end encrypted, it isn’t possible to analyse or fact-check their content, so under the new changes, once a single message has been forwarded more than five times, users will only be able to forward it on to a single chat at a time rather than five at once. This will slow the rapid forwarding of chain messages and hopefully encourage users to think more carefully about what they send onwards.

Improved digital literacy, particularly in times of heightened online presence and globalised anxiety during a pandemic, is critical for physical and emotional wellbeing. This holds true for both the anxieties of Black elders, and the anxieties of their children who are trying to keep them safe.

* Some interviewees chose to remain anonymous.

About the contributors

Rianna Walcott

Rianna Walcott is a PhD student at King’s College London, researching Black women’s identity formation in digital spaces. She co-founded projectmyopia.com, a website that promotes inclusivity in academia and a decolonised curriculum. She has written about feminism, mental health, race and literature for a variety of publications, alongside co-editing an anthology, ‘The Colour of Madness’, about BAME mental health.

Maïa Walcott

Maïa is a Social Anthropology undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh and a multidisciplinary artist working with sculpture, painting, illustration and photography. Her work has been widely published and exhibited, appearing in the anthology ‘The Colour of Madness’ and as part of ‘Project Myopia’. Maïa was also the in-house illustrator for the literary magazine The Selkie, and photographer for photo exhibitions such as ‘The I'm Tired Project’ and ‘Celestial Bodies’.