Charmaine was sexually exploited as a child in the care system, and as a result experienced abusive relationships, addiction and the world of sex work. But the horrible things that have happened to her don’t make her a bad person, as she reveals in her honest and poignant story.

Surviving sex work on the streets

Words by Charmaineartwork by Jessa Fairbrotheraverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

I was four when I was first taken into care. I was being sexually abused by my stepdad and my mum was an alcoholic. No one explained what was happening. Suddenly I was in a big house with lots of other kids and I didn’t know where my family had gone. I remember thinking I must have done something wrong. The staff used to say that it wasn’t my fault, but they wouldn’t tell me why I couldn’t go home. We never spoke about the sexual abuse.

I was nine when I first sold sex.* One of the older girls at the children’s home in Leeds was already working down on Spencer Place in Chapeltown. She was 16. We wanted money to buy drink, so we got dressed up, went down on the beat, and a punter pulled up. I thought I was doing something normal. I thought sex was normal. To me, it was. I was amazed that anyone would pay me for it. I remember feeling excited about how much money I was holding.

[*This is rightly recognised as child sexual exploitation today. The author wished to fully communicate how she understood what was happening to her at the time, but it is equally as important to state that no child can ‘sell sex’.]

I was 11 when first took crack and heroin. I used to lie about my age all the time, but people must have known. I fell in with drug dealers pretty quickly, but to me they were my friends. I didn’t know I was being coerced. By 12, I had a dealer boyfriend. He took me off the streets for a while, but he also got me hooked on drugs. He used to beat me up and tell me it was to make me stronger. I’ve had beatings all my life.

I was 16 when I was first arrested for soliciting for sex. Today there are support groups and outreach programmes to help working girls, but there was none of that when I was on the street. The police would arrest you, slap an anti-social behaviour order on you, and issue a fine. Then you’d have to go back on the streets to earn the money to pay the fine.

Once you’ve got a police record for soliciting, you can’t get a regular job. Once you’ve got a smack habit, people just look away.

"It sounds bizarre, but I loved being in jail. It helped me. I got counselling there and was detoxed. I’ve never been to school and there were education programmes in prison."

Going to jail and getting clean

I was 17 when I first went to jail. I got eight years for kidnapping and firearms offences. During admission, I found out I was six and a half months pregnant. I gave birth to my daughter while I was serving time at New Hall Young Offender Institute in Wakefield.

I know people looked down on me when I was on the street. But they didn’t know anything about me.

It sounds bizarre, but I loved being in jail. It helped me. I got counselling there and was detoxed. I’ve never been to school and there were education programmes in prison. There was a structure that I’d never had before. They showed me how to do really simple things like filling out forms, opening a bank account, and doing laundry. I was like a baby learning to walk for the first time.

I was in and out of prison for ten years. At one point it was my second home. But it was better than being out on the streets. It was better than being on drugs.

I first got properly clean at 28. My mum had got in contact with me while I was in jail and I went to stay with her when I was released. Being with my family again centred me. After years of not knowing where I was going to sleep or eat next, I had a proper home. I was put on a methadone script and got off smack. Local support groups helped me exit sex work as well.

I got my first job at 34. I was put in touch with a charity that helps people with a criminal record find work. They all knew I’d been in jail, but I didn’t dare tell anyone why. I thought if they knew I’d been a drug addict and worked on the streets as a prostitute, they would judge me and look down on me. I got a job in a department store and I was good at it, but then someone I’d been in jail with recognised me and all my past came out. When they fired me, they said it was because I hadn’t disclosed my full record during interview.

"One of the hardest things about getting clean is cutting ties with your past life."

Relapsing, recovering and family life

I relapsed shortly after that. One of the hardest things about getting clean is cutting ties with your past life. Giving up drugs is easy compared to trying to get someone to give you a job when you’ve got a criminal record. I’d been a junkie and a working girl for twenty years. That was all I knew. I was so upset I’d lost that job that I started using again. Just a bit, I thought. Just to help me through this. But it doesn’t work like that.

I started dating a drug dealer and everything spiralled very quickly. I was soon back on heroin and working on the street to feed my habit. I was so ashamed I left my mum’s and cut all contact with my family. I can’t be around them when I’m using.

I worked in the Leeds managed area then and things were very different. The police don’t arrest punters or the girls there. They try to help you instead of sticking you in a cell. There are also charities like Basis to support women like me. They helped me get off drugs again, move back with my mum, and to make better choices. They’re still supporting me now.

I was 36 when I became a grandma for the first time. My little girl has a family of her own and I want to be there for them. I’m 38 now and am clean, sober and no longer do sex work. But it’s not easy. My record makes it difficult to get a job, I am a full-time carer for my mum, and I’m on Universal Credit. I’ve had my benefits sanctioned several times because of administration issues, and I know I could go down on the beat anytime and earn several hundred pounds.

Sometimes I can’t believe I survived what I have been through. I should have died so many times, but here I am. Society writes us off as ‘prostitutes’ and I know people looked down on me when I was on the street. But they didn’t know anything about me. What people don’t seem to understand is that this is our lives. People live this. I know horrible things have happened to me, but I’m not a horrible person. Working girls are not horrible people. We’re all just trying to get by.

About the contributors

Charmaine

Charmaine (not her real name) is a recovering drug addict and sold sex on the streets of Leeds for 25 years. She has now exited sex work and volunteers with Basis, a sex work project in Leeds to support other women.

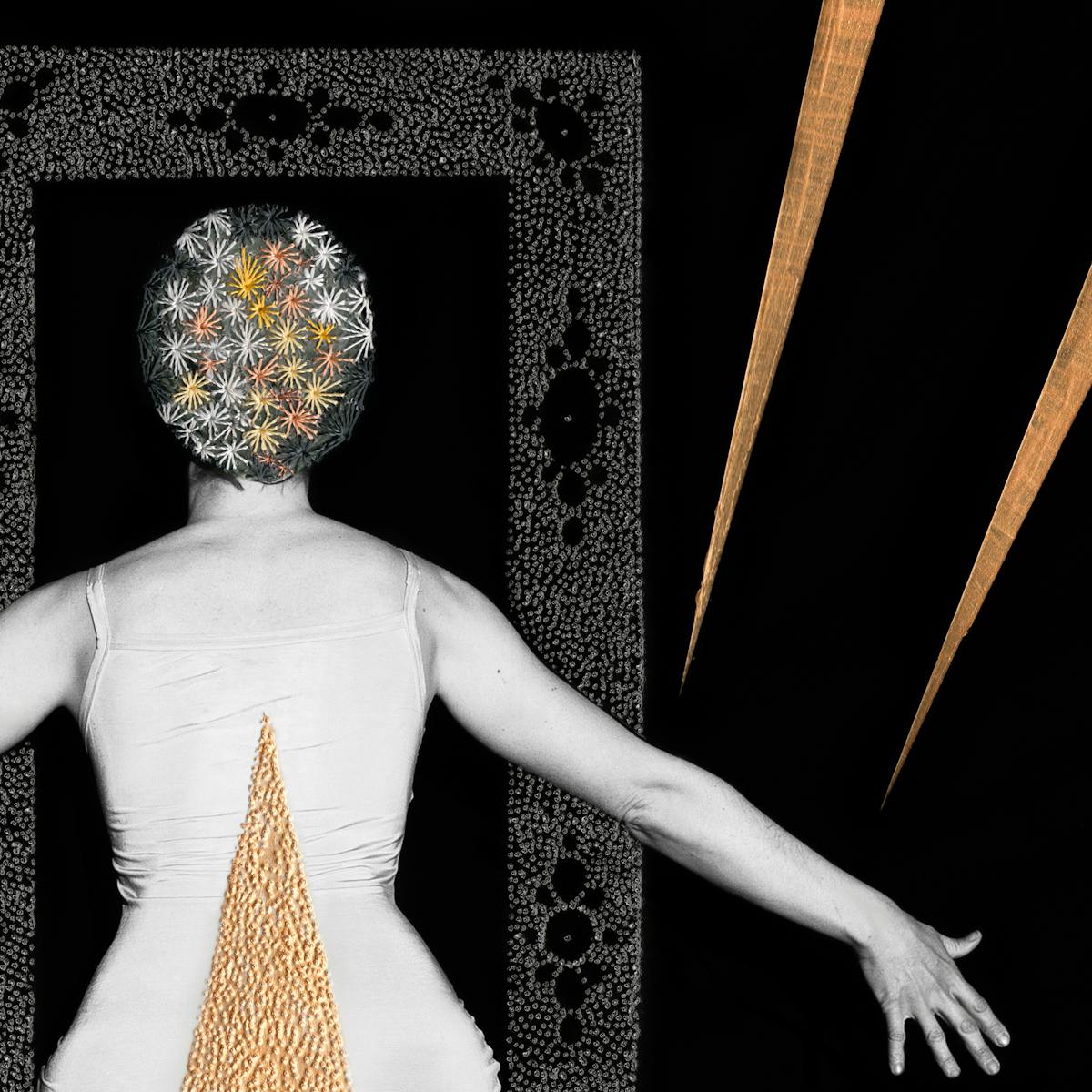

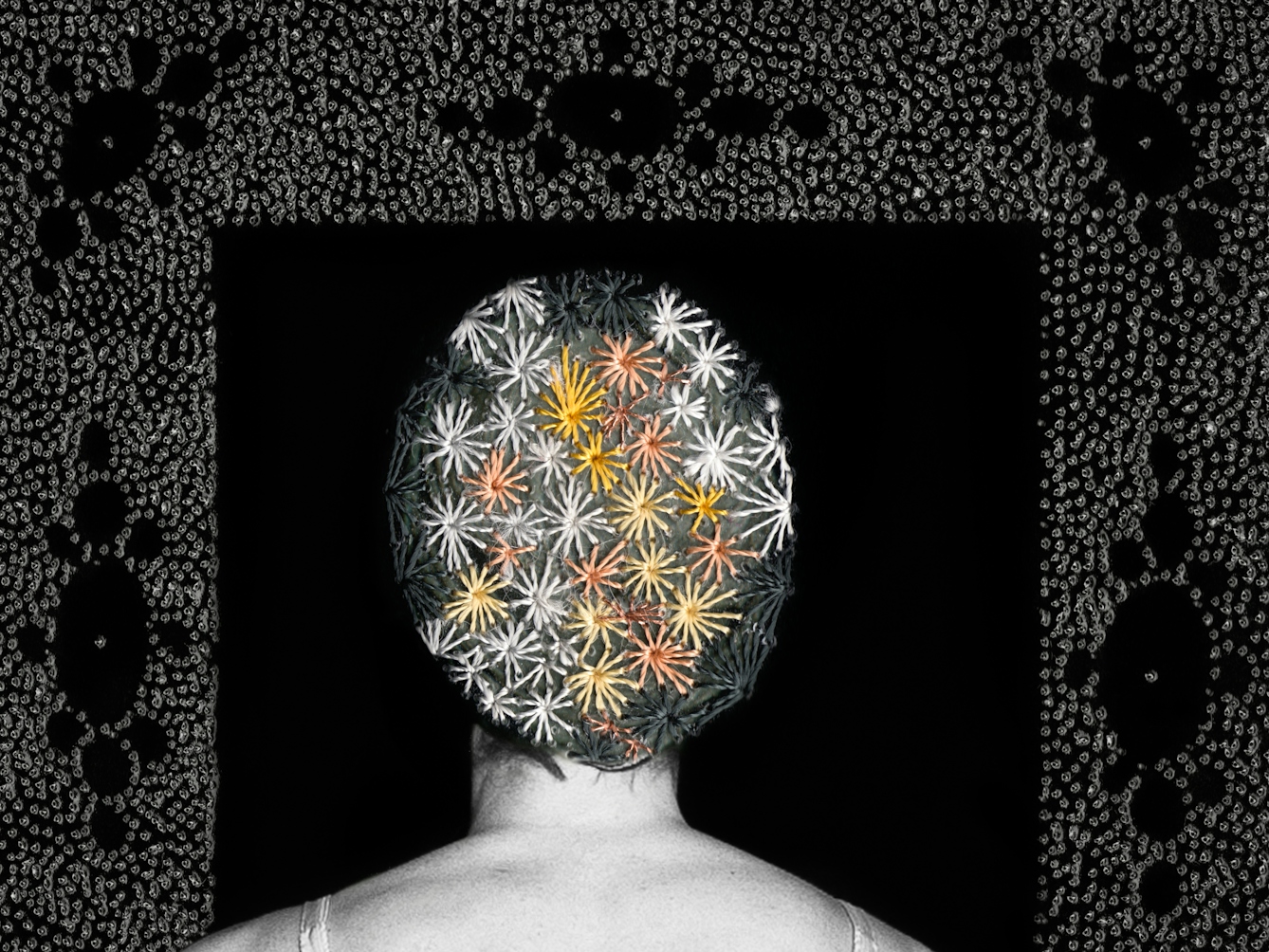

Jessa Fairbrother

Jessa Fairbrother is a visual artist using photography, performance and stitch. Her long-term investigations revolve around subjects of yearning and the porous body. Her work is held in numerous private and public collections worldwide, including Tate Britain, the V&A, the Yale Center for British Art and the Museum of Fine Art, Houston. Her work is represented by the Photographers’ Gallery, London and AnzenbergerGallery, Vienna. She is also a QEST (Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust) scholar.