This short story recounts the journey of ‘Wellcome Trust’ after their first episode of mental illness. Faced with inadequate healthcare and an impenetrable benefits system, their life spirals downwards. The character’s story is drawn from the real-life experiences of Recovery in the Bin members.

Happy Joy Smile

Words by Recovery in the Binartwork by Olivia Twistaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

Wellcome Trust sat in the shiny new waiting room of the Recovery College and surveyed a rack of leaflets and the day’s latest Metro newspaper (headline ’75 Per Cent of Welfare Claimants Are Faking Their Illness’) left on the coffee table.

They were early. As they selected a glossy brochure about wellness and exercise courses, Wellcome’s mind wandered back through the sequence of events that had led to them being here, trying to pinpoint when circumstances became an overwhelming engine of descent. At the same time, a voice in their head, resembling a previous CBT therapist, criticised this disempowered thinking.

What was the moment it became inevitable? Wellcome had been a good citizen, working, renting a flat, moderate use of alcohol and other drugs, and in a steady relationship. But then it didn’t work any more. Holidays, buying things, work, clubs, plans for the future: Wellcome was not keeping up, and after a weekend break went disastrously wrong, they went to their GP.

After a three-week wait, they had their GP appointment. They explained to the doctor: “Something’s wrong with me: I am unhappy in being alive, my thoughts bother me and intrude in weird ways, and I want to hide from the world and myself.” The GP handed them a leaflet and said to make another appointment if they wanted to explore seeing the mental health team.

Wellcome asked how soon could it this happen. “Oh, within three months,” the GP said cheerfully. The receptionist, when queried, was more pessimistic: “Six months.”

Wellcome’s mind was not obedient to the current waiting times of austerity’s discipline. Two weeks later, they found themselves being delivered to an A&E department at 3am by weary police. Muddy, bloody, and desiring of it all to end. To silence their head.

After spending nine days on a ward, receiving a team formulation in which Wellcome had no input, they were discharged.

In and out of hospital

It was at this point the world needed to stand back, give Wellcome space and not demand anything. But… work found a way to fire them after sick leave. Phone advice from a company called Maximus on how to remain in work proved not up to the task of controlling their mind. Wellcome’s partner decided they had not signed up for caring for someone in mental distress. The savings Wellcome had built up were now steadily ticking down as rent, food and bills ate away at them.

The community mental health team were a nebulous presence somewhere, sometimes at the end of a phone line. Wellcome would not burden them with their problems unless absolutely necessary. But when they did, the team failed to appreciate that their desperation would not be cured by a cup of tea and a hot bath.

Wellcome’s latent self-harm had amped up. At the hospital, they found that staff visibly judged them for “wasting our time”. Someone decided to staple up Wellcome’s wounds without anaesthetics to teach them a lesson.

Their desperation would not be cured by a cup of tea and a hot bath.

One week later, Wellcome was begrudgingly admitted to a ward with both infected wounds and a complete collapse of mental state. They contemplated the black mould in the shower and the crying of a fellow patient who had been re-diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and was being mostly ignored ahead of early discharge (apart from a Brexit-celebrating nurse commenting, “Should have gone back to your own country”). Wellcome felt the meds fog their brain.

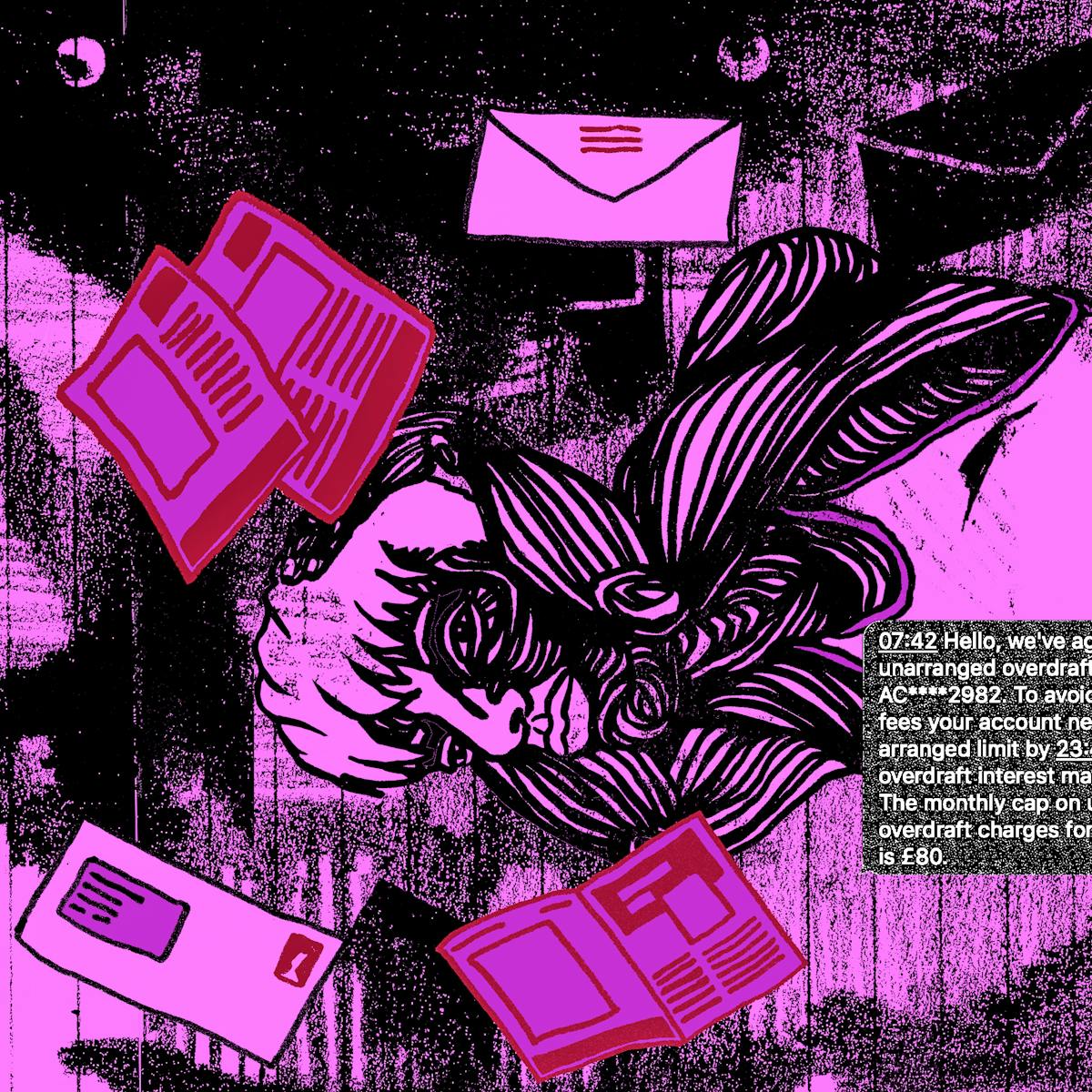

After being discharged three days later, Wellcome bravely opened some of the pile of mail that had accumulated at their flat: overdraft, rent arrears, red bills. Wellcome phoned the mental health team. They said to make a benefits claim.

Going back and forth between the Department for Work and Pensions, Maximus (again), and Atos (which carried out intrusive eligibility assessments) consumed their life. There were forms, hours spent waiting on hold and two crisis-inducing assessments done by a nurse and a physio. Wellcome became consumed by a growing terror of what those brown envelopes would say when they dropped through the letter box.

The result? Their benefits application was turned down. The community mental health team told Wellcome to appeal but gave no help. Chat on the internet was grim: others spoke of waiting over a year for an appeal, the lies told by assessors, and many deaths.

Eventually they got help from a disabled activist group, and an appeal was lodged to review their benefit decision, but the inevitability of eviction approached.

The mental health team had decided to discharge Welcome after six months because they had “failed to engage”. When Wellcome rang for support, the conversations would be brief, ending in “you need take responsibility for your own mental health”. An appointment at the new Recovery College was made on their behalf.

The final straw

At the Recovery College, glossy brochures were given and self-management courses explained. Any questions?

Wellcome said, “I would love to feel better – don’t you think I would if I could? What I need help with now, today, is to not be evicted and to have some money to buy food and pay my electricity. Can you help?”

The adviser thrust some leaflets for overloaded or uninterested advice organisations – which Wellcome had already approached – across the desk, and Wellcome was sent on their way to “think about it”.

Somewhere the fog had messed up the days, because as Wellcome turned on to their road, all their belongings were sitting on the pavement. The eviction had been today. This was a weight too great to bear.

Wellcome turned and walked away. They kept walking, for hours, into the night. As they walked, they noticed the hostile city architecture, the cobbles, lumps, spikes, slopes and armrests that meant there was nowhere to sleep.

It was cold. After more walking, Wellcome eventually found a corner of a small loading dock to rest, took a handful of meds, and fell asleep. When it dropped below freezing, they never stirred. In fact, they never awoke again.

Wellcome’s family had them cremated, and on the same day the CEO of the NHS trust gave one of her famed TED Talk-style presentations on leadership and wellbeing. Thanks to Wellcome’s sacrifice and those of many others like them, the CEO could report an impressive increase in people who were “no longer engaged with services”. An OBE was sure to follow. The metrics were good; there was no end in sight.

For more on the themes covered in this story you can read articles from Recovery in the Bin, National Audit Office information on deaths by suicide of benefit claimants, Disability News Service’s case against the Department for Work and Pensions, the Observer’s report on mental health bed shortages, and the Architectural Digest article on hostile architecture.

About the contributors

Olivia Twist

Olivia Twist is an illustrator, arts facilitator and lecturer from east London with an MA in Visual Communication from the Royal College of Art. The key threads that can be found in her work are place, the mundane and overlooked narratives. Her striking visual language is comprised of a myriad of esoteric layers informed by a propensity for human-centered research methodologies.