As a child, Briar Ripley Page was terrified by a story about a woman who kept a lifelong secret: that her head was held on only by a green ribbon. But strangely, their older self came to find very detailed, subversive tales of ‘body horror’ a source of support, strength and comfort.

When I was in second grade, around Halloween, my teacher gathered the class into a semicircle on the rug at the front of the room and read aloud to us from an illustrated book of scary stories.

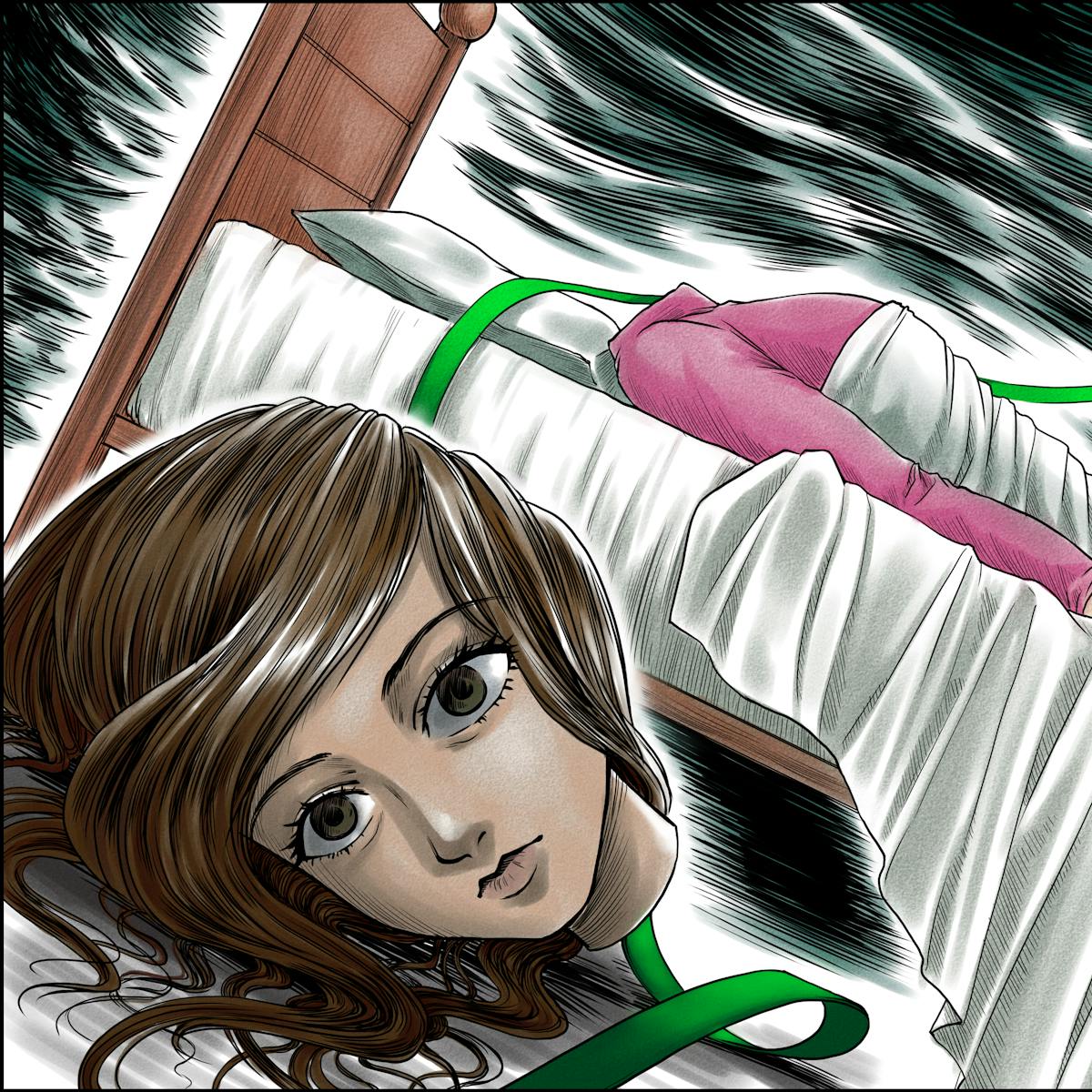

The first story was about Jenny, who always wore a green ribbon tied around her neck. She refused to tell anyone why she wore the ribbon. She also refused to take it off, despite her husband’s many attempts to convince her to do so. At the end of the story, Jenny took ill and died. Her husband finally untied the ribbon around her neck, only to recoil as her head fell off.

I was so upset by the story that I wouldn’t even look at the illustration of Jenny’s head rolling onto the floor. I curled up on the carpet like a woodlouse, covering my eyes and ears. The other kids laughed at me. The teacher was bemused.

I wasn’t able to articulate it at that age, but I understood the deeper meaning of the tale. The horror lay not in the image of Jenny’s head tumbling from her neck as her husband looked on, but in Jenny’s lifelong physical fragility, in her need to keep that fragility a secret lest someone take advantage of it. Even the person who was supposed to love her most in the world couldn’t be trusted to believe what she told him about her body and its needs.

“When I was seven, people didn’t believe me about a lot of things.”

How I became unbelievable

When I was seven, people didn’t believe me about a lot of things. They didn’t believe me when I told them that I could read perfectly well, even though my spelling was atrocious and my handwriting an indecipherable series of hieroglyphs. They didn’t believe me when I told them that the sound of a fire alarm, a balloon popping, or shoes squeaking on linoleum caused me such intense discomfort that I felt nausea and panic.

They didn’t believe me when I told them that sounds had colours. They didn’t believe me when I told them that the reason I fell down so often was that my ankles would bend over underneath me without warning. They didn’t believe me when I told them that I didn’t want to grow up to be a woman, to marry a man and have children.

I had a reputation for fabricating stories and making bizarre excuses to get out of classes or chores.

A little while after my teacher read us the story of Jenny and the green ribbon, I started needing to pee every few minutes, no matter how little I’d had to drink. Urinating was painful, but I couldn’t hold it in. I tried explaining this to my teacher, but instead of sending me to the nurse or calling my parents, she gave me a lecture on whining and malingering. I bore up as best I could for another few weeks of increasing discomfort, until I started peeing blood.

After that came a parade of doctor’s appointments and hospital visits. I got X-rayed. I had strangers examining my body in distressingly intimate ways. The doctors feared I might have a serious disease, maybe even cancer, but they soon realised it was only a bladder infection. Because it had gone on for so long, the infection had spread to my kidneys and I needed intensive treatment with powerful antibiotics.

I was frightened, but I felt a superior thrill of victory, too, when it turned out that there was really something wrong with my body. I had been right. My pain was not meaningless or imaginary.

In a different kind of story, we’d end there. I would have learned a lesson about self-assertion and trusting my feelings. The people around me would have learned a lesson about accepting others, even children, as authorities on their own experiences of embodiment. But this is a true story, and that means it’s a kind of horror story. A scary story for a dark night.

“When I was thirteen, I told my mom that I thought I was bisexual.”

Another diagnosis

Shortly after my bladder/kidney infection, I was diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. That explained my sensory sensitivities, my emotional outbursts, and a lot of my difficulties in school.

The adults in my life were more willing to believe me about some things after that, but not necessarily more willing to accord my differences respect. Maybe I didn’t intend to be melodramatic, but that didn’t mean my emotions weren’t absurd and unwarranted. I still couldn’t be trusted to know myself.

When I was thirteen, I told my mom that I thought I was bisexual. Her response was swift and confident. “No, you’re not,” she said.

She went on to explain, gently, that there was nothing wrong with being gay. She had dear friends who were gay! But, she told me, the vast majority of people were straight. And if someone my age thought that they were not even really gay, but bisexual, they were almost definitely just a confused straight person.

When I felt something I wasn’t supposed to feel, I rebuked myself.

I faltered. By my teens, I had internalised the idea that the people around me knew more about my body, about my feelings, about what I wanted and needed, about what was normal and what wasn’t, than I did or ever would. When I felt something I wasn’t supposed to feel, I rebuked myself.

I ignored my still-floppy ankles and the way one of my shoulders occasionally popped partway out of its socket. I ignored my feelings for girls, and I tried to ignore my increasing discomfort with my body as it grew breasts and hips. I starved myself to stave them off, and to avoid menstruating.

I discovered horror comics.

“But the one that scared and disturbed me the most… was a Japanese manga called ‘Uzumaki’.”

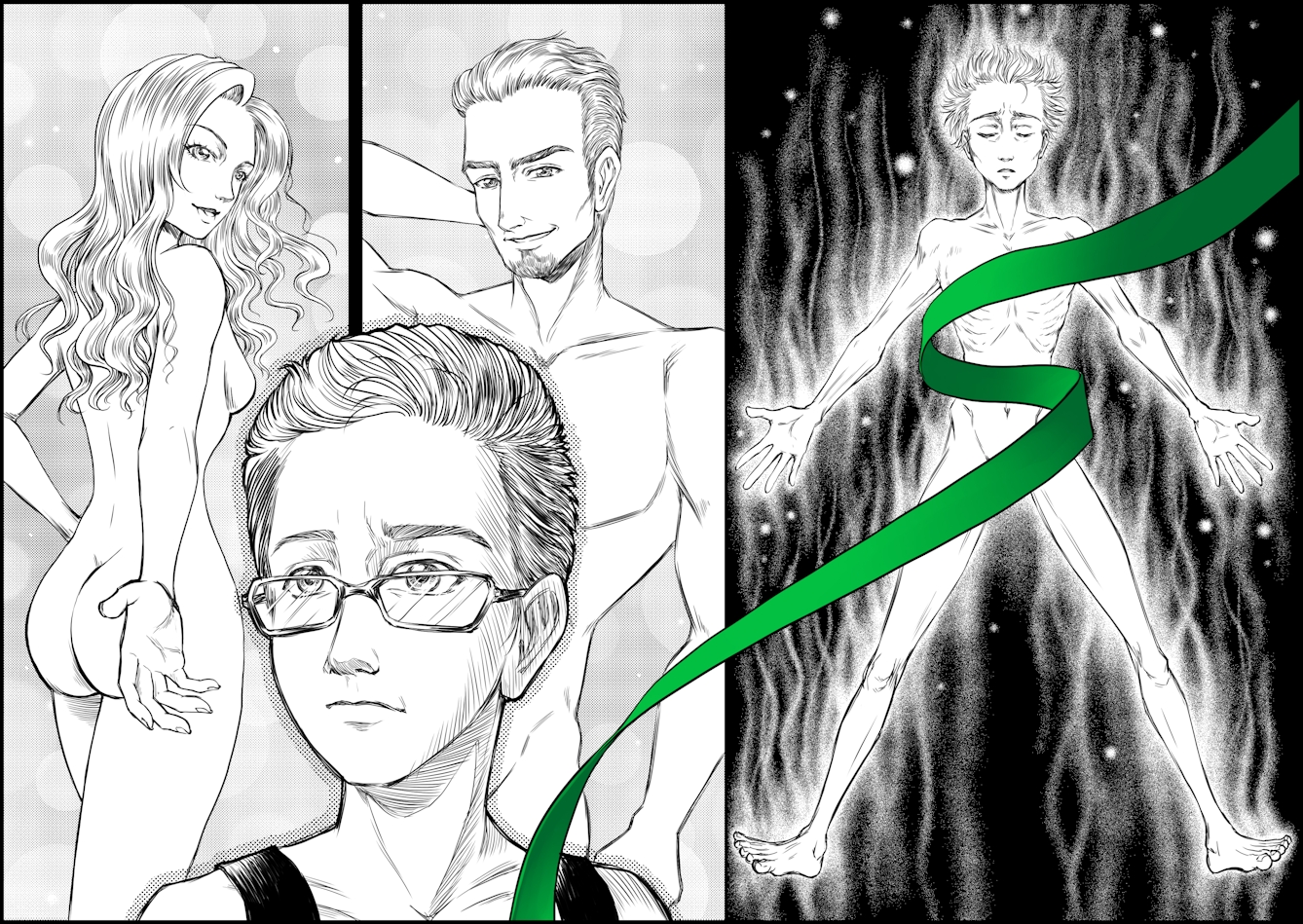

The addictive allure of horror

The older goth kids I knew would give them to me after the extracurricular art classes we had together. A girl with spiky blue hair introduced me to ‘Johnny the Homicidal Maniac’. A boy who always wore sunglasses and a large top hat, even indoors, introduced me to ‘The Sandman’. But the one that scared and disturbed me the most, the one I kept coming back to shudder at, the one that would quickly become my favourite, was a Japanese manga called ‘Uzumaki’.

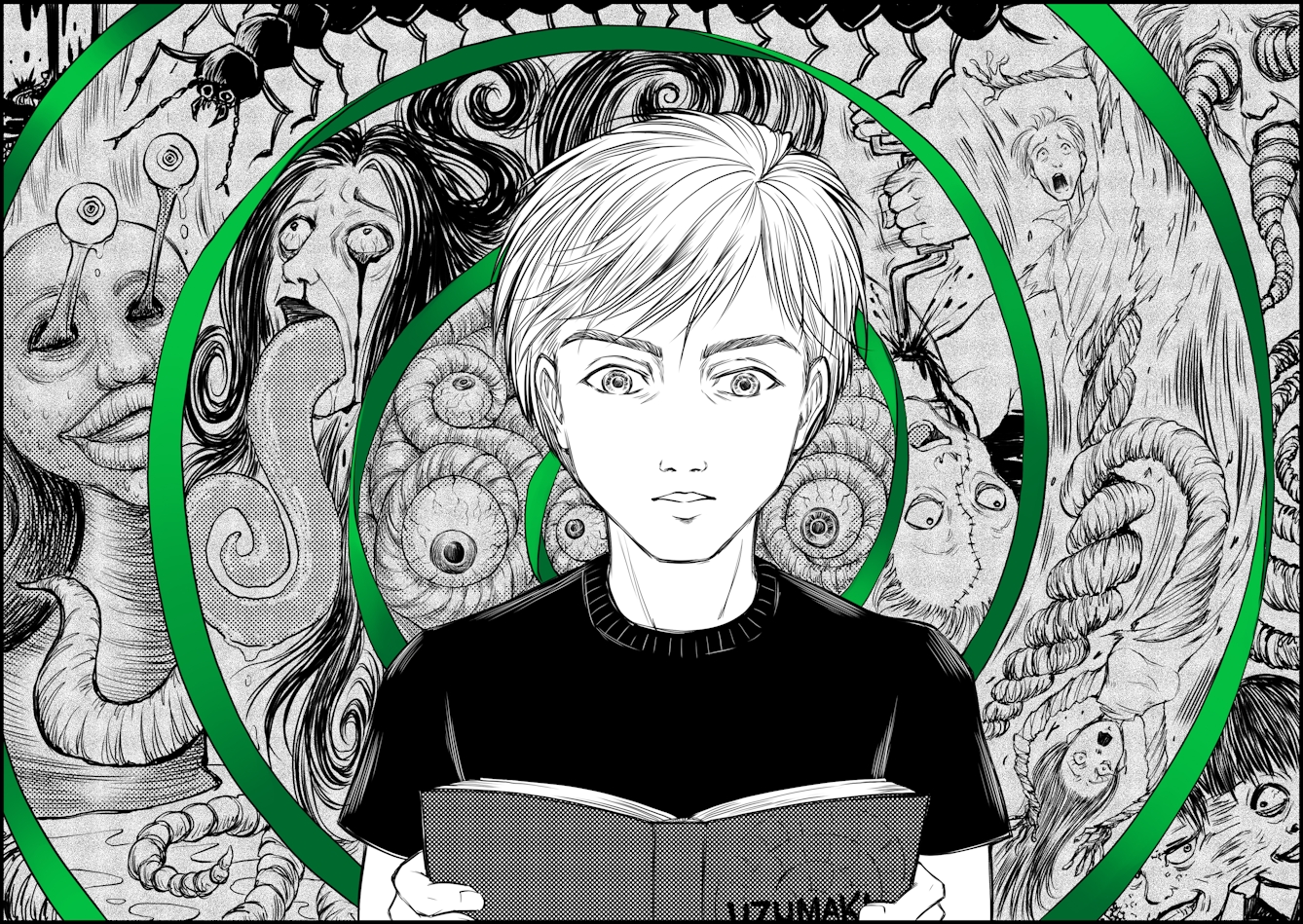

‘Uzumaki’ is among the best-known works of Junji Ito, a former dental technician who has been making a name for himself with surreal horror comics since the late 1980s. His medical background is evident in the anatomical precision with which he renders distorted humans, animals, plants and buildings.

In ‘Uzumaki’ (‘Spiral’ in Japanese), a teenage couple realise that strange and terrible things are happening in their home town, all connected by the presence of spiral shapes. For much of the story the two protagonists are the only residents who seem to understand the magnitude of what’s happening. They try to warn others, but are shrugged off as paranoid even when their friends and neighbours are transforming into giant snails, or drinking human blood through their new hollow, spiral-shaped tongues.

‘Uzumaki’ affected me as strongly as the story of the green ribbon had years earlier, but it was darker, more suited to the complexities of adolescence. Instead of being about one person’s struggle to keep her body safe, ‘Uzumaki’ was about two people trying to protect themselves, and each other, when they didn’t always know what they wanted or needed or what the rules were or what their bodies were going to do next.

The sickness was inside them and all around them, and it wasn’t implied or rendered with bloodless simplicity: every issue of the manga had at least one full-page illustration showing some spectacle of supernaturally mutilated human flesh. But where I had covered my eyes and ears in the face of poor Jenny’s secret, I couldn’t get enough of looking at the far worse fates of the characters in ‘Uzumaki’.

“Body horror says that even our worst, most disgusting experiences are not unspeakable.”

Learning to trust myself

I would not have the vocabulary to identify myself as transgender until I was in my late teens, and I wouldn’t come out to anyone until my twenties. I wouldn’t be diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, the genetic disorder responsible for my floppy ankles and frequently displaced shoulders, until a couple of years after that.

I still struggle off and on with disordered eating. My self-immersion in grotesque media wasn’t a shortcut to happiness. It didn’t give me immediate confidence in my own perceptions, or the wherewithal to seek appropriate medical counsel right away. But I believe it did play an important role in my perseverance. It helped keep a kernel of self-trust alive in me, even if I was confused and in pain and the world around me didn’t become any safer.

As an adult, I’ve made friends with others who are disabled, trans and queer. Not all of us enjoy horror fiction, but I’ve noticed that an awful lot of us do, and that those of us who like it almost always gravitate towards body horror more than other subgenres.

We can’t get enough of stories about the fragile precariousness of our meat and skin and bone. We often see ourselves as both monsters, at risk from a world that doesn’t understand us, that will untie the ribbons around our necks without a second thought, and as victims of unpredictable bodies that rebel or break down in lurid ways, that bear wounds and scars.

Body horror says that even our worst, most disgusting experiences are not unspeakable. It shows us how to tell our stories, and how to keep telling them, loud and relentless, as we walk into the future on rotting but steady legs, our bodies held together with ribbons and hope.

About the contributors

Briar Ripley Page

Briar Ripley Page currently lives in the north-eastern United States, where they write fiction, non-fiction and poetry.

Sonia Leong

Sonia Leong is a comics/manga illustrator and author of many drawing guides, including ‘Draw Manga: Complete Skills’ (Search Press). Her debut graphic novel was ‘Manga Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet’ and her most recent was ‘Great Lives: Marie Curie’. She also illustrates for children’s books, fashion, advertising, film and television.