The Museum of Transology (MoT) is a growing collection of over 250 objects chosen by more than 120 trans people to reflect their gender experiences. From human remains to an everyday can of Lynx deodorant, the collection is as diverse as the identities that fall under the ‘trans umbrella’. Curator E-J Scott explains what building the collection meant to him, particularly through the lens of trans masculinity.

The MoT collection is designed to capture the most significant shift in gender awareness in the UK since second-wave feminism in the 1960s and ’70s. Without it, there was a risk that the evidence that would survive about trans people would give an unbalanced picture.

What lived on would be the medical records that reductively pathologise trans lives, the media reports that vilify us, and the criminal reports that reflect the chronic levels of violence we face. It would be material that talked about us without including our voices. This is the most readily available type of material historians rely on today to find evidence of homosexual men in the past. History can be a poor listener. It also repeats itself.

My choice of objects to start the collection were inspired by an early memory from primary school. I have a recollection of students in my class bringing their gloopy tonsils into ‘show and tell’ after they’d had them removed. They’d float around in liquid in a little jar. My classmates and I used to think it was the best thing ever.

So before I had my chest surgery, I asked my surgeon if I could keep the breast tissue. It was my lifesaving trans ‘show and tell’. As far as I was aware, the physical record of surgical transition had not yet been collected by any medical museum in the UK.

Loaded with both technical and social significance, this aspect of trans history might have remained unrecorded, threatening to slip into the historical abyss like so much of the rest of trans history, or ‘transcestry’. Or worse still, it could have been found retrospectively in a medical journal, stripped of its emotional significance. Instead, with my story attached to it, what could have potentially appeared gruesome becomes entirely restorative.

Telling the stories of trans men

I also managed to save my hospital gown, the paper cups used to administer my painkillers, my pillowcase and towel, my hospital ID bracelet, the bloody bandaging that dressed my wounds and all the medical paperwork. Together they not only constitute the founding collection in the MoT, they also restore some balance to the way in which trans women’s bodies and lives are over-scrutinised. Indeed, of the many insights into trans lives revealed by the MoT’s collection, among the most striking are the rarely seen, intimate moments surrounding the formation of trans-masculine identities.

When the call went out that I was building this collection, donations poured in from other trans men all over the country. The objects held deeply personal significance that spoke of a plethora of trans-masculine experiences I had rarely seen documented.

The power of these objects is that they are both chosen by trans men and are about trans men, with the commentary handwritten in the first person. The donors’ everyday accounts completely obliterate the sensationalistic tone that media stories about trans lives have often adopted.

‘Suited’ by artist Simon Croft is made from over 100 cardboard boxes that contained vials of the hormone testosterone. Its tailored metaphorical elegance testifies to the culture of “collecting the self” that underpins the Museum of Transology. “For me,” says Croft, “taking testosterone is a vital part of making my masculinity visible and experiential, like putting on a really well-fitting suit.”

A young black trans man from London brought his favourite black baseball cap all the way to Trans Pride in Brighton, specifically so he could drop it off at the MoT’s stall at the festival.

The tag on the object he donated explains the influence his grandfather’s smart dress and etiquette had on his own understanding of what it means to behave like a gentleman. Significantly, it highlights the importance positive male role models play in the formation of adolescent men’s developing identities and values.

“MY FAVOURITE HAT… As a child, I would watch my granddad with pure adoration. He was always stylishly dressed in a suit and his best church hat… he had many beautiful qualities which I admire. Best of all, he was a gentlemen. He passed away before I could explain to him how much he shaped me as a person. He taught me kindness and, I’d like to think, many great, great qualities. He is also the reason I love hats.”

Finding hope in a hostile world

Social isolation – a frequent result of depression that stems from the constant and open vilification of trans people dished out by the media and on the street – was a recurring theme in the collection. Having been forced to flee the country town I grew up in, it resonated with me deeply.

Unexpectedly, it was a well-loved, chewed plush dinosaur toy that spoke to me the loudest. It represents the age-old legendary bond between a “man and his dog”, and how this relationship underpins and strengthens the contributor’s sense of self-worth. While loving one’s pet isn’t a gender-specific phenomenon, what is apparent is that this trans man’s masculinity is directly linked with his role as a primary carer: it directly reinstates a sense of hope and worth.

“This was my dogs beloved toy. My dog accepts and love me just as I am, I’m his Daddy no matter how I look or feel. Playing with him makes the world ok again, even if just for a few minutes.”

The beauty of the MoT’s collection is that its sheer size reflects the diversity of the trans-masculine experience. So while some of the objects shed light on living in a society that is seriously dangerous for trans people, others embrace the magic of what it means to have experienced the journey round gender’s globe.

With two in five young people having attempted suicide, sharing a thread of hope sends an important message to other trans youth who read this dilapidated dinosaur’s tag… Especially when it’s displayed alongside a metal pencil sharpener that has had a blade removed to use to self-harm “because of my gender and the things people say about me”.

"This sharpinar is something that has a missing Blade, I struggle with self harm and so I take them out, because of my gender and the thoughts people have about me."

For some it’s a religious experience. A Jewish man explains his trans-masculinisation of his kippah as being emblematic of his entire life trajectory, inextricably linking his religious values to the formation of his gender identity.

“This rainbow kippah (Jewish religious headgear) signifies the miracle of my journey: assigned female, tomboy, secular, coming out as queer, practising my faith, coming out as trans, transitioning, using my Hebrew name. In all this, I have queered the traditionally cis-male kippah, not just by the rainbow pattern, but by making it trans-masculine.” On loan from the Twilight People Collection.

A cheeky teenage kid uses his first ever boys’-school tie to explain how his education was interrupted by the enforcement of gender-segregated teaching. He had to change school in order to transition. Yet he doesn’t describe the situation for what it is: a despicable mishandling of every young person’s inherent right to a stable education.

Instead, equipped with a terrific sense of humour, he laughs in the face of adversity, foreseeing a bright new future ahead of him. His little tiny drawing of himself may not be a masterpiece, but it is masterminded. The self-portrait is deliberately laugh-out-loud silly. It shouts out: “Stay strong, everyone!”

The boy’s uniform is a symbol of strength. He’ll never know the impact his message has had on me at times when my own trans courage has needed restoring.

“This is the first tie that I wore on my first day living fully as a boy. I moved school to transition as my previous school taught boys and girls seperately (weird right?!). This tie means so much because it was like a new birth day, no longer living in the past but having a new and more positive future. Stay strong everyone. Max.”

Flashes of enlightenment

These moments of joy demonstrate that not only does the MoT play an important role in educating non-trans people about the realities of trans life, it also functions as a much-needed source of celebration for members of the trans community. It’s full of testimonies of trans enlightenment that flutter like gender fairies sprinkling sparkly trails of hope to boys who just want to be left to experience the magic of growing up.

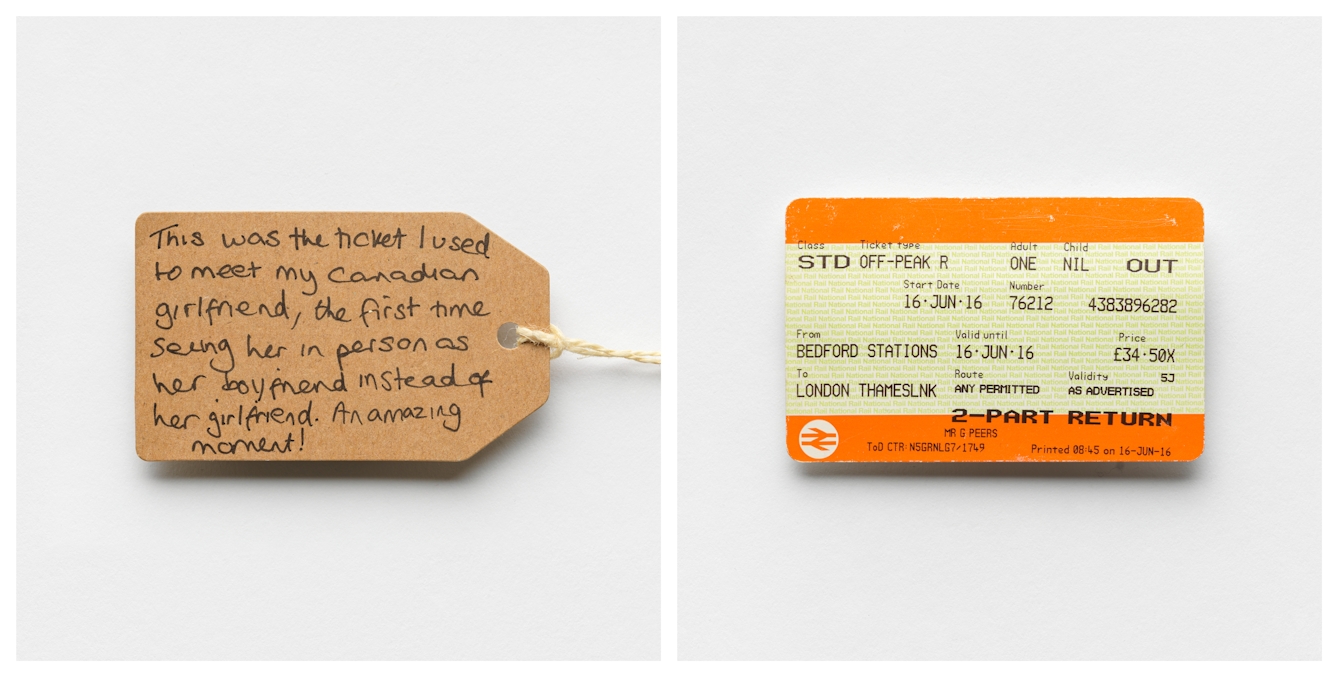

A train ticket from Bedford to London that one young trans man used to meet his girlfriend as her boyfriend for the first time is a physical marker of his rite of passage to manhood. It’s an example of healthy masculine pride that sits in complete opposition to examples of toxic masculinity and brutish bravado that improperly influences so many young men’s understanding of how to prove they’re men, not boys.

“This was the ticket I used to meet my Canadian girlfriend, the first time seeing her in person as her boyfriend instead of her girlfriend. An amazing moment!”

What does it mean to be a trans man? he asks. It means being true to yourself.

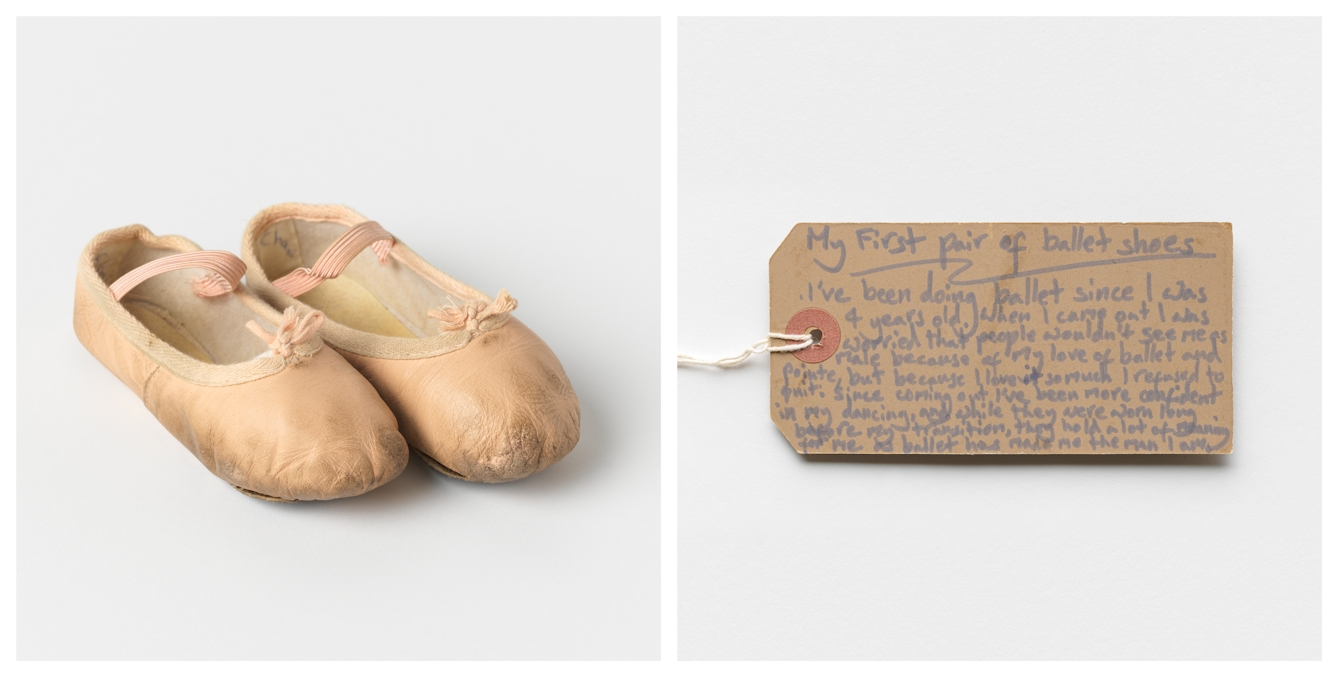

But it’s the teeny-weeny pair of baby-pink ballet slippers worn by a four-year-old child that I find most poignant. They reflect the immensely thoughtful way in which a young trans boy grappled with, and ultimately rejected societal expectations to adhere to masculine stereotypes. He exposes his personal struggle with comprehending masculinity with complete transparency. What does it mean to be a trans man? he asks. It means being true to yourself.

“My First pair of ballet shoes: I’ve been doing ballet since I was four years old. When I came out I was worried that people wouldn’t see me as male because of my love of ballet and pointe, but because I love it so much I refused to quit. Since coming out I’ve been more confident in my dancing, and while they were worn long before my transition, they hold a lot of meaning for me, as ballet has made me the man that I am.”

With suicide the leading cause of death among men aged 20 to 40, perhaps it’s time we all looked closely at the gender awareness embedded in this collection. These trans men show a willingness to speak openly about the challenges gendered life throws their way. From this, others can learn about the emotional impact of these challenges, and the coping strategies they’ve developed to lead fulfilling, rewarding and responsible lives.

About the contributors

E-J Scott

E-J Scott is a curator and queer cultural producer. His work focuses on skilling members of the LGBTIQ+ community to delve into the queer past and build queer public history events as a form of peaceful museological activism. His work includes: founding the Museum of Transology (Bishopsgate Institute); curating ‘Queer & Now’ at Tate Britain (2018 and 2020); working as Duckie’s Archival Researcher for its Queer History Club; he has also has helped over 30 queer volunteers to make their own exhibition at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery, ‘Queer the Pier’ (2020–22).

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.