Aparna Nair has learned to live with the risks and confusion that can accompany an epileptic seizure. But dealing with the shock and concerns of those around her has proved just as challenging.

The first seizure

Words by Aparna Nairartwork by Tracy Satchwillaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

I was eleven when my brain first betrayed me. My family and I were at my grandparents’ sprawling old house in southern India. We sat around the oval dining table eating a meal that I still remember vividly: wheat chapatis, curry redolent with spices and coconut milk, and a tangy carrot salad.

As always, the Kerala night was warm and humid during the monsoon season. The fan spun pointlessly in the middle of the room, and a dull tube light wavered.

Slowly my eyelids began to flicker uncontrollably, almost in tandem with the light. I forced my eyes shut, not understanding why I couldn’t make them stop. I felt as if I was floating outside my body as I watched the family talk and eat. My skin prickled as waves of goosebumps raised across my body despite the heat that was leaving droplets of sweat on my skin.

As the night went on, my mind became incapable of processing the conversation around me.

I remember my first seizure in flashes, like an old silent film.

I don’t remember much of the rest of the night. But I remember my first seizure the next day in flashes, like an old silent film. It happened as I crouched down in front of an ancient analogue television, trying to adjust the image, my face only a few inches from the screen showing black and white dots of dancing static.

I remember falling, hard, onto the mosaic floor, before the darkness drew me in. It felt like I had leapt off a cliff backwards into an inky chasm shot through with pain and confusion. As I slowly pushed away the tendrils of darkness and struggled back to consciousness, the first thing I heard was a terrible, animalistic whimpering. I didn’t realise that the sound was coming from me. My family stood around, shock, concern and fear on their faces.

A print by Jean Duplessis-Bertaux (1750–1818) showing a group of people standing around a man having a seizure in public.

The falling disease

Two years later I was diagnosed with epilepsy. One among the 50 million people who live with the condition worldwide. Seizures can be a very public symptom of epilepsy, especially if they occur with little warning.

I have found myself waking up from the fog of a seizure in many places: on the cold and wet floor of a bathroom as the shower sputtered water around me; in a rickshaw hurtling through the chaos of Indian traffic; on a concrete pavement by the side of an American road; and in the back seat of a taxi, surrounded by emergency medical personnel and a steely-eyed policeman with his hand on his gun. Not for nothing was epilepsy known as “the falling disease”.

And along with falling comes the real danger of physical injury. I’ve woken up with blood seeping from unseen wounds and dripping down my body as I try to figure out where I am hurt. I’ve woken up with my lips swollen, cut and bleeding and teeth shaken loose. My fears of harming myself during a seizure have become a part of my life.

Yet despite the pain, injuries and confusion, what has always disturbed me about having a seizure is the expressions on people’s faces when I surface into consciousness, often a combination of disgust, revulsion and fascination.

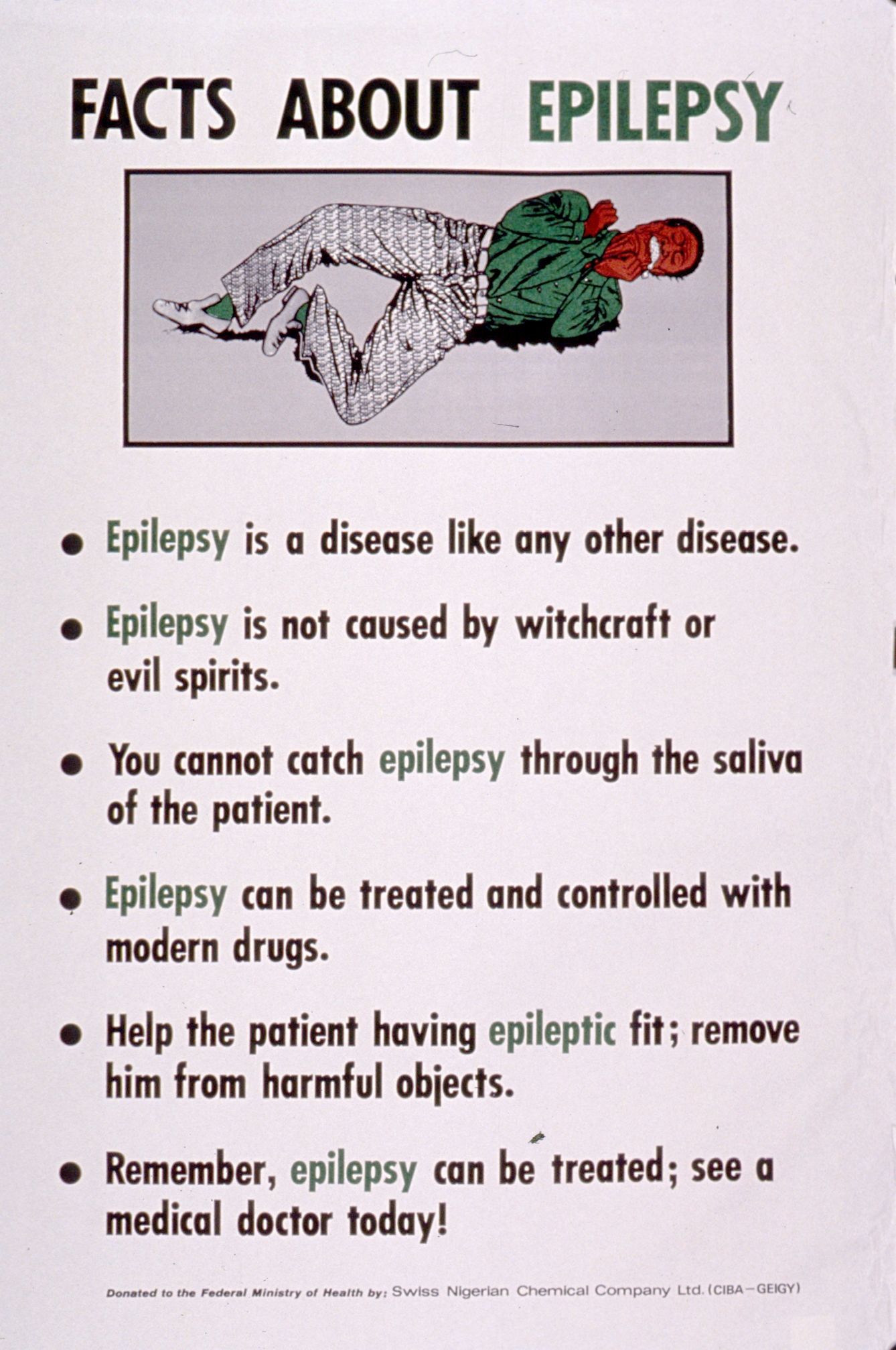

A public heath poster produced by the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health and the Swiss Nigerian Chemical Company Ltd.

A supernatural explanation

Seizures can take many forms, but they are often accompanied by loss of control of the body and mind, and a profound loss of self-awareness. At their worst, they can appear to momentarily erase what makes us human: our very consciousness.

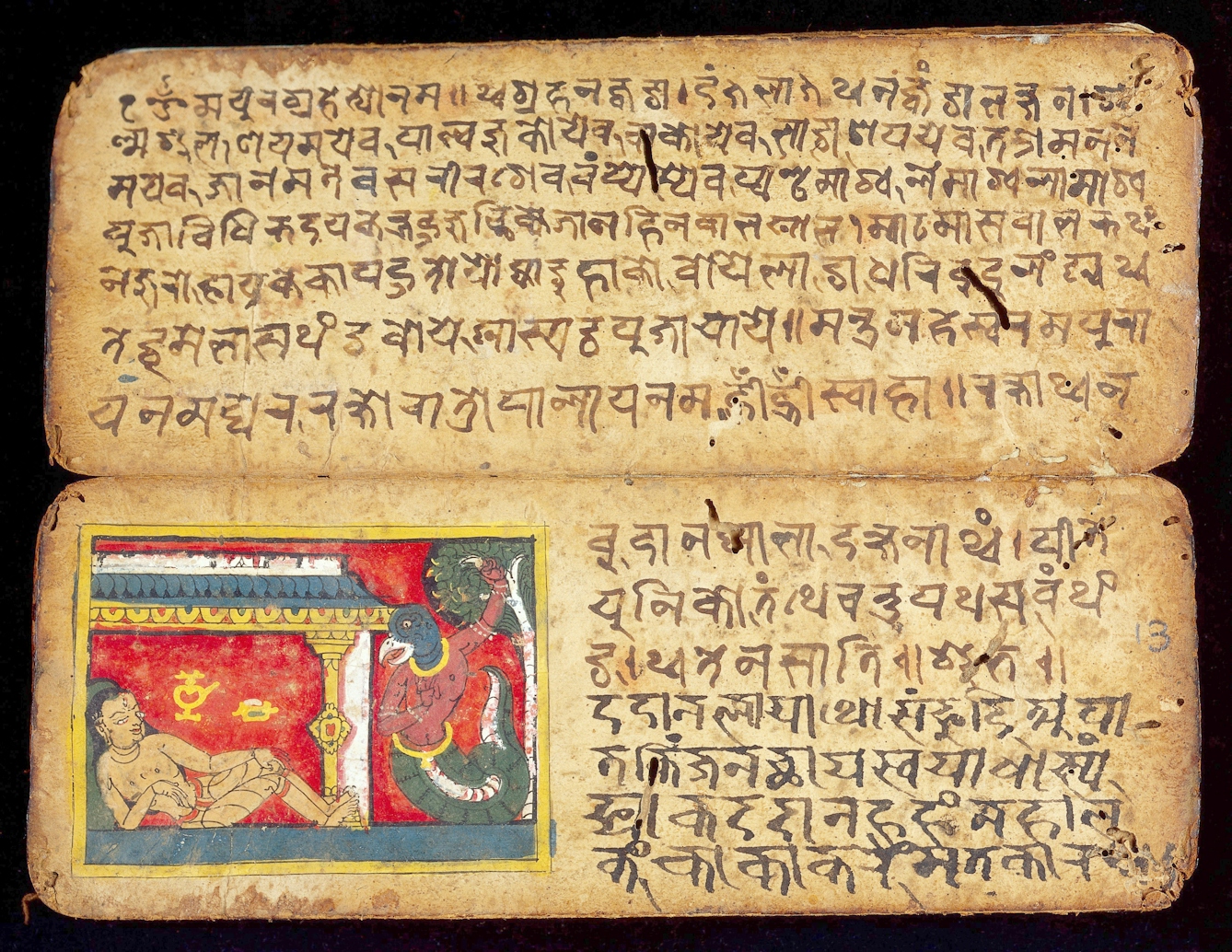

In the past, the strange, dehumanising appearance of seizures was often associated with supernatural causes. An ancient pre-Babylonian text, ‘Sakikku’ (c. 626–539 BCE), mentions barren demons who spitefully afflicted children and young people with seizures. In Hindu mythology, seizures were thought to have been caused by either the minor goddess Grahi (“she who seizes”) or the dog demon Kurkura.

A Nepalese manuscript showing a bird-headed Grahi spirit (1480 CE).

People who had seizures were viewed with fear, suspicion and hostility in many cultures. Laws and customs were developed specifically to deal those who exhibited this uncontrollable condition. The oldest confirmed description of a seizure is in the ancient Babylonian ‘Code of Hammurabi‘ (c. 1792–1750 BCE), which says that a slave can be returned if they have a seizure in the first month after purchase and the purchaser has to be refunded.

In ancient Rome, seizures were called ‘Morbus comitalis’ and thought to be a bad omen. If someone had a seizure during a public assembly, the assembly was discontinued, and the gathering was dispersed. The Roman slave Thallus was prone to seizures and his fellow slaves complained that “nobody dares to eat with him from the same dish or to drink from the same cup”.

In the classical Hindu text the ‘Laws of Manu‘ (c. 100 BCE), those who had seizures couldn’t partake of offerings made to the gods, while women who had seizures or who had a family history of seizures were prevented from marrying.

St Valentine blessing a man with “falling sickness”, a historic term for someone who had seizures.

The belief that seizures were supernatural possession or divine punishment continued well into the early modern period in Europe too. Several Christian saints, including St Germain (496 –576 CE) and St Ignatius de Loyola (1491–1556 CE), were said to have cured sufferers of seizures by exorcising the devils that tormented them. The historic association with the supernatural is reflected in the common names for epilepsy: in French it’s known as le mauvais mal (the wicked disease) and in German böses Wesen (wicked spirit).

Throughout history, the seizure as a symptom elicited fear, anxiety and suspicion. And I wonder how often people around me still feel the same way when they see me in the midst of a seizure.

- A sentence stating that the Code of Hammurabi banned marriage and giving testimony by people who had seizures has been removed from this article, at the request of the author, because there was insufficient evidence for this statement. Changed 6 February 2020.

About the contributors

Aparna Nair

Dr Aparna Nair is an assistant professor in the Department of History of Science at the University of Oklahoma. She works on disability, medicine and colonialism in India in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as disability in popular culture and the experience of epilepsy in South India.

Tracy Satchwill

Tracy Satchwill was born in London, grew up in South Wales and is now based in Norfolk. Working across film, collage, photography and installation, her art practice explores female power, reflecting on its removal or reclamation. She weaves personal narratives into her work, exploring identity, oppression and vulnerability to combine the feminine with the surreal, the uncanny and the weird. Satchwill has exhibited at galleries and institutions across the UK and internationally. She also works on public commissions and residencies, focusing on women’s experiences.