One way to tell whether you are dealing with a saint is to sniff them. Osmogenesia, or the Odour of Sanctity, is the sweet and pure aroma that Christian saints and even their dead bodies are said to produce. The floral fragrance of a medieval saint was in vivid contrast to the body odours of others, who were told perfume was sinful and bathing a health hazard. The past was a place of smells both divine and disgusting.

In the Book of Genesis God breathed life into Adam’s nostrils, as shown in this allegory of smell. The Latin poem reads: “The sense of smell, the fragrant flower of the grateful lover / He has love of Hybla, flowering Hymettus, how sweet is this God / He infuses the man of salt with his own great gift of life.”

Pleasant smells were long thought to be divine, with pagan gods feeding on the savoury fumes of a burning sacrifice. In this image the newly born Virgin Mary is shown being bathed and cleaned for her future role as Mother of God, alongside a quote from the Song of Solomon, “the vines with the tender grape give a good smell”.

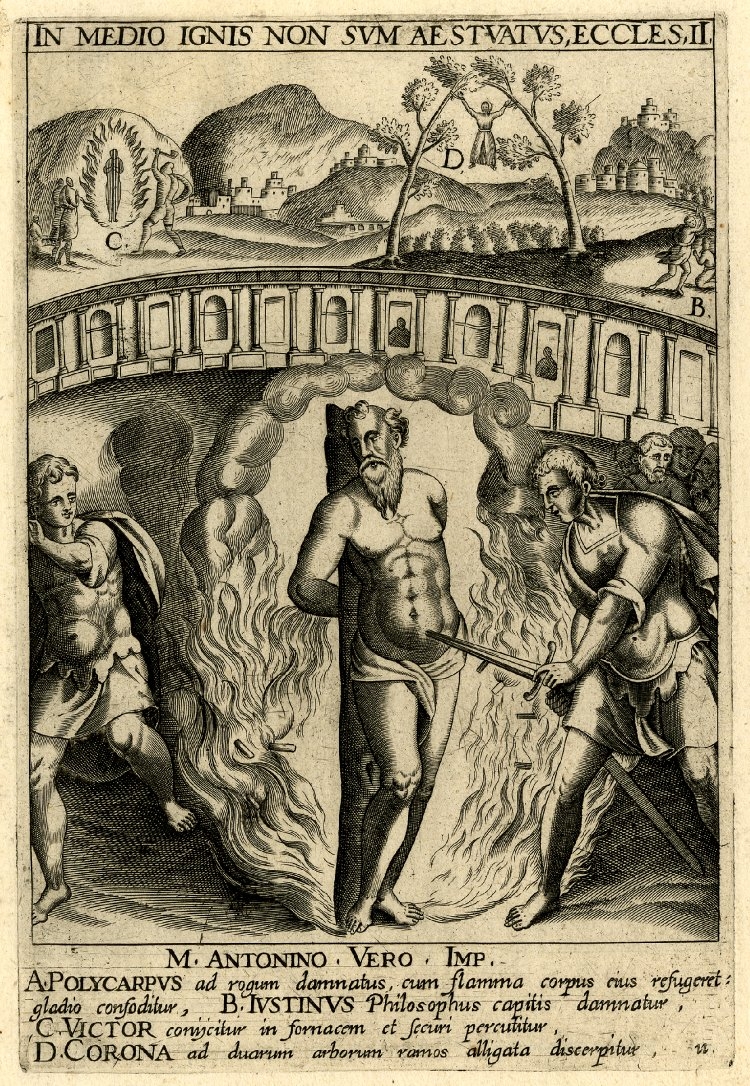

St Polycarp of Smyrna was an early Christian martyr. Ancient people would have been familiar with the stench of cremation, but when set on fire the saint did not burn with acrid fumes. Instead those watching “smelled a sweet scent, like frankincense or some such precious spices”.

Soon the Odour of Sanctity was a recognised sign of holiness, and pilgrims to shrines could collect holy oils to take that scent home. St Menas flasks were mass-produced in the 5th to the 7th centuries for visitors to his Egyptian shrine.

For hundreds of years the bones of St Nicholas have been said to ooze fragrant oils with healing powers. Each year this ‘manna’ is collected on 9 May and given to the faithful. One flask of oil from the 13th century was tested and proved to be oil from a vegetable source.

When a fire damaged the sarcophagus of William FitzHerbert, 12th-century Archbishop of York, a sweet smell and oil were seen to flow from it. Before the Reformation in the 16th century, the shrine of St William of York – as William was canonised 73 years after his death – was fitted with spigots to allow pilgrims to fill bottles with the holy perfumed oil.

Many still believe that scented oils emanating from the remains of saints are spiritually and physically healing. This set of vials contained the oil of St Walburga.

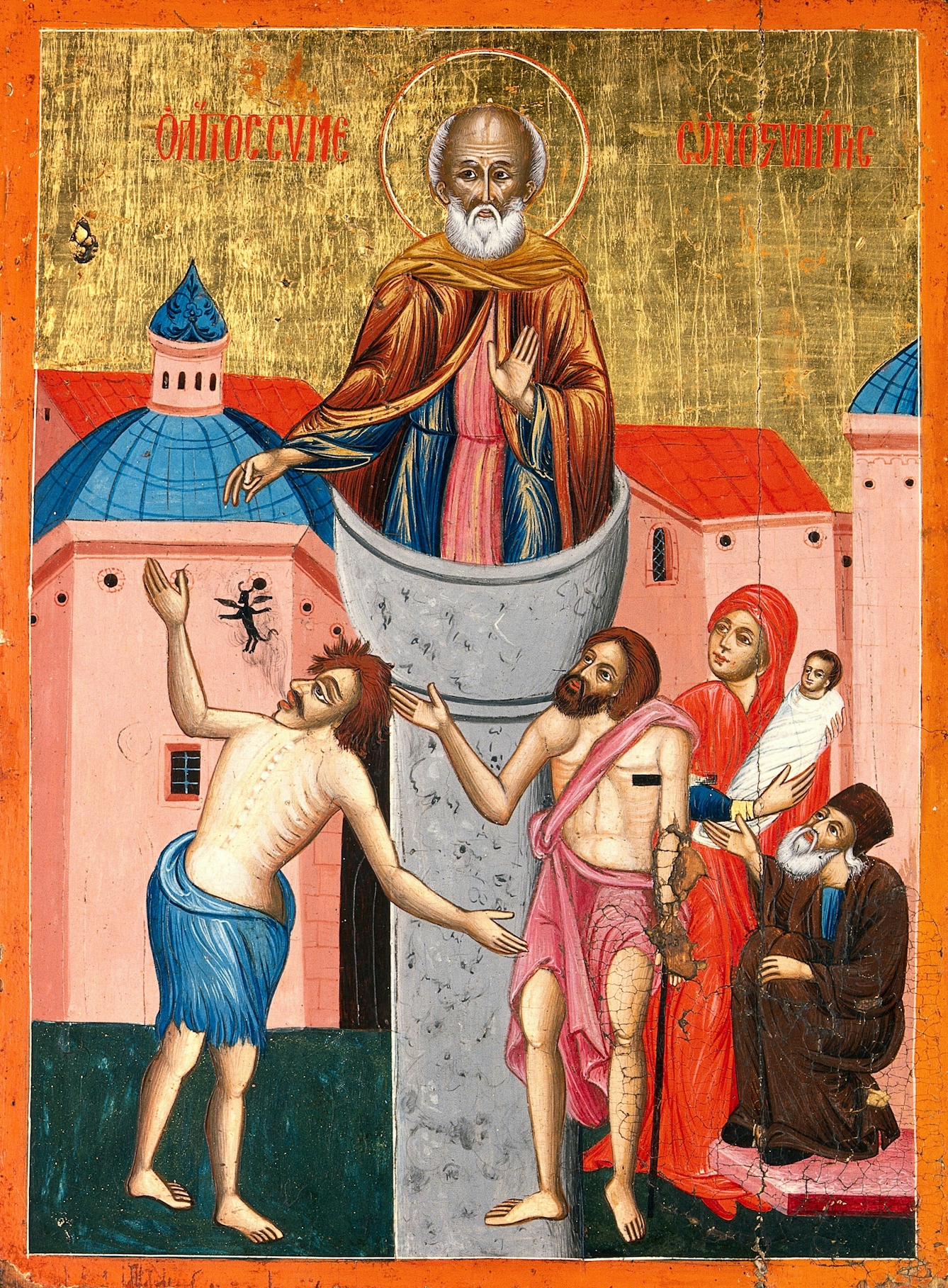

Simeon Stylites took monastic asceticism to the extreme, spending years alone on a high pillar. He mortified his flesh until it rotted and stank. Yet as he was dying he exuded a heavenly aroma – “neither spices nor sweet herbs and pleasant smells, which are in the world, can be compared to the fragrance” – indicating a state of physical purity.

The Odour of Sanctity is not for saints alone, however. A huge censer, the Botafumeiro, swings through the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela to welcome and cleanse pilgrims. The incense it spreads helps control the smell of thousands of visitors, which might be unbecoming to the sacrament.

About the author

Ben Gazur

Dr Ben Gazur has a PhD in biochemistry but gave up the glamour of the lab to be a freelance writer. He specialises in history, science, and the history of science. Ben Gazur is a writer and author. His book about food folklore is currently being crowdfunded. If you support it, you will get your name printed in the book. Click here to find out more.