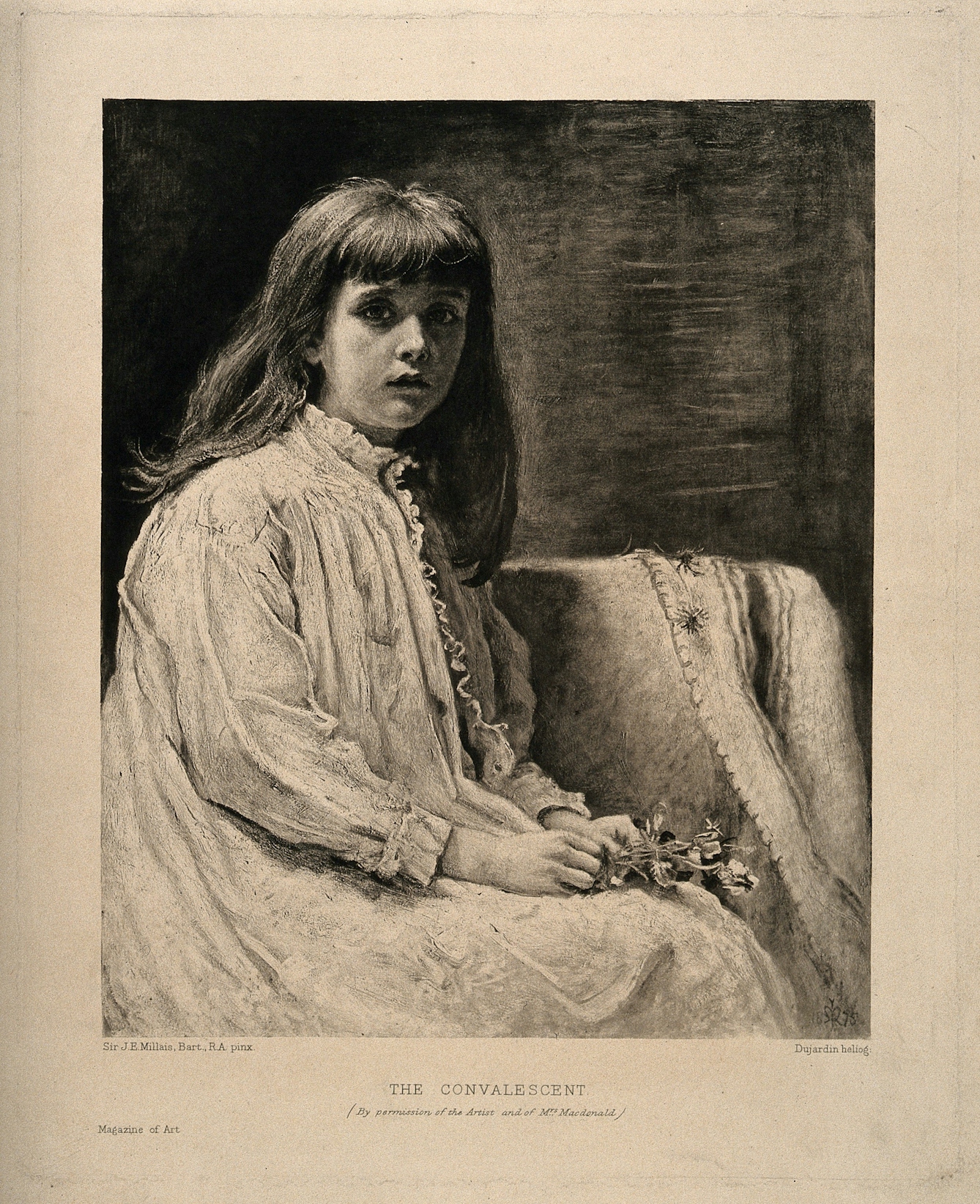

Convalescence is the gradual return to health after illness or injury, a gentle process of recovery. But whereas the heroines of 18th-century novels were apt to read and rest while sipping broth in a lace nightdress, nowadays we’re expected to be back at work as soon as the acute phase of an illness has passed.

The lost art of convalescence

Words by Lizzie Enfield

- In pictures

“You won’t feel yourself again for a while,” the consultant said, discharging me after I’d spent four days in hospital with a kidney infection. “So take it easy, do as little as possible, look after yourself and let your body recover.” Unlike a Victorian heroine, I felt that I was too busy, and instead threw my body in at the deep end and expected it to cope. Convalescence is a lost art.

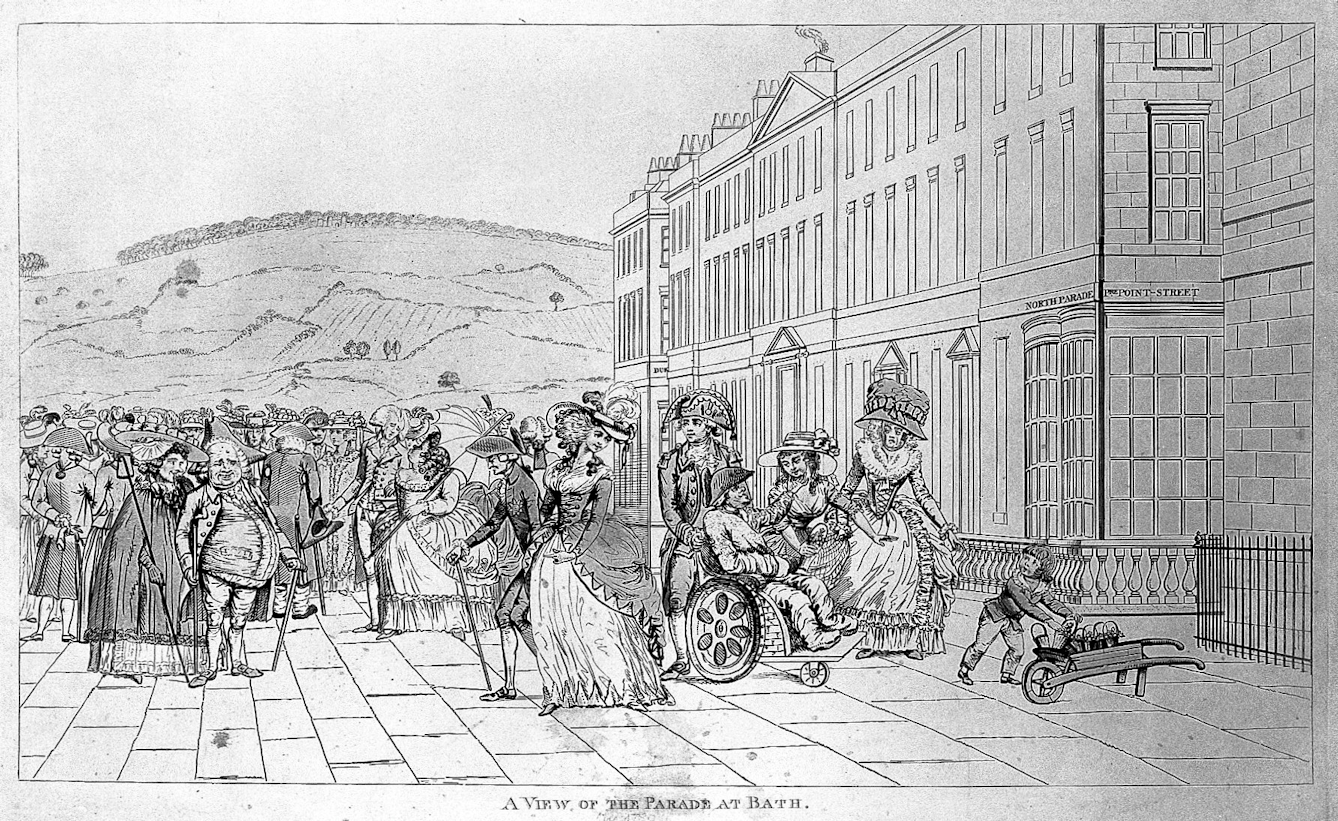

The Victorian poor often had to rush back to work too, but wealthy convalescents could afford to travel to spa towns, or mountain or coastal resorts to recuperate after illness or injury. Cities like Bath were founded on a belief in the restorative powers of their waters, and flourished in the 18th century, in part due to the influx of sick and convalescing visitors.

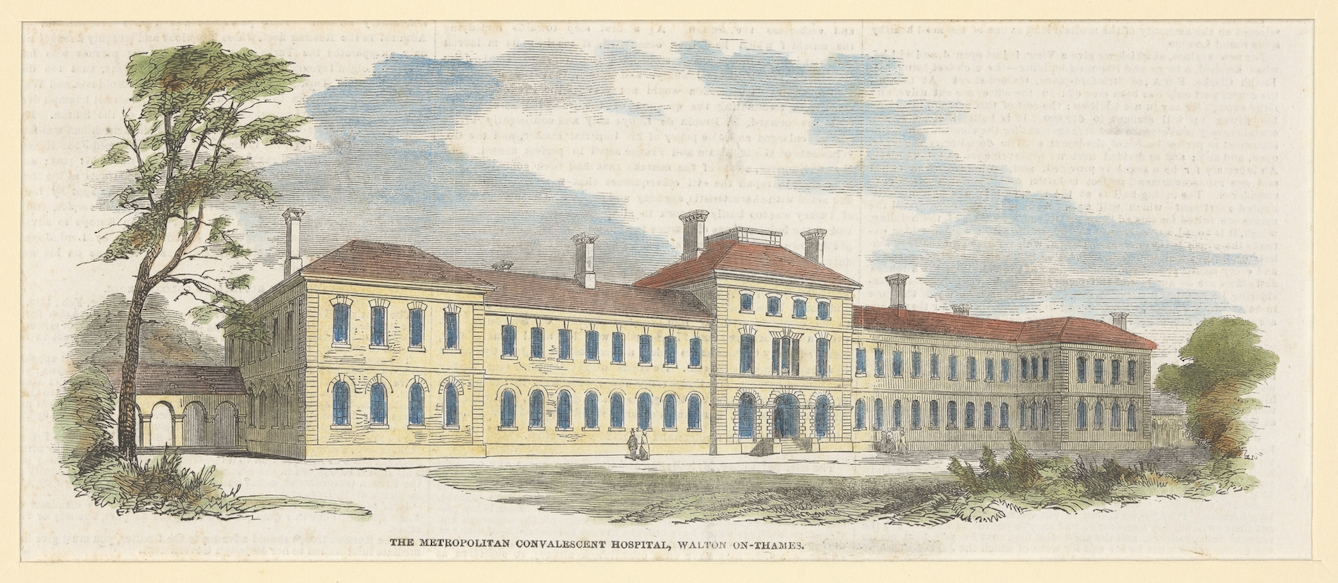

The Victorian poor had access to charitable hospitals, but returning to overcrowded slums had a pronounced impact on their chances of recovery. As the population of working-class patients treated in city hospitals increased, reformers and philanthropists established convalescent homes where these patients could recuperate away from the stresses of their normal working lives. One of the first was at Walton-on-Thames, formed in 1840 from the old Carshalton workhouse.

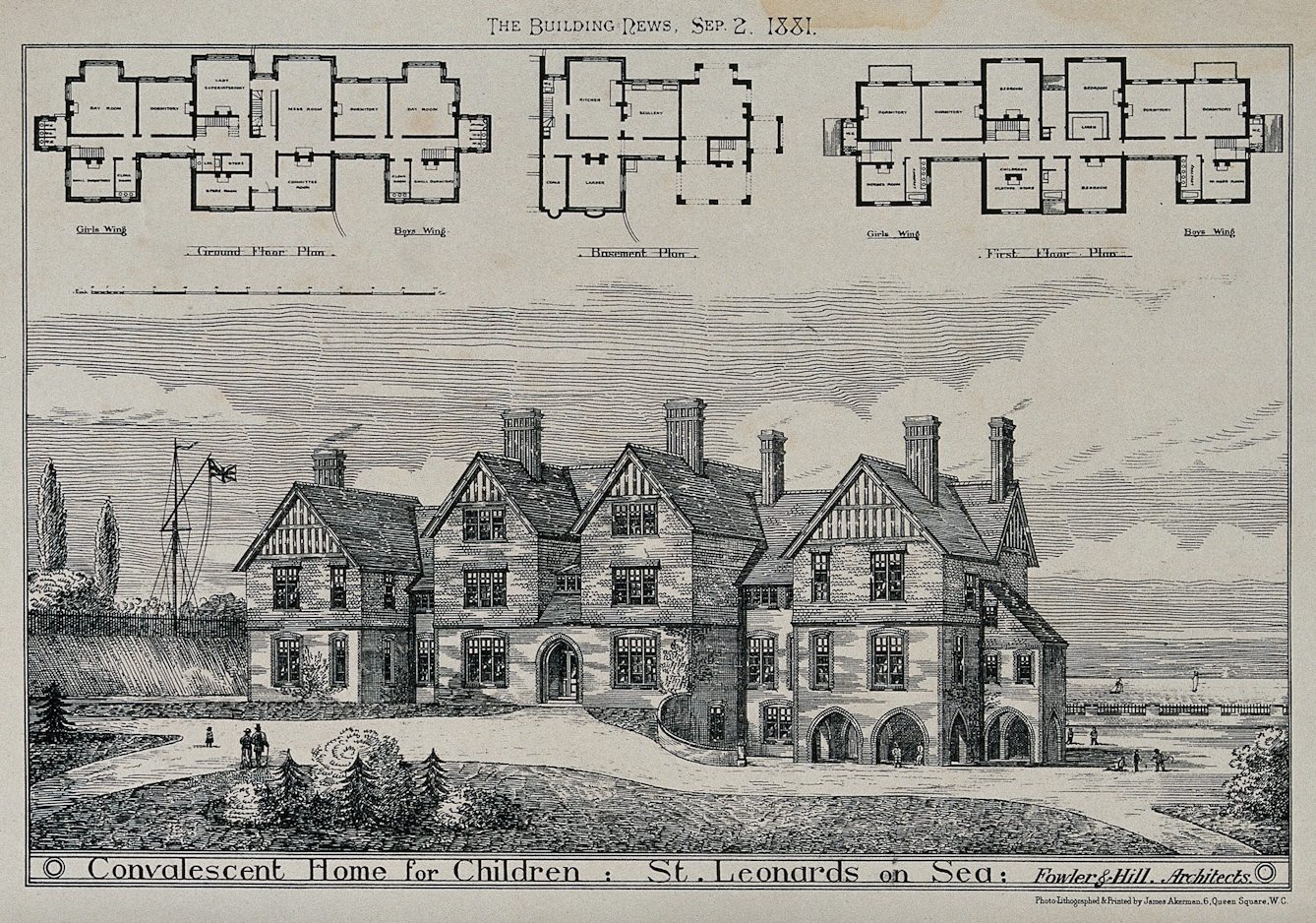

Convalescent homes were built away from the cities, in the countryside or in seaside towns where there was plenty of fresh, healthy air. A prime example was the Kewstoke Convalescent Home in Weston-super-Mare, established in 1931 by the Birmingham Hospital Saturday Fund for use by convalescing women from Birmingham. It became something of a showplace, showing the world what could be done in pursuit of a high ideal.

One of the greatest advocates for convalescent homes was Florence Nightingale. Ideally, she would have liked to change both hospital design – as she outlined in ’Notes on Hospitals’ (1859) – mainly to improve ventilation and hygiene, and location (moving them to the outskirts of major towns and cities). However, given the impracticality, she instead recommended building convalescence cottages in the country or by the sea.

The biggest urban disease of the Victorian era was tuberculosis (TB). Overcrowding helped TB to spread, and the polluted city air hindered recovery from it. The victims were often the poor, the homeless and the malnourished – those whose immune systems had been weakened by their living conditions. The favoured treatment before antibiotics was to remove the sufferer to the countryside and nurse them, where possible, outside.

By the end of the 19th century more than 300 convalescent homes had been established in Britain, catering to the needs of particular groups. There were homes for working men, soldiers, women and children.

Like the contemporary health farm or resort, convalescent homes were not just about fresh air, rest and recuperation. Diet and the provision of nutritious food were just as important, and the principle of convalescence was behind some of the diet books of the day.

Vast improvements in housing and sanitation, together with antibiotics, have made convalescence an almost obsolete word. Patients are able to leave hospital almost as soon as the acute phase of an illness is over, but that doesn’t mean the immune system has recovered. However, it needs to in order for the patient to stay well. In today’s busy world, convalescing, wherever it happens and whatever form it takes, is still an important part of the recovery process.

About the author

Lizzie Enfield

Lizzie Enfield is a journalist and regular contributor to national newspapers, magazines and radio. She has written five novels, and had her short stories broadcast on BBC Radio 4.