Before a young Parisian doctor developed a treatment for bladder stones in 1824, dealing with them was a dangerous and often deadly business. Find out how Jean Civiale refined and demonstrated his groundbreaking technique.

The extraction of the excruciating bladder stones

Words by Thomas Morrisartwork by Emily Evansaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

In 1782 a wealthy French expatriate in India, Colonel Claude Martin, began to suffer from a bladder stone. It was an uncomfortable complaint that made it difficult to urinate, and the retired army officer was soon forced to give up horse riding and many of his favourite foods. But it was also worse than a mere inconvenience: left untreated, the condition might well kill him.

Colonel Martin was told that the only possible cure was a painful and dangerous operation. Understandably, he was not enthusiastic about this prospect, so the resourceful Frenchman set about finding an alternative.

His solution was a homemade surgical instrument fashioned from a knitting needle. He inserted this implement up his own urethra and into his bladder, filing small fragments off the stone to break it down. He repeated this eye-watering procedure three times a day for six months, after which he reported that the stone had completely gone. And he had become one of the few people to operate on their own body.

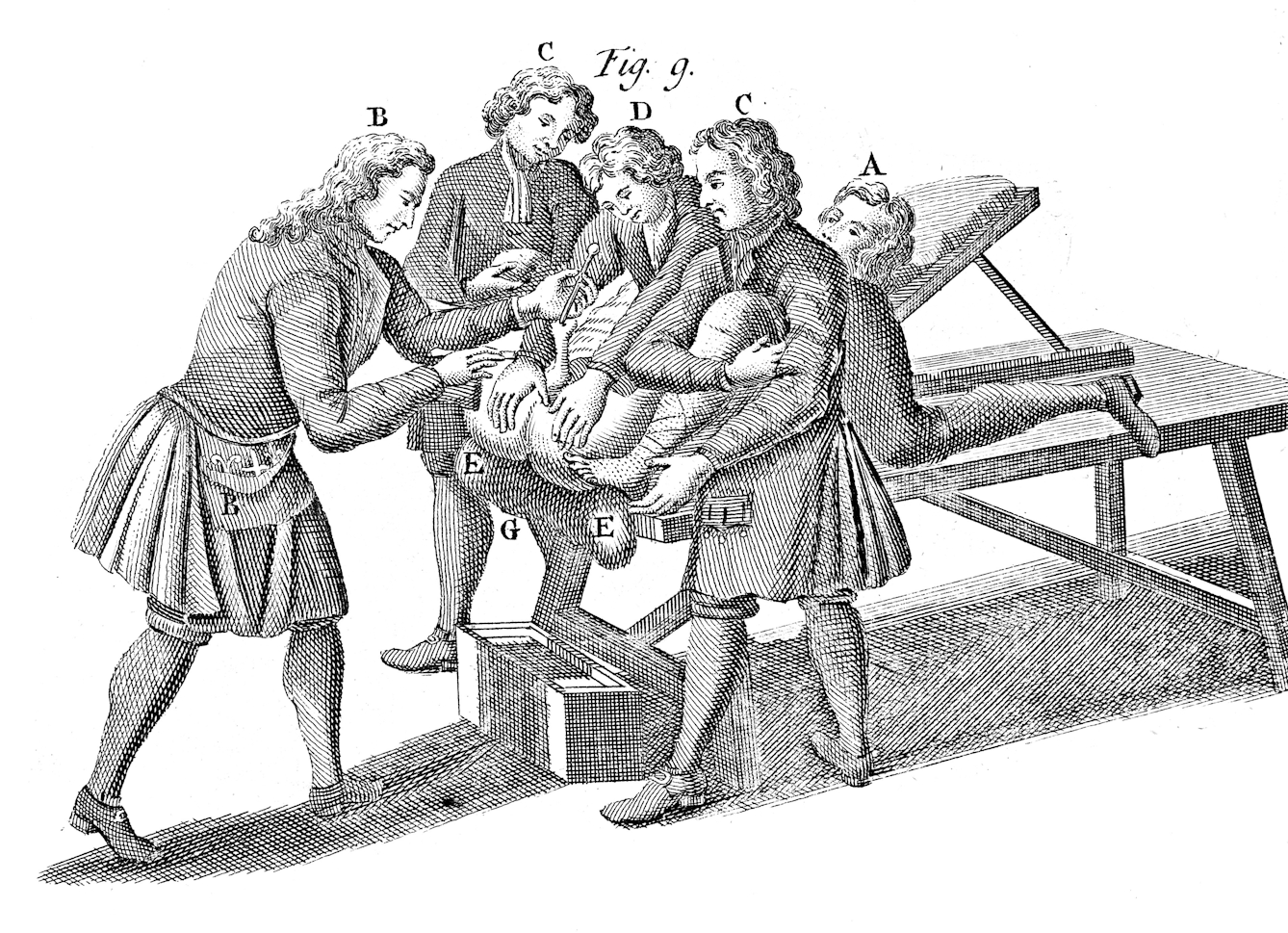

An early lithotomy, c.1768.

Treacherous treatment for a painful problem

Bladder stones, hard masses that crystallise from minerals in the urine, have afflicted humans for thousands of years. Ancient Indian and Egyptian surgeons invented procedures for removing them, which are documented in some of the earliest surviving medical texts. Substantial improvements were made to the operation, known as lithotomy, between the 16th and 18th centuries, but all entailed a large incision, which inevitably damaged delicate tissues and brought the risk of infection.

In an age before anaesthetics it was excruciatingly painful, and the danger was enormous: a large proportion of patients died, and many more were permanently affected by incontinence, persistent wounds, and (for men) erectile dysfunction. Small wonder that Colonel Martin was keen to avoid this ordeal.

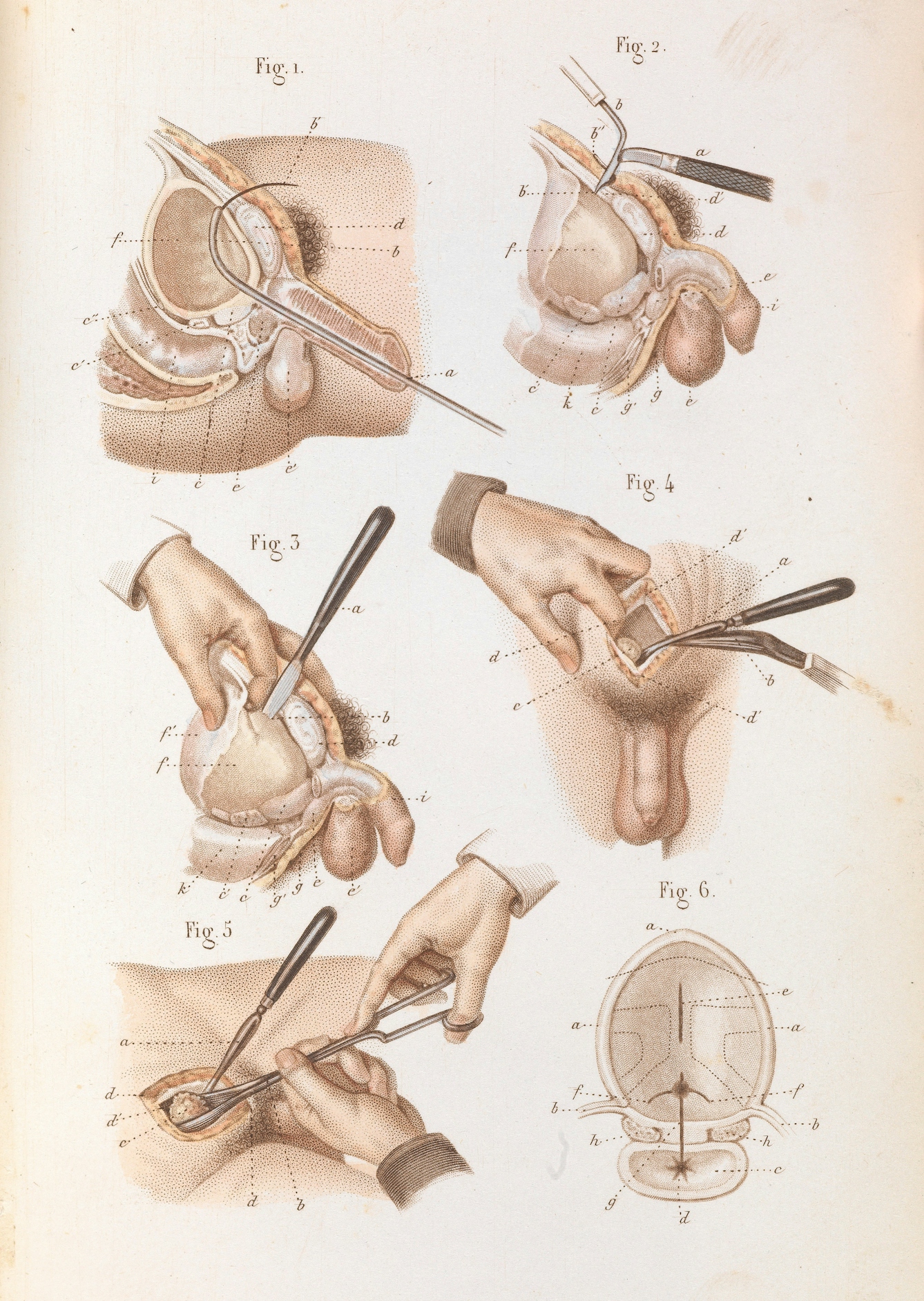

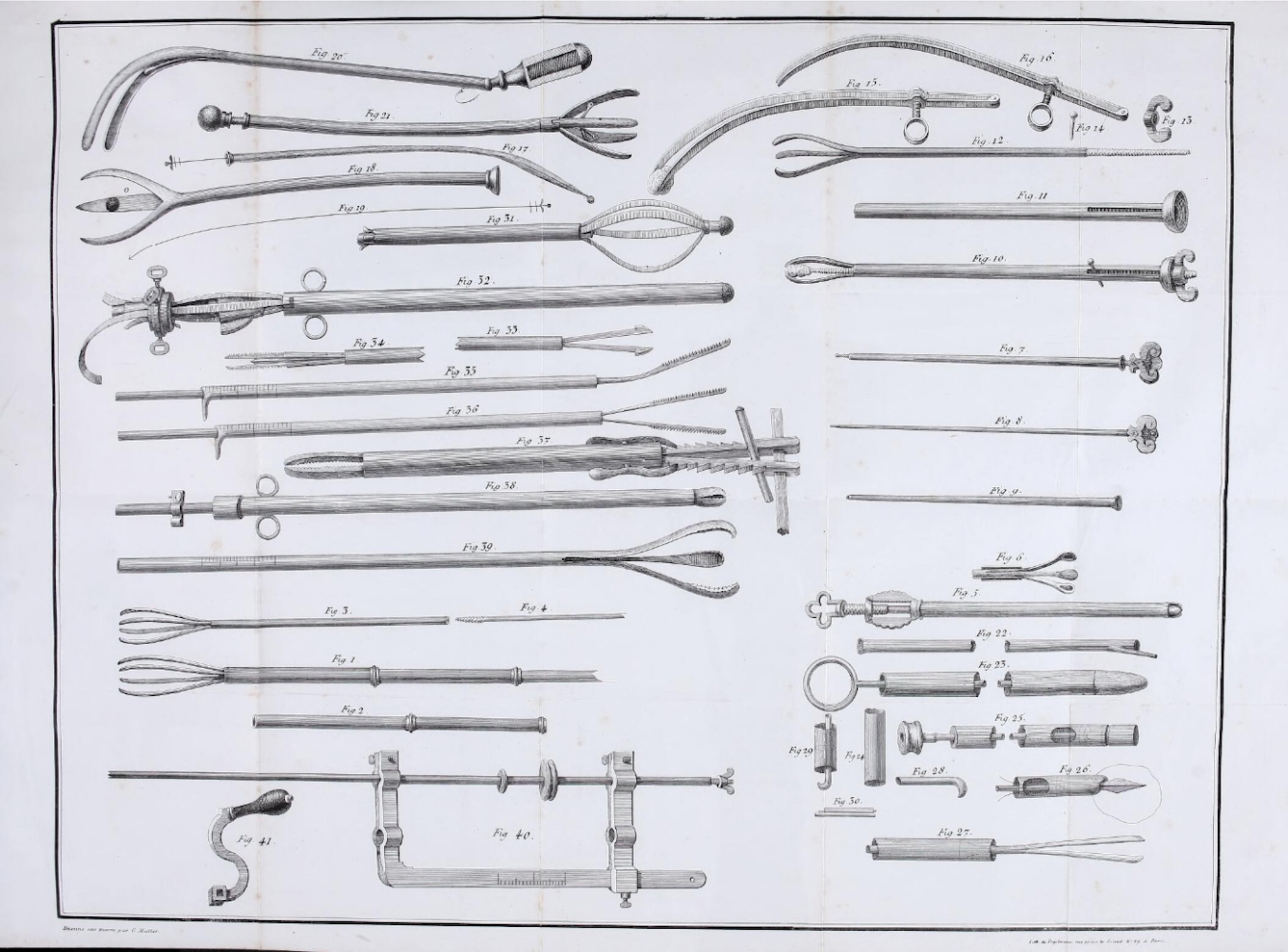

Surgical removal of a stone from the bladder from ‘Précis iconographique de médecine opératoire et d’anatomie chirurgicale’ by Claude Bernard, 1848.

During the 18th century physicians started to look for a gentler way of treating bladder stones. Some tried to develop medicines that would disperse them naturally. In 1738 a certain Joanna Stephens claimed that she had devised an infallible cure for the complaint, and the British government paid her the enormous sum of £5,000 (around £600,000 now) to disclose her secret recipe. Its ingredients included soap, snails and burnt eggshells, and – like every such concoction dreamed up to treat the condition – it turned out to be entirely useless. Other researchers attempted to dissolve the stones by injecting special solutions into the bladder, but this was no more successful.

When the breakthrough finally came, it was strikingly similar to Colonel Martin’s approach. In the space of a few years, several researchers hit upon the idea of using delicate instruments to remove bladder stones via the urethra – doing away with the need for an incision. In 1813 the Bavarian physician Franz von Paula Gruithuisen unveiled a series of instruments he had invented, and which offered a variety of ways to break down the stone in situ.

This was an uncomfortable experience for the patient, but infinitely preferable to the agonies of surgery.

One employed a powerful jet of water to dissolve the object; another used the heat from an electric current; a third had a tiny drill bit at its tip. But Gruithuisen’s most promising idea was also the simplest: a slender pair of forceps that could grab the stone and crush it to smithereens.

Gruithuisen proved the technique was feasible by successfully passing a metal tube into his own bladder, but never used it to treat a patient. Several researchers developed similar devices in succeeding years, but the first to put one to clinical use was a young doctor from Paris. Jean Civiale was still a medical student when he became interested in the problem of bladder stones, and in 1818 he applied to the French government for a grant to fund his work.

Jean Civiale.

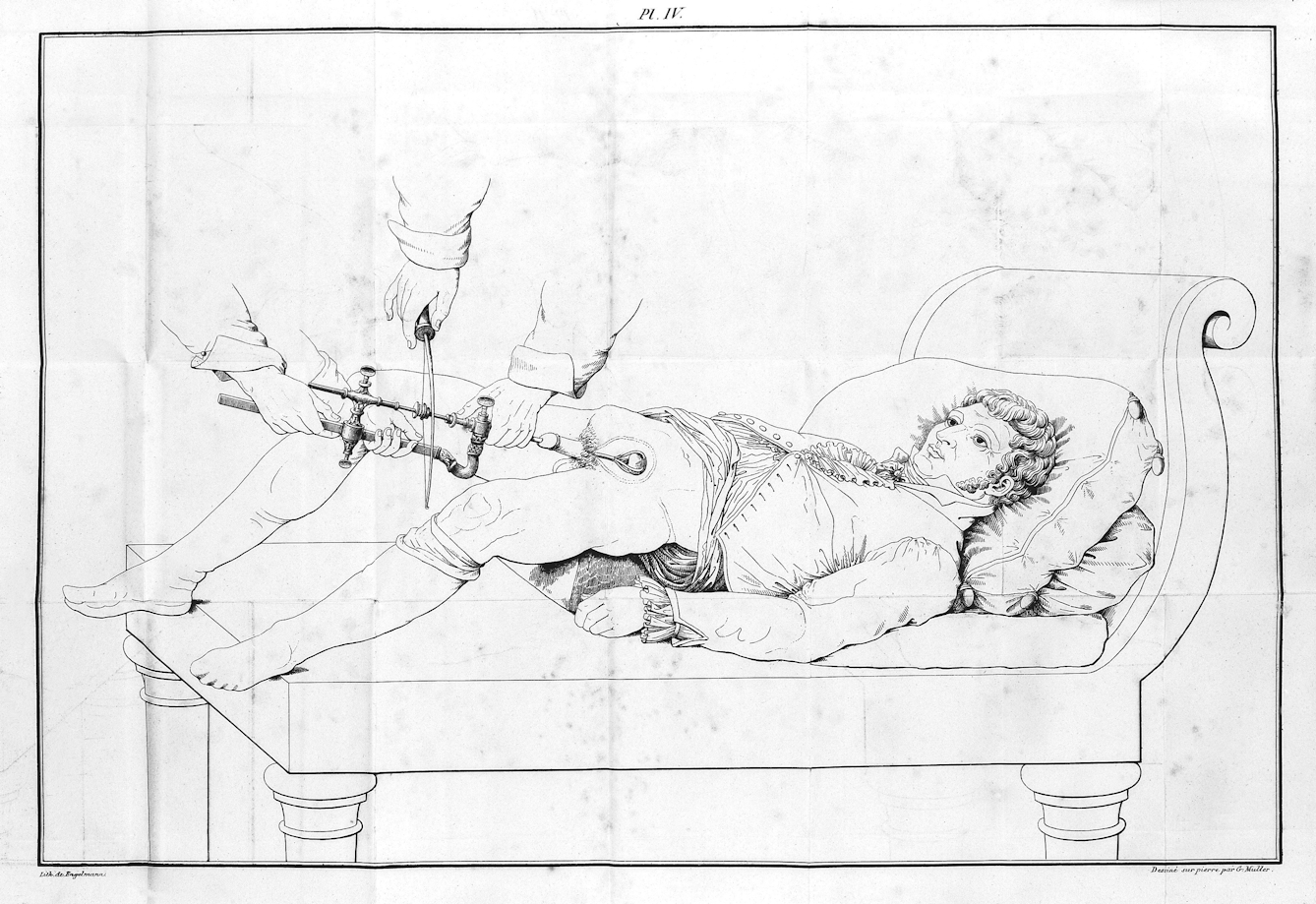

After numerous prototypes he finally designed an instrument he called the lithotriteur – from the Greek words for ‘stone’ and ‘rub’. It consisted of a long, thin metal tube with three grasping arms, like a tiny claw, at the end. This was used to seize the stone inside the bladder; then a drill was passed through the tube to break it up. Catching the stone – which of course the surgeon could not see – required great dexterity. Civiale practised the technique by walking around town with lithotriteur in hand, using it to pick up nuts inside his coat pocket.

An impressive demonstration

Civiale first employed his invention on 13 January 1824, demonstrating it in front of a large audience of eminent medics. The operation took place at his home, and the patient was Monsieur Gentil, a 32-year-old who had suffered from a large bladder stone since the age of four. After removing his trousers and undergarments, Gentil sat down on a small bed.

Civiale then lubricated his lithotriteur with wax and oil, inserted it through the tip of the man’s penis and manipulated it into his bladder. This was an uncomfortable experience for the patient, but infinitely preferable to the agonies of surgery.

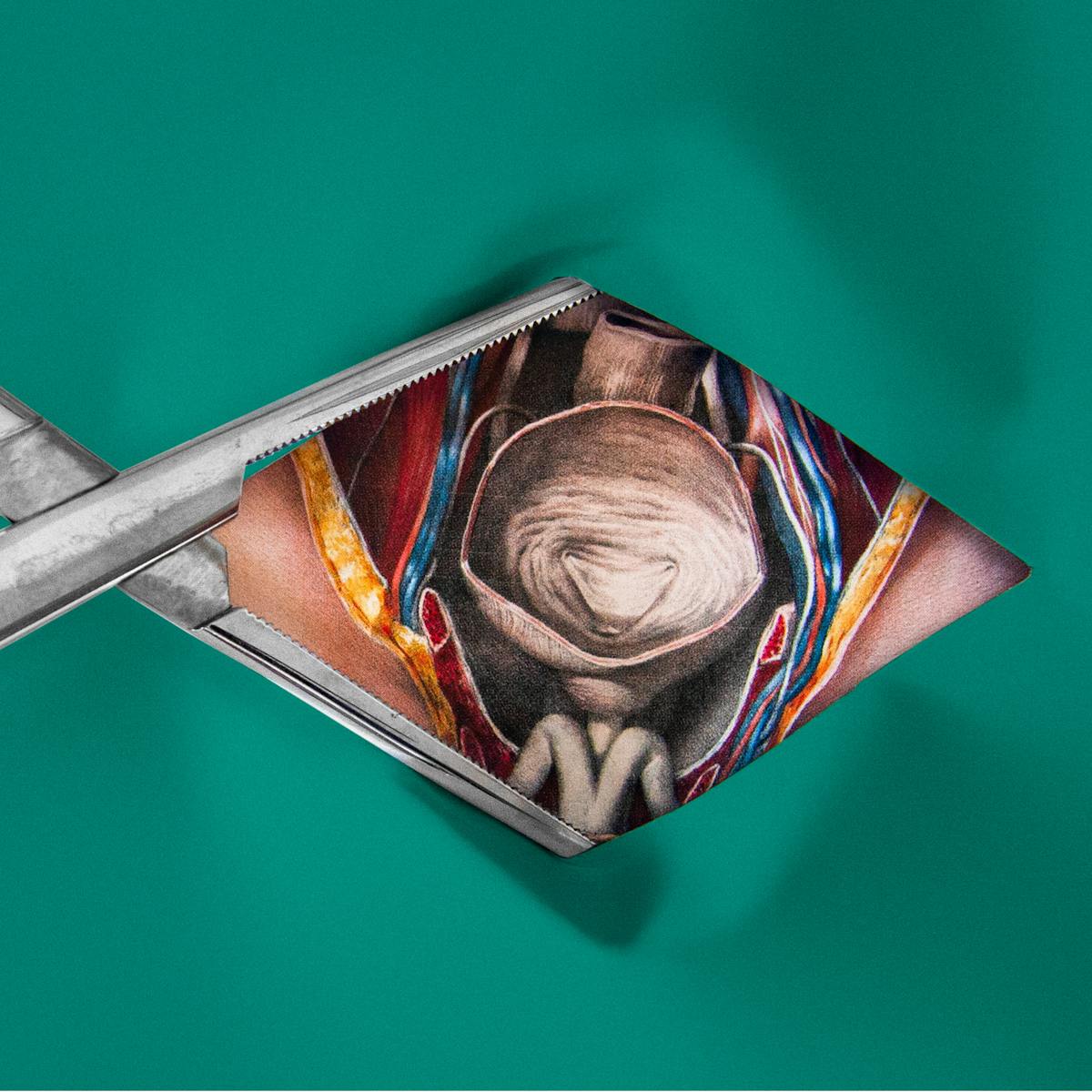

An illustration of Civiale’s lithotriteur in action.

Civiale had no difficulty in grasping the stone with his pincers, and then attacked it with the drill, which struck the stone with a sharp crack that was audible to the spectators. After 40 minutes the job was done, and Civiale flushed the man’s bladder with warm water. When M. Gentil urinated a few minutes later, both surgeon and patient were gratified to find that his urine contained numerous small fragments that had come away from the stone – the instrument had worked.

Two more sessions were necessary to complete the treatment, but three weeks later the object had disappeared, and M. Gentil was cured. “This young man, sick and miserable for so long, became the healthiest and happiest soul alive,” as one witness put it.

The new operation, known as lithotrity or lithotripsy, revolutionised the treatment of bladder stones: within a few decades it became the preferred option for most patients. Other practitioners improved Civiale’s equipment, and it soon became normal to crush the stone rather than drill into it.

Illustration of Jean Civiale’s instruments from ‘Lettres sur la lithotritie’, c.1827.

There were many sceptics, however, and Civiale realised that he needed to prove the superiority of his method over traditional surgery. He painstakingly collated all the data he could find on conventional lithotomies performed all over Europe – more than 5,000 of them. Of these patients almost 20 per cent had died, compared with just 2.3 per cent who had undergone Civiale’s new operation.

His analysis was not particularly rigorous by contemporary standards, but his use of statistics to determine which was the better mode of treatment was far ahead of its time. It foreshadowed today’s evidence-based medicine, in which therapeutic decision-making is influenced more by hard data than by personal experience.

Lithotrity was also the first minimally invasive procedure, representing a new approach to surgery that was less traumatic for the patient, did away with the need for large incisions and involved little or no blood. It was the conceptual ancestor of today’s keyhole operations or the astonishing catheter procedures that now allow cardiologists to operate on the inside of the heart without even putting the patient to sleep.

When Jean Civiale relieved Monsieur Gentil of his bladder stone in 1824, he was not merely demonstrating an ingenious new technique, but also a radically different surgical paradigm.

About the contributors

Thomas Morris

Thomas Morris is author of ‘The Matter of the Heart’ and more recently ‘The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine’. He has worked as a radio producer for the BBC on such programmes as ‘Front Row’, ‘Open Book’ and Melvyn Bragg’s ‘In Our Time’, and his journalism has appeared in publications including the Lancet and the Times.

Emily Evans

Emily Evans is a medical illustrator and anatomist. After her role as a senior demonstrator of anatomy at Cambridge University, alongside her career illustrating medical and surgical books for over a decade, she now writes and publishes books about anatomy and art, such as ‘Anatomy in Black’, while running her brand, Anatomy Boutique.