Unable to imagine a fulfilling future in the violent, strongly patriarchal environment of Mexico City, Laura Morales moved away. Here she describes how she now works to increase awareness of Mexico’s unfolding human rights crisis.

Leaving Mexico and finding refuge in hope

Words by Laura Moralesaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

It was a hot day – rush hour in Mexico City. We were stuck in the normal infernal traffic for that time of day. The car was old, so no air-con, of course. We broke an unwritten rule: we rolled the windows down. A mistake. Two malicious hands entered the car, one through the left window holding a gun, pointed directly at my mother, the other through the right window, holding a knife.

The second hand went for my neck and pressed the knife hard against my jugular. Adrenaline rush, heart pumping hard. In less than a minute the hands left. They left with everything we had: handbag, money, mobile phone and a few pieces of gold jewellery. They also left us feeling vulnerable, violated, afraid.

When I share this story with people in the UK, they are shocked. How is it possible to be robbed at gunpoint in the middle of the day? When I share this story with people in Mexico, they are not surprised; they think we were lucky. It could have been much worse, they say. For most people, it is.

I refuse to be one of the nine women killed every day or one of the sexual violence cases reported every hour to the Mexican authorities

In Mexico, violence of this kind is normal. Violence affects everyone, but women are disproportionately affected. Patriarchy is so rooted within the structure of society that, to many, this violence has become imperceptible. Mexico is a man’s world, in which, too often, women are treated as disposable objects. Sexual discrimination has been internalised to the point that many women believe they deserve the violence they are subjected to. The violence manifests in a number of forms, including physical attacks, verbal abuse, discrimination, rape and murder.

Why did I leave Mexico? Because I wanted to find out what it means to be a woman on my own. I couldn’t imagine a future in which I conformed to the sexist expectations imposed on me by my family and society. I wanted to do something, to have a career and achievements of my own. Back then I didn’t know I was a feminist. Today I know it was my feminist intuition that guided me here.

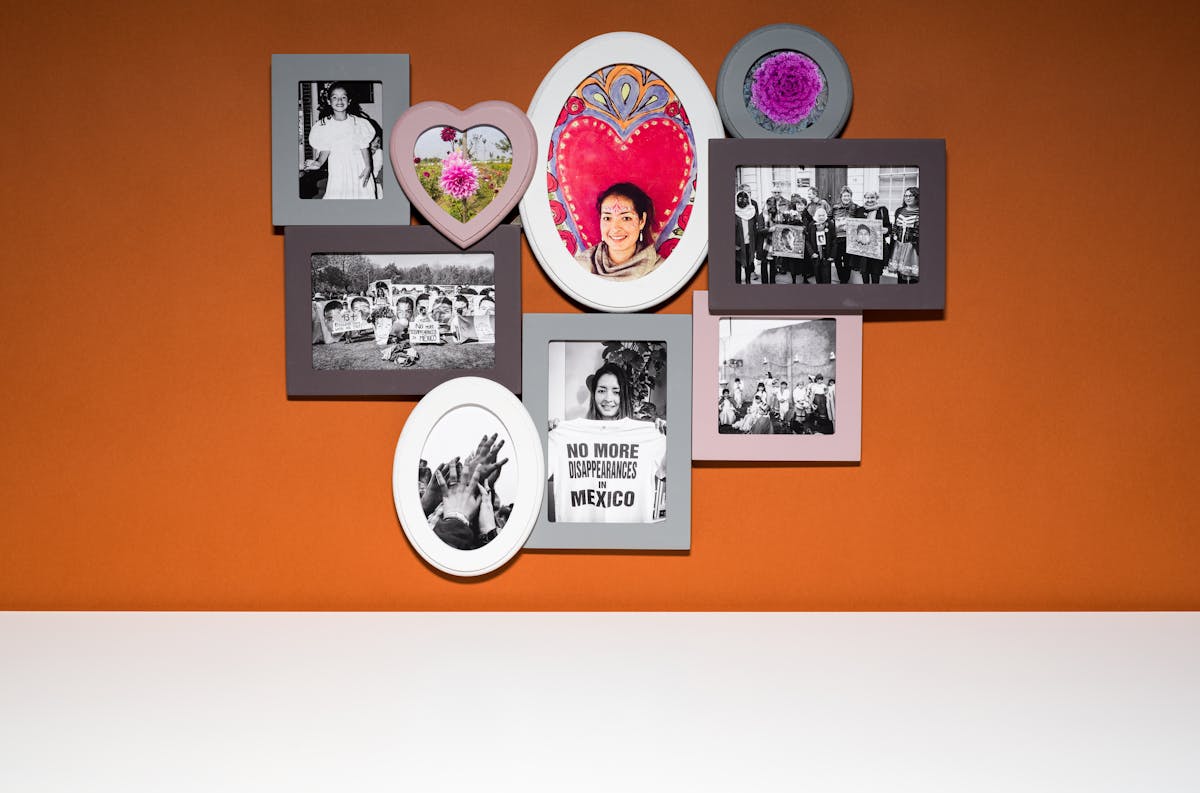

Laura with her friends in Mexico

Why am I still in the UK? Because, since I left, violence against women in Mexico has taken a turn for the worse, and I refuse to be a number. I refuse to be one of the nine women killed every day or one of the sexual violence cases reported every hour to the Mexican authorities. And because I need to speak out, a privilege that in the current circumstances I wouldn’t have in Mexico.

Longing for home

The first few years in London were difficult. I still don’t understand how I made it. I remember that feeling of leaving everything behind. That feeling of not belonging. That deep nostalgia haunting my days and nights. The loneliness. The tears. The desire to give up and fly back home.

Mexico is such a beautiful country. I took its beauty for granted when I was growing up, but I missed it deeply during my first few years here. I missed the people, the smiles, the colours, the smells, the traditions, the food, the weather, the feeling of being Mexican among Mexicans. And the traffic – I even missed the traffic.

Eventually it became easier. A new life – with new friends, habits and hopes – began to grow. Doors opened for me and life became fascinating again. After several years of bouncing from one place to another, I had a stroke of luck. I was employed as an interpreter in a company that works with migrants. I encountered stories full of struggle and came to understand that my suffering was nothing compared to that experienced by many others. Migrating for me was a choice; for many others it’s not.

I loved what I was doing, and, after a few years, I set up my own firm. Becoming an immigration lawyer has deepened my empathy for migrants and their struggles – struggles most people never experience. Many migrants feel betrayed by both countries. The home country they love that couldn’t love them back, denying them the opportunity of a happy, safe and fulfilled life. And the country in which they arrive, which does not truly welcome them, however hard they try. The country in which they will never truly belong.

Helping migrants to fight the barriers imposed on them is such a rewarding thing to do, but it can also be heartbreaking. The hardest part of my job is explaining to couples and families that the strength of their love will not be enough to keep them together, because their income is not high enough. Delivering the pronouncements of an inhumane immigration system leaves me and my clients feeling powerless.

Laura at a protest against the disappearances of Mexicans

Border security and the reduction of net migration have been priorities for recent UK governments, and the system that has been developed has made income one of the main considerations. It has also turned many in society into border officers: employers, doctors, landlords, teachers, among others, are now forced to check the immigration status of migrants before interacting with them. This system and hostile environment brings about a lack of social cohesion and fails to protect vulnerable migrants.

Speaking out

As a migrant, I soon learned that making friends with fellow Mexicans in the UK was often a painful experience. So often they would return home. And every time they left, it felt like a lonely new beginning. To avoid this pain, I eventually stopped befriending Mexicans.

After several years following this strategy, a shared love for our homeland brought a group of Mexican activists together. We all had in common the love for Mexico, the need to speak out, and the intention to remain permanently in the UK. We all wanted to share the stories of those less fortunate back home. We wanted to amplify their voices and draw attention to the suffering they were experiencing.

That is how Justice Mexico Now came about – a small charitable organisation in the UK dedicated to raising awareness about the human rights crisis unfolding in Mexico.

I feel overwhelmed by the admiration expressed by others when I talk about my work. But helping migrants in the UK enables me to give others the opportunities that I was lucky enough to be afforded. And raising my voice for fellow Mexicans suffering back home feels like the least I can do with the privileges I now enjoy.

Helping migrants and fighting for justice is a way in which I find meaning, hope and refuge from all that scares me in this world.

About the author

Laura Morales

Laura Morales is originally from Mexico City but now lives and works in London as an immigration lawyer mainly dealing with the Latin-American community. She is a co-founder and trustee of Justice Mexico Now (JMN), which is a charitable organisation that aims to raise awareness about the human rights crisis in Mexico.