Works by Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery subvert and play with ideas on those most serious of subjects: illness and death. Co-curator George Vasey describes how he honoured their approaches – and added a touch of well-deserved glamour.

Inside the mind of George Vasey, co-curator of Misbehaving Bodies

Words by Gwendolyn Smithphotography by Thomas S G Farnetti

- Interview

On the face of it, ‘Misbehaving Bodies’ may seem a jarringly playful title for a show about chronic illness. But it sums the show up perfectly because in it, Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery use their work to question the authority of the medical establishment and mischievously subvert clichés around illness and death.

“If we’re misbehaving, whose rules are we breaking?” asks curator George Vasey. “That’s the question that art and museums can pose. Misbehaving in this context is about reclaiming something we’ve seen portrayed in a negative way.”

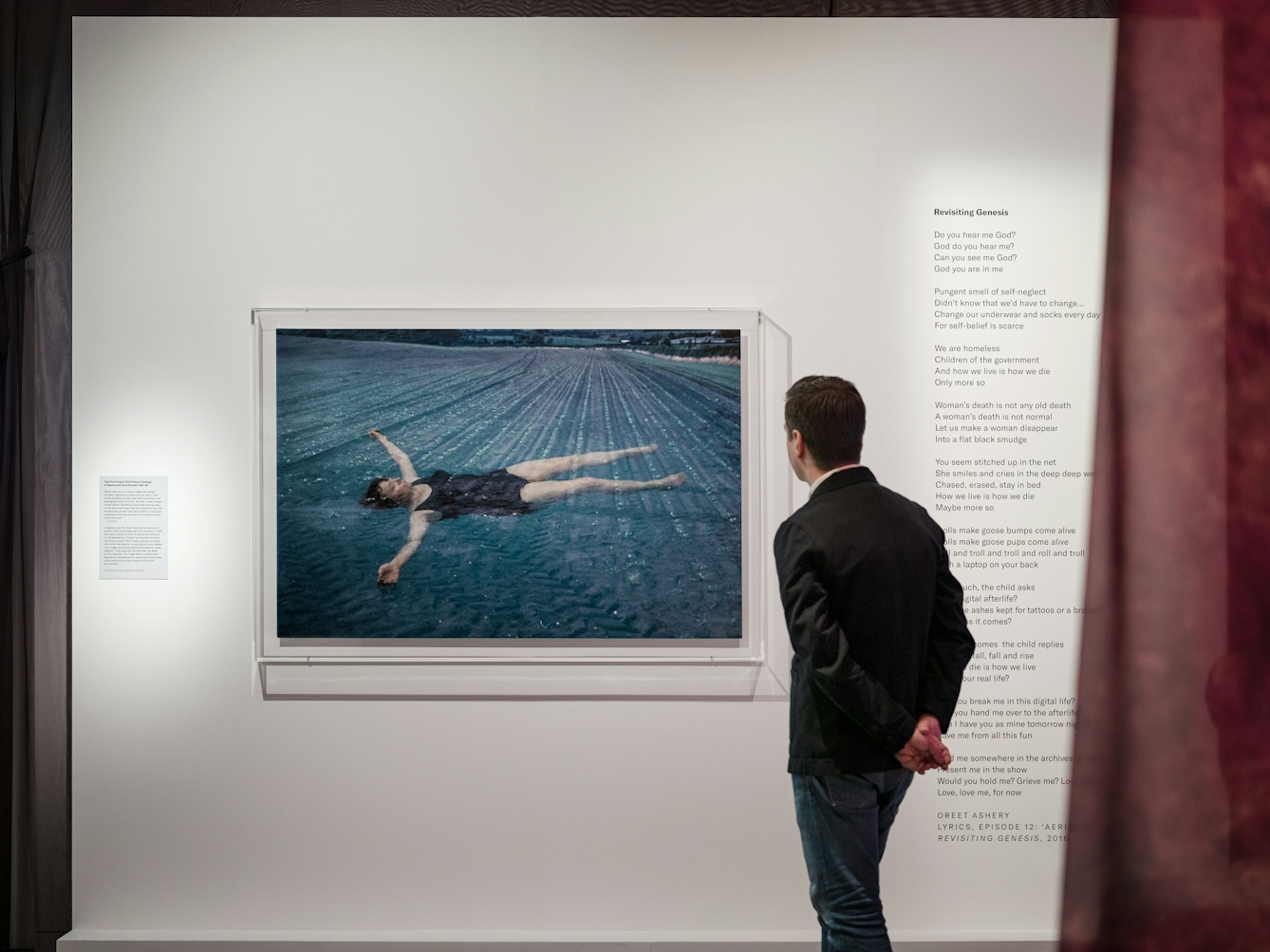

Through text and photography Spence explored having her body treated proprietorially by the medical profession after being diagnosed with cancer in 1982, when she was in her fifties, while contemporary artist Ashery uses her film series ‘Revisiting Genesis’ to look at modern ideas about death.

It didn’t feel right to put my voice into the show.

Understandably, Vasey has been asked about the politics of having a male curator working on an exhibition that is primarily about women’s experiences of illness. “Spence was quite explicit in her will that she didn’t want to be in shows that excluded men. She made much of her work in collaboration with men and through her feminism believed that it was the job of men and women working together to think about patriarchy,” he says.

Nevertheless, it has informed how he’s approached the narration of the show. “I’m not a woman and I’ve never had breast cancer, but I can create space for people with that lived experience to talk on the material. It didn’t feel right to put my voice into the show, it felt more important to bring other people's voices into the conversation.”

In fact, the exhibition was initiated by fellow Wellcome Collection curator Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz before she went on maternity leave and was inspired by the organisation’s purchase of works by Jo Spence.

Collaboration and conversation

Gratifyingly, ‘Misbehaving Bodies’ is a rich polyphony of responses to illness from other artists, people who have been unwell, and healthcare professionals. The guidebook contains a series of round-table discussions about, among other points, how it feels to be diagnosed with cancer, and what healthcare professionals deem to have been the most significant development in cancer care during their career. The latter was the suggestion of the cancer-care charity Maggie’s Centre; experts there said it was essential to get healthcare workers to speak back to the testimony of those living with a diagnosis of cancer.

Getting insight into how medicine has evolved was heartening, says Vasey. “Things are changing; there are developments constantly. It’s not just a conversation stuck in the Eighties.”

While collaborating with Ashery was a conversation, presenting Spence’s photography and scrapbooks came with the uncertainty of working on someone’s estate. “Jo Spence was highly specific about the way her work was shown. A lot of what I’ve been doing is trying to get to know people who worked with her, and trying to embed myself in that era.”

Vasey spoke to her collaborator, Rosy Martin, to try to make sure ‘Misbehaving Bodies’ reflected Spence’s wishes as much as possible. Spence co-founded the Hackney Flashers, a socialist-feminist collective that looked at the representation of women’s labour, both domestic and in the workplace. Speaking to Martin made Vasey realise the importance of foregrounding Spence’s socialist politics.

“Her diagnosis of breast cancer and her work on healthcare was a continuation of her political work, and as such she didn’t want t-shirts with her work on or badges or any merchandise.”

This doesn’t mean the show is spartan, though; Vasey decided to give Spence’s work an overdue shot of glamour. “I wanted the show to look really beautiful and elegant. When Jo was alive she would often show the work in libraries and community centres. There weren’t many galleries showing this kind of work. So when it came into Wellcome Collection I wanted to do it justice.”

But what would she have made of it? “I don’t know, but it felt to me that she would have loved having her name as a mini Hollywood sign. It’s really funny.”

There are other touches of levity, too. The hubs where visitors can watch ‘Revisiting Genesis’ are strewn with soft furnishings, such as a giant teddy bear. “A lot of people are coming into the show and saying it’s not what they expected. Our job is to challenge thinking about health as an institution so it felt important to use humour and playfulness to disarm people.”

While the unusual furniture serves a practical purpose – Vasey wanted to create different ways of sitting in the space – it also links to Spence’s commentary on feeling infantilised by the medical establishment.

Exploring taboos

A scrapbook with a photograph of Prince Charles and Princess Diana on the front that Spence has graffitied with the word ‘CANCER’ is among Vasey’s favourite exhibits. It nods to Spence’s wider interest in Diana: she mentions her in her academic work when discussing the construction of class and gender.

Vasey suggests Diana is also pertinent to Ashery’s work on how our digital life has exacerbated the commercialisation of life and death. “Tony Blair called Diana ‘the people’s princess’, nodding to how she caught a new mood of emotionalism within the public sphere. What social media has done is heightened a demand for an emotionalism. That’s what Oreet’s interested in. The way that the public becomes saturated with the personal, and thus personal narratives become monetised.”

Vasey archived Spence’s work while completing his MA degree, but his link with her is about more than academic history. “Her work deals with being displaced as a child and coming from a working-class background, feeling like a bit of an imposter and dealing with class shame,” he says. “I’d never really seen a photographer articulate that before. That meant so much to me, coming from a similar working-class background.”

The show’s primary aim was to prompt conversations about the taboo subjects of illness and death. But it also has plenty to say about how we live. “The works talk about different forms of marginalisation, from what it means to be a person of colour, to being a migrant, to being working class. As Oreet says in ‘Revisiting Genesis’, how we die is how live, only more so. The economies of marginalisation are amplified in illness. When someone’s poor, they become poorer.”

Ultimately, though, ‘Misbehaving Bodies’ is shot through with a sense of joy and celebration. Both Spence and Ashery look at legacy and what happens after somebody dies rather than seeing death as the final stage.

This is why Vasey chose to highlight ambiguous works such as the final episode in Ashery’s ‘Revisiting Genesis’, which shows a white-suited aerialist on a white background, and an image from Spence’s ‘The Final Project’ depicting her floating body. “They both deal with death, but in a very symbolic and metaphorical way,” he says. “They feel like more of a comma than a full stop.”

This article originally omitted to mention the role of co-curator Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz. It has now been corrected.

About the contributors

Gwendolyn Smith

Gwendolyn Smith is a freelance culture journalist based in London.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.