Over the decades, the development of ways of looking inside the body and at substances taken from the body has helped medics in their quest to alleviate women’s pain. With the cause of her pain still unknown, doctors turn to Jaipreet Virdi’s tests and scans, and diagnosis looms onto the horizon.

Demanding a diagnosis for invisible pain

Words by Jaipreet Virdiartwork by Anne Howesonaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

“When we tell a woman her suffering is normal,” Heba Shaheed writes, “we take away her right to receive treatment for her pain.” I keep these words in mind as I desperately ask doctors for a diagnosis. I am tired of being in pain and eager for an answer.

Another trip to the walk-in clinic resulted in a referral for urgent care in hospital. Another trip to the emergency room, going over my story while clutching my lower left quadrant, the site of my agony. Many more hours staring at blank walls, waiting for the results of CT scans, MRIs, abdominal, pelvic and transvaginal ultrasounds. And more blood tests than I can count.

I’m sent home again and again. I realise that no matter how detailed I make my description of my pain, the doctors don’t touch me. They look at the lab results more than they look at me. The charts tell them all they need – or want? – to know.

The instruments that verify pain

Until the 19th century, patients were experts on their own bodies. When the idea of objectivity emerged as a scientific virtue, images created by machines became more reliable indicators of factual truths, especially when supplemented by scientists’ trained judgement. As bioethicist Daniel Goldberg explains, objective scientific imaging techniques such as the X-ray machine, aided by the stethoscope and photography, not only “rendered previously unseeable injuries seeable”, but enabled medics to “connect the patient’s symptoms to material pathologies in objects that we can image. That’s how we can distinguish truth from falsities.” The doctor seems like a detective, using tools and techniques to augment the senses, and machines to make the invisible visible.

More: Are doctors medical detectives, following leads like Sherlock Holmes?

Microscopy is a useful tool for physicians to understand illnesses, especially illnesses more prevalent in the feminine body, like anaemia. In the 16th century, Johannes Lange described the “the disease of virgins”, chlorosis (anaemia caused by iron deficiency), a disease affecting adolescent girls and indicated by a greenish complexion. Lange attributed the cause to blood trapped in the body and recommended marriage – i.e. sex – as therapy.

Women suffering from chlorosis were the subject of this painting by Sebastià Junyent from 1899. By this point, Andral and other doctors using microscopes had discovered that pregnancy could cause, rather than cure, this condition.

Every approach for dealing with a woman’s discomfort seemed to be solvable by impregnation. It was only two centuries later that French scientist Gabriel Andral examined red blood cells under the microscope, observing that when the cells were destroyed, anaemia was the result. He thus described anaemia as a “decrease in the number of red cells” and argued that though “pregnancy has often been looked upon as a cure... rather [it] disposes some women to the affection while that state lasts.”

The microscope was not only used to investigate blood disorders: it was also used to help understand where women’s pain originated. In 1932, Dr Luther L Hill Jr reported that 1,200 patients between 16 and 61 years of age, whose primary symptoms were pain and abdominal tenderness, were operated on at Touro Infirmary in New Orleans. Hill’s findings – which were not fully understood at the time – when he examined tissue samples from the women indicated endometriosis in 135 of these patients, or 11 per cent of cases. Gynaecologists had misdiagnosed 42 per cent of them.

Developing the golden tool

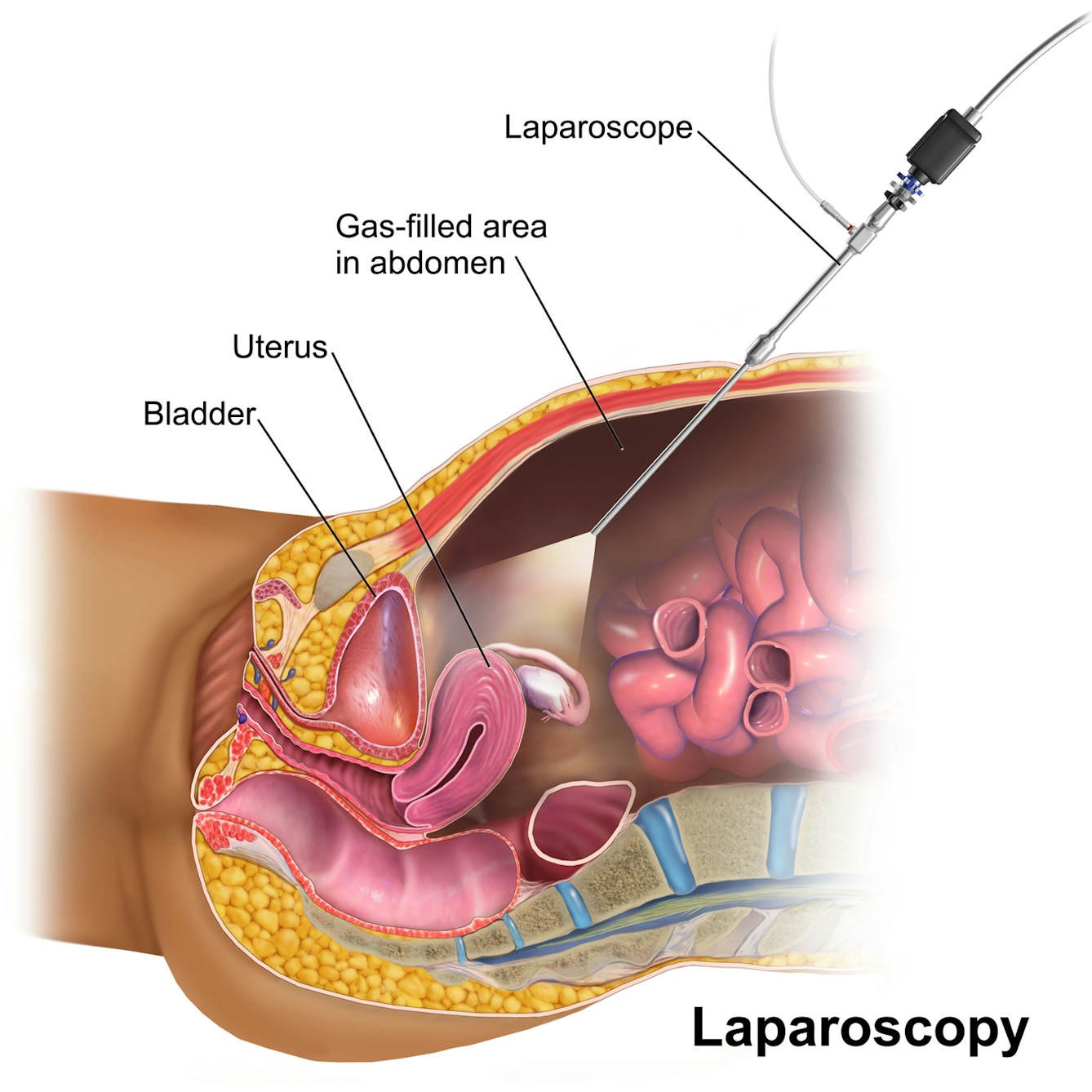

Since most women present with a variety of clinical symptoms, no standard diagnosis was available for endometriosis until the popularisation of laparoscopy in the 1960s. This is a procedure where a scope is inserted through the abdomen to view organs or aid in surgery. In the 19th century, surgeons used lenses, light sources and endoscopes for the procedure, until German surgeon George Kelling introduced the cystoscope in 1901 for animal studies. Swedish surgeon Hans Christian Jacobaeus coined the term ‘laparoscopy’, and further refined the procedure, first on animals, then on clinical patients in 1910.

Nearly 35 years later, in occupied Paris, gynaecologist Raoul Palmer and his wife Elisabeth attempted laparoscopy at the Hôpital Broca in Paris. Facing wartime supply shortages, road blockades and a military curfew, Palmer rode a bicycle to the countryside to gather carbonic acid for generating carbon dioxide (for inflating the abdomen during the procedure, which makes it easier to see the internal organs).

This modern illustration of laparoscopy depicts considerably more modern equipment than that available to Elisabeth and Raoul Palmer in the 1940s.

Limited tools forced the Palmers to be creative: a 4.5-volt torch battery with a rheostat supplied the light source, but the bulbs often broke, meaning they would have to remove the optical system from the abdomen and replace the bulb. Sterile gloves were in limited supply, so the Palmers submerged their hands repeatedly in an alcohol solution.

At the end of the war, Palmer reported more than 250 cases of coelioscopies gynecologiques. His detailed descriptions of his instruments and techniques helped to popularise laparoscopy as an indispensable diagnostic tool and a necessary aspect of gynaecological practice.

Technical improvements continued in the following decades, expanding the range of gynaecological surgery. By the early 1970s, laparoscopy became the ‘golden tool’, the standard for diagnosing endometriosis and evaluating infertility. It was also favoured by patients. As Lisa Michelle Sanmiguel points out in her 2000 PhD dissertation, laparoscopy promised many things: a reduced hospital stay, reduced cost, reduced adhesions and scarring, lower recovery time, less postoperative pain, and no need for follow-up surgery.

I knew something was seriously wrong from the way my body screamed and the way each day was a struggle to survive

I know my body better than the best of them, and constantly argued with doctors about my test results, especially when I felt my case wasn’t demanding serious attention. The more the results were inconclusive, the more frustrated I became. Tired of waiting for a diagnosis, I pushed for a laparoscopy, hoping some answer could be found. I knew something was seriously wrong from the way my body screamed and the way each day was a struggle to survive.

My invisible pain was producing a visible disability. I was exhausted from the anguish, the advocacy, and the gaslighting. I was tired of being told my condition was psychosomatic and tired of the pressures to have babies as ‘therapy’ to anchor my wandering womb and ease my pain.

After months of tests and examinations, I received a preliminary diagnosis of endometriosis. My scans showed multiple fibroids, a polyp, several mysterious nodules, and an 8 or 9 cm mass in my lower abdomen. There it was: this thing, the cause of my agony. I stared at it on my CT scan, shocked at its size. After cancer had been ruled out, a laparoscopy was scheduled. It was time to start treatment.

About the contributors

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.

Anne Howeson

Anne Howeson develops projects concerning place, time and communities. She is a Jerwood Drawing Prize winner with drawings in the collection of the Museum of London, the Guardian News and Media, St George’s Hospital and Imperial College London. She was shortlisted in 2014 for the Derwent Art Prize and the National Open Art Award, and in 2017 for the Ruskin Prize. She has twice been an invited artist with ING Discerning Eye. As a tutor at the Royal College of Art she promotes drawing in all its forms – through process, outcome and as a way of thinking.