First came pain, swiftly followed by efforts to relieve it, as Neanderthal remains reveal. But it was not until the 20th century that scientists attempted to judge pain objectively – and then subjectively, when they came to see that the experience of pain is always personal.

Getting the measure of pain

Words by Jaipreet Virdiartwork by Anne Howesonaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

Everyone has experienced pain: as a fleeting annoyance, temporary injury or chronic agony. It can last a few minutes or a few years. Pain, historian Marcia Meldrum tells us, is the oldest medical problem.

Pain was the reason for my tears, for the rattling of prescription opioids in my bag, for the constant application of the hot-water bottle on my abdomen. It was my struggle and my dismissal. Life became about managing pain, somehow finding a way to live with it, disguising the extent of my agony and passing as ‘normal’. I smiled. I held back tears.

Even as the pain became excruciating, my condition was assessed as non-critical. Medics only saw the pain through charts and scans. The words I uttered to express my agony were their sliding scale for understanding the severity and intensity of my suffering. It was how they measured my pain and determined the strength of the drugs they prescribed.

The power of plants

In 2017, an international team of scientists used DNA analysis to examine the skull of a Neanderthal from the archaeological site El Sidrón in northern Spain. The skull had a visible dental abscess on the jawbone, and the scientists discovered traces of poplar, which contains salicylic acid and a natural antibiotic mould, evidence that this Neanderthal relied on plants with pain-relieving properties to medicate himself.

Humans too, have relied on plants and other natural treatments for relieving pain. Six thousand years ago, Mesopotamians (from an area now mostly in Iraq) used willow bark for fever. In the centuries that followed, other plants were used for medicinal purposes, including turmeric, coca leaves, cloves, valerian, ginger, eucalyptus and the opium poppy. Some cultures devised techniques for pain relief: trepanning, Reiki, acupuncture and leeching. Drug preparations, such as laudanum, headache powders and other forms of patent pills could also be purchased for self-medication.

Harvesting opium poppies – the source of pain-relieving morphine – in the 18th century.

As historian Joanna Bourke writes, the invention and proliferation of anaesthetics in the 19th century “resulted in dramatic shifts in the experience of pain”, but these shifts “have not been universal”. Physicians used anaesthetic agents – such as chloroform and ether – judiciously on patients, but these substances were unregulated, resulting in sometimes dangerous consequences.

Of all natural pain relievers, perhaps none was more ubiquitous than opium. Easy to obtain and extract, it provided both relief from pain and pleasurable sleep. But it was also unpredictable in quality, leading chemists to isolate the active ingredient from the resinous gum secreted by the opium poppy in the hope of delivering a safe, effective and reliable analgesic. The active substance – morphine – was ten times more powerful than processed opium.

By the mid-1800s, morphine was widely available in standardised doses, especially after the invention of the hypodermic needle. For soldiers injured in the American Civil War, morphine was their lifesaver. It was touted as a cure for pain, disease and even alcohol and opium addiction. It was also highly addictive, and synthetic opiates – such as codeine, heroin and methadone, the first of which was developed in the 1830s – were just as dangerous, especially when addiction increased tolerance.

‘Objectively’ measuring pain

The rise of opiate addiction prompted medics to ask: who really needs medicine for their pain, and how can we tell? Is there a way to quantify the intensity of pain, to objectively measure it using scientific devices?

In the 1940s, James Hardy, Helen Goodell, and Harold G. Wolff, doctors at the University of Cornell, devised a method of quantifying pain thresholds using a machine they called the dolorimeter. The device focused light on part of a person’s forehead – which had been blackened with ink to rule out differences in skin colour – to produce a painful stimulus up to 113ºF/45ºC.

The moment the subject said “ouch” was the pain sensation threshold, and the moment they turned away from the light was the pain tolerance threshold. The difference between the two thresholds became the unit of measurement, what the researchers called a ‘dol’ – based on dolor, the Latin word for pain.

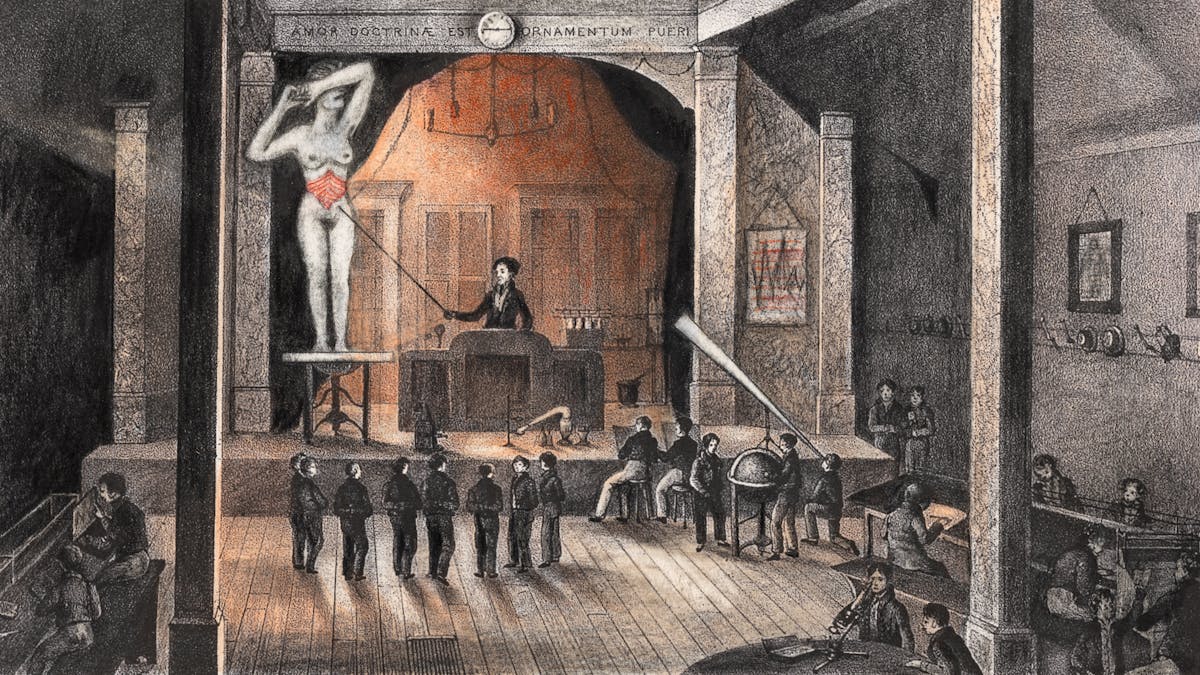

Various devices have been designed to try and measure pain. The retractable needle in this algometer tests very fine sensitivity to pain or touch. The needle is inserted into the skin until a specific pain response is given.

The researchers conducted further studies on 70 medical students and 13 women in labour, who were subjected to the dolorimeter in between contractions. The data enabled them to create a 0 to 10.5 dol scale, with 8 dols the point at which second-degree burns were formed. Dolorimetry thus “made it possible to obtain reliable estimates of spontaneous and experimentally induced pain intensity”, as Hardy claimed.

People in pain, however, cannot always separate the intensity of pain from the type of pain.

In 1959, anaesthetics specialist Dr Henry Beecher refuted dolorimetry and the notion that pain could be objectively measured. His claim was based on his work on placebos in double-blind and randomised studies, and on his experiences during World War II.

At the Battle of Anzio, he noticed battlefield causalities had less intense pain and thus required less morphine than civilian counterparts. Soldiers, Beecher realised, were grateful to survive and thus reported less pain. He concluded that pain is subjective, for “the intensity of suffering is largely determined by what the pain means to the patient”,

The personal nature of pain

Beecher’s work transformed analgesic research. Pain came to be understood as an experience only the sufferer can describe, commonly by using a visual analogue scale (VAS): a one-dimensional tool about 10 cm in length with a continuous line anchored by pain descriptors ranging in intensity. The scale is marked from 0 to 10, with 0 referring to “no pain”, and 10 as the “worst pain imaginable”.

Pain came to be understood as an experience only the sufferer can describe.

The VAS provides medics with approximations for determining the severity of a patient’s pain and which drugs to use to alleviate that pain. In clinical settings, it is intuitive and simple to administer. Yet pain is a multidimensional experience that is frequently guided by other factors, including emotions, sensitivity and tolerance, which can complicate clinicians’ efforts to assess and reduce pain into numbers. Attempts to communicate pain often result in a two-sided struggle.

Zero to 10 could not always convey what I felt. As a historian of medicine, I was aware of how subjective experiences of health are often dismissed in favour of the medics’ more objective stance. I made sure my medical files had a note mentioning that I was a historian, if only to assert my authority for my pain to be taken seriously.

In front of hospital staff, I found I was policing myself. I lied about where I fell on the VAS, negotiating with myself over when to exaggerate in order to be taken seriously and when to suppress my pain so the medics wouldn’t perceive me as a drug-seeker. I got used to coaxing suffering into silence.

One day my partner turned to me and said, “Scream. Scream as loud as you can. Let them hear your pain.”

About the contributors

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.

Anne Howeson

Anne Howeson develops projects concerning place, time and communities. She is a Jerwood Drawing Prize winner with drawings in the collection of the Museum of London, the Guardian News and Media, St George’s Hospital and Imperial College London. She was shortlisted in 2014 for the Derwent Art Prize and the National Open Art Award, and in 2017 for the Ruskin Prize. She has twice been an invited artist with ING Discerning Eye. As a tutor at the Royal College of Art she promotes drawing in all its forms – through process, outcome and as a way of thinking.