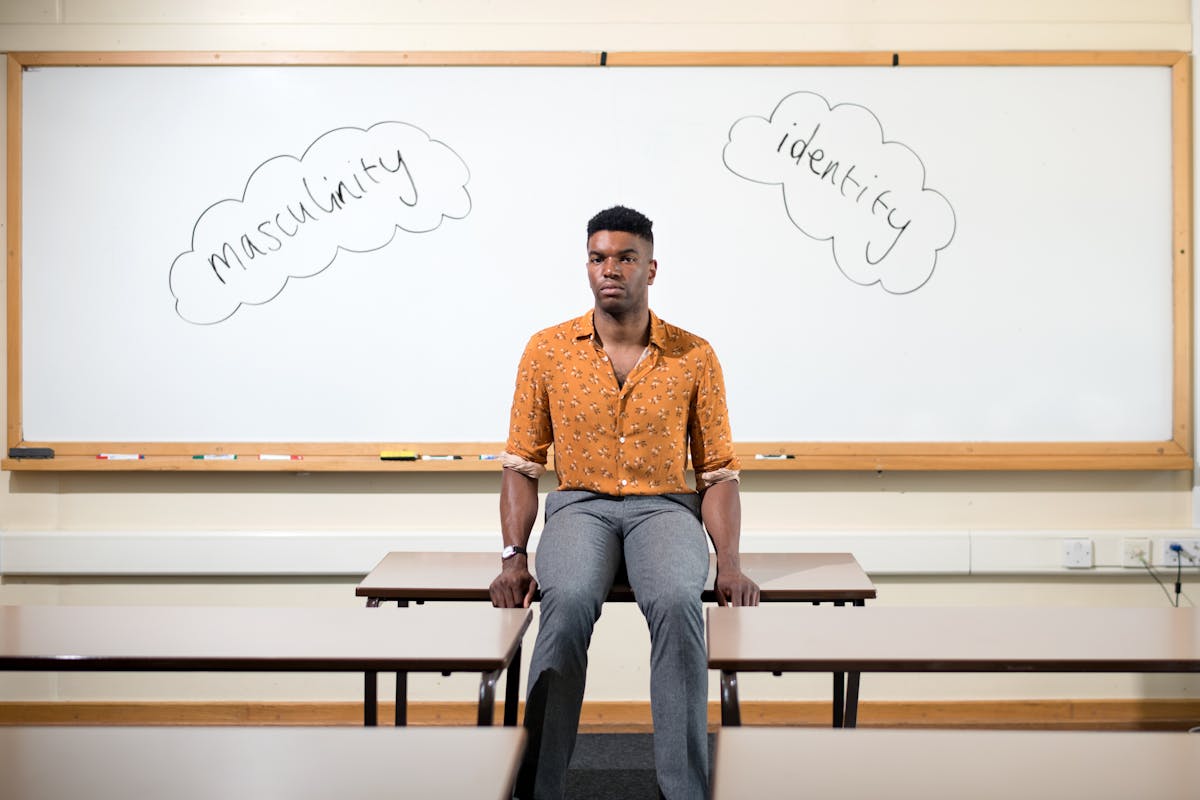

In the world of classroom politics, asserting your identity and authority as a teacher is paramount. Hoping to add a little variety to the narrow range of role models his students usually come across, writer and teacher Okechukwu Nzelu decides to break the mould by simply being himself.

Confronting male stereotypes in the classroom

Words by Okechukwu Nzeluphotography by Robin Hammondaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

“Sir! Sir! Sir!”

The year is 2014: my first year as a high-school English teacher.

The student who is calling out (I’m still working on the whole ‘hands-up’ thing) has an urgency in his voice, but he could be asking about anything. It could be a medical emergency, or he could just be telling me a knock-knock joke.

I take a breath. “Hi there. What’s up?”

“Sir! What team do you support?”

I freeze. I dread this question.

We live in Manchester, a football city, so there’s no right answer. You’re either a ‘glory supporter’ (United) or a sell-out (City) or a weirdo (me). And make no mistake, this is a Man Thing: if you don’t follow football, you run the risk of being confined to that unfortunate substrata of unthreatening but not-quite-normal men, like trainspotters and men who haven’t seen ‘The Matrix’.

So should I lie? Again?

I look at the boy for a moment, and decide.

Breaking the mould

I love teaching. There’s no other job so varied, so challenging, so rewarding. I especially love being able to teach my students about the world through our discussions of the writers whose work I teach: learning how other people think and live is part of any education, especially a literary one.

And it’s more than that: as a black man in a society that too often portrays black men as just a few narrow stereotypes, I am in a position that enables me to quietly model what it is to be male, and black, and scholarly. To be male and black and gentle; to be male and black and emotionally articulate. This is a valuable thing.

But, as almost any black person will tell you, it’s not always easy to break the mould. People make assumptions, people have inherited prejudices, people are taught certain preconceptions. I don’t always fit with those. I can’t explain the offside rule and I’m always a little nervous that one day, I’ll be exposed for the fraud I am.

More: What information on sex and sexuality is available in the classroom?

Boys, though, don’t always fit the stereotype, either. When I was training, a lot of people told me that they prefer teaching boys to girls because “boys don’t hold grudges if you tell them off” (not true) and that “boys aren’t moody like girls” (definitely not true). Every student is different and, while social conditioning is definitely a thing, I think it’s easy to see your assumptions reflected back at you, if that’s all you expect to see. There are girls who don’t ever get ‘moody’; there are boys who cry. There are boys who, like me, don’t particularly care about football.

So why should I lie?

Like many teachers, I have a persona: a kind of balance between how children see me and who I really am. Around my students, I become someone who insists everyone has a working pen, really cares about ‘hands-up’, waits for silence, glares occasionally. It’s not quite deception; it’s a kind of acting that allows me to create the right environment.

But if someone pulls the wrong thread – asks the wrong question – any persona can come undone. Just being asked who I support makes my blood run cold with fear, because what if it’s not just a question? What if it’s more? What if the student has intuited, somehow, that I’m not quite what he expected a black male teacher to be? Why does Mr Nzelu like reading? Why does he wear floral ties to work? And what’s with that squeaky voice?

But… why should I lie? If asked this question in any other context, I’d shrug and tell the truth. When, after a brief moment, I shakily confess the truth in the classroom, my student looks at me strangely for a moment, then turns away, surprised and mildly disappointed, to talk to a friend.

Problem selving

The following year – new school, new colleagues, new students – I am a little older, and a little better at my job. Still, I confide in a friend at work that sometimes I worry about this aspect of my teaching.

“I’m not laddy. I’m not into football. And I’ve got that squeaky voice…”

“But don’t you think it might be good for them to see a variety of male role models?”

I think for a moment. Maybe she’s right. I would have loved to have had that when I was younger.

Today, I am grateful that many students feel more able to be themselves in school, whether or not they fit in. Once, a student shared with me his knowledge of optimum protein-shake consumption. One student told me he wanted to be a pilot so he could fly his family across the world. Two students told me how excited they were to attend the launch of a book by their favourite YouTuber. One student told me all about the models he constructs from his 3D printer and paints in his spare time.

My student looks at me strangely for a moment, then turns away, surprised and mildly disappointed.

The 19th-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins was fascinated with the idea of things being themselves. He called it ‘selving’. In the poem ‘As Kingfishers Catch Fire’, he writes:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

Manley Hopkins suffered repression in his lifetime, so it is interesting that his poetry is characterised by a fascination with the glorious things that happen when anything simply is itself.

So why should I lie? What if the best teachers can be themselves — the best of themselves — to bring out the best in their students? What if the best teachers allow their students to be the most inquisitive, the kindest, most diligent version of who that individual is or might be? The version who loves to paint figurines, who plays rugby, who wants to fly.

A student’s opinion

“Sir? I want to tell you something but I’m not sure if it’s a bit rude…”

I pause. The year is 2015: I am in my second year of teaching and I am chatting to some students during form time. I notice the student is grinning mischievously.

“Well,” I smile cautiously, “you’re a very polite, mature girl, so I’m sure you can find a way to say it politely and appropriately.”

She giggles. “Sir,” she says. “You’re kind of… sassy.”

A moment’s silence, and then we both laugh. “I think,” I say, “I’ll take that as a compliment.”

About the contributors

Okechukwu Nzelu

Okechukwu Nzelu is a teacher and writer based in Manchester. In 2015 he was the recipient of a Northern Writer’s Award. His first novel, ‘The Private Joys of Nnenna Maloney’, will be published in October 2019 by Dialogue Books.

Robin Hammond

Robin Hammond has dedicated his career to amplifying narratives of marginalised groups through long-term photographic projects and is the winner of many prizes. His work on discrimination against the LGBTQI+ community around the world, ‘Where Love Is Illegal’, has been featured in publications including Time Magazine and National Geographic. Robin is the founder of Witness Change, a non-profit organisation dedicated to advancing human rights through visual storytelling.