It’s tempting to diagnose famous figures from the past using modern definitions of mental health conditions. But without a fuller picture in the person’s own words, revealing what they thought and felt, the retrospective psychologist is on shaky ground.

I suffer from OCD, a hugely misunderstood and trivialised psychiatric condition, as well as periods of severe depression, and I understand the desire to seek past figures with whom to identify. It can be comforting to know that your suffering has a history. But we tend to make assumptions about historical figures, who in fact inhabited very different mental worlds from our own.

In ‘Diagnosing the Past’, I introduced the pitfalls of retrospectively diagnosing diseases from written sources. Here, I will examine the diagnosis of mental disorders in the past – ‘retrospective psychiatry’ – using the modern classification ‘obsessive compulsive disorder’ (OCD) as a case study.

The problem of retrospective psychiatry

In the 1520s Ignatius of Loyola, the Spanish theologian and founder of the Jesuits, produced his ‘Spiritual Exercises’, a work of prayers and meditations to guide those undertaking religious retreats on their spiritual path. In this, Ignatius wrote: “After I have stepped on that cross, or after I have thought or said or done some other thing, there comes to me a thought from without that I have sinned, and on the other hand it appears to me that I have not sinned; still I feel disturbance in this; that is to say, in as much as I doubt and in as much as I do not doubt.”

Some people see this as evidence that Loyola suffered from OCD. But taking evidence written in a specific context and for a certain purpose to make a medical diagnosis flattens out the interesting aspects of the suffering of individuals in their own contexts.

Retrospective psychiatry sprang out of an Enlightenment ideal to replace ‘religious’ explanations with ‘scientific’ ones. It is an interesting phenomenon in psychiatry’s development, but ultimately tells us more about the psychologists doing the diagnosing than any of their historical subjects.

Mental disorders are without doubt the most difficult conditions to retrospectively diagnose. There is, at present, no way to gather physical evidence (from bones or other physical remains) for modern mental disorders. And writers noting down which behaviours were considered abnormal or deviant depends on societal context.

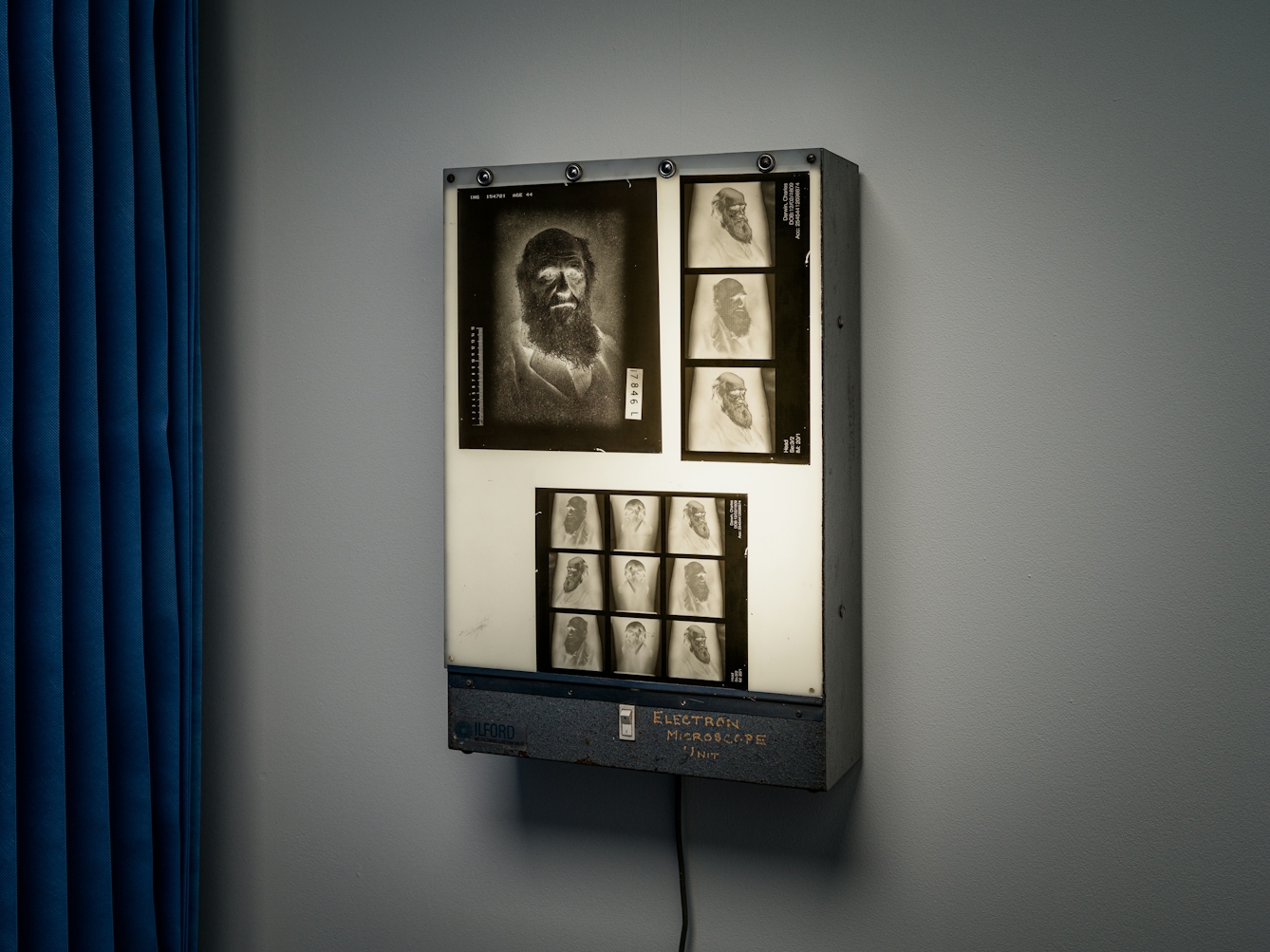

Charles Darwin suffered throughout his life with a variety of mental and physical symptoms, including obsessive thoughts about his and his children’s health.

Additionally, much less is understood about psychiatric illnesses than physical disorders even in the present day: if our modern categories are prone to change – the medical guidelines are updated every few years, after all – then it is even harder to apply them to people in the past.

Madness did not always equal illness in the way we understand it today. What we might interpret now as mental distress might, centuries ago, have been a way to prove saintliness or demonic possession. It could have resulted from a superfluity of humours, an excess of study, a lack of sex, or it could be the consequence of Divine punishment.

More: Read about how confession was considered good for your health in the medieval period.

Also, because much of the written evidence we have about past figures was not committed to paper by those people themselves, we don’t know how they actually felt, which is crucial in the modern diagnostic process. Diagnosis now involves a dialogue between doctor and patient, recording how the patient thinks and feels in their own words.

Armchair psychiatry isn’t just a problem for long-dead subjects: it has officially been deemed unethical for psychiatrists in the present day to speculate about the mental condition of a notable living figure they have not examined in person. So taking a step even further away and diagnosing a person who existed in a completely different time and place is even more fraught with complications.

A condition that eats up time

In the media, OCD is often trivialised as a perfectionist quirk that might make a character clean a lot or continually flick light switches. In reality, OCD is a serious and debilitating – but highly treatable – anxiety disorder. It is an extremely distressing and time-consuming condition that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with being orderly or clean.

OCD can be diagnosed when a person has both obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges or impulses that are experienced as intrusive and unwanted, and usually cause anxiety or distress. An obsessional worry could be: “What if I have contaminated that person simply by touching them?” Questions tend to begin with “what if?” and are impossible to answer with complete certainty. The person experiencing them attempts to ignore or suppress them or tries to neutralise them with some other thought or action, such as a compulsion.

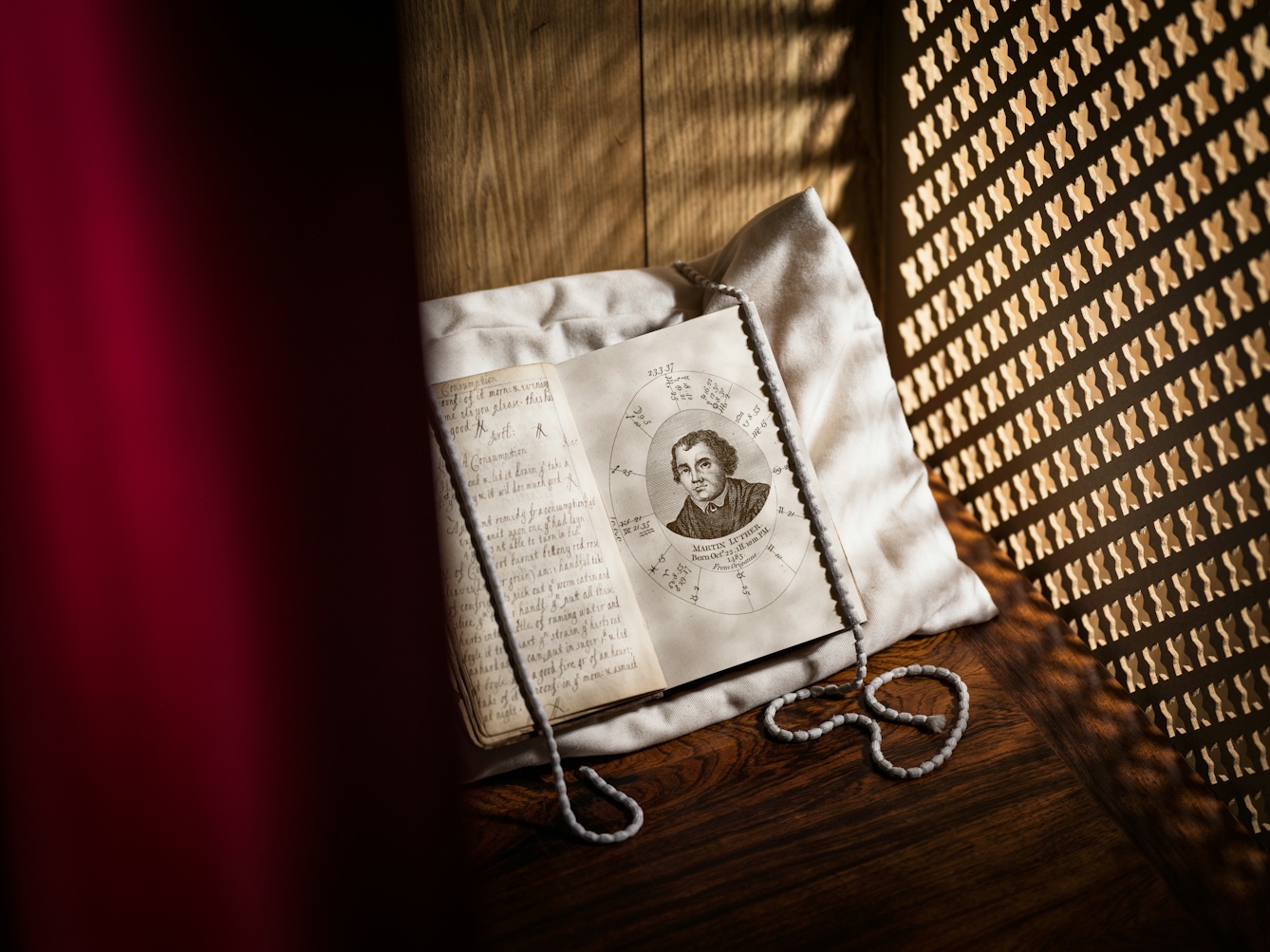

Martin Luther was said to have experienced ‘obsessive scrupulosity’ and ‘compulsive confessing’.

Compulsions are the repetitive actions we take to try and alleviate the worry, and might include hand-washing, ordering or checking, or mental acts such as praying, counting or repeating words silently. A person performing a compulsion is responding to an obsession, and does it according to their own rigid rules.

A person with OCD believes that performing a behaviour or mental act will reduce anxiety or distress, or prevent some dreaded event or situation. But compulsions are not connected in a realistic way with what they are designed to neutralise or prevent, or are clearly excessive. Sadly, compulsions simply fuel obsessions by providing short-term relief without a long-term solution.

Is scrupulosity a type of OCD?

Sometimes seen as a predecessor of OCD, scrupulosity is an intense preoccupation with moral or religious matters. The first known public description of scrupulosity occurred in 1691 in a sermon by Bishop of Norwich, John Moore. Moore called it “religious melancholy”, and described sufferers as having: “… a flatness in their minds ... which makes them fear, that what they do, is so defective and unfit to be presented unto God, that he will not accept it ... They experience naughty, and sometimes Blasphemous Thoughts which start in their Minds, while they are exercised in the Worship of God ... despite all their endeavours to stifle and suppress them ... The more they struggle with them, the more they increase.”

This sounds like OCD: a cycle of obsessional questioning and compulsive attempts to push the thoughts away, leading to a worsening of the problem.

So does it make sense to map OCD onto religious melancholy? Put simply, no. The quote above cherry-picks the parts that fit the argument for OCD from a much longer, more complex work.

People with OCD can of course experience obsessive religious thoughts, but that doesn’t mean that religious melancholy was OCD. What Moore described was a religious and moral issue, with a religious solution, specific to the beliefs prevalent at the time. The modern diagnosis of OCD is an anxiety disorder with a behavioural and often medical solution – the treatments with the best evidence base are cognitive behavioural therapy with exposure and response prevention, and sometimes medication such as SSRIs.

Diagnosing famous figures from history

Martin Luther (1483–1546), a key player in the Protestant Reformation, is one of those retrospectively diagnosed with OCD. In 1958, psychologist Erik Erikson wrote ‘Young Man Luther’, diagnosing Luther with, among other things, “obsessive scrupulosity” and “compulsive confessing”. Much of Erikson’s evidence didn’t come from Luther himself, though: his conclusion rested heavily on the writings of Luther’s protégé, Philipp Melanchthon. For example, Melanchthon stated:

“often when contemplating the wrath of God, as exhibited in striking instances of His avenging hand, suddenly such terrors have overwhelmed [Luther’s] mind, as almost to deprive him of consciousness; and I myself have seen him whilst engaged in some doctrinal discussion, involuntarily affected in this manner, when he has thrown himself on a bed in an adjoining room, and repeatedly mingled with his prayers the following passage ‘God has concluded them all in unbelief that he might have mercy upon all.’”

Luther’s fear for his own salvation and repetition of prayers and mantras have been taken as evidence for a diagnosis of scrupulosity by some, but this alone isn’t enough to make a firm diagnosis: and this key piece of evidence does not come from Luther himself.

Writer John Bunyan (1628–88) is another candidate. Several 19th-century psychologists examined his life and works, and diagnosed him with a range of mental pathologies, including scrupulosity. This was most recently emphasised in Christian psychiatrist Ian Osborn’s 2008 book ‘Can Christianity Cure Obsessive Compulsive Disorder?’. But, as Paul Cefalu, Head of English at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, pointed out in 2010, “although early modern theologians do manifest scrupulosity, such religiosity was a culturally acceptable, even recommended component of spiritual progress, a necessary means of receiving an unmerited bestowal of God’s grace.”

Exaggerating these parts of Luther and Bunyan’s characters, then, would have been a way of emphasising their sanctity and piety; and, crucially, their suffering was regarded as positive.

Samuel Johnson, according to his author James Boswell, had tics such as skipping over cracks in the pavement.

Samuel Johnson (1709–84), the polymath most famous for his dictionary of 1755, has been retrospectively diagnosed with both OCD and Tourette’s syndrome (the two often occur together). The evidence presented for this diagnosis comes almost solely from ‘The Life of Samuel Johnson’ by James Boswell, published in 1791. Boswell followed Johnson around, making copious notes, so we have good evidence of Johnson’s outward compulsions and tics: skipping over cracks in the pavement and touching doorknobs.

But we have very little autobiographical material revealing how Johnson felt and thought. What is presented as evidence in his own words is either from prayers or novels that he wrote (which are hardly representative of an author’s true feelings), or reported speech via Boswell. So it would be unfair to Johnson to assume that his tics were a reaction to obsessive thoughts.

Charles Darwin (1809–82) suffered throughout his life with a variety of mental and physical symptoms. Keen to pinpoint the explanation, various scholars have retrospectively diagnosed him with OCD, as well as Asperger’s syndrome, panic disorder with agoraphobia, and psychosomatic illness. So there is hardly a consensus as to what caused these multiple issues.

However, we do know from Darwin’s own words that he suffered with obsessive thoughts about his and his children’s health, and displayed what could be called compulsions: reassurance-seeking from others, repeating mantras, and checking behaviours. But Darwin was very much a product of his own time and place. A much better question to ask than “Did Darwin have OCD?” is “How did Darwin and those around him conceive of and deal with his suffering?”

The most important point to make in conclusion is that these individuals (and many others in the past) suffered greatly with whatever afflicted them: Luther and Bunyan’s tortured worry over their salvation, Johnson’s tics, Darwin’s health fears. For me – someone who has been through intense periods of mental suffering in the present day – that is enough with which to identify.

For more information or advice on OCD please contact OCD Action or OCD-UK.

About the contributors

Joanne Edge

Dr Joanne Edge is a historian who specialises in late-medieval and early modern European social and cultural history, with an emphasis on medicine and the ‘occult’ sciences: divination, magic and astrology. She has previously worked as Assistant Editor on the Wellcome-funded Casebooks Project at the University of Cambridge and is currently Latin Manuscripts Cataloguer at the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester. Her first book, ‘Numerological Divination in Late Medieval England’, is under contract with Boydell and Brewer.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.