During the bubonic plague epidemic of 1665–6, the residents of Eyam in Derbyshire quarantined themselves within the village boundaries to help prevent the disease spreading further. Simon Norfolk revisits the village to tell the story of this small community’s remarkable sacrifice and the genetic discovery that came from those who survived.

In pictures

Each year on ‘Plague Sunday’, at the end of August, residents of Eyam in Derbyshire in the north of England mark the bubonic plague epidemic that devastated their small rural community in the years 1665–6. They wear the traditional costume of the day and attend a memorial service to remember how half the village sacrificed themselves to avoid spreading the disease further. This photograph shows Eyam Museum staff on the steps of Eyam Hall.

A stained-glass window in the local church of St Lawrence documents the onset of the plague. At the end of August 1665, as the plague raged through London, 150 miles to the south, a consignment of fabric was sent from the capital to a tailor in Eyam. Contained in the bale of damp cloth were fleas carrying plague. The tailor’s assistant, George Viccars, received the bundle and set the cloth out to dry by the fire. After a raging fever, Viccars died on 7 September 1665, and more began dying in the household and immediate neighbourhood soon after.

The frequency of plague deaths fell as the winter of 1665 drew in, but by the following summer, the death rate accelerated. August 1666 saw the highest number of victims, peaking at eight deaths in a single day. The Riley Graves, a walled enclosure on the outskirts of the village, holds the bodies of Elizabeth Hancock’s husband and six children, all of whom died within eight days of each other. Because of the high risk of infecting her neighbours, she had the traumatic task of dragging the bodies from her farmhouse and burying them herself.

As the epidemic spread and those with the means fled, the remaining villagers turned to their rector, the Rev. William Mompesson, and Puritan minister Thomas Stanley. To prevent the disease spreading to neighbouring parishes and beyond, Mompesson and Stanley successfully persuaded the villagers to quarantine Eyam from the outside world. The chair believed to have been used by Mompesson during his crucial meetings with Stanley is now kept to the left of the altar in St Lawrence’s church in Eyam.

After a year, plague was still claiming its victims, and on 25 August 1666 Catherine Mompesson, wife of the rector, finally succumbed and was buried in the church graveyard. On the east face of the tomb, a badly weathered inscription reads MORS MIHI LUCRUM, which translates loosely as “death is my reward”. Today, on the last Sunday of August each year, a rose-entwined wreath is placed on her tabletop grave as part of the Plague Sunday commemoration.

People were unsure of the causes of bubonic plague: ‘miasma’ or bad air was the best guess, but close contact between people was also thought to be a risk. Mompesson and Stanley thought that holding church services in the open air would minimise the spread of contagion. Mompesson held Sunday services just south of Eyam at Cucklett Delf, preaching to the congregation from a natural arch of rock that came to be known as Cucklett Church.

Most older houses in Eyam bear plaques enumerating those who died in each house. Humphrey Merrill, the village herbalist, lived in this house, and died here on 9 September 1666. His wife Anne survived. Andrew Merrill also lived here, and survived the plague by going to the edge of Eyam Moor and building a crude hut in which he lived with his pet cockerel until the plague was over.

The story of Eyam and the tumultuous events of 1665–6 are retold today in the local museum. The ‘Plague Doctor’ exhibited there is modelled on an early-17th-century Parisian physician, who was paid by the town to treat the afflicted. A beak-like mask, stuffed with herbs, straw and spices was designed to protect him from putrid air, which (according to the miasmatic theory of disease) was seen as the cause of infection. Symptoms were treated with curious methods, such as fastening a toad to sores in hopes of extracting the perceived poison.

Mompesson’s Well sits on a lonely stretch of road high above Eyam. During the epidemic, to prevent cross-infection of neighbouring communities, food and other supplies were left at designated places on the outlying moors. The Earl of Devonshire, who lived nearby at Chatsworth House, freely donated food and medical supplies, but Eyam villagers paid for all other goods. The money was either purified by the running water in the well or was left soaked in vinegar at the boundaries of the village.

Joan Plant is descended from Margaret Blackwell, one of the plague’s survivors, and carries the CCR5-delta 32 genetic mutation. It is ten times more common than normal in the population of Eyam and has been studied as a possible route to a cure for HIV and Ebola.

In the church of St Lawrence is an oak cupboard traditionally believed to have been made from the box that brought the infested bundle of cloth to Eyam in the late summer of 1665. Now considered to be 18th century in origin, the cupboard is interesting in that it is adorned with indistinct markings that are thought to be ritual protection marks. These ‘hexafoil’ motifs, comprising overlapping circles, were once believed to ward against evil.

After the plague returned with a vengeance in the hot summer of 1666, even burials in the local churchyard were stopped and families forced to bury their loved ones themselves on their own land. Humphrey Merrill's solitary grave is located in a field behind his house.

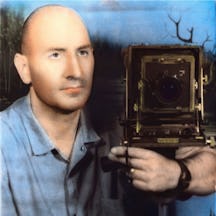

About the photographer

Simon Norfolk

Simon Norfolk is a photographer who regularly contributes to National Geographic and has shown his work at Tate Modern. He specialises in post-conflict landscapes; in particular he has worked a great deal in Afghanistan. His most recent book was following in the steps of the 19th-century photographer of the Second Afghan War, John Burke. Simon is currently running at a pretty nifty Number 44 on ‘The 55 Best Photographers of all Time. In the History of the World. Ever. Definitely’.