The Italians called it ‘the French disease’ and the French called it ‘the Neapolitan disease’. The Russians knew it as ‘the Polish disease’ and the Poles called it the ‘German disease’. To the people of Flanders and North Africa it was ‘the Spanish disease’, while to the Spanish it was known as ‘las bubas’. The British called it ‘the pox’, but you will know it as syphilis. Today a diagnosis of syphilis will require little more than a course of antibiotics and a few awkward phone calls, but it wasn’t always the case. As strains of sexually transmitted diseases are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics, it’s worth remembering the centuries of misery that syphilis unleashed and the desperate remedies our ancestors clung to before reliable treatment was available.

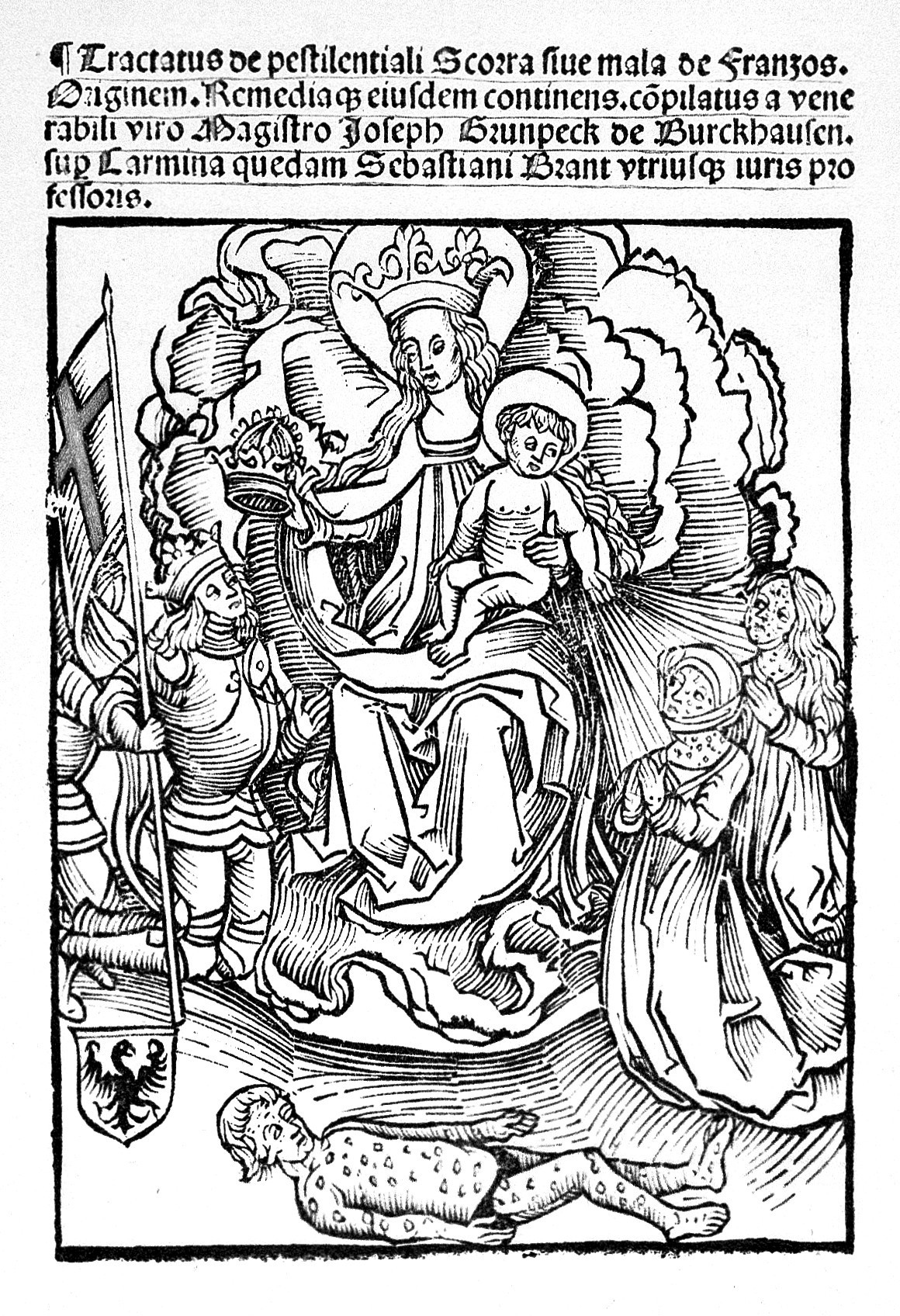

The origins of syphilis are intensely disputed by historians, who argue about whether or not syphilis was first picked up in the Americas by Columbus’s fleet in 1493, or if it has been around much longer than that. But, wherever it came from, by 1494 French troops besieging Naples had come down with a very nasty disease indeed. This work by Sebastian Brandt dates to 1496 and shows the baby Jesus throwing spears of light to punish or cure the sufferers of syphilis, who are shown covered in ulcers and sores.

The term ‘syphilis’ was first introduced by the Italian poet Girolamo Fracastoro in his work ‘Syphilis sive morbus gallicus’ in 1530. Fracastoro writes about a shepherd called Syphilus who is cursed with a terrible disease by the God Apollo, but is later cured with mercury and tree resin. This 16th-century engraving by Jan Sadeler shows Girolamo Fracastoro warning Syphilis not to anger Apollo by pointing to Venus, the Goddess of Love. ‘A night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury’ ran the old adage.

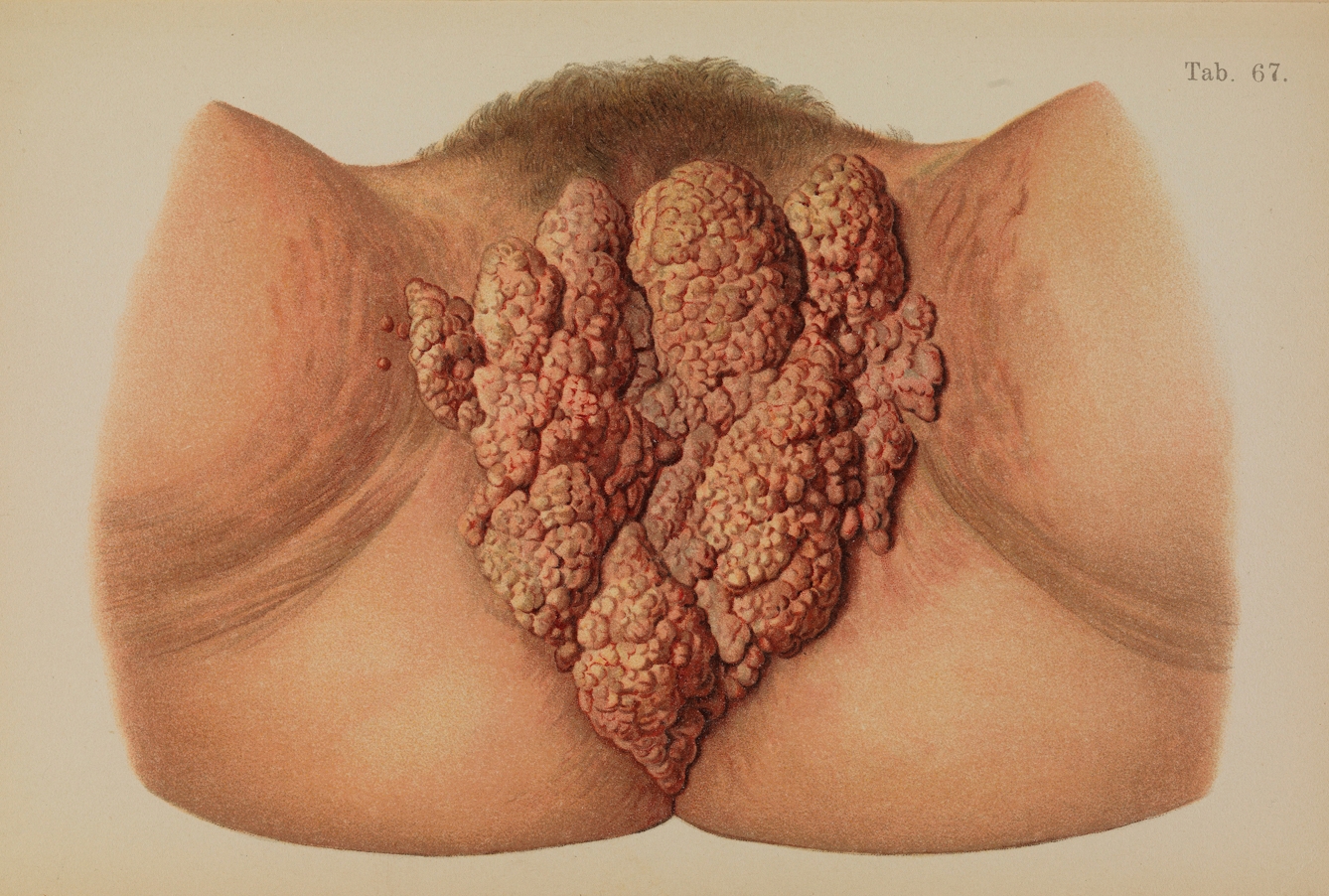

When German physician Joseph Grunpeck (1473–1532) became infected with the disease, he described syphilis as being “so cruel, so distressing, so appalling that until now nothing more terrible or disgusting has ever been known on this earth”. In its early, primary stages, syphilis causes weeping sores called chancres to appear on the genitals. The disfiguring lesions were carefully documented by Dr Franz Mraček (1848–1908) in his ‘Atlas and Epitome of Diseases of the Skin’.

Within a few weeks of the chancre healing, the secondary stages of syphilis bring a rash that covers the body, flu-like symptoms, and wart-like sores in the mouth or on the genitals. The sufferer is at their most contagious during this stage, and although symptoms usually disappear within a few weeks, they may linger for up to a year. After this, the disease moves into its latent stage, where the sufferer exhibits no outward symptoms. However, it is at this stage that the disease begins slowly attacking the heart, brain, nerves and bones.

After years of appearing to be symptom-free, the sufferer will enter the tertiary stage of syphilis. Deep ulcerations appear on the face, eating away at the bone and causing the ‘saddle nose’ typical of the pox. Lesions disfigure the bones, tumour-like growths appear all over the body, and once syphilis is in the nervous system, seizures, dementia and blindness soon follow.

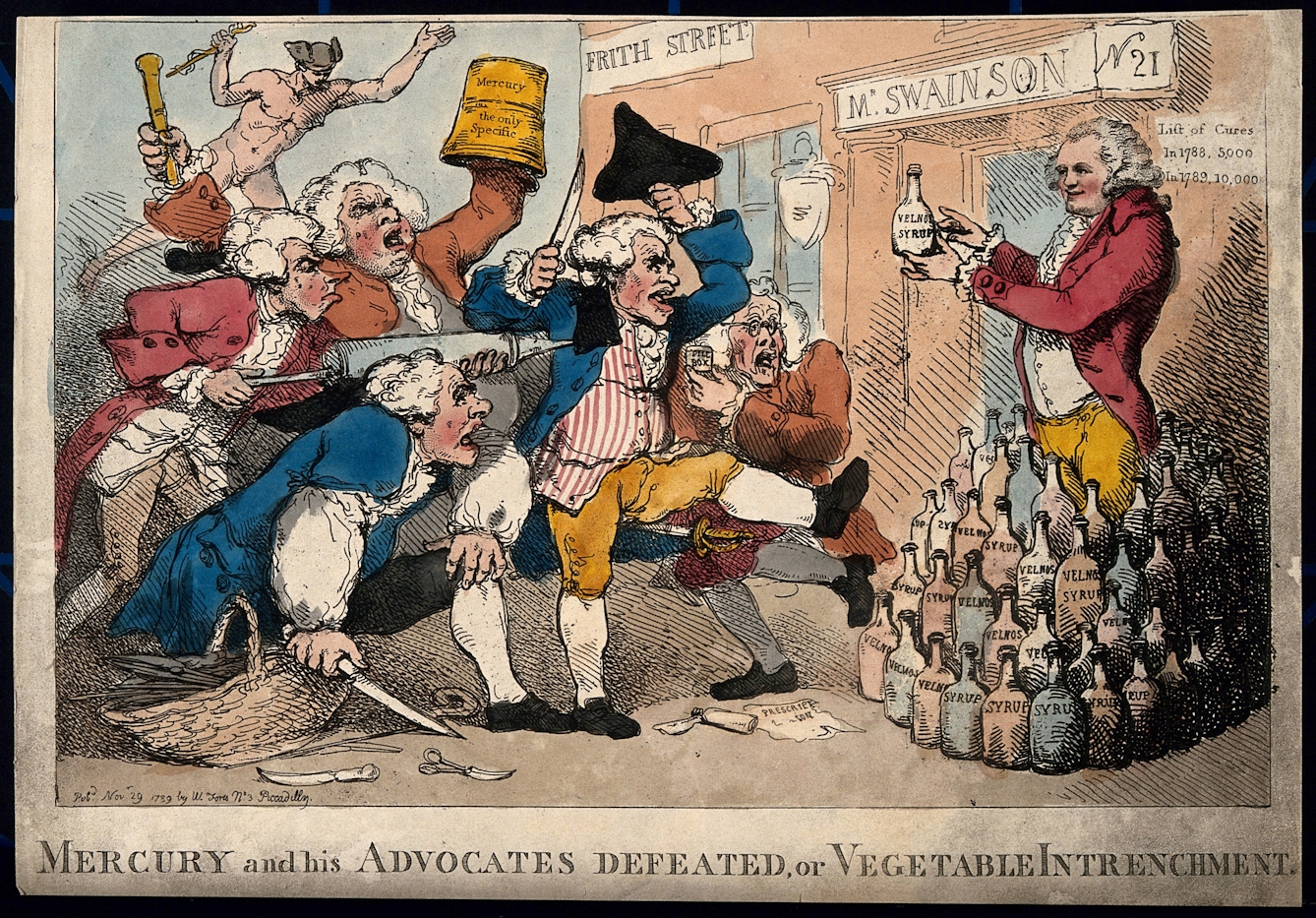

Mercury was a common, if expensive, treatment for syphilis. It could be ingested, rubbed into the sores, or injected directly into the urethra, as this 19th-century French mercury douche demonstrates. Mercury may have been effective in burning away syphilitic lesions, but it is also highly toxic and causes all manner of neurological problems, as well as swollen gums, rotting teeth and hair loss.

In 1776 Parisian physician Chevalier Lalonette pioneered ‘mercurial fumigation’, which saw the patient sitting in a closed box while a ‘mercurial preparation’ was heated below them. When physician John Pearson (1758–1826) tried Lalonette’s contraption he found that the patient’s gums quickly became “turgid and tender”.

Others, such as Isaac Swainson (1746–1812), believed the pox could be cured without the use of mercury. Swainson’s Velno’s Vegetable Syrup claimed to be able to cure syphilis, along with leprosy, gout, scrofula, dropsy, smallpox, cancer, scurvy and diarrhoea. Swainson made over £5,000 a year from its sales, and built his own botanical garden in Twickenham with the profits.

But neither mercury, fumigations nor quack syrups could do anything to halt the devastation of syphilis. Lock hospitals and sanatoriums, like Dr Abreu’s ‘sanatorium for syphilitics’ in Barcelona, were overwhelmed with demand, but could do little to help.

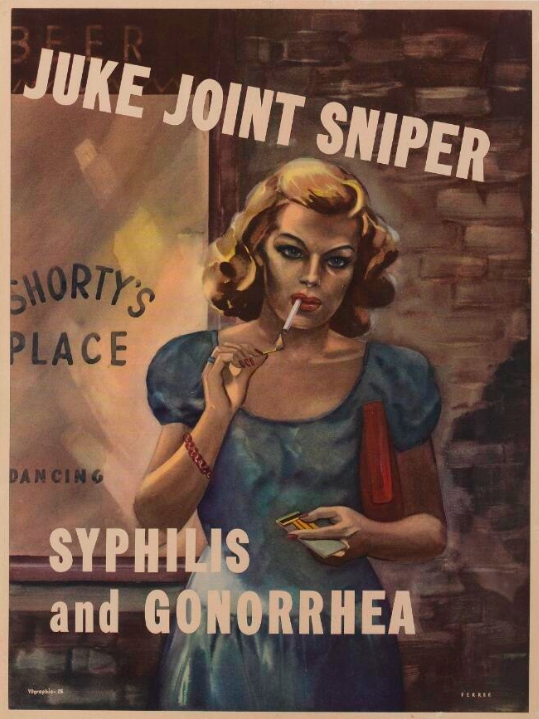

Public-health campaigners of the 19th century feared syphilis would bring down the armed forces, and blamed the spread of the disease on women who sold sex. The British government passed the Contagious Diseases Act in 1864, which allowed women suspected of being a ‘common prostitute’ to be forcibly detained and examined for venereal disease. The act was finally repealed in 1886, but the association between ‘loose women’ and VD continued.

During World War II, the American government bombarded its troops with warnings to stay away from ‘immoral women’ and the diseases they carried.

After hundreds of years of suffering, the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s meant that infections such as syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia could finally be cured. But today, with less than half of young people regularly practising safe sex, syphilis is on the rise once more. In 2017 there were 7,137 cases reported in England, a 20 per cent increase from 2016, and a shocking 148 per cent increase from 2008. Before you decide to risk it, spare a thought for our ancestors and the horrors of syphilis they had to endure – and always wrap it up.

About the author

Dr Kate Lister

Kate is a sex historian and author of several books, including 'A Curious History of Sex'. She is the host of the hit podcast 'Betwixt the Sheets', a weekly columnist for iNews and occasional TV presenter.