For over 500 years, scientific and artistic collaborations have enhanced and promoted medical knowledge. But 18th-century output, sandwiched between early monochrome drawings and today’s digital images, came from particularly striking partnerships.

From the early modern period, as perceptions of the internal and external workings of the body developed, the methods of depicting the body also advanced. But it was not until the 1750s that anatomical art truly began to flourish. The number of medical schools in Europe was growing, but with an extremely limited supply of corpses available for dissection, visual stimulus was essential. This offered a golden opportunity to broaden artistic horizons.

A colourful ambition

Until the mid-18th century, illustrated medical texts were largely monochrome with occasional hand-colouring. In 1722, Elisha Kirkall was one of the engravers who trialled the use of mezzotint to print illustrated lectures in colour. He used a tool called a rocker to roughen up copper or steel plates to create texture for printing.

But most notable of the artists to experiment with intricate colour techniques was the “swaggering but talented mountebank”, Jacques Fabien Gautier d’Agoty. This ambitious French anatomist, painter and printmaker had added the ‘d’Agoty’ to his name to sound more fancy, and was notorious for claiming to be the true inventor of the trichromatic mezzotint printing method, which used blue-yellow-red layers to create vivid colour images.

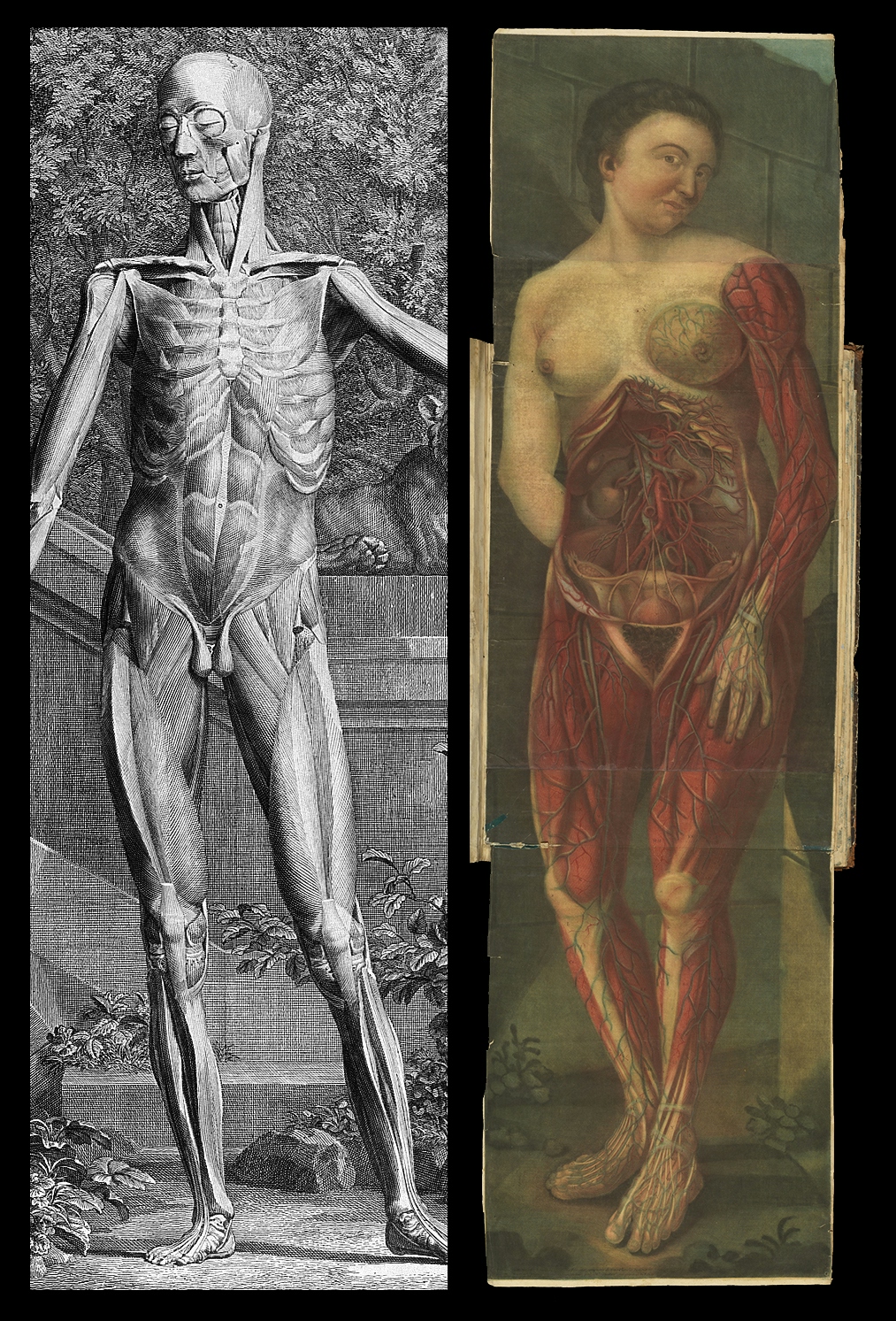

The image on the left is from an Albinus book, and the one on the right is an engraving by Gautier. Both are from the 1740s, but there are significant differences both stylistically and in terms of techniques used.

This bold boast dented Gautier’s reputation at the time because it was known by others in his trade to be a lie: Jacob Christoph Le Blon actually first developed the technique and taught it to Gautier, who waited until Le Blon died before trying to claim it as his own ingenious idea. Gautier’s real genius lay in finding the right audience to market the technique.

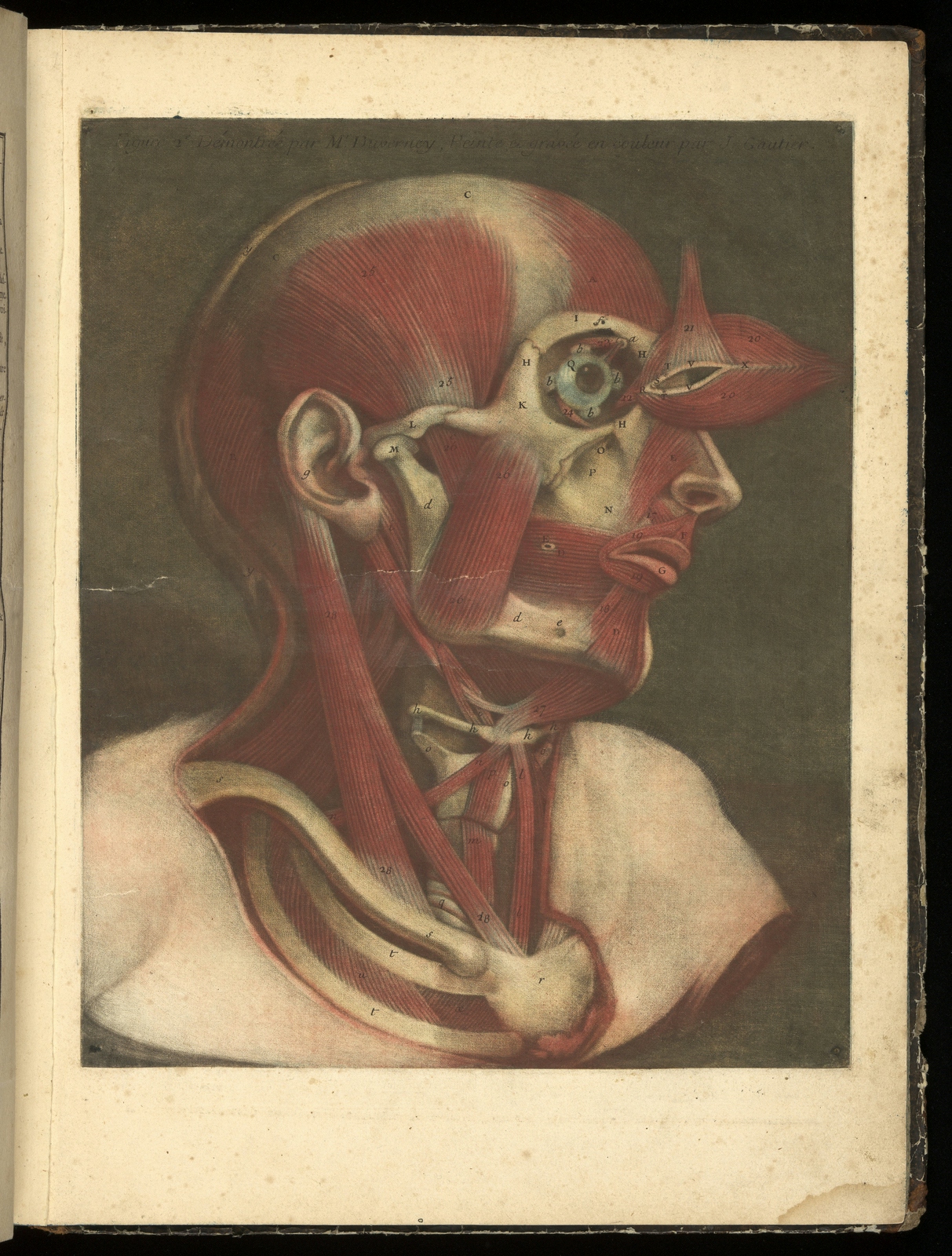

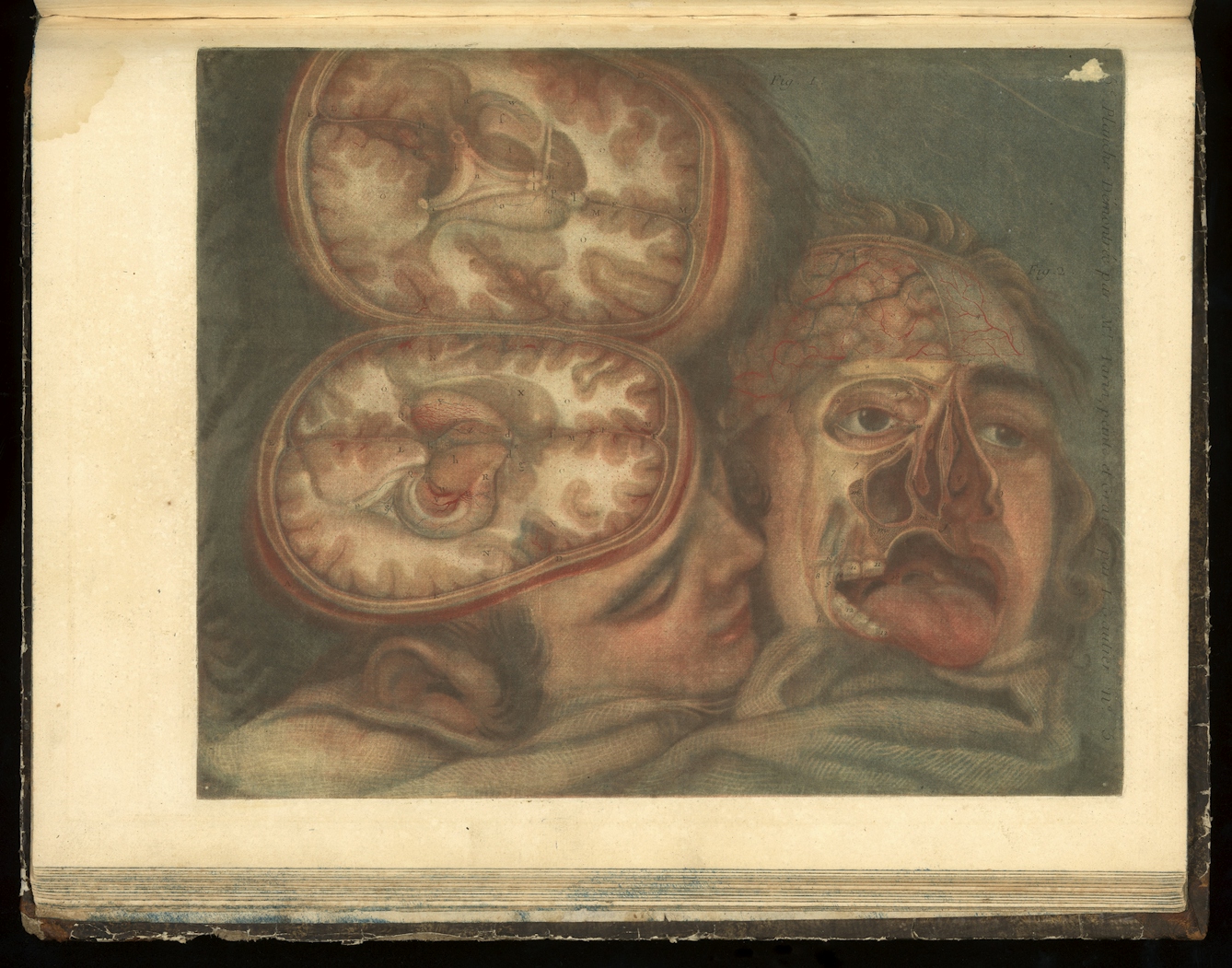

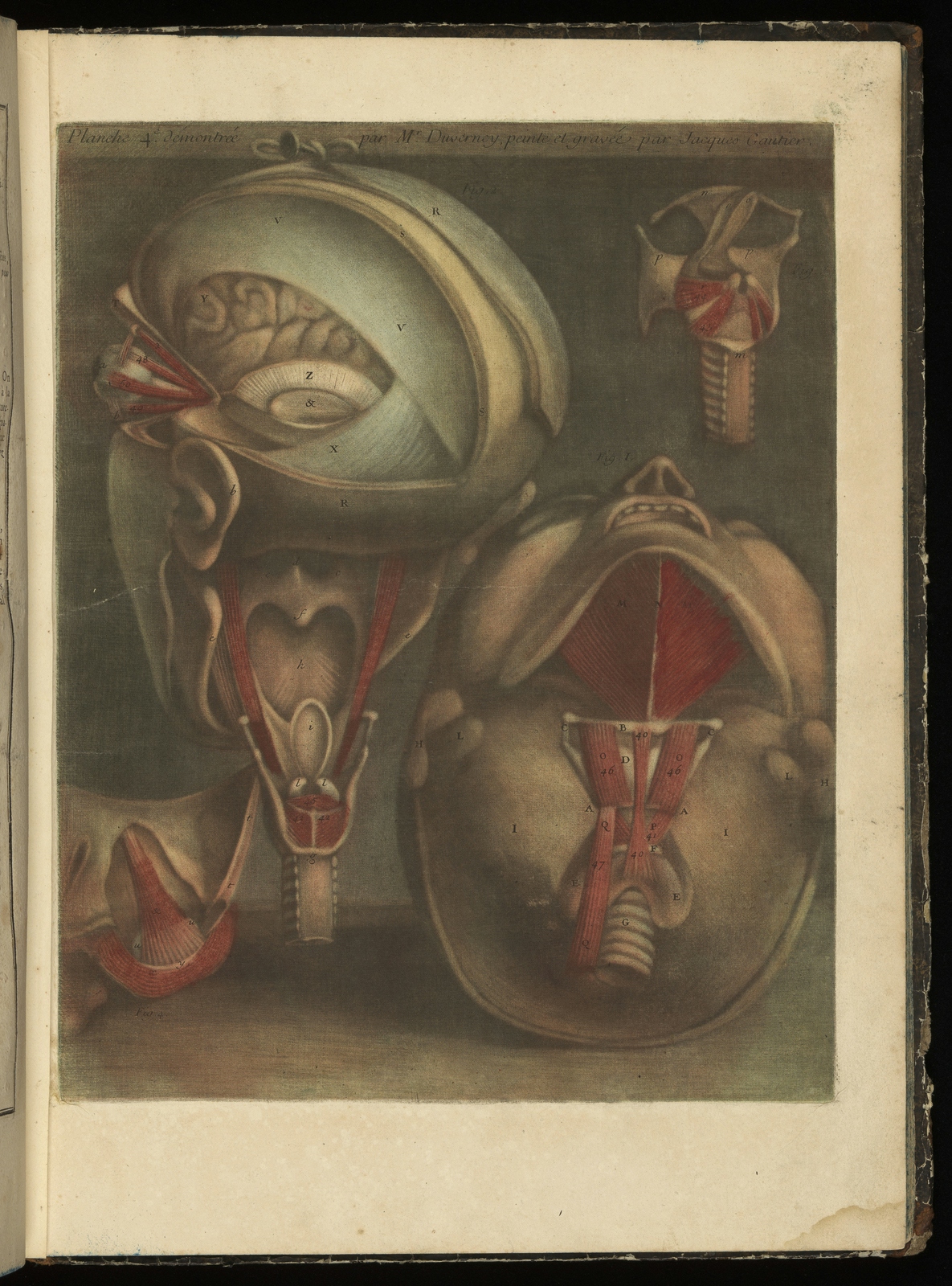

In 1745, Gautier aimed to make his prints the recommended texts for all students of medicine. He collaborated with Guichard Joseph Duverney, a lecturer in anatomy in Paris, and over the next few years they published three large anatomical texts with sumptuous illustrations using a complex and painstaking multiple-plate mezzotint method.

A powerful publishing partnership

Three or four layers would be printed on the same sheet to achieve the different colours of this single image.

Gautier often represented his figures in sensual poses rather than classical stances.

Gautier based his prints on first-hand study of dissections, and a contemporary advertisement for these medical illustrations promoted them as an "absolute necessity for surgeons, painters, sculptors, and, in a word, for all those dedicated to the study of the human body".

However, even much more recently his style has been questioned, with one critic suggesting in 1992 that his illustrations were “probably aimed at more prurient-minded lay persons than at anatomists”.

Clinical yet seductive

Gautier was no scientist, more an artist virtuoso, whose “science was more remarkable for its quirkiness” and reaction to his expensive publications was mixed. Not only did Gautier print colour in a three-dimensional, tonal way – only achieved through the repeated grinding of the mezzotint ‘rocker’ – but he used female models.

Compared to conventional male studies, Gautier’s figures must have ruffled medical feathers. His models were posed and almost seductive: he angled them to best display their inner workings, using the tonal differences of colour to enhance and enliven their softly lit bodies.

Duverney clearly liked Gautier’s new approach, claiming in one of the books they collaborated on, ‘Myologie’, that: “Colour printing can nowhere make a greater contribution to scientific understanding than in anatomy.”

And Gautier’s publishing dynasty was testament to the success of his methods. His five sons continued their father’s publishing business in different guises until the 1770s, and the family workshop dominated the French medical publishing market.

Gautier’s figures must have ruffled medical feathers. His models were posed and almost seductive.

A demand for precision

In time, the intricacies of layering colours via mezzotint proved too expensive for medical publications and unsuitable for the increasingly technical methods used in surgery. New medical approaches required new art.

By the early 19th century, the focus of anatomy had moved to the study of systems of membranes and tissues, and the recording of surgical feats. Pathological analysis became more detailed and the preparation of specimens became more precise.

Artistic expertise was crucial to medical dissertations on new methods of repairing or simply studying the body, and a more meticulous form of illustration was required.

So it is not surprising that renowned artists like Charles Turner moved into medical illustration. Turner was a mezzotint engraver by royal appointment and known more for his traditional portraits than his medical illustrations.

He collaborated with surgeon J B Carpue, in his ‘Account of Two Successful Operations for Restoring a Lost Nose from the Integument of the Forehead’, 1816, about a new surgical technique. For this essay, Turner tried his hand at the à la poupée method of printing to better depict the delicate tissue. This involved dabbing different coloured inks onto the metal plate using a wad of fabric to blend and create very detailed and accurate representations of colour and tone.

The image on the left is a 16th-century depiction of rhinoplasty, and on the right Turner's collaboration with Carpue from the 19th century. The styles of both surgery and engraving have changed significantly.

King George IV appreciated both Turner and Carpue, and they likely mixed within the same social circles. Commissioning the accomplished artist to illustrate his book undoubtedly helped the surgeon to promote his own work. Though the readership of such books was limited, they could be influential: Carpue’s essay revived a 16th-century technique for rhinoplasty.

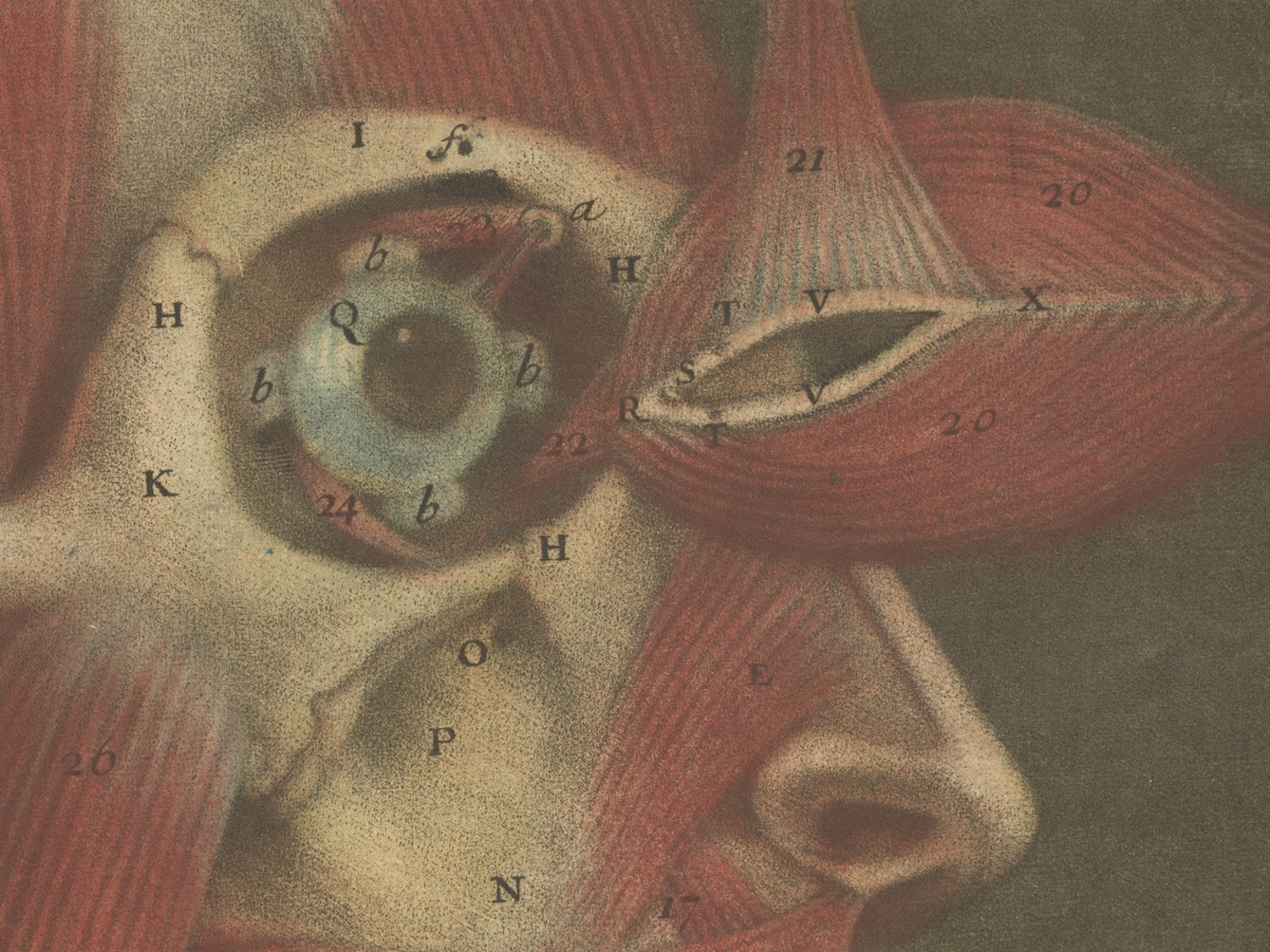

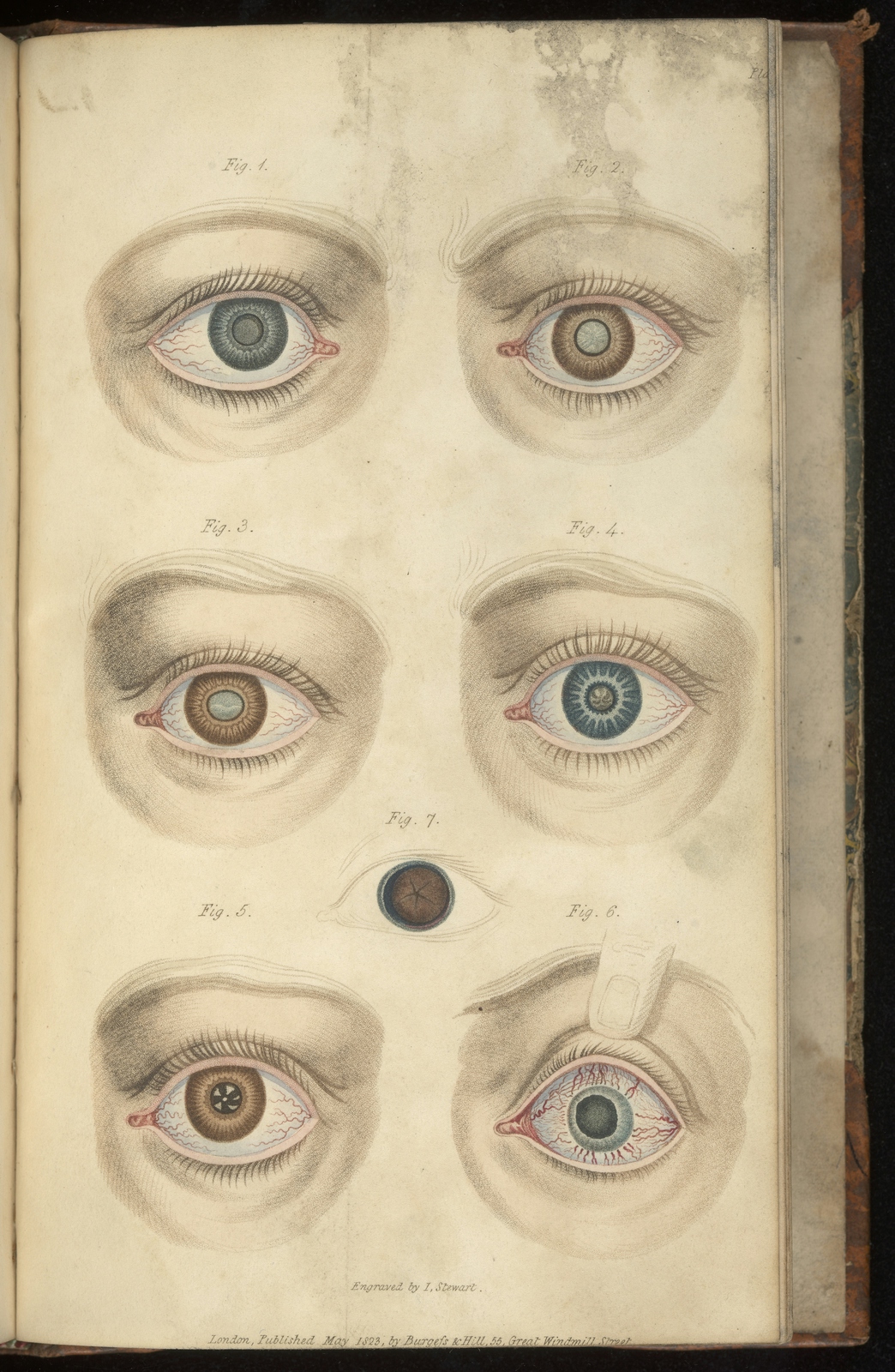

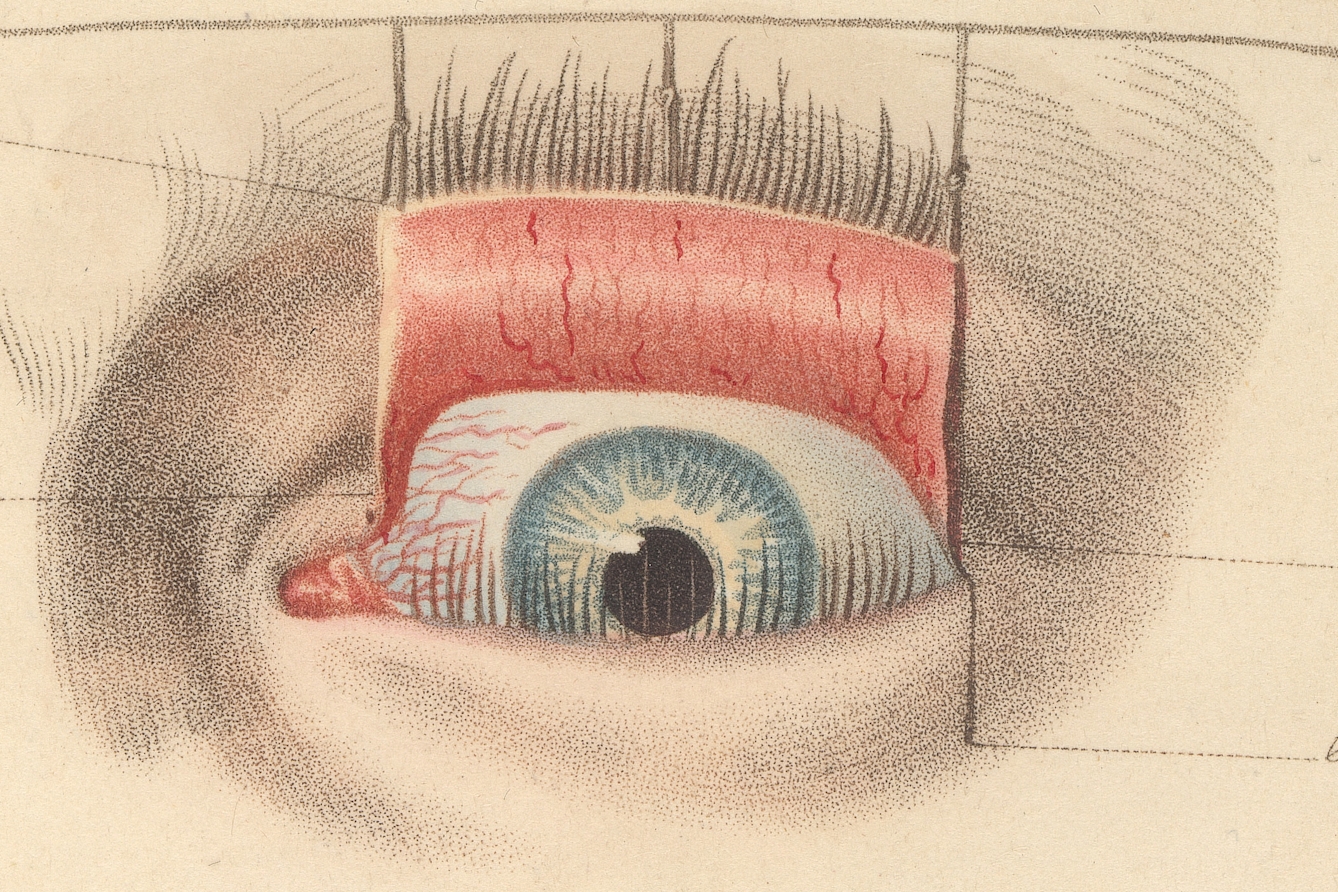

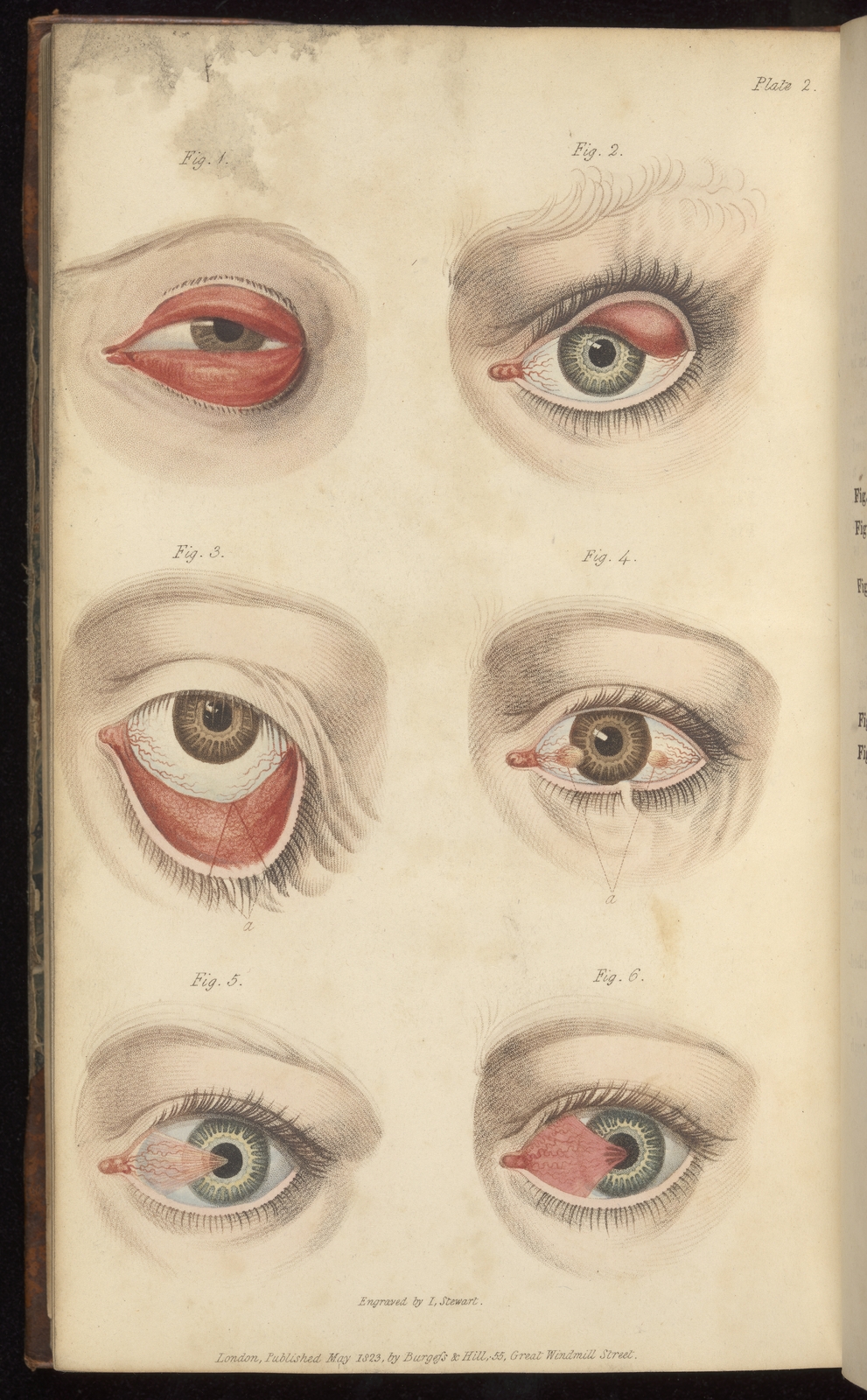

Lesser-known artists also collaborated with medical publishers, particularly in the early 19th century. The name ‘J Stewart’ regularly appears on medical illustrations in the 1820s. Stewart’s illustrations, also coloured using the à la poupée technique, enhanced published lectures such as G J Guthrie’s ‘Lectures on the Operative Surgery of the Eye’ from 1827. Guthrie, assistant surgeon and lecturer at Westminster Hospital, performed innovative eye surgery, and would probably have known about Stewart’s previous work for the anatomist and illustrator John Bell.

An eye for colour

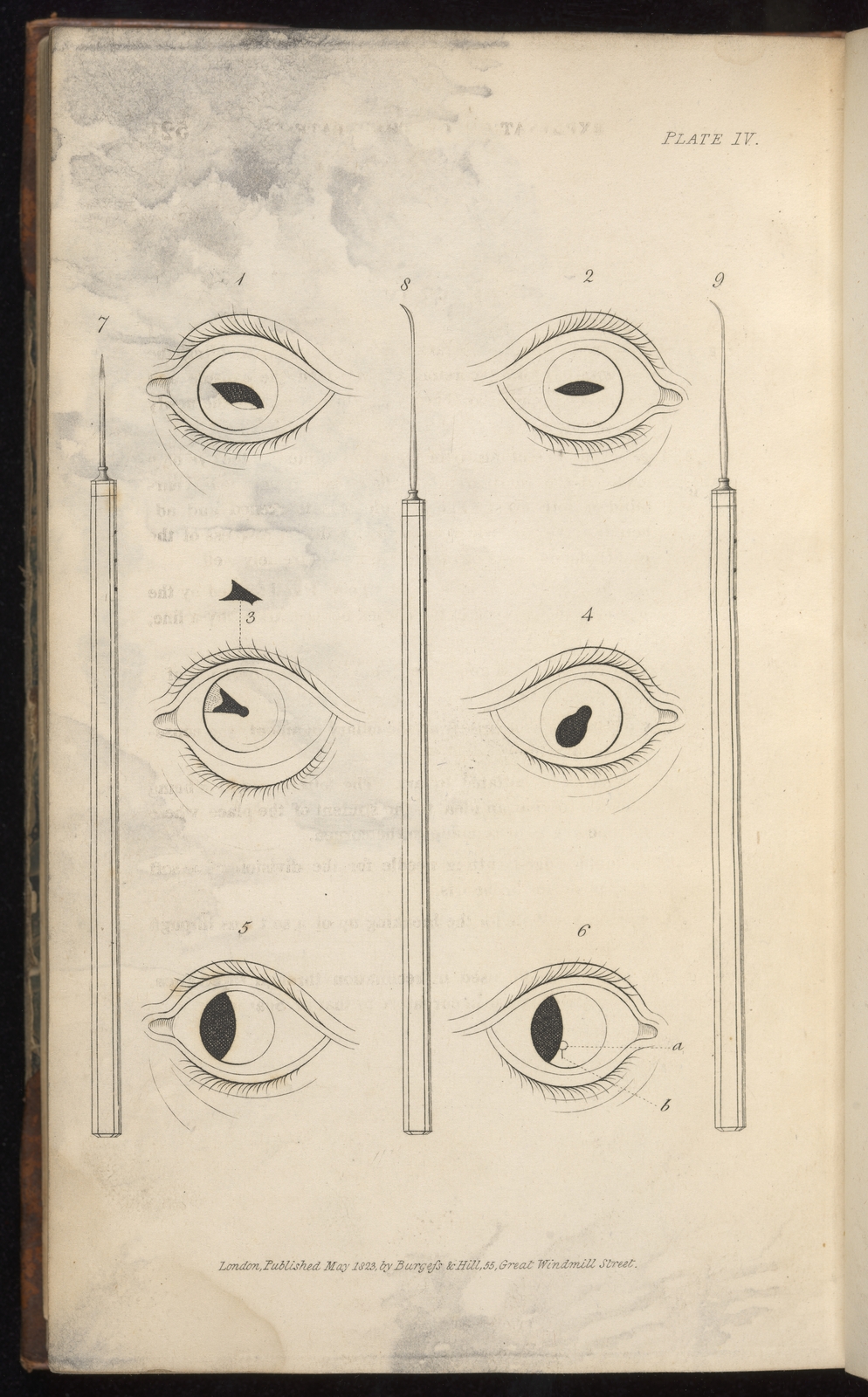

This page represents different types of cataract, which were one of Guthrie’s specialities. He advocated for removing cataracts by surgical methods.

This close-up illustrates how Stewart used the à la poupée method of creating lots of tiny dots to depict details.

The 1845 ‘British and Foreign Medical Review’ published a scathing critique of a book by Guthrie’s son Charles Gardiner Guthrie, which it felt was too similar to his father’s work, even down to the illustrations: "We were stared into a state of almost mesmeric fascination by the same nine horrid eyes, each in the same identical spot… all goggling at us with the same genuine ophthalmological ghastliness!"

This is a far more simple illustration printed in black and white. The focus is on the artificial pupils created by different sorts of surgical incision.

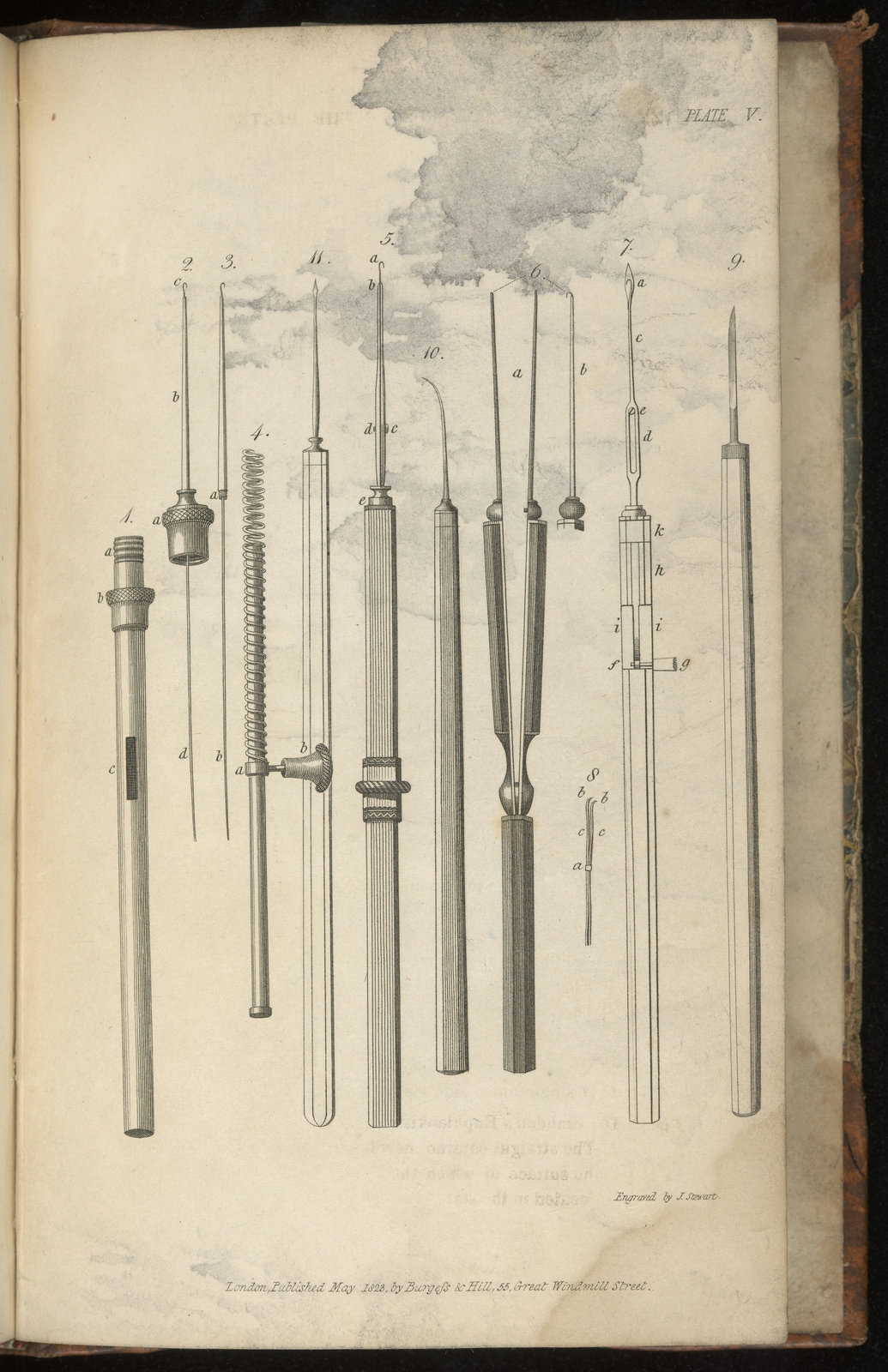

This black-and-white illustration has more detail than that of the incisions, and is used to illustrate the different medical implements that might be used by an ophthalmic surgeon like Guthrie.

Just as in Gautier’s time, finding the right audience for these vivid anatomical works was key to ensuring the time and effort taken to produce them was worthwhile. Some publishers, such as Burgess and Hill, based in London, used subscription fees to fund production costs and ensure there was a readership. Subscribers could view books in a dedicated ‘medical reading room and library’, a more practical ‘book club’ solution that would have benefited Gautier’s pricey publications some fifty years earlier.

A more modern technique

As techniques in printing and pathology altered during the 18th and early 19th centuries, so too did the relationship between artist and surgeon. Eventually, towards the mid-19th century, lithography (which used chemicals rather than scratching with a rocker to engrave a plate) replaced the older and more complex colour-printing processes, because it provided a cheaper alternative.

Lithograph printing was initially done by hand, such as in the case of Robert Carswell’s Pathological Anatomy, 1838, but it later became possible to create multiple printed impressions, as used to illustrate Joseph Maclise Surgical Anatomy, 1856: this was obviously much speedier and less expensive.

Until the advent of digital printing, lithography remained the dominant colouring process in medical illustration. Though today’s digital techniques are unlikely to depict sensual models with flayed bodies, the highest respect is still reserved for artists who, like Gautier and Turner, demonstrate ‘exceptional use of technique, understanding and interpretation of the subject’.

About the contributors

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. She currently runs the Exploring Research programme, and has a particular interest in the medieval and early modern periods, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.