The innovative designs for two 1930s health centres grew from separate principles, both serving city communities. Behind one was the Peckham Experiment, based on health promotion, while the other actively fought disease.

Two health centres, two ideologies

Words by Emily Sargentaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

On a quiet residential street in south-east London stands a building once described by Walter Gropius, Bauhaus founder and architect, as “an oasis of glass in a desert of brick”.

It’s a building I’ve walked past many times, now partially obscured by the large gates that describe its current function as sought-after private flats. Peering across the car park and tennis court, you can see the scalloped glass windows that allow the interior to be flooded with light, and the clean lines of the whitewashed exterior.

Surrounded by solid brick Victorian structures, as well as some more recent interventions, the sense of this building as a breath of fresh air – an oasis – remains.

The former Pioneer Health Centre is “an oasis of glass in a desert of brick”.

But this building wasn’t designed as housing. The Pioneer Health Centre, as the building was originally known, was home to the Peckham Experiment, founded in 1926 by social biologists George Scott Williamson and Innes Hope Pearse.

Health through self-care

This inquiry into the nature of health was intended to inspire a revolution in self-care and community – providing people with the opportunity and facilities to take a vested interest in their own health.

The Pioneer building opened in 1935 and used the healthy principles of light, ventilation and openness in its design. Furniture, designed by Christopher Nicholson, was lightweight and easy to move around to encourage flexible use of the open-plan spaces. Cork floors were used to encourage people to go barefoot.

More: How the Peckham experiment inspired my fiction

The building was designed to provide a healthy environment in which the biologists could monitor the activity of the members: a space for “observation without interference”, as the Head of the Architectural Association, Robert Furneaux Jordan, wrote in 1949.

A box of early photographs kept in Wellcome Collection’s archive of the Peckham Experiment gives me some insight into activities at the centre. This one shows families enjoying the swimming pool, while others show children roller-skating, taking in sunshine on the roof and tending flowers in the garden.

The centre operated as a family club in which adults and children could access “any or all of the activities to support their health and happiness”, according to an introductory pamphlet produced for local residents. They also reveal the underlying scientific enquiry – the yearly medical examinations; an image of an infant lying on a light box being closely studied – the ever-present element of observation, which the building’s open architecture supported.

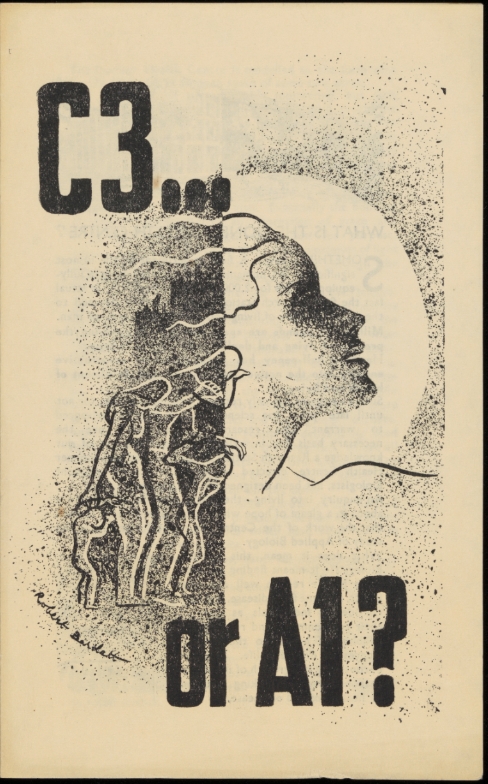

The cover of the leaflet bears a mysterious message: “C3 or A1?” Pearse and Williamson’s book ‘The Case for Action’ provided the clues I need to understand both this cryptic question and the underlying motivation for the experiment. Conscription for World War I had identified many individuals living neither in health nor in sickness: “There was a third condition: C-ness. They were not sick, nor were they healthy. They were ‘invalid’ for work or fighting – devitalised.”

The British Army Medical Categories in 1914 declared that category A was “able to march, see to shoot, hear well and stand active service conditions”, with subcategory A1 “fit for dispatching overseas, as regards physical and mental health, and training”. The C category was “free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service in garrisons at home”, while subcategory C3 was “only suitable for sedentary work”.

Positive eugenics and politics

The experiment focused on encouraging health, rather than fighting disease, as well as empowering the people to actively participate in the pursuit and preservation of their health – all under the watchful eye of Pearse and Williamson.

Later in the book I came across this statement: “While concentrating on disease in the unfit, we have been ignoring the development of health in the fit. We have been blindly and diligently working to reverse the law of Nature by procuring the survival of the unfit.” It makes unsettling reading – and demonstrates why the centre has attracted accusations of exercising ‘positive eugenics’.

The experiment focused on encouraging health, rather than fighting disease.

Politics was never far away from the Peckham Experiment, and the foundation of the NHS in 1948 saw its closure. Despite widespread support for the model that the centre espoused, it was seen as largely incompatible with the structure of the NHS. The centre closed its doors in 1950, but the Pioneer Health Foundation remains active.

In late 2018 I heard the phrase ‘self-care’ again, on the radio news. Matt Hancock, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, was launching a new vision for health based around prevention. Perhaps these ideas, now nearly 100 years old, are once again part of our future.

The Finsbury Health Centre

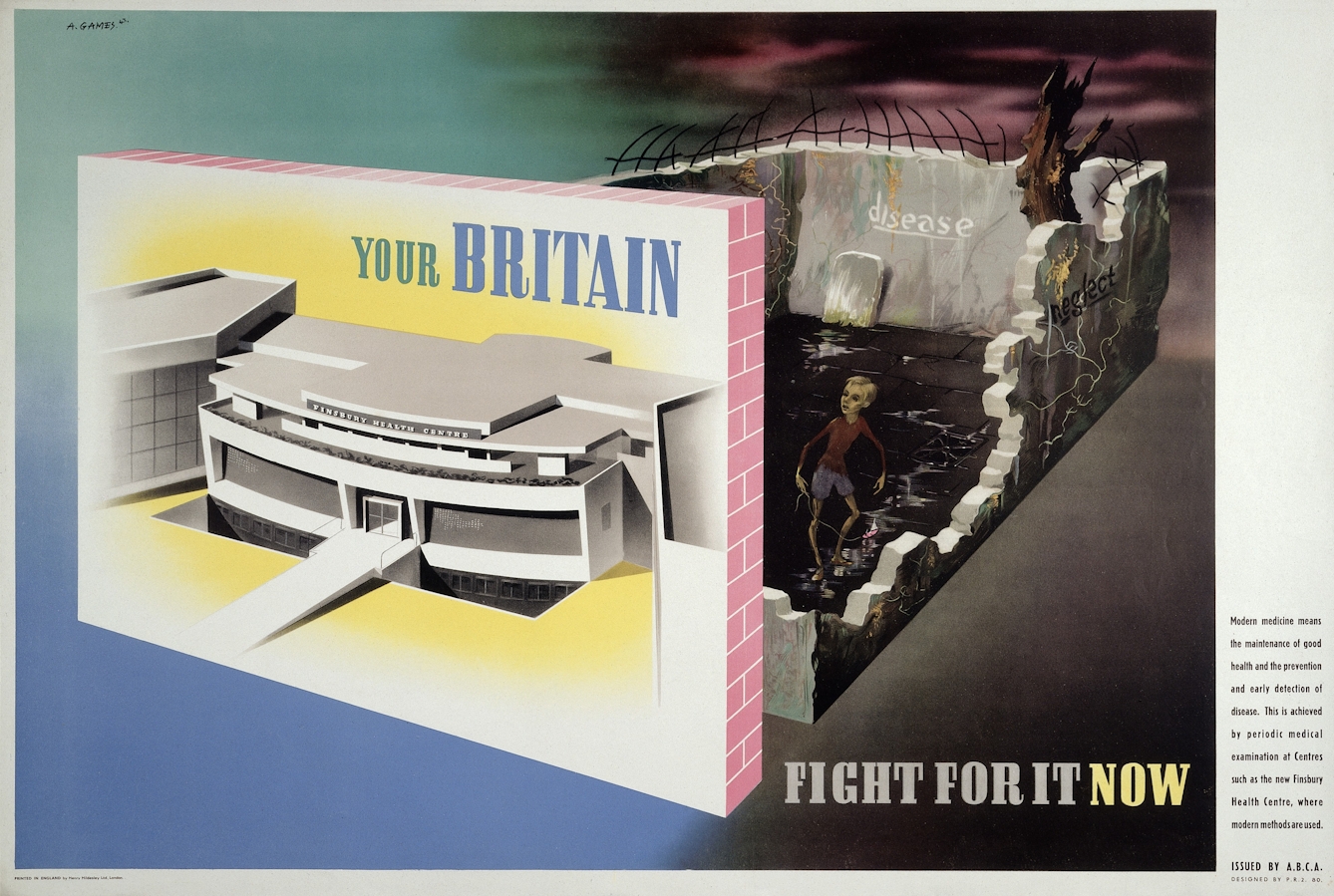

While Peckham was “organised for health”, another mid-century London health-centre building marked a frontline response to fight disease. The central district of Finsbury, a metropolitan borough from 1900–65 and now part of Islington, became home to the Finsbury Health Centre in 1938, designed by Berthold Lubetkin of the Tecton architectural group. My first encounter with this iconic building was on a poster by seminal 20th-century graphic designer Abram Games in Wellcome Collection’s library.

This poster’s striking design shows the distinctive Finsbury Health Centre – shaped to operate as a “megaphone for health” – contrasted with a dilapidated brick structure. The word ‘disease’ is scrawled on the wall and a bow-legged child bears the results of rickets – a disorder associated with lack of sunlight and poor diet.

The poster, published by the Army Bureau of Current Affairs during World War II, makes the case for modern architecture, but its representation of slum conditions horrified Winston Churchill, who suppressed the publication of this poster and two others like it.

Churchill considered the imagery to be “a disgraceful libel on the conditions prevailing in Great Britain before the war”. Games later responded that “Churchill may have been a great wartime leader, but he’d never visited a slum”.

Fresh air for fighting disease

The range of services available at the Finsbury Health Centre reveal the needs of the community and reflect the prevalent experience of urban living at this time. The centre’s primary function was as a tuberculosis centre – a widespread public health problem.

Clinics on the ground floor offered services including dentistry, podiatry and maternity, as well as sun-lamp therapy – a photograph shows rows of children in their sun goggles receiving treatment. A futuristic machine was housed in the basement for the disinfection of bedding and clothing, together with a ‘confiscation room’ for meat considered unfit for consumption.

A mural in the lobby, painted by Gordon Cullen, recommended “Fresh Air Night and Day” to those waiting in the foyer space, lit by the glass bricks that formed the front wall of the centre. Cullen also made a series of cartoons explaining the design of the building in positive terms (‘Very Easy Ramp’; ‘Convenient Circulation’; ‘Clean Modern Lines’) and comparing it with existing medical buildings (‘Too Many Stairs’; ‘Stagnant Air’; ‘Pompous’; ‘Pretentious!’).

A futuristic machine was housed in the basement for the disinfection of bedding and clothing.

These panels, each describing a particular aspect of the design, were put on public display in an exhibition entitled ‘Getting it Across to the Layman’. Despite the somewhat patronising title, the drawings made a case for the building and were intended to engage the local community with its design.

Helen Cagnoni, a local resident and lifelong user of the Finsbury Health Centre, gave us her oral history and recalled her sense of pride in the building: “It just gives you a different feeling to being in an ordinary building where you’ve got a window here and a window there… it gives you that feeling that you’re in something that is visually extremely unusual and wonderful.”

The Finsbury Health Centre remains part of the NHS, providing healthcare to the local community. Dentistry and podiatry clinics remain, but others, like the sun-lamp treatment room, have been left behind.

Some of the building’s original features were lost during World War II, including the mural. Despite a partial restoration in the late 1990s, parts of the centre are now falling into disrepair. The original windows, innovative in their design, now wear the signs of age.

More than 80 years after its original construction, paint is peeling from the Finsbury Health Centre’s exterior walls, and the railings in front of the centre veer at a drunken angle.

The future of this iconic building seems uncertain, but it remains a visionary example of how architecture and modern design could be used to embody the elements of good health.

But could architecture itself go one step further and begin to heal, I wondered? To try and answer this question, I would need to fly to Finland.

About the author

Emily Sargent

Emily Sargent is Senior Curator at Wellcome Collection. She has curated numerous large exhibitions on a wide range of subjects, including 'Living with Buildings' (October 2018–March 2019), and exhibitions on human enhancement and the experience of consciousness.