Many architects’ plans intend to improve the quality of life for those using their buildings, and to nurture good mental and physical health. But designing and building these spaces can take a serious toll on the wellbeing of everyone involved.

While architecture is considered by many as a dream job, a 2016 Architects’ Journal student survey revealed that one in four architecture students in the UK has been treated for mental health issues. The rate increased to one in three when the survey was conducted again in 2018. In the US, a 2012 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used data from 17 states to determine that Americans in the architecture and engineering professions are the fifth most likely to commit suicide compared to other occupations.

Those who carry out the backbreaking work of bringing an architect’s vision to life were at an even higher risk of suicide, according to the CDC study. Construction workers were in second place compared to other lines of work, followed by those working in installation, maintenance and repair at number three.

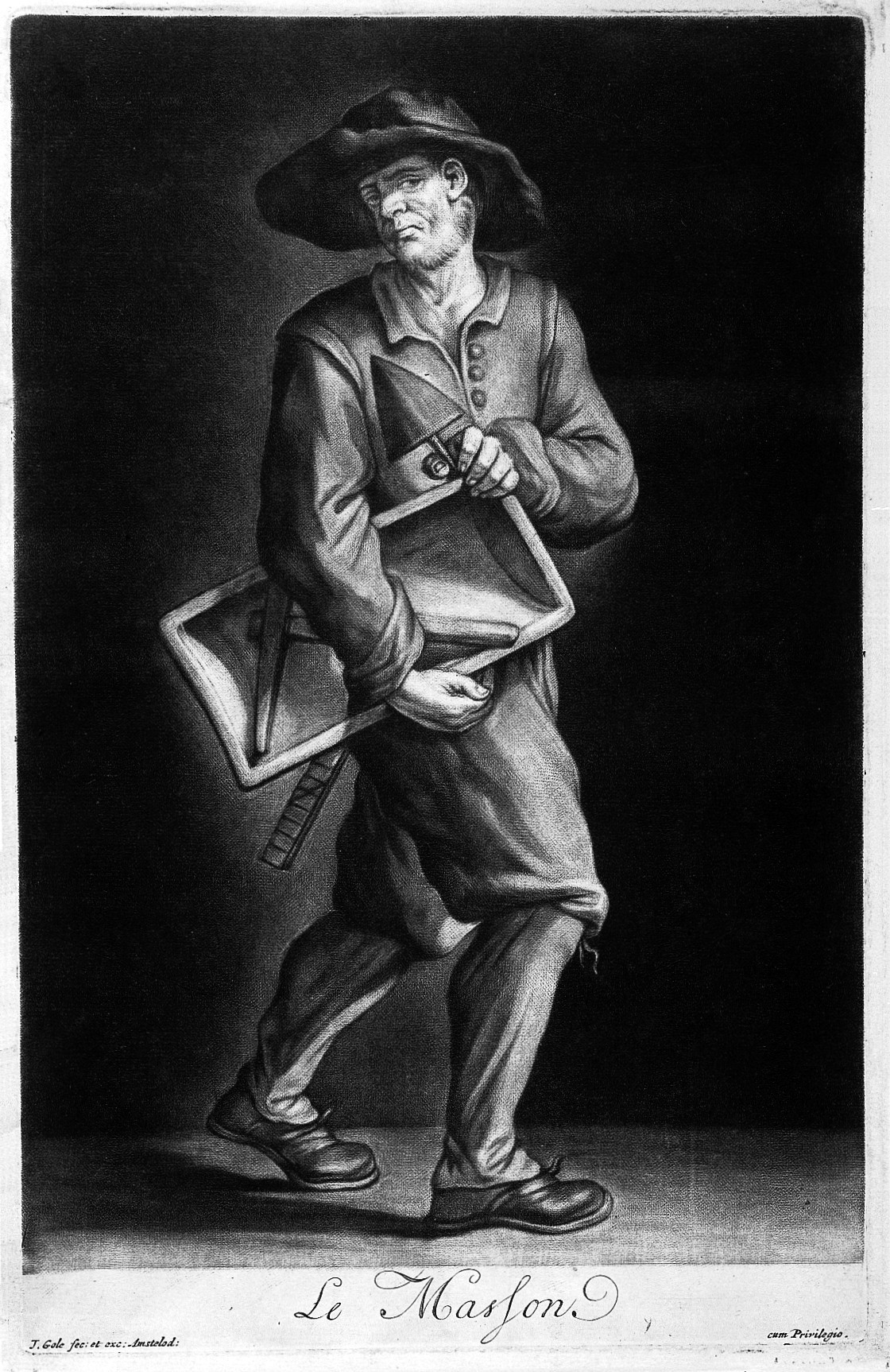

Construction work can be dangerous: here, a Saint is trying to intercede and save a falling labourer. But there are mental health risks that builders may need better protection from as well as physical ones.

And according to an article by Talha Burki in the Lancet Psychiatry journal, from 2011 to 2015 1,419 people working in skilled construction and building trades in England took their own lives. The rates of suicide among low-skilled construction workers were three to seven times higher than the natural average during the same period.

The number-one worry for nearly half of 469 UK-based student respondents of the 2018 Architects’ Journal survey was the cost of completing an architecture education, which can exceed £100,000. But even those lucky enough to fund and complete seven years of architecture school go on to face mental health challenges in the workplace.

MORE: The female fight to reclaim our space in the mosque

“There are certain characteristics about the way architects work which can add to the likelihood that mental health issues will occur,” Virginia Newman, director of KSR Architects and board member of UK’s Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), writes. She cites factors such as poor pay, long hours, feast-or-famine workloads, the unrelenting need to defend their design choices and the lack of union or HR support for the majority of architects who work for smaller practices. Newman writes that practical steps to address these issues include training designated staff to detect warning signs and offering employees mental health cover.

A not-so-modern problem

While it’s tempting to blame the current mental health crisis on modern stressors, the London-based Architects Benevolent Society was founded in 1850 to support struggling professionals including destitute and disabled architects.

This image of a sad-looking architect attests to the age-old pressures faced in this career, such as working on frustrating projects. Its original caption translates roughly to say: “I am a modern architect, and this hand disdains to work on old things. But I tried to attest this in vain: they speak only of my work on the walls.”

ABS observes that “surprisingly, these early cases are typical of the difficulties which still affect many people in the architectural profession today,” and it includes a number of testimonials from beneficiaries on its website.

“While some architects achieve great distinction in their profession and can achieve considerable financial success, there are a significant number who suffer hardships of many kinds. It is a disturbing fact that (on average) one in 20 members of the wider architectural profession will need to seek help from us at some stage in their lives.”

Today, the ABS spends in excess of £1 million annually to help more than 500 architectural professionals and their families, and offers email and helpline support for those who have worked in the UK architecture field for at least one year.

Inside a culture of sacrifice

In 2017, the ABS and RIBA began collaborating to raise awareness about mental health issues for architecture students and professionals. In May 2017 and in March 2018, RIBA surveyed more than 2,100 UK architecture students on mental health. Melissa Kirkpatrick, an architecture student at the University of Sheffield, is writing a masters dissertation analysing the results.

Kirkpatrick says that students most often cite insensitivity from an instructor as a trigger for their distress. “One of the things that causes poor mental health is this culture within architecture, where students are expected to sacrifice for their art or their project, where it’s a competition of who is staying up latest and working hardest.”

The RIBA survey findings echo her own experience as an undergraduate. “I was never diagnosed with any mental health conditions, but definitely I and so many others were so, so stressed,” she says. “It was expected that you would be very, very stressed, and you had to be, and if you had a breakdown, then it’s normal and part of the design process.”

Designing a better balance

Kirkpatrick recommends that architecture schools hold mental health workshops for students, train teachers to encourage more positive communication with students and revoke 24-hour access to studio facilities – often touted as a perk by schools – to encourage work–life balance.

If those teaching the next generation of architects don’t change the culture, “students will take their bad habits and expectations of what life should be as an architect into their working lives and things will never really change,” Kirkpatrick says. “But it doesn’t have to be that way.”

About the contributors

Kristin Hohenadel

Kristin Hohenadel is an American writer and editor based in Paris. Her work has appeared widely in publications including the New York Times, Slate and Fast Company.