For Liz Carr, preparing for lockdown is not about stocking up on canned goods. She has to be ready to challenge a healthcare system that frequently puts Disabled people and anyone else labelled with "underlying health concerns" at the back of the queue to receive treatment.

Lying low for lockdown and beyond

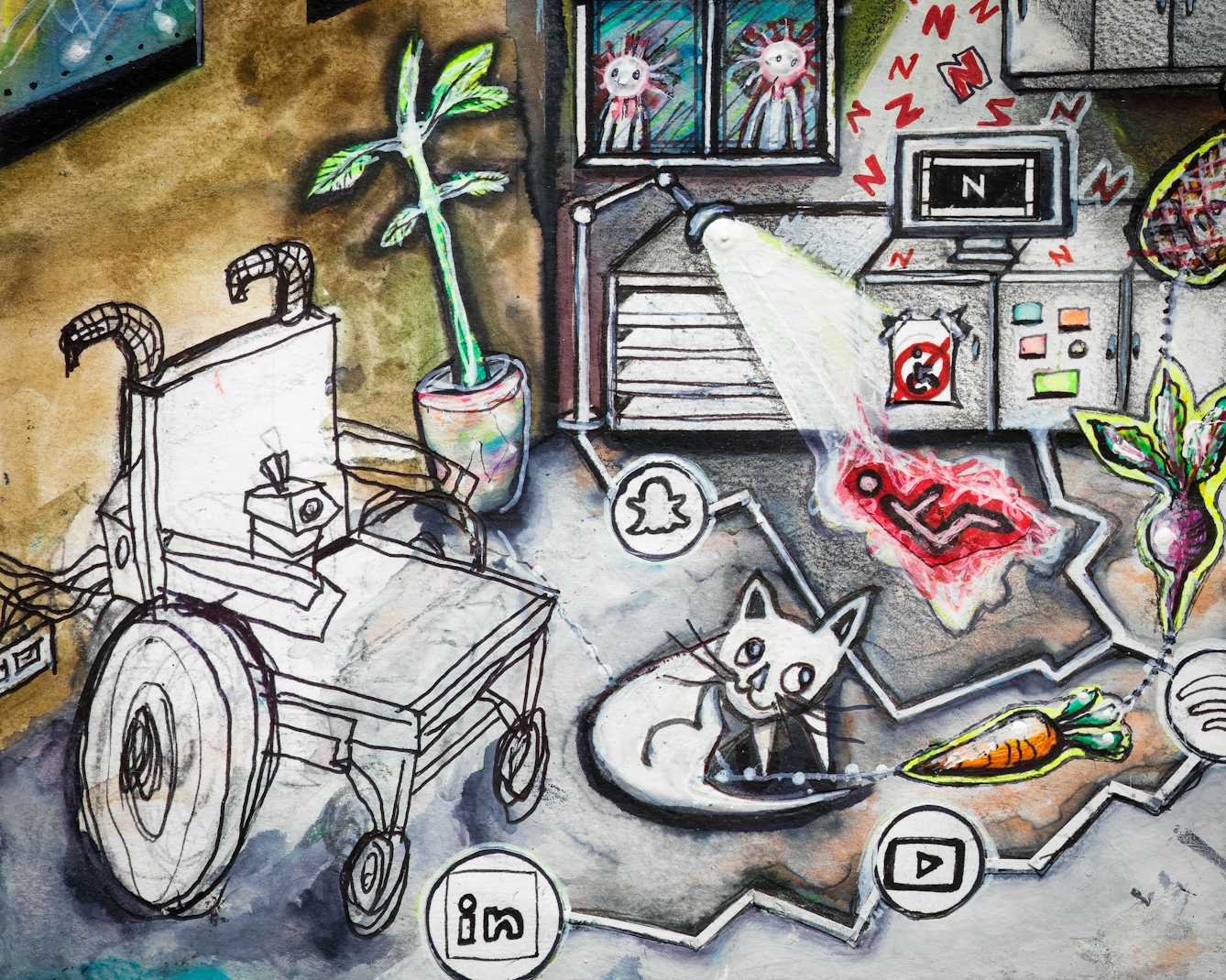

Words by Liz Carrartwork by Carrie Ravenscroftaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

On 10 March 2020 my consultant rang to tell me the hospital was replacing face-to-face appointments with calls and that I should avoid going there for the next three months. As a wheelchair-using Disabled woman with a potpourri of what are now ubiquitously known as “underlying health conditions” (UHCs), I asked him if I needed to be particularly careful. He replied that I should lie low for the next 18 months – or until there’s a vaccine.

Since then I have lived in lockdown as a voluntary shielder with my wife and our three cats. We have ventured outside the front door fewer than 20 times, and instead of nightly, my electric wheelchair has been charged only once. My shoes have become objects of nostalgia.

Anti-social distancing

The first time we left the house was a month into lockdown, when we decided a trip to the postbox would be good for our mental health. Everything was fine until we encountered other humans.

The first person was safely across the road, the second was masked, but as we approached the postbox, a third person walked briskly towards us, chatting away obliviously on his phone. He had no intention of moving out of our way. I was terrified. I had expected everyone to give me a wide berth — hell, as a Disabled person, I’m used to people normally doing a version of the Ministry of Funny Walks to avoid me. But not today.

My wife suddenly shouted, “Freeze and close your eyes!” I obeyed and waited for danger to pass

We were outdoor rookies with no idea what to do when other people don’t give you two metres of space. I had a wall to my left, a kerb to my right and nowhere to manoeuvre my wheelchair to safety. My wife suddenly shouted, “Freeze and close your eyes!” I obeyed and waited for danger to pass.

One man, Covid status unknown, wanders into our path and I’m left feeling ‘vulnerable’, as the government likes to define people like me. On returning home, I noted the then two-week virus incubation date in my Filofax and hoped I was going to be okay.

“The first time we left the house was a month into lockdown, when we decided a trip to the postbox would be good for our mental health. Everything was fine until we encountered other humans.”

Health passport to survival

From the first of the government’s podium briefings, Covid-19 deaths were being played down as mostly due to “underlying health conditions” (UHCs) in order to reassure the majority. But when, like me, you have one or more of these UHCs, this felt personal and frightening, and anything but reassuring.

That’s why, whether on the official shielding list or not, I and many of my Disabled friends chose to hunker down at home to try and avoid the potentially fatal droplets containing coronavirus.

Before the official lockdown even began, Disabled people were busy setting up survival networks via social media. Many of us worried about what would happen if we had to go into hospital and would not be allowed to have our friends, family or support staff to accompany and assist us.

So our networks shared templates of hospital passports, which detailed any health and social-care needs essential to share – plus a space for photos to remind the staff that the patient lying before them is far more than a diagnosis and the sum of others’ prejudices.

Eleven times more deadly

Personally, it’s not that I’m more likely to catch Covid-19 but instead that I’m concerned about how my unconventional body would respond to it. Someone with the nickname ‘Little Lizzy Sparrow Lungs’ is perhaps not best equipped to fight off a virulent respiratory virus.

From March to July 2020 almost three fifths of deaths from Covid-19 have been Disabled people.

Equally, my body has served me very well up to now, so perhaps it would just sniff off Covid if it came along? Maybe, but that’s not a gamble I’m prepared to take. And this decision felt vindicated when the Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures confirmed that from March to July 2020 almost three fifths of deaths from Covid-19 have been Disabled people. Even more pertinently, Disabled women are almost 11 times more likely to die from the virus than non-Disabled women.

“I have lived in lockdown as a voluntary shielder with my wife and our three cats. Instead of nightly, my electric wheelchair has been charged only once. My shoes have become objects of nostalgia.”

Ethics versus economics in healthcare

As a frail-looking 48-year-old woman in an electric wheelchair who requires 24-hour assistance, if I needed hospital treatment for Covid-19, what would my chances be of receiving the limited resources available?

Some Disabled people who use ventilators on a daily basis have been told that the machine’s essential filters will be prioritised for Covid-19 patients. When rationing becomes part of medical decision-making, I feel very unsafe. Concerned I would be denied a ventilator, I asked a friend of mine with sleep apnoea to order me a CPAP breathing machine, because I’d read articles about how to hack them to use as a DIY ventilator.

My fears were further fuelled when, in March and April 2020, guidelines were issued to assist doctors on the Covid front line with their treatment priorities. The British Medical Association ethics guidelines stated: “It is preferable to save the lives of three patients with high need and a high likelihood of benefiting than one patient with high need and a low – but nonetheless real – chance of benefiting. This is the heart of the moral challenge.”

Ethical guidelines felt more like economic ones, and it was clear doctors were going to be in the unenviable position of judging the value of a life. I was afraid of what medical conclusion they would make when faced with me.

The clinical frailty scale of treatment

Around the same time, initial guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) stated that on admission for Covid-19, all adults should be assessed using the clinical frailty scale (CFS). Usually reserved for older people, this scale rated those needing daily assistance as too frail for treatment. My inability to get dressed unaided placed me in this category.

This was so frightening for many Disabled people and our families that after an onslaught of campaigning, NICE clarified that these guidelines were not suitable for those with learning difficulties or stable conditions “like cerebral palsy”. Despite this clarification, I still fear that in the chaos of a Covid-19 hospital admission, unintentional bias, assumptions and rationing may inform decision-making.

“Ethical guidelines felt more like economic ones, and it was clear doctors were going to be in the unenviable position of judging the value of a life.”

The DNR as a symbol of health inequality

Inequality in healthcare feels as great a risk to many of us as the virus itself. In April a doctor’s surgery in Wales sent a letter to their “at risk” patients only, suggesting they sign a do not resuscitate (DNR) order so “scarce ambulance resources can be targeted to the young and fit who have a greater chance”.

The letter was withdrawn, but other examples include a similar letter sent to an autism support group by a Sommerset surgery and many sent to care homes, advising them to place blanket DNR orders on all their residents.

Doctors I hugely respect have tried to reassure me that DNR orders do not mean patients are being medically abandoned. Perhaps, but if that’s the case, why not place a DNR on everyone’s notes? Too many older and Disabled people have had DNRs placed on their records without their consent. To me, a DNR feels like a symbol – that some lives are valued less than others.

Evaluating human life and health

As the second wave washes over us, we are again seeing policy decisions that suggest differential treatment for those who contribute less economically while costing the state more.

Despite high death rates among care-home residents, hospital policy decisions have been reintroduced to again release Covid patients into care homes. But with a vaccine on the horizon, it’s a relief to see the government is recognising older people in care homes as a priority.

Unfortunately, Disabled people under 65 in care homes are not seen as a priority. Nor are those who have been shielding and unable to leave their homes for months on end.

I’ll never know if my attempts to reduce the risk of catching Covid-19 have been necessary or reasonable. But as long as I feel that my life and those of other Disabled and older people are not valued by those in power, then I will continue to do all I can to avoid becoming yet another “underlying health condition” statistic.

About the contributors

Liz Carr

Liz Carr is, among many things, a Disabled woman, an activist and an actor. She is perhaps best known for her role as Clarissa Mullery in the BBC’s forensic drama ‘Silent Witness’.

Carrie Ravenscroft

Carrie is a queer and neurodivergent artist from London. Her art practice focuses on women’s health, late diagnosis and the mind-body connection, which she communicates through colour, characters and symbolism in detailed, linked artworks. Recent creative projects include a neuroart exhibition in collaboration with neuroscientists at the Kings College ADHD Research Lab. Outside of making art, Carrie is a a mental health support worker and art psychotherapist at Mind, the mental health charity, and volunteers as a psychedelic first aider with the charity PsyCare.