St James’s Gardens, a former burial ground next to London’s Euston Station, closed in summer 2017 for work on the new HS2 rail line. Removing the tens of thousands of bodies buried on the site required the largest exhumation in British history. Tom Bolton explores some of the stories behind the now lost graveyard and the bodies it held.

By the late 18th century the graveyard of St James’s Piccadilly, a church designed by Sir Christopher Wren, had run out of space, like most in old central London. A plot of land was purchased next to the Hampstead Road, which was then out beyond the northern edge of London. It received its first coffins in 1788. Soon after, a chapel was built for the new burial ground. Designed by Thomas Hardwick, St James’s Chapel survives only in drawings and descriptions.

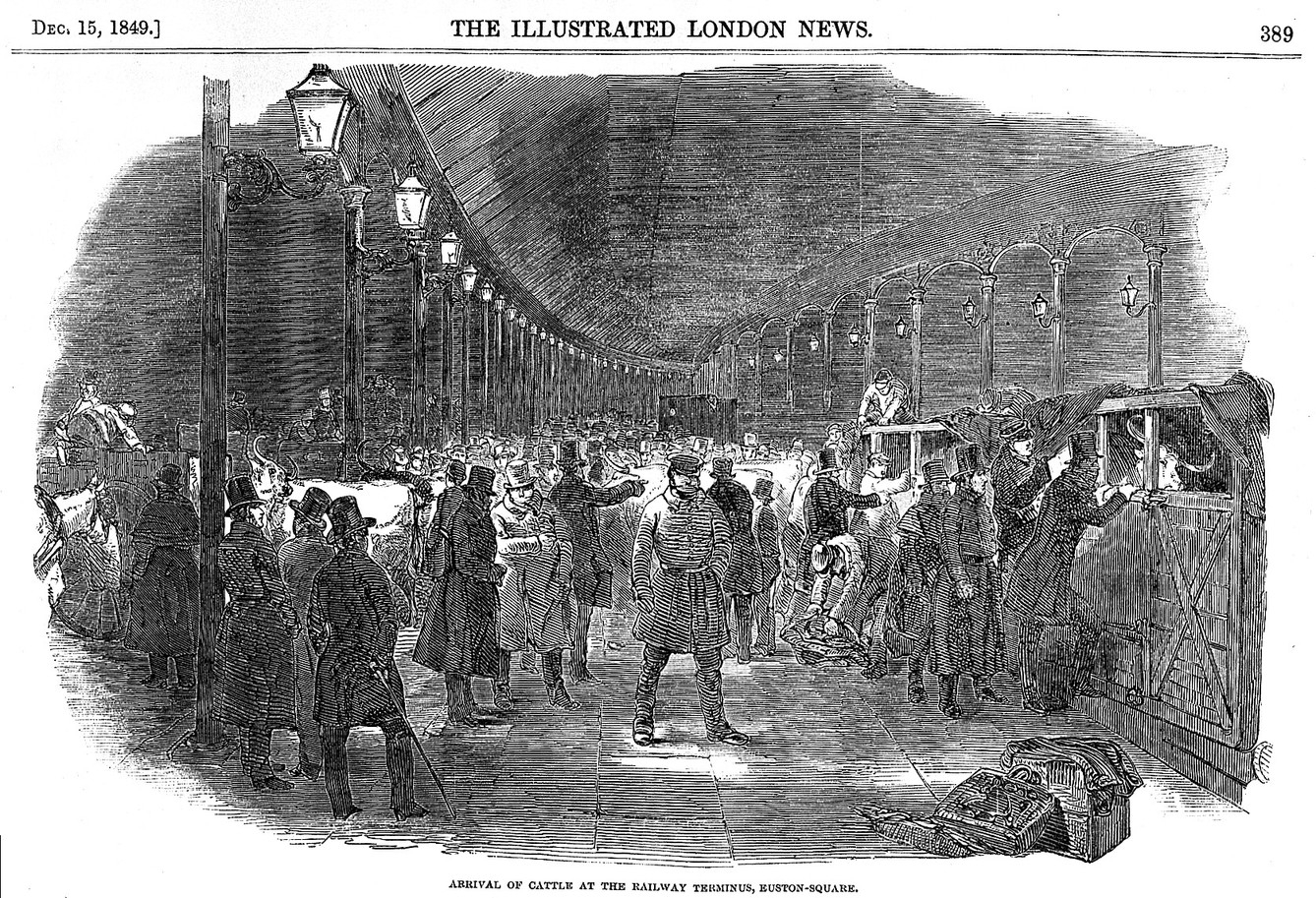

In 1852 the new graveyard was itself closed for burials. In 1871 St James’s Chapel became the church for a new parish – St James Hampstead Road – but it was close to busy railway lines into Euston Station from the Midlands. As Euston became dominated by the station and heavy train traffic, the surrounding area slowly began to decline. In ‘Old and New London’ volume 5 (1878), Edward Walford described the burial ground as “large, dreary, and ill-kept”. In 1887 it became a public garden, with the headstones cleared away to the edges – the reason so many graves in St James’s were lost.

When the digging started to prepare the site for High Speed 2 (HS2), all that was known was that somewhere under this patch of poorly maintained park there could be as many as 60,000 bodies. The Euston excavation was one of Britain’s largest ever digs, and has taken three years to complete, with the site covered by a 11,000 square metres of roof. The uncovered remains are now waiting for a decision on where they will be reburied.

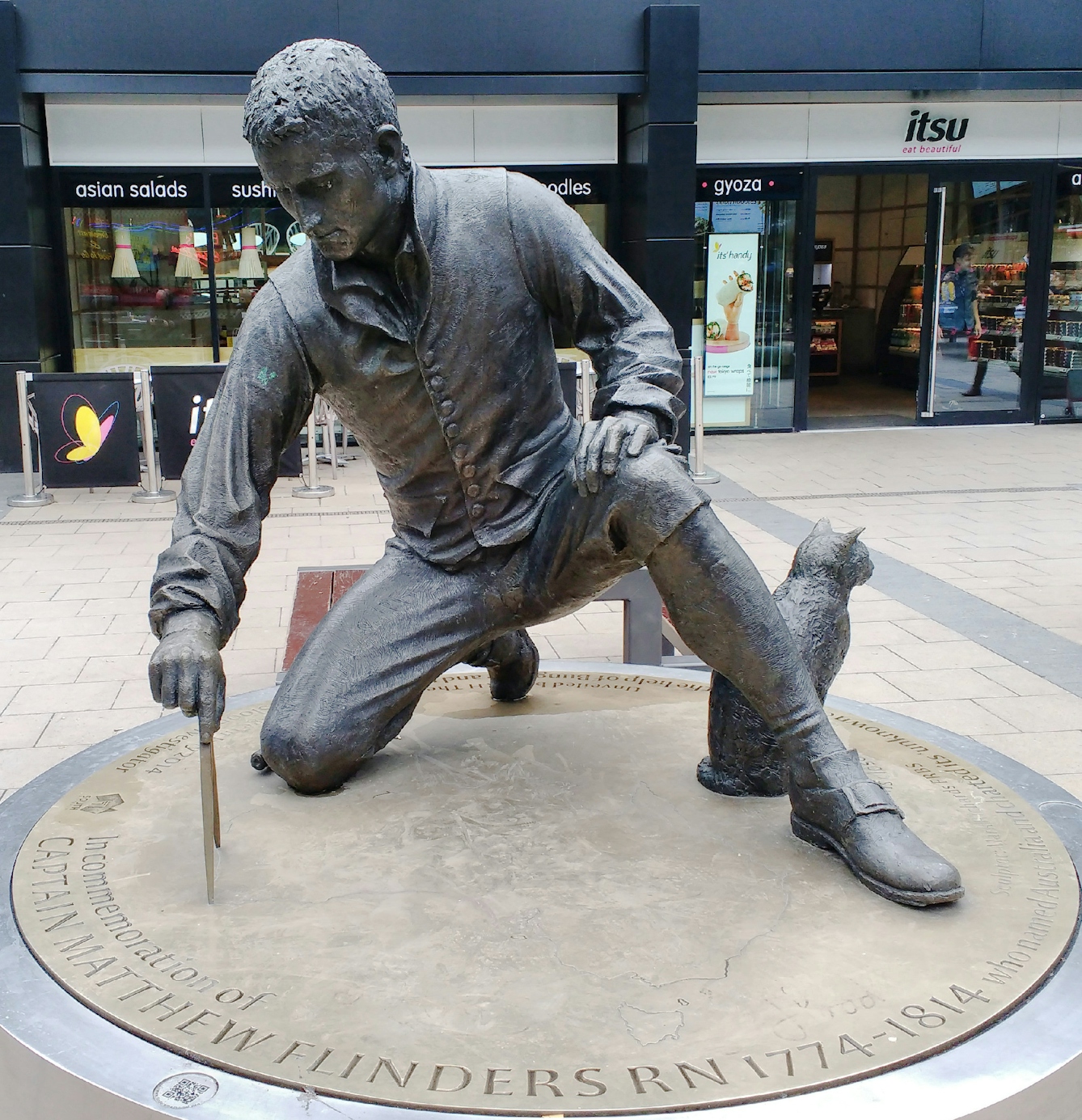

Euston had already claimed a slice of the burial ground when the station was rebuilt in the 1960s, and the long-lost grave of the explorer Captain Matthew Flinders was thought to lie under platforms 12 to 15. But in 2019 archaeologists found his coffin, lead nameplate still intact, under St James’s Gardens. Flinders was a Royal Navy captain inspired by ‘Robinson Crusoe’. He sailed around ‘New Holland’ and New South Wales between 1798 and 1800 in the company of the Aboriginal chief Bungaree. Together they discovered that the land was a continent, and Flinders proposed its name should be Australia.

While his name is famous in Australia, with the Flinders River in Queensland and Flinders Street in Melbourne named after him, Matthew Flinders isn’t well known in the UK. He died aged 40, barely making it home after six years in prison on Mauritius. He was interred in St James’s burial ground in 1814. In 1852 his sister-in-law found his grave gone and, she supposed, his remains “carted away as rubbish”, according to E Scott’s 1914 book, ‘The Life of Captain Flinders’. A statue of Flinders, and Trim his cat, now sits in the Euston Station forecourt.

Lost, but not so mourned, is Lord George Gordon, who was buried in a forgotten spot in St James’s Gardens. He was an MP and head of the Protestant Association, which was notorious for triggering the disastrous Gordon Riots of 1780 with rumours of a secret Spanish coup. A crowd of 50,000 people marched on Parliament with a petition against the Catholic Emancipation Act, then rampaged through London, burning prisons and the houses of Catholic people. In response, the army shot 285 people dead. Gordon died in Newgate Prison, and it is not known how or why he came to be buried at St James’s.

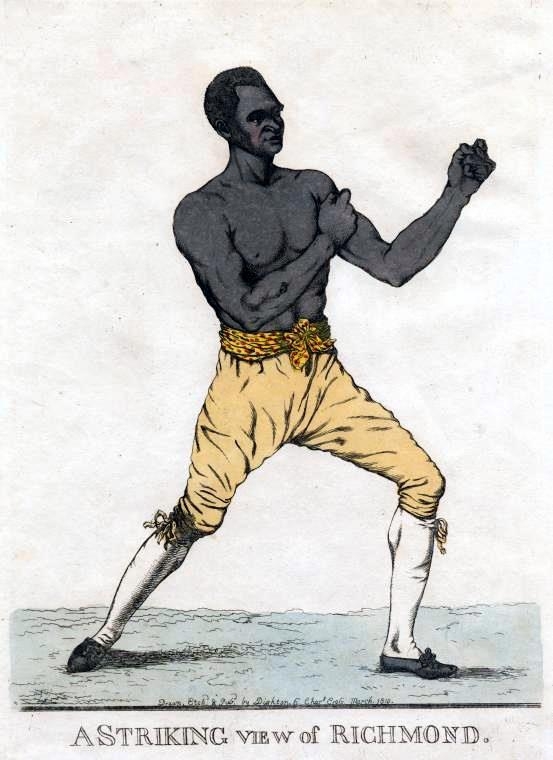

The boxer Bill Richmond is also thought to have been buried in St James’s Gardens. A Georgian celebrity, he was a Black man who was born a slave in New York. He came to England as a servant and married a white woman, which was extremely unusual for the time. Fighting bare-knuckled, he became famous as the champion boxer of his age. He was an usher at the coronation of George IV in 1821 and spent his last night drinking with Camden boxer Tom Cribb before his death in 1829.

The 18th-century radical Thomas Spence is also believed to be one of the 60,000 buried in St James’s Gardens. He was a reformer who campaigned for the right to vote for all, for children to be free from abuse, for an income for the unemployed, and for common ownership of land. His pamphlets earned him seven months in Newgate Prison. Brian Logan, director of the Camden People’s Theatre, staged a show about St James’s Gardens in 2019 called Human Jam. Logan pointed out that Spence has now been robbed of the only land he ever owned – his burial plot.

The Christie memorial was the finest in St James’s Gardens. It was a dark slate obelisk commemorating James Christie, the founder of Christie’s auction house, and his family. The memorial recorded that James’s son Edward, a midshipman on HMS Theseus, died of a fever in 1801, aged only 19, while on a captured slave ship in Jamaica. Also commemorated is Captain Charles Christie, who served in the Bombay Native Infantry but was killed fighting for the Shah of Persia at the Battle of Āṣlāndūz in 1812. When asked, HS2 told me that the Christie memorial is currently in storage, with a view to displaying it in future.

The London Temperance Hospital was built on part of the St James’s site in 1873. It was an alcohol-free hospital in a time when alcohol was a common part of the treatment for many illnesses, up to and including delirium. St James’s Chapel was demolished in 1964 and now the Temperance Hospital has also gone. It closed in 1990 and lay empty for a quarter of a century, becoming one of London’s most prominent derelict buildings. The open ironwork balconies, designed to let patients take the air, rusted slowly away. It was demolished in 2017.

In 2017 the vicar of St Pancras Church, the Reverend Anne Stevens, told the House of Lords High Speed Rail Bill Select Committee that she had a “particular concern for the dead” in St James’s Gardens. However, one of the committee members – Lord Brabazon of Tara – told her: “Over London as a whole, there would have been no developments at all if it hadn’t been possible to move graveyards or develop on top of them. They have been there for years, maybe. But when developments take place, they have to go.”

About the author

Dr Tom Bolton

Dr Tom Bolton is a researcher, and the author of five books, including ‘London’s Lost Rivers Volumes 1 & 2’, ‘Low Country: Brexit on the Essex Coast’ and ‘Vanished City: London’s Lost Neighbourhoods’. His work has been published in the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph and Londonist.