For two women wanting to share their different cultural backgrounds with their child, even choosing a sperm donor can get complicated. Paula Akpan explores the issues around fertility treatment and discovers that resources for lesbian couples are thin on the ground.

Getting to grips with fertility treatment is hard. Not only is the process itself, from consultation to embryo transfer, physically and emotionally gruelling, but it can yield feelings of inadequacy and frustration. In addition, there’s a huge financial burden, with the potential to rack up tens of thousands of pounds. It gets even harder if you’re in a lesbian couple looking to conceive.

When it comes to lesbian women seeking out fertility treatment such as IVF, the chances of the fertilisation working are fairly good. But according to ARC Fertility, an information resource about fertility treatments, there are a number of additional factors they have to consider. “Do both partners want the experience of carrying a baby? If so, the first decision is which partner will try first? The second is how will you choose the sperm?” Alongside this, if one partner isn’t able to carry the foetus, or simply doesn’t want to, but still wants to share a genetic connection with any of the couple’s children, how do they go about that?

For lesbian couples where the partners are of different heritages and want to share those roots with any offspring, a whole new crop of issues arise with very little research to lean on. As researcher and social worker Kendra Koeplin discovered, “Most of the literature... addresses the experiences of interracial heterosexual couples or white lesbians choosing to conceive.”

“Getting to grips with fertility treatment is hard... there’s a huge financial burden, with the potential to rack up tens of thousands of pounds. It gets even harder if you’re in a lesbian couple looking to conceive.”

The existing research doesn’t take into account the existence of mixed-heritage couples, who may share the same race but different heritage make-up, adding another layer of complexity. And she notes that until recently, research into gay families tended to conflate lesbian experiences with those of gay men – primarily white, middle-class gay men.

The importance of shared heritage

Jade and her wife, Naomi, have been together for nine years, after meeting at Pride in London back in 2011. While Jade claims Chinese Malaysian, English and Welsh heritage, Naomi hails from both England and Ireland. For both of them it was of paramount importance to share these parts of themselves with their child.

The couple decided that they wanted to select a donor who, as closely as possible, represented who they were – specifically Jade, as Naomi was the birthing partner. Jade explains: “We spent a really long time researching for donors via London and Europe, and then eventually looked to a Californian clinic which had a donor who was Chinese and American, with a bit of Scottish heritage, so it felt like a similar mix.”

“Finding a Black sperm donor is not straightforward... 71 per cent of sperm donors are white British, while only 2 per cent of donors are Black African.”

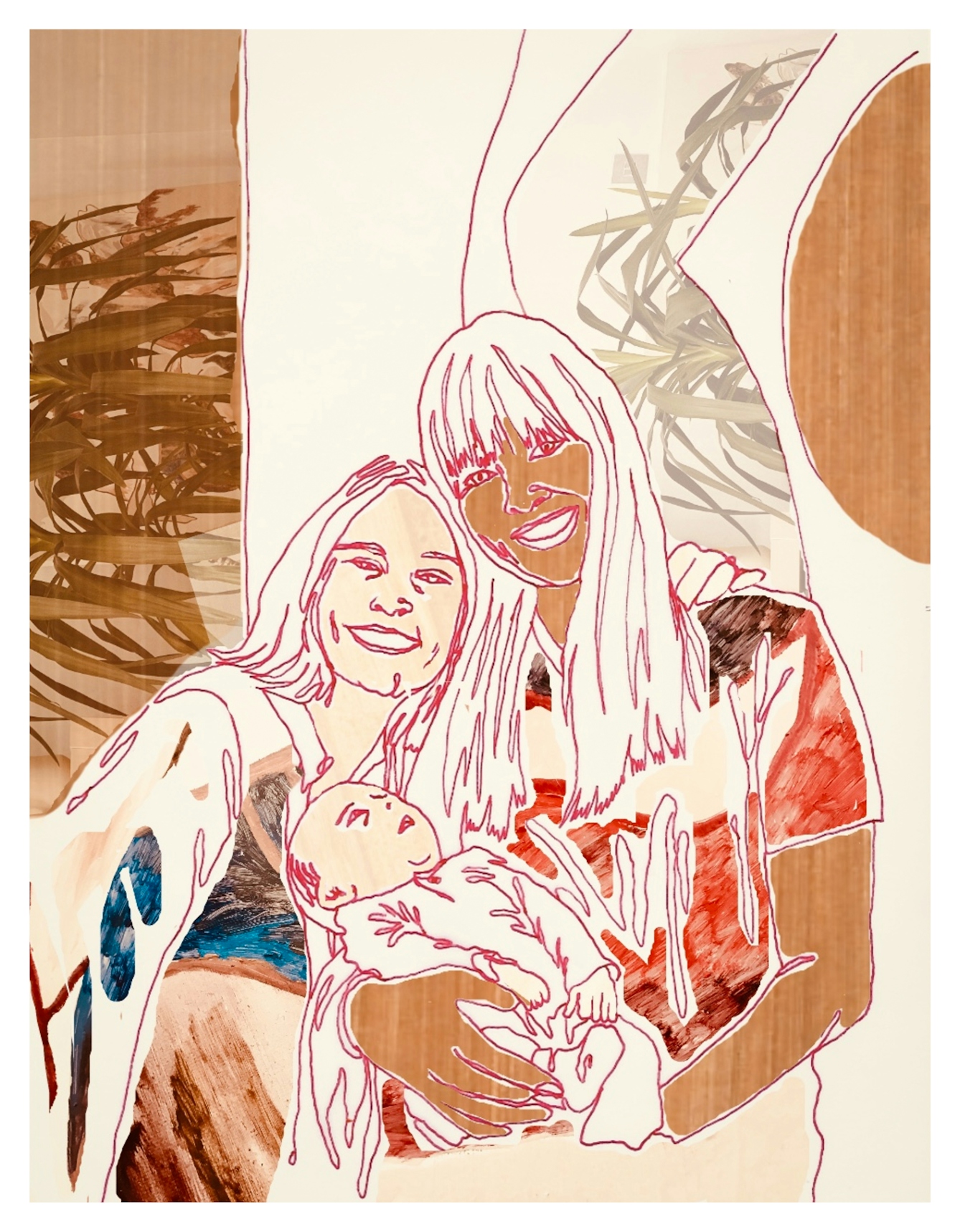

The result was their three-month-old son, Neo, who has an identity he can draw inspiration from. “Neo’s middle name is ‘Lee’, which is from my mum’s family name, and my mum refers to herself as ‘Popo’, which is the Chinese name for ‘grandma’,” Jade continues. “Naomi is very close to her Irish roots from her grandad and nanny on her mum’s side, and will take him to where they both grew up in Kilkenny when he’s old enough.”

For Dom, who is of Dominican heritage, and her Sierra-Leonean partner of four years, it’s a no-brainer to use a sperm donor of African-Caribbean heritage when they start treatment. As Dom plans to carry the baby, she believes sharing some sort of cultural bond is important for both her and her partner: “I think because one of us will not be biologically related to our child/children, there’s a sense of inclusion and unity, having sperm from our background.”

The scarcity of Black sperm donors

But finding a Black sperm donor is not straightforward. “Black sperm is very limited in the UK, so also cast your net wider outside of the UK,” Dom advises. The Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority’s 2016 report found that 71 per cent of sperm donors are white British, while only 2 per cent of donors are Black African. In 2018, Co-ParentMatch, a sperm-donor search tool created by a lesbian couple, reported that they were “struck by the high volumes of women searching for Black sperm donors” on their website.

“While Jade claims Chinese Malaysian, English and Welsh heritage, Naomi hails from both England and Ireland. For both of them it was of paramount importance to share these parts of themselves with their child.”

Leo*, a Black British Caribbean woman, is currently doing research and planning into fertility treatment with her white British partner. She describes it as “vitally important” for them to have a West Indian donor so that their future child is connected to their Black heritage, both genetically and culturally: “Even though [we’re] at the beginning stage, we know there’s a severe lack of West Indian sperm donors registered and available, which has prompted us to lean towards finding a donor ourselves and through our personal network.”

It’s clear that sharing heritage with future children plays a huge role in decision-making, in some instances determining who carries the foetus to term and how couples find a donor, whether through a fertility clinic or by themselves.

What is also evident is how much research these couples need to do on their own. Resources and guidance on fertility treatments for lesbian couples are few and far between, let alone specific advice for mixed-heritage lesbian couples. As Leo says, “An accessible resource or community of parents and couples similar to us who have gone through the process would be invaluable.”

* Leo’s name has been changed to protect the identity of the interviewee.

About the contributors

Paula Akpan

Paula is a journalist and public speaker. A sociology graduate from the University of Nottingham, Paula’s work mainly focuses on Blackness, queerness and social politics, and she regularly writes for a variety of publications including Vogue, Teen Vogue, the Independent, Stylist and more.

Miranda Forrester

Miranda Forrester is an artist and painter. Her work has been featured in several London exhibitions, including at the Mall Galleries, Christie’s Education and the Copeland Gallery. Her practice explores the queer Black female gaze, and investigates how her paintings can rearticulate the language and history of life drawing through a queer Black feminist desiring lens, and in doing so, depict what the male gaze cannot see.