In desperate need of a warm bath to ease her pain, Abi Palmer found herself sharing a tub with a strange, viscous slime. Repulsed, she was also fascinated by her iridescent bath mate and what it could teach her.

It was winter when I finally finished writing ‘Sanatorium’, a memoir exploring the experience of floating. As my editor and I emailed revisions back and forth, the weather became very bitter. I developed an aching cold in my legs that could only be soothed by sitting in a warm bath.

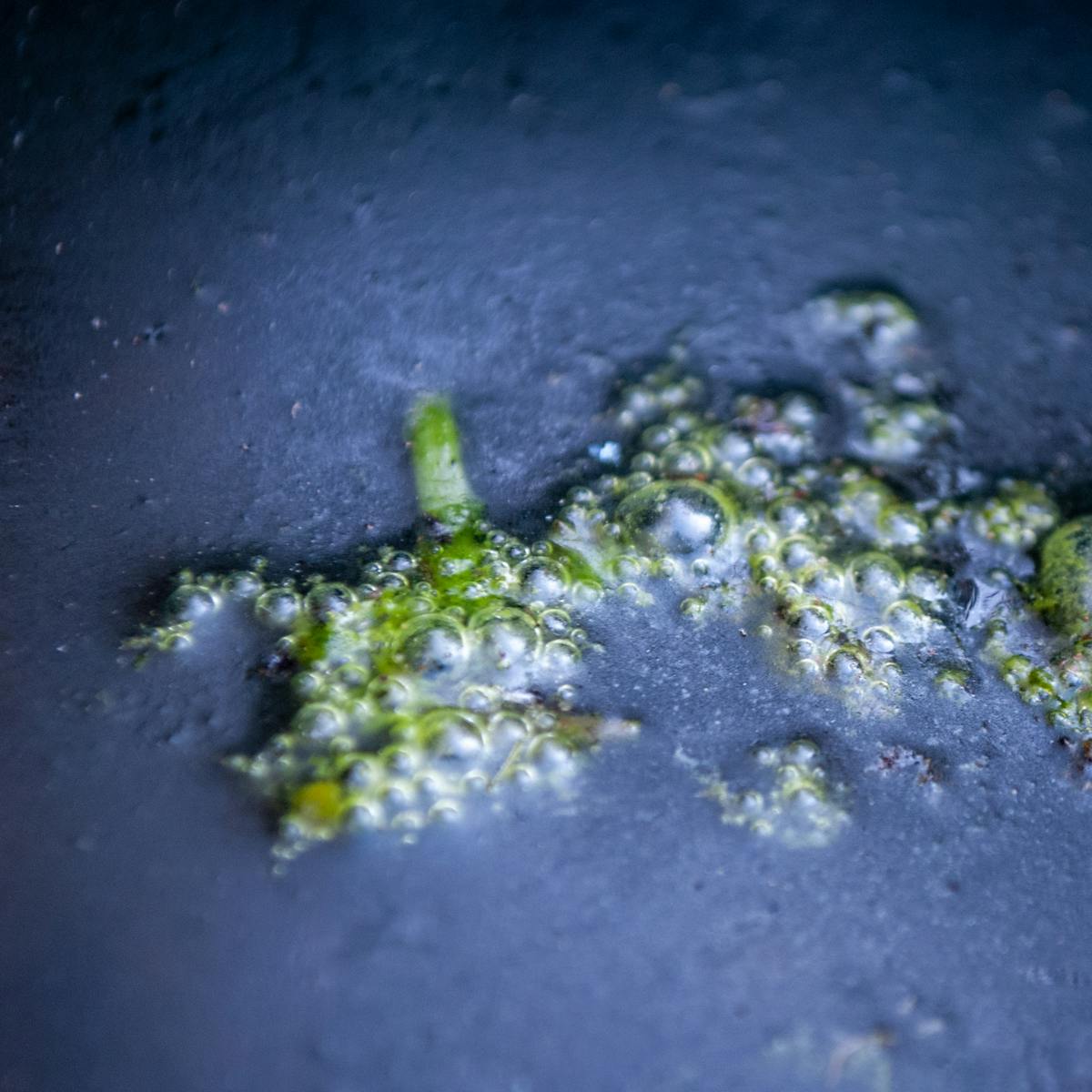

My book’s muse – a baby-blue inflatable bathtub – sat, deflated, in the corner of my bathroom. I pressed my lips to the tub’s rim to reinflate it, when I noticed that it was covered in a layer of grey slime.

It looked like the viscous liquid that slugs make to copulate. It slid between my fingers and formed webby strings. I searched my bathroom in vain for the creature that had created this monstrosity.

My eyes widened. I realised, with a jolt, that the slime was coming from the tub itself.

I was probably around two parts repulsed to one part fascinated by this new horror. I fetched a cloth but felt guilty about wiping it away. As a member of the disabled community, I’m acutely aware of being regarded by some as too distasteful to exist.

"The baby-blue bathtub was covered in a layer of grey slime. I searched my bathroom in vain for the creature that had created this monstrosity."

I was also in a lot of pain, too fatigued to do anything properly. I squirted some Fairy Liquid around the edges of the tub and hosed it down. Then I ran myself a bath.

The secret life of slime mould

Biologically, slimes are diverse. They can be bacterial, fungal, or more complex organisms known as slime moulds.

Prominent slime moulds sound playful and absurd, with pet names that could come straight from my own online community of queer crip shitposters: Caca De Luna (Moon Poo), Dog Vomit and The Blob, a slime mould with almost 720 different sexes. I’m already sold.

When well fed, cellular slime moulds are able to live and operate as a solitary amoebae. But when food is scarce, individual slime cells will seek out multiple partners. Once they have joined forces, they form a multicellular mass that thinks, operates and moves as one.

In their mass, the cells reconfigure themselves, forming stalks to produce fruiting bodies. These are picked up and transported in the wind. Once they have been spread, they begin life again as a single-celled organism. The individual cells that formed stalks die before they are able to reproduce, sacrificing their individual lives for the survival of the greater slime mass.

"Biologically, slimes are diverse. They can be bacterial, fungal, or more complex organisms known as slime moulds."

Other forms of slime move and communicate in equally fascinating ways. Acellular slime moulds can be remarkably efficient at finding and signalling to each other when divided – so much so that their movements have been found to mimic the shape of rail networks, travelling towards each other through the fastest, most direct connection.

I think about the queerness of slime mould, its cripness. I think about the many differing forms of otherness that exist within marginalised communities, and the subtle and innovative ways we find to signal to one another – the great lengths we will go to to find connection.

I think about the remarkable transformations that can take place when we find each other, the intimacy and trust placed in mutual aid networks. I think about our tremendous chosen families. And I think about the sacrifices made by community elders, so that future generations may experience something better.

It can be very hard to imagine a future if you don’t conform. There are so few representations of disabled and queer communities in a media that deals primarily in neat, white, abled story arcs, ending, for the most part, in heterosexual marriage and childbearing.

"I think about the queerness of slime mould, its cripness."

What if slime moulds were pointing towards a different way of being: something softer and more transformative? Instead of cringing away from a texture I am told is terrible and wrong, what would happen if I marvelled at its iridescence?

Of course, it’s always more complicated than that. Slime comes in many forms. As my bathtub filled with water, I read an article about a strain of slimy bacteria often found in bathtubs that is “probably okay” unless you’re immunocompromised.

As an immunocompromised person, quite frankly, I am exhausted by the handling of my own potentially catastrophic health outcomes as a side note or afterthought. But anyway, I decided to risk it: when you are cold and in pain, there are very few compromises you would not make to warm yourself.

Bathing together

The water in the bath was running clear. There was just a faint shimmer, like air vibrating on a very hot day. I had to fold the deflated rubber rim over to make it stand up properly. The smell was a mixture of hot plastic, washing-up liquid and sick.

I climbed in, water still running. The vomit smell was really very strong. I traced my fingers over the edges of the tub and found that the walls were still coated in slimy patches. I sat very upright in the middle, trying not to touch anything.

"What if slime moulds were pointing towards a different way of being ... what would happen if I marvelled at its iridescence?"

Tiny trails of mucus rose and drifted through the water, like snow. I didn’t know if they came from me or from the bathtub, or whether we were all the same, oozing substance. It struck me as somewhat poetic that my bathtub should be an improbable granter of life.

I pictured the bathtub taking over my body, sliming into my veins, turning my organs to mush and goo.

I got out more quickly than usual. I was too tired to rinse my body but, rather pointlessly, washed and sanitised my hands. As I lay in bed that night, I pictured the bathtub taking over my body, sliming into my veins, turning my organs to mush and goo.

Whatever it was, the slime was not fatal. But it did transform my relationship with the bathtub. Eventually I couldn’t stand the smell any longer. I threw the entire thing away.

And still, I find myself rooting for the idea of it. I picture my slime in a post-apocalyptic landmass, crawling towards its kin, inflatable bathtub still connected. I want to learn from it, to become part of it, even. I want it to keep transforming. Progress is an amorphous, many-gendered blob. I am dreaming of a slimy future.

About the contributors

Abi Palmer

Abi Palmer is an artist and writer exploring the relationship between linguistic and physical communication. ‘Crip Casino’ – her interactive gambling arcade parodying the wellness industry and institutionalised spaces – has been exhibited at Tate Modern, Somerset House and Wellcome Collection. Her debut book ‘Sanatorium’ (Penned in the Margins, 2020) is a fragmented memoir, jumping between luxury thermal pool and blue inflatable bathtub.

Bella Milroy

Bella Milroy is an artist and writer based in her home town of Chesterfield, Derbyshire. She is continually motivated by concepts of public and private spaces, and where the sick and/or disabled body exists within them. These concerns find themselves emerging in many aspects of her work, particularly within the collaborative projects she engages with, such as ‘Soft Sanctuary’, an ongoing programme commissioned by the Human Library Project for Sefton Libraries. You can find her most recent exhibited work in the show ‘Present State Examinations’, hosted by Turf Projects.