The launch of the NHS in 1948 had been a rousing success. But Aneurin Bevan’s promise that the NHS would be “free at the point of need” would, in the 1950s, be the root of the service’s first major crisis.

Fees, funding and the NHS

Cal Flynaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

Reluctance from GPs and consultants had been overcome, a new administration had been put in place, and the general public had hurried to make use of their new health service. Many finally had the opportunity to visit a doctor or dentist for the first time in years, having previously abstained due to financial constraints. In its first year, the new NHS provided patients with 27,000 hearing aids, 164,000 surgical and medical appliances, 6.8 million dental treatments and 4.5m pairs of glasses.

But by 1950, there was a growing fear among politicians in both major parties that opting to make the service entirely free may have been overgenerous, and would lead to spiralling costs.

It was true that initial spending had been far higher than forecast: in its first year, Bevan had to seek an extra £53m from the Treasury, nearly a third more than his original estimate. In March 1950, he would be forced to request a supplement of £100m, roughly half the entire education budget.

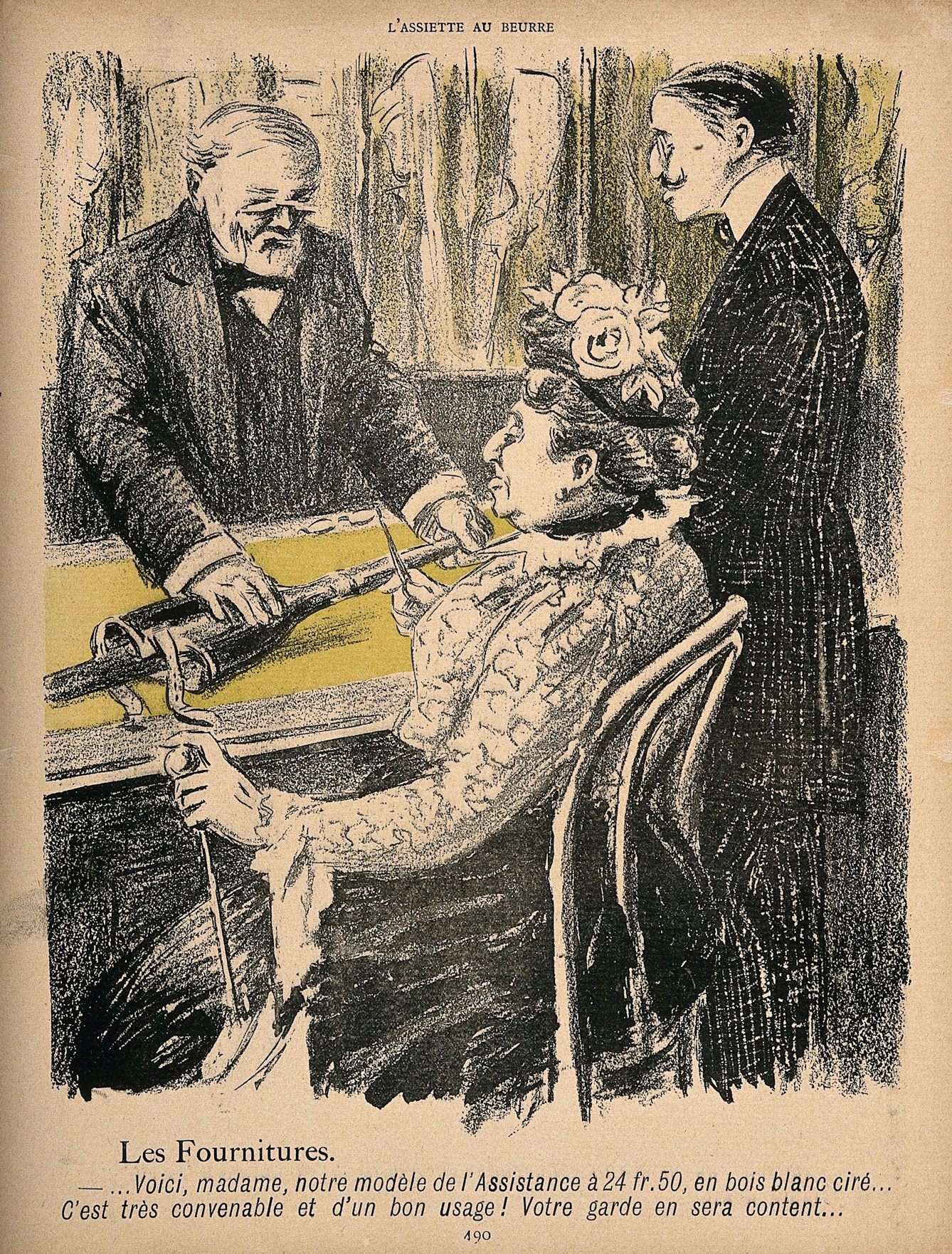

Even before the NHS was established, satirists illustrated the fear that subsidised healthcare would drive up demand from people who were not really in need.

The funding battleground

Bevan argued that the spending was a necessary correction after years of war and inadequate healthcare, and that it would stabilise over the coming years (a prediction that was borne out in the 1950s), but the apparent profligacy in the NHS resulted in mounting dissension in the Cabinet, as other ministers felt their own budgets squeezed.

Bevan’s biggest adversary was Hugh Gaitskell, an economist and a junior minister in the Treasury who was growing in influence in the Attlee government. Gaitskell pushed hard for NHS spending to be capped, and soon called for the introduction of charges for some aspects of the health service, partly to produce income and partly to stem demand.

He and Bevan developed a deep personal animosity: both considered the issue of fees a matter of principle – Gaitskell for, Bevan against – and it became a proxy battle, a clash between representatives from either end of the Labour political spectrum.

In 1950, this would all come to a head. The situation for the government was looking poor: it had a majority of just six seats, and in June the Korean War had broken out. After some hesitation – and exhausted by World War II – the UK agreed to support the US in sending troops and in undertaking an expensive rearmament programme. Then, in October, the Chancellor, Richard Stafford Cripps, resigned through ill health. Gaitskell was promoted to replace him – and he immediately set about using his new powers to force the issue of fees.

In pictures

By 1950, in Scotland four times as many people as predicted sought NHS opticians’ services. In England and Wales 5m sight tests were performed and 7.5m pairs of spectacles were dispensed.

A million sets of dentures were distributed in the first nine months of the NHS. There was huge demand to remove rotten teeth, and people who had very old sets finally sought replacements.

Inhalers, such as this one by Rybar and one by Brovon, were available on the NHS and advertised in the British Medical Journal (just over the page from advertisements for Player’s No. 3, “the quality cigarette”).

From the introduction of the NHS until 1975, people bought stamps to prove their National Insurance contributions and show their eligibility for the benefits of the new welfare state.

Sick-bed summits

Stafford Cripps was not the only government figure suffering from poor health. The following March, the Prime Minister himself was admitted to hospital with a duodenal ulcer, a stress-related condition, and in his absence the acting leader Herbert Morrison unwisely allowed a Cabinet vote on fees.

It approved Gaitskell’s plan to introduce charges for NHS spectacles and dentures, with the proceeds to go towards the defence programme.

All hell broke loose. Attlee’s hospital bedside, in the Lindo Wing of St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, became a fitting backdrop to frantic meetings over the future of the health service.

Despite pleas from doctors to spare Attlee worry, first Morrison arrived, then an outraged Bevan with his ally Harold Wilson, both of whom threatened to resign. Finally, Gaitskell himself arrived, also now threatening to resign if Attlee backed Bevan. Attlee, facing an impossible situation, would always maintain that had he not been in hospital, the whole farrago could have been avoided.

Nevertheless, Gaitskell got his way and the introduction of charges was announced in his Budget the following day. “WILL MR BEVAN RESIGN?” thundered the Guardian. It added, in subheading, that the “controversy over NHS charges might bring down [the] government”. So it would prove.

Aneurin Bevan died in 1960. But the Labour Party returned to government under Harold Wilson four years after that. Wilson made the abolition of NHS charges a key election pledge, and kept to his promise once in power – but the economic downturn of 1967 soon forced him to back down and they were reintroduced in 1968, albeit with exemptions based on age, income and ill health.

Years later, following devolution, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland would end prescription charges for good – but in England they still exist, at £8.80 per item.

Value for money

Spending did stabilise in the 1950s, as Bevan had predicted, and a committee chaired by the Cambridge economist Claude Guillebaud concluded that the service was efficient and cost-effective; if anything, Guillebaud said, it needed more money. So the Conservative government was put off restructuring it and rethinking the funding model.

“People hadn’t all been cheering when the NHS first came into existence – there had been a bit of anxiety before it had arrived about it how it would work,” says George Gosling, a historian of medicine at Wolverhampton University. “But very quickly people settled into it. They got attached to the idea of being able to go to the doctor whenever you needed, for free – so there was a sense that people had come to like the new system, and didn’t want to lose it.”

Faces of the NHS: 1950s

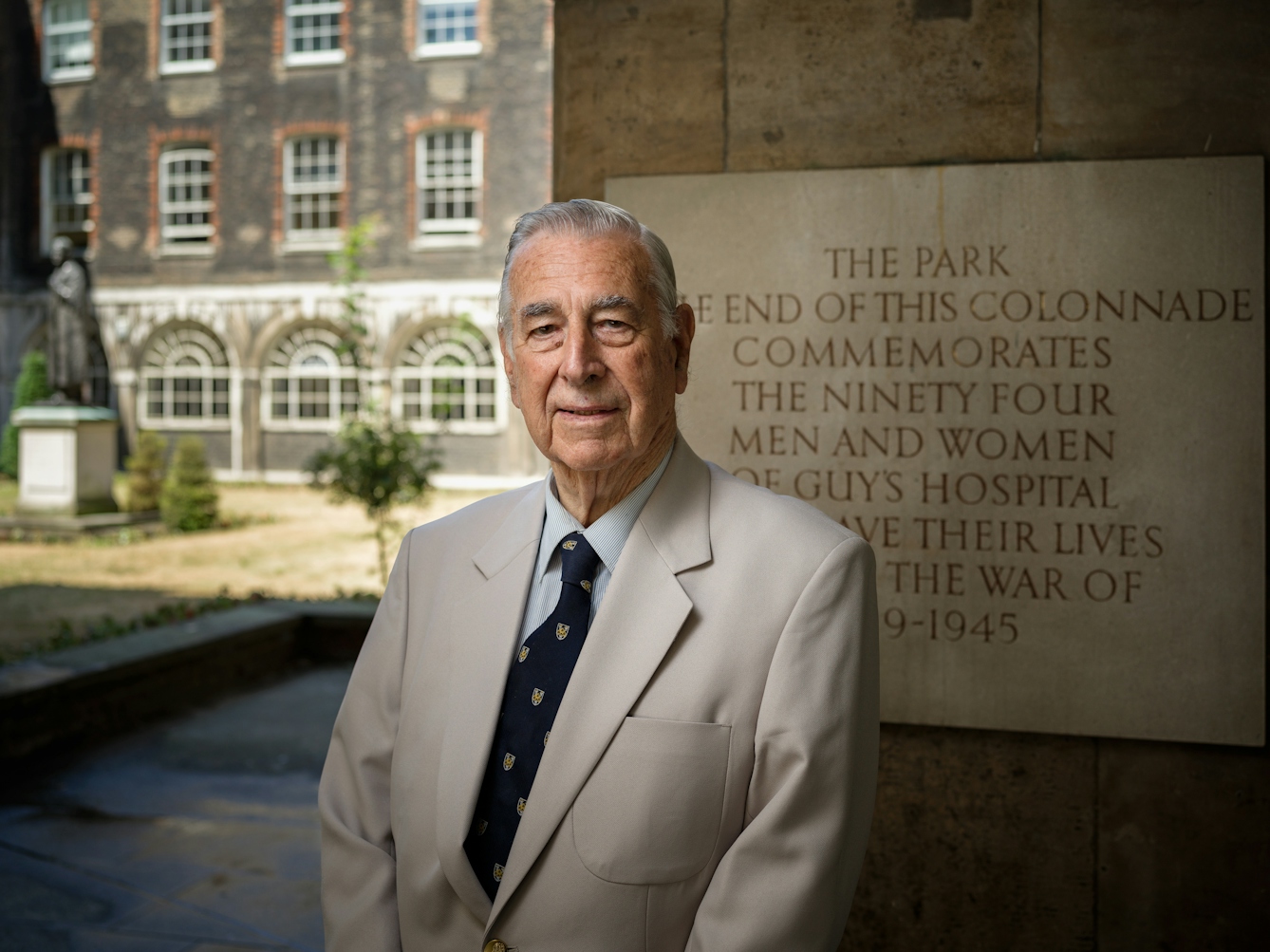

Morgan David Enoch began working for the NHS in 1954 when he qualified as a psychiatrist. He has experience of funding challenges, recalling that psychiatry was often not adequately funded. He can relate to current NHS staff: “As I look upon the NHS today, I want to be sympathetic and fair. There's been terrific growth... new innovations, new drugs, the costs have really increased massively, and therefore I understand the difficulties.”

Leslie John Cheeseman worked as a dentist for the NHS in the 1950s. For him, finances were a frustration of working with the NHS. Dentistry was the first branch where charges were introduced – but they didn’t always cover dentists’ costs. Still, he says, “I never refused any patient at all… I never said I won’t provide dentures… I won’t do crowns… Not all items of service are economic to do… [but] whatever anybody needed clinically, I provided. And I am quite proud of that, actually.”

Medical photographer Ray Phillips found his work with the Royal Free Hospital on innovative studies of diseases of the liver especially rewarding “because we built up a relationship with some patients, they got to know us well and also, strangely enough… they were able to lose their inhibitions, which was quite remarkable”. He notes that his work for the NHS has been “extremely satisfying and very, very rewarding – if not financially!”

The unquenchable thirst

Nevertheless, the question of funding has never really gone away. NHS spending, though still lower per capita than in countries like the US, Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands, has risen steeply since its earliest days – from 3.5 per cent of GDP in 1950/51 to 9.8 per cent of GDP in 2014, an increase of more than tenfold in real terms.

Despite this, the health service today finds itself in a serious financial crisis. In 2018, NHS trusts are on course to run up a combined deficit of £5.9 billion, as an ageing population and long-term illnesses related to lifestyle puts them under unprecedented pressure. Diabetes is now thought to consume 10 per cent of the entire NHS budget of £116bn.

Is it too generous to offer free medical treatment “at the point of need”, no matter the cause? Should those with lifestyle-related illnesses contribute towards, for example, the costs of gastric-band operations or the treatment of alcoholic cirrhosis?

All these questions are the continuation of a debate that began in 1951 and is still relevant today.

About the contributors

Cal Flyn

Cal Flyn is a writer and reporter from the Highlands of Scotland. She writes across the British press, including the Guardian, the Sunday Times, the Daily Telegraph, Prospect and New Statesman. Her first book, ‘Thicker Than Water’, was published by William Collins in 2016, and selected by the Times as one of the best books of that year.