What schools should say about sex has been a fraught subject for decades. Hannah Elizabeth looks at what information teens find about “the birds and the bees”, in the classroom and beyond.

Getting around the rules of sex education

Hannah J Elizabeth

- Story

With the 30th anniversary of the passing of the now infamous Section 28 into legislation this May, the sex education of our teenagers has recently been hitting the headlines again. The discussion of what we should and shouldn’t teach our teens in and out of the classroom never really goes away, and legislation such as Section 28 is just one example of an attempt to create rules regarding what information on sex and sexuality is available to children and teens. But how effective was legislation like Section 28 at making certain subjects unspeakable? And what happened outside the classroom?

Morris Gleitzman’s 1990 book ‘Two Weeks with the Queen‘ provided teachers with a way to address AIDS and homophobia outside of sex education classes.

Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Bill prohibited local authorities from promoting or publishing materials that promoted homosexuality; promoting the “teaching in any maintained schools of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship by the publication of such material”; and the giving of financial assistance to any of the above. Though not technically banning teachers from discussing homosexuality, it was interpreted by many at the time (and is remembered by many now) as a prohibition on any teaching about homosexuality in schools. It effectively silenced teachers, whose authority over curriculums became increasingly precarious as legislative changes across the 1980s and 1990s gave more power to parents, school governors and the government.

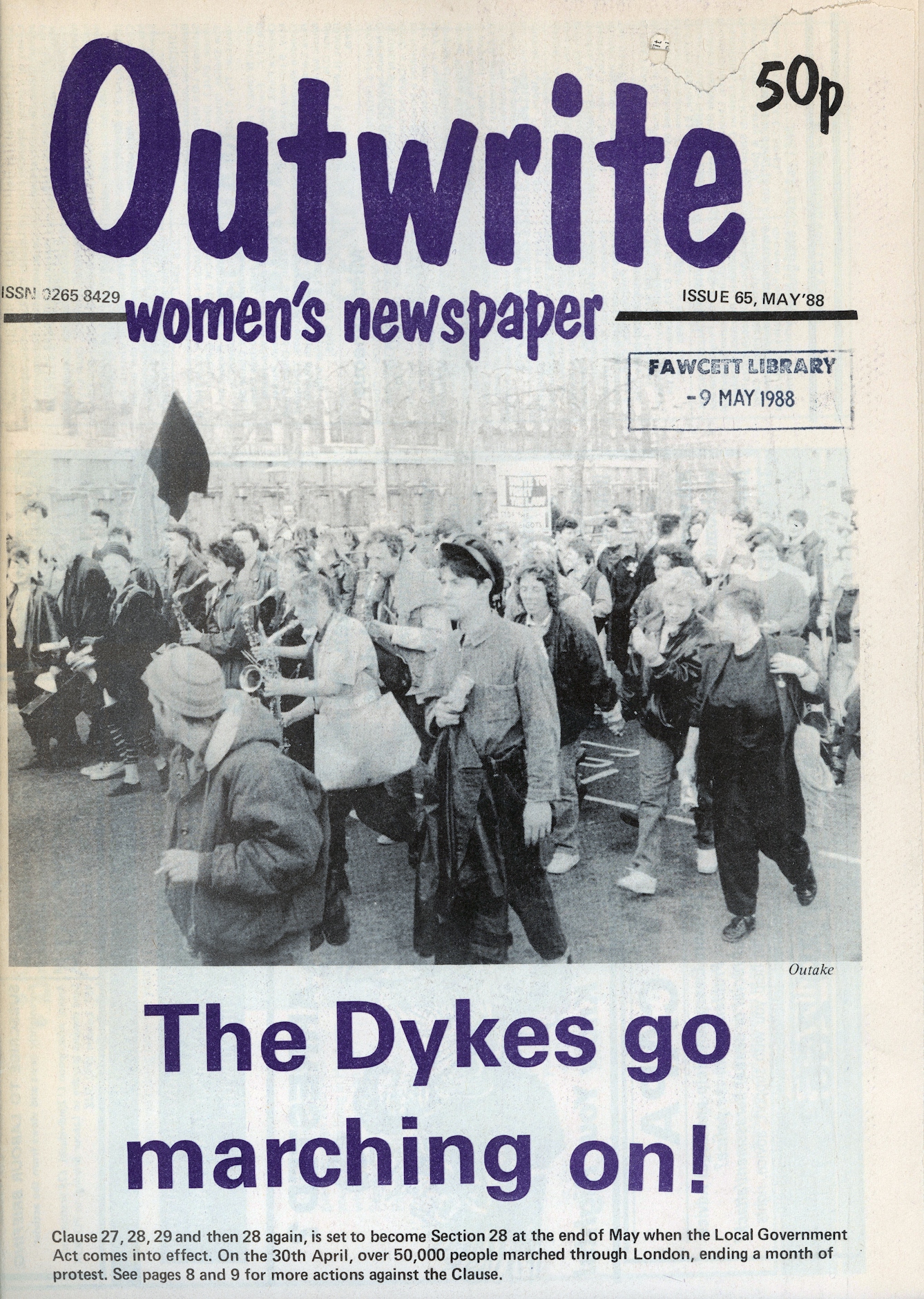

Section 28 protests

Many groups took to the streets and created protest materials such as flyers, magazines and posters to lobby against Section 28 and its implementation.

'Smash Clause 28! Fight the Alton Bill!' is a 1988 single by Chumbawamba. It was a benefit record for the London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard and the Women's Reproductive Rights Campaign.

Protests against Section 28 continued after its passing. This image is from July 2000: a drag queen blocks a bus operated by the Stagecoach company in Albert Square, Manchester, during a Stonewall rally. In protest at Stagecoach’s owner Brian Souter’s high-profile support of the legislation, activists have stopped the bus and daubed “28" on its windscreen in huge red characters, which they subsequently washed off in order to avoid arrest for criminal damage.

The thing is, while we should remember Section 28 and be weary of its persistent effects, teachers may not actually have been as silent on the subject of homosexuality as this legislation intended. Education legislation is hard to enforce day-to-day in the classroom, and while funding for materials on homosexuality was kyboshed, money for HIV/AIDS education – which often tackled homophobia head-on – was not. Section 28’s shadow and the parental right to withdraw their child from sex education lessons (which still exists today) might have made teachers careful about what they’d admit to teaching, but the availability of limited funding for anti-stigma AIDS education allowed some teachers to circumvent sex education policy that they found distasteful or unworkable, slipping anti-homophobia lessons in under the less controversial label of AIDS prevention.

A wonderful example, among many, is the 1990 children’s novel – later turned into a play – ‘Two Weeks with the Queen’, which tackled AIDS and homophobia with sensitivity and humour. Not only did the novel turn up on reading lists and in school libraries while Section 28 was still in effect, but it ended up on Key Stage 3 English Literature curriculums: students were taken to see the play, and numerous lessons and teaching materials for the classroom were generated around it.

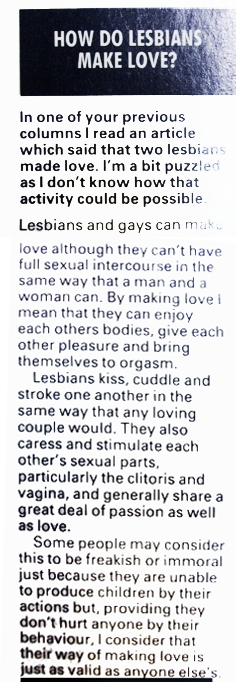

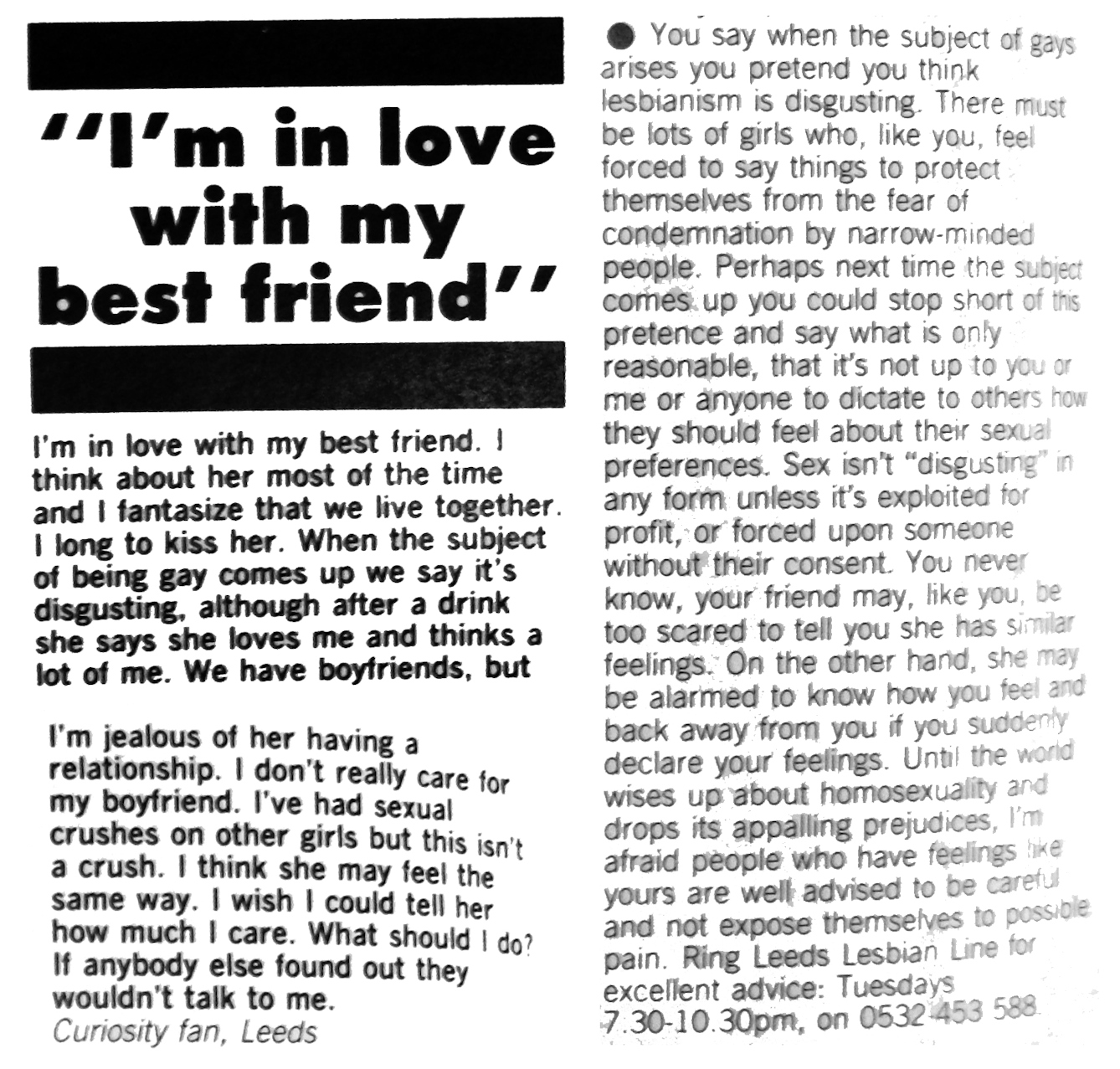

A MIZZ magazine agony aunt explains to readers how lesbians can have sex, emphatically stating that their way of making love is as valid as anyone else’s.

Outside the classroom, teenagers with a little money – or a friend or sibling with a little money – could access fairly explicit sex education through the health and problem pages of glossy teenage magazines – without the need of a rebellious teacher or parental consent. Launched in the early 1980s, new teenage magazines such as MIZZ and Just Seventeen enjoyed huge circulation figures.

These magazines, while often suggesting homosexual desire in teenagers was perhaps a ‘phase’, nonetheless presented it to teenagers as a natural and enjoyable part of the human experience, defending a teenager’s right to sexuality and answering questions like, “How do lesbians make love?” frankly (albeit often a little clumsily) and without condemnation.

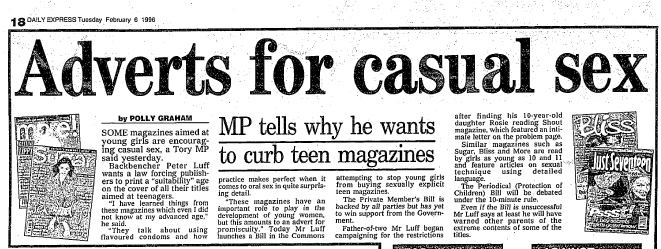

The explanation of sex acts, and what potential dangers they might carry, formed a substantial part of the discussion on the health and problem pages of these magazines – indeed, this content was a mainstay before and after the passing of Section 28. The openness of teenage magazines eventually caught the attention of the tabloid press, resulting in a minor moral panic, a (failed) bill put forward by Conservative MP Peter Luff to place age limits on teenage magazines in 1995, and the creation of the Teenage Magazine Arbitration Panel – an industry body that monitored the sexual content in teenage magazines.

Problem pages

Advice columns encouraged teenagers to be more open in their discussions of sexuality with their peers, and provided contact details for local phone lines that could offer further support.

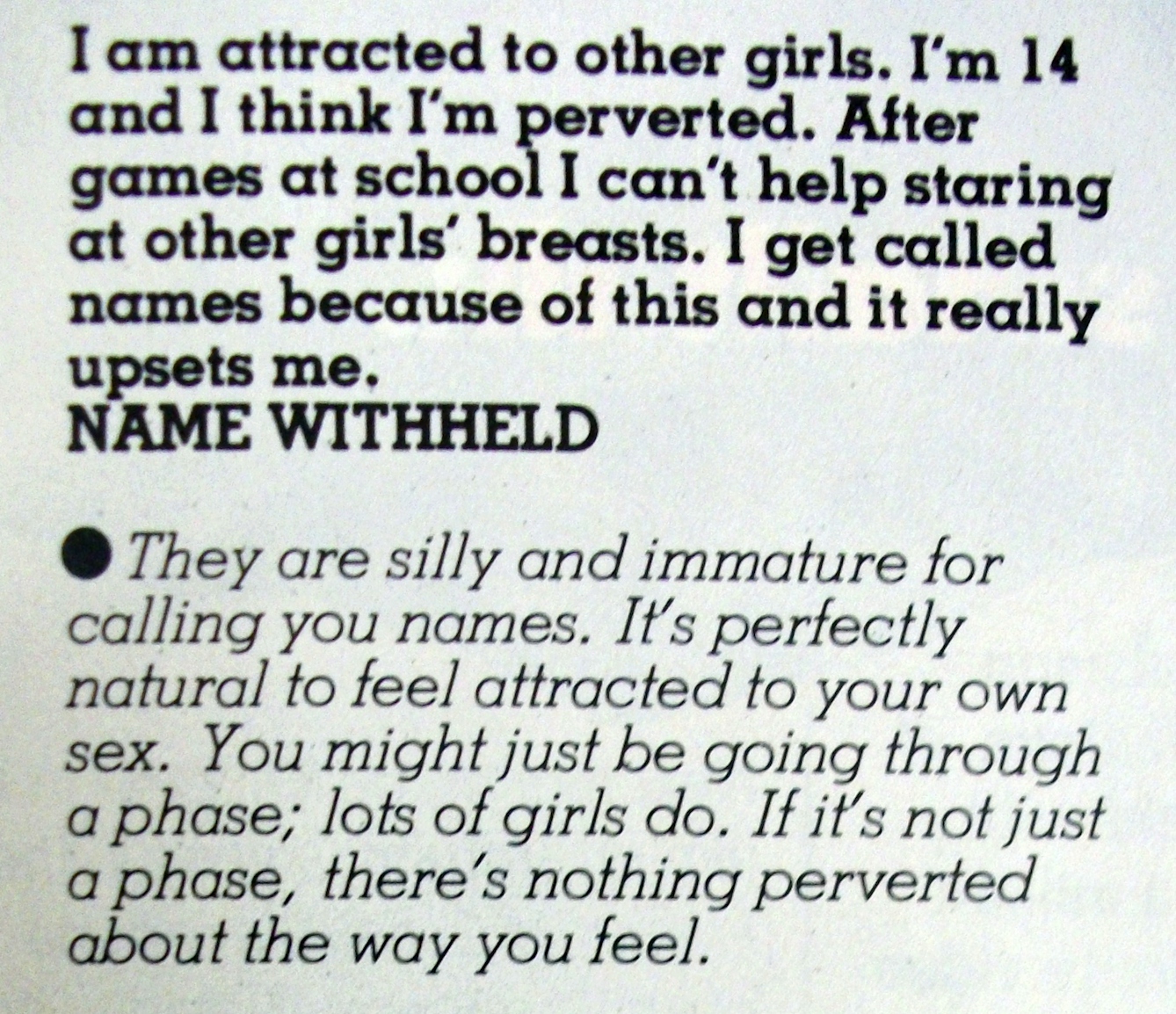

Sometimes, teen magazines suggested that same-sex desire might be a ‘phase’, but defended young people’s right to feel the way that they did.

Tory backbench MP Peter Luff sought to place age limits on teenage magazines because of the information about sex they provided. In this article, he is quoted as saying: "I have learned things from these magazines which even I did not know at my advanced age."

This increased scrutiny did little to change teenage magazines’ approach to discussing sex and sexuality, but it did result in the inclusion of borders around the problem pages stating that sex below the age of 16 was illegal between male and female teenagers. Previously included in most discussions, this fact of British law became a more prominent problem-page mantra, a rule in the rebellious spaces of teenage magazines, which heterosexual adolescents were told explicitly they must not break. The unequal age of consent between homosexual and heterosexual teenagers was also discussed, with the higher age of consent between men – set at 21 after decriminalisation, and 18 from 1994 – frequently presented as discriminatory. The age of consent between women went largely undiscussed, echoing the law, which did not specify consent between women until 2001.

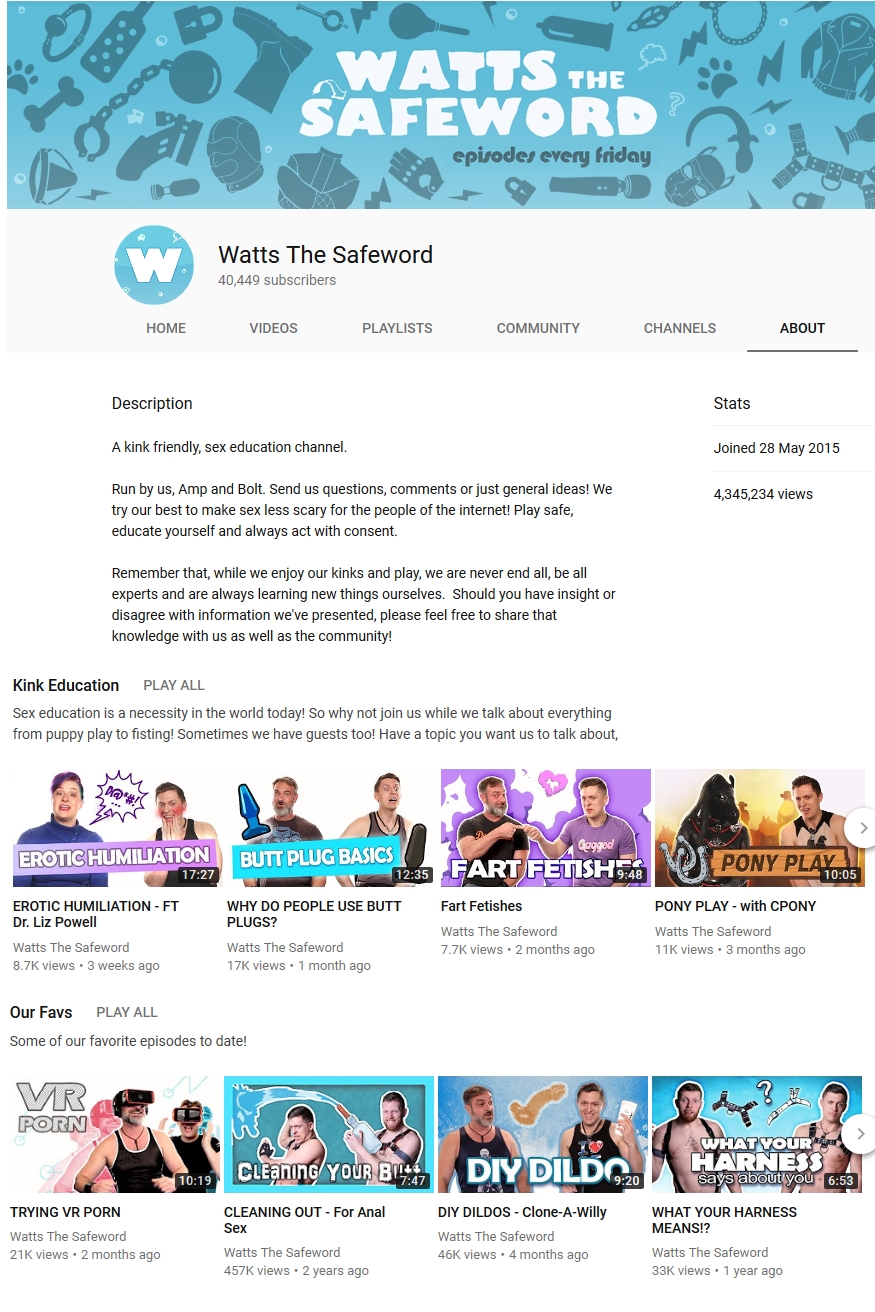

Young people today can turn to YouTube and vloggers for information about sex that is not provided in their schools.

So where do teenagers go now for unofficial sex education? The answer is, unsurprisingly, the internet. Not just by accessing pornography or the bright searchable websites of sex education providers like Brook and the Family Planning Association (FPA) – though undoubtedly these are both sources of information for many teens – but through YouTube. It is to the sex ed vlogger that teens turn when they want a bit more detail or advice on subjects that find little space on school curriculums or more mainstream websites.

Sex ed vloggers, much like the problem pages of teenage magazines in the 1980s and 1990s, provide frank and detailed discussion of topics that remain taboo – menstrual cups, intimate partner violence, abortion – or receive limited space on packed curriculums – consent, queer sexuality – while offering teenagers the opportunity to ask questions and receive answers anonymously, without needing a savvy teacher or parental consent. Like the magazines, though, vlogs may also be subject to attempts to censor their content.

Teenage access to online sex education is far from guaranteed, however; much as reading magazines relied on finances, access to vloggers is contingent on an internet connection that allows the viewing of this sort of content. Both magazines and vlogs can be useful, but they by no means absolve us of our responsibility to ensure that comprehensive sex and relationship education is available in the classroom, too.

About the contributors

Hannah J Elizabeth

Dr Hannah J Elizabeth is a researcher for the Centre for History in Public Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.