Over six years, Ron Hampshire produced a series of works at the art studio in Netherne psychiatric hospital. Do these artworks reflect the improvement in his mental health over that time? That’s a matter of interpretation.

Almost nothing is known about Ron Hampshire, other than that he was a patient at Netherne psychiatric hospital in the 1950s and 1960s, where he attended the art studio set up by Edward Adamson. Ron left behind a series of drawings and paintings, which are now part of the Adamson Collection of artworks by Netherne patients.

The fact that Ron’s work exists at all is because of a remarkable ‘experiment’ begun in the 1940s at Netherne. The Medical Superintendent and Research Director, Dr Eric Cunningham Dax, wanted to find out if art produced by patients might be a useful diagnostic tool for psychiatrists, and whether the process of creating art had any therapeutic value for patients. He recruited artist Edward Adamson to help him in his research.

When Adamson arrived at Netherne in 1946, the prevailing view among psychiatrists was that mental illnesses were essentially biological, and best managed with physical treatments such as insulin coma therapy, electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomy and leucotomy.

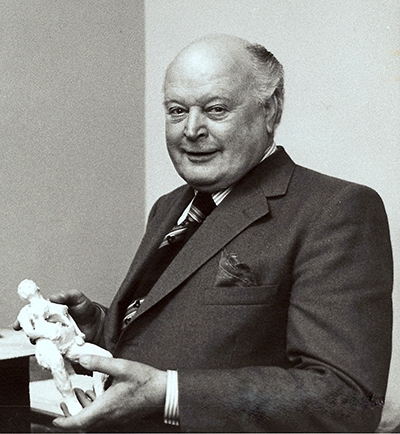

Adamson worked as an artist in the hospital, holding regular open studio sessions in a newly established art studio and passing patient artwork to the psychiatrists to aid their diagnosis. But he was more than a ‘passive facilitator’: he would strike up conversations and lead patients into the creative process by initially drawing the things they talked about.

It was Adamson’s belief that the creative process and the act of making and expressing held the power to heal. So after Dax left in 1951, he used the opportunity to turn the studio into a less clinical creative space, focused more on therapy than diagnosis. The vast majority of the artwork in the Adamson Collection is from this later period (1951–1980s).

The administration building at Netherne Hospital.

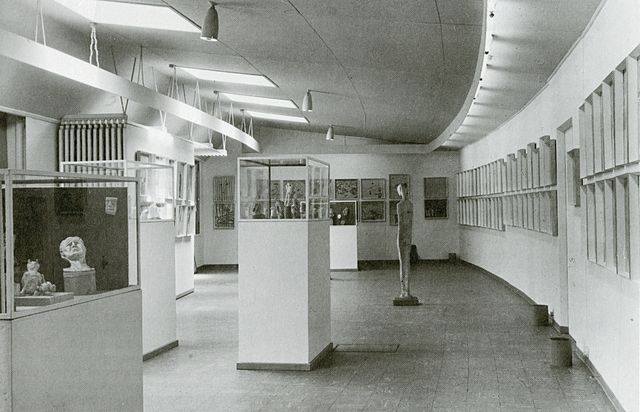

The art gallery of patient works, opened in 1956 by Adamson at Netherne Hospital.

Adamson’s view

Adamson believed in the healing capacity of art, and he believed that a patient’s work could sit simultaneously in the worlds of art and medicine.

His notebooks, written between the 1950s and the 1980s, are filled with unpublished commentary on patient artworks. As well as recording the patients’ insights into their own works, he made his own interpretations.

This is evident in the commentary on a series of Ron Hampshire’s works, which Adamson called ‘Metamorphosis’. According to Adamson, the works demonstrate Hampshire’s clinical progress during his stay at Netherne.

When Hampshire first came to the art studio, he was not speaking and his artwork was confined to marginal pencil sketches. He gradually moved on to sketches across a whole sheet of paper. And sometime later he took up painting, at first simply flooding the paper with colour, and gradually producing more representational images.

In pictures

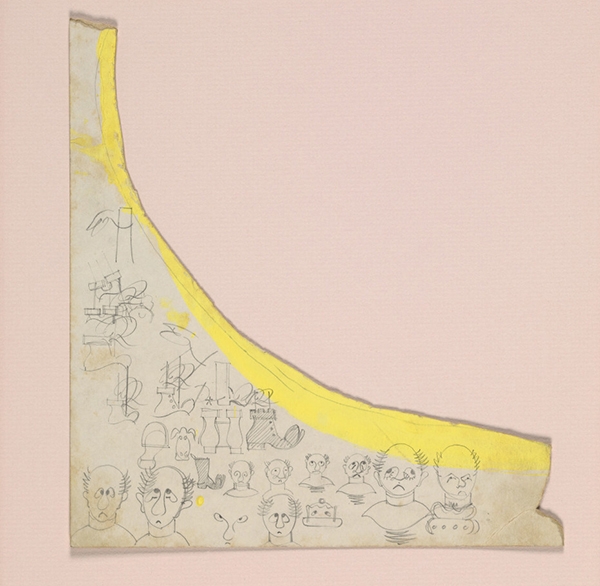

The 'Metamorphosis' series of works begins with a small fragment of card with some sketches and doodles. Adamson provides a commentary on the series in his book 'Art as Healing‘. Before the sketches on the fragment, Adamson says that “previously [Ron] had come for many weeks, and just stared at the blank sheet in front of him”.

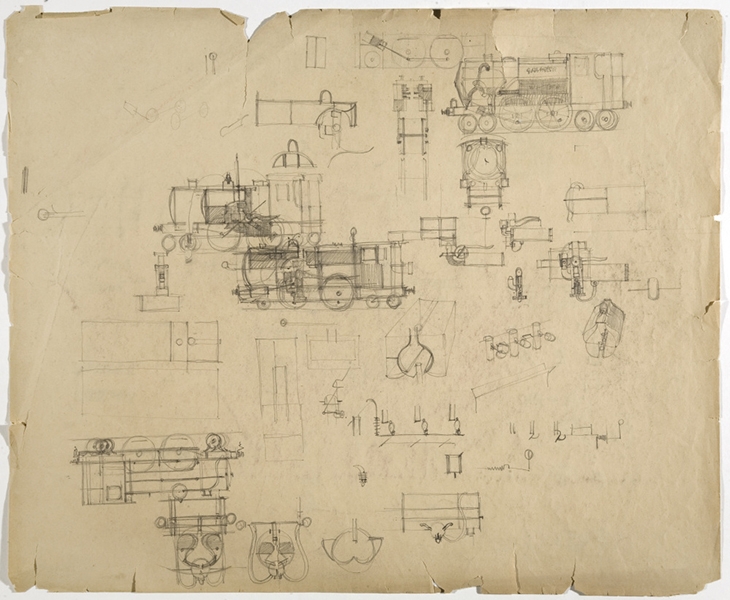

‘Engines’ by Ron Hampshire. Adamson reports that it took another six weeks before Ron “finally summoned the courage to tackle a larger sheet of paper”. The mechanical sketches were done in pencil.

Untitled work by Ron Hampshire. After a further six months Ron took up painting. Adamson describes how Ron “covered the paper with clear water. He subsequently dipped his brush in paint and flooded the colour onto the wet paper, allowing it to form its own pattern.”

'The Lake' by Ron Hampshire. This was Ron's first attempt at a landscape. Adamson sees this as significant. "Here is a sensuous delight in the use of colour, quite in contrast to the rigidity of the first pencil drawings."

'Christmas Decorations' by Ron Hampshire. Adamson explains that Ron was very fond of a shiny red bauble, which he carried around with him. While painting it, a ghost ship emerged in the painting.

‘The Shipwreck’ by Ron Hampshire. The ghost ship has turned into a black galleon in a stormy sea. In Adamson’s interpretation, “A sole survivor can be seen swimming away. His head is just visible above the waves in the lower right of the picture.”

‘The White Ship’ by Ron Hampshire. In a continued commentary on Ron’s progress as seen through his art, Adamson says: “Rescue comes in the form of a ship with sails of white flowers in full bloom. The sea is calmer now and a new dawn breaks on the horizon.”

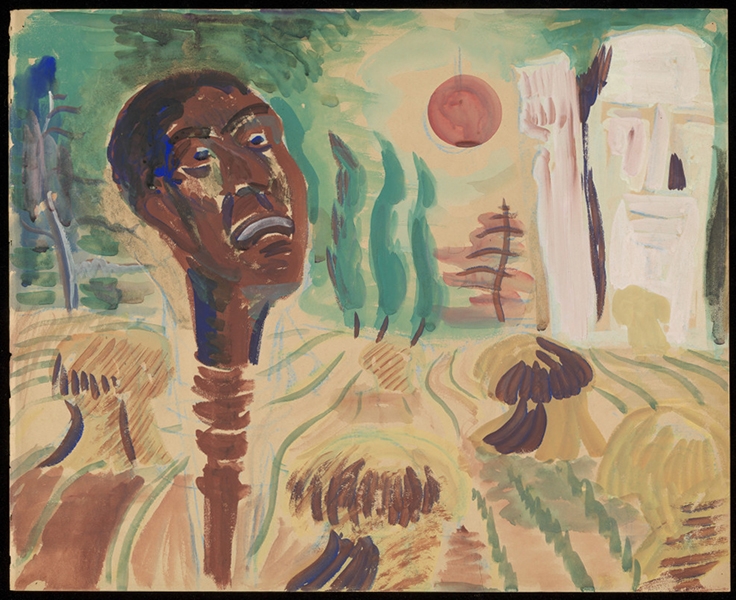

‘The Severed Head’ by Ron Hampshire. Adamson sees signs of a struggle in this work where “the setting is now on dry land in what seems to be a cornfield”. Adamson notes that at the time the picture was painted, Ron “was beginning to use one or two words with great difficulty”.

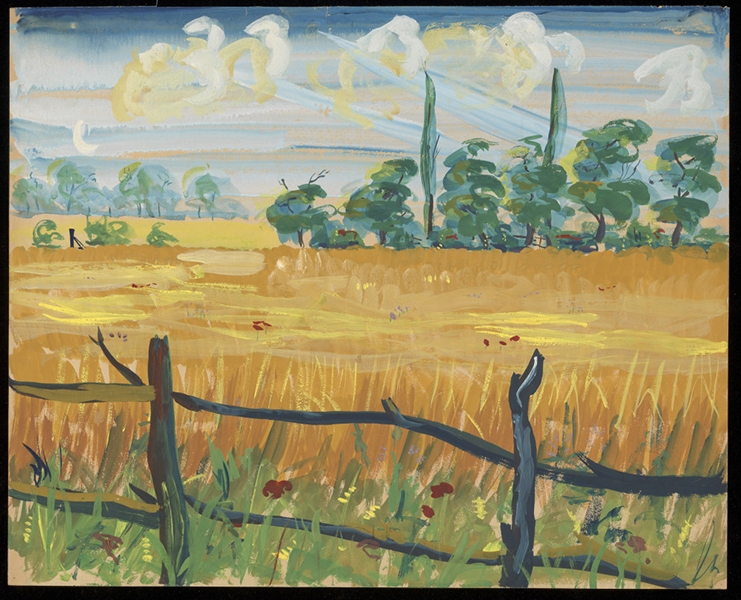

‘The Cornfield’ by Ron Hampshire. The cornfield is now ripe and golden, ready to be harvested. But, Adamson observes, “There is still an ominous dark fence which surrounds the field.”

'The Trees' by Ron Hampshire. When Ron painted this picture he could talk with increasing fluency. For Adamson, "the dark fence has retreated to enclose the house in the background" and the trees are in full bloom in a field of flowers.

Adamson notes that at the same time, Ron slowly began to use one or two words. Adamson called the last painting in the ‘Metamorphosis’ series ‘The Apple Harvest’. In this work, the apple harvest has been gathered and a discarded smock hangs from the tree. Adamson reports that Ron “now spoke without difficulty” and after this final work “he lost all interest in painting” (Adamson, ‘Art as Healing‘, 1984).

The artist/patient view

For Adamson, it was possible to read the improvement in Ron’s mental health in his artistic development. But Matthew, who is Artist-in-Residence with Bethlem Gallery, has a very different interpretation: “I can understand why Adamson and hospital staff might have looked at this work and seen it as representing progress; a transition from darkness and silence to light.”

“It’s tempting to read diagnostic clues in works of art,” he continues. “Most people would think that dark colours are sad and troubling, and light colours are bright and happy, but I actually find bright colours unsettling.”

Matthew thinks that Ron’s earlier paintings (‘The Lake’, ‘Christmas Decorations’ and ‘The Shipwreck’) have “real honesty, real emotion and depth”. But for him “the later paintings seem hollow and meaningless. There’s something false about them.”

Was Ron giving Adamson and the doctors what he thought they needed to see? Matthew thinks so: “For me, this is a perfect example of the hospital experience. You come in, you paint, you learn what you have to do to get discharged and you paint bright, happy pictures of houses and apple trees to get out the door.”

But Adamson was well aware of the risk of influencing students/patients in the studio: “It is not unknown for an astute patient to ‘catch on’, as it were, to what he feels the instructor is looking for and to supply it for an indefinite period,” he observed. For Adamson, the diagnostic and therapeutic value of the artworks was a matter of careful interpretation alongside the personal interactions and the process of creation.

The art therapists’ views

Art therapy’s complex identity is rooted in art, art education, psychoanalysis and psychiatry. Along with other artists such as Adrian Hill, Adamson was instrumental in the founding of art therapy as a profession in Britain.

The use of art therapy has changed since Adamson’s day, when people with schizophrenia and other psychoses were the prime subjects. Val Huet, Chief Executive Officer of the British Association of Art Therapists says today’s art therapist works with children and adults who have experienced emotional distress and may be too ill or traumatised to communicate with words alone.

So what do contemporary art therapists make of Ron Hampshire’s paintings? A group of practising art therapists came to Wellcome Collection to view and discuss works from the Adamson Collection.

Some agreed with Adamson’s assessment that the works were evidence of a progression in Ron’s condition. Donna Goodman thought that “Ron’s artwork can be experienced as his journey through psychosis and hospitalisation” with the turning point “symbolically represented in ‘The Storm’”.

Jill Davies accepted that, “We can never know exactly how Hampshire felt or whether the true nature of his recovery was reflected in the bright, idealised scenes of his later work.” But she did see “the growth from basic mark-making to the ‘flooding’ of emotion, which seems to embody the opening of an emotional dam and corresponds to him regaining his voice”.

Helping people through art is itself as much an art as a science. As psychotherapist Katherine Heritage says, “Holding uncomfortable, vulnerable or incomplete expressions is integral to the work of an art therapist.” We may not know much about Ron Hampshire, but we know that his mental health did improve at Netherne, and in his works, he has left traces of himself as vivid as any photograph.

About the contributors

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the histories of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.

Solomon Szekir-Papasavva

Sol is the Engagement Officer for the Art & Health project at Wellcome Collection. The project involves cataloguing and promoting the use of selected art and archive collections in the Library.