Today we view talent as something within us, but in ancient times every man had his own external genius. Could this be a safer way to foster creativity than lauding the great individual?

Genius spirits and the mystery of creative inspiration

Anna Fahertyaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

In a 2009 TED talk, American writer Elizabeth Gilbert warned that identifying people as geniuses could be bad for their health. The concept of individual, innate talent, said Gilbert, puts pressure on people to perform, creating unmanageable, unachievable expectations.

Effectively, Gilbert advised that instead of trying to become a genius, it’s better to call on your genius and ask them for help. In doing so, she referred to a time when every man had his own genius – a spirit that watched over him.

Fortifying the family

The earliest concept of genius dates back to ancient Italian spirits who were believed to protect the household. The word itself is Latin, deriving from the verb gignere, meaning ‘to generate’ or ‘to father’.

In Roman times, the genius spirit blessed the head of the household and his wife with children.

The genius spirit ensured a family prospered by blessing the head of the household and his wife with children. Its power was evident in the marital bed, and it was represented visually through symbols like the horn of plenty, the phallus, phallus-like serpents or flowers and greenery.

Families celebrated the genius spirit on the anniversary of the man of the house’s birth. This forerunner of the modern birthday party is recorded in verses written by first-century BCE Roman poet Tibullus, who describes his friend’s birthday as a happy occasion. Flowers are brought inside and incense is lit. Wine is offered to the genius spirit along with cakes sweetened with honey. At one point, Tibullus asks his friend to make a wish and calls on the genius to grant it. Finally, Tibullus asks the genius to bless his friends with children.

From life force to personal protector

Ceremonies like this replenished the genius, generating new life and energy for both the spirit and the household. Roman genius was a kind of personal life force, a concept philosophers and psychiatrists revisited centuries later, when they linked genius with a man’s ‘vital force’, a euphemism for sexual energy.

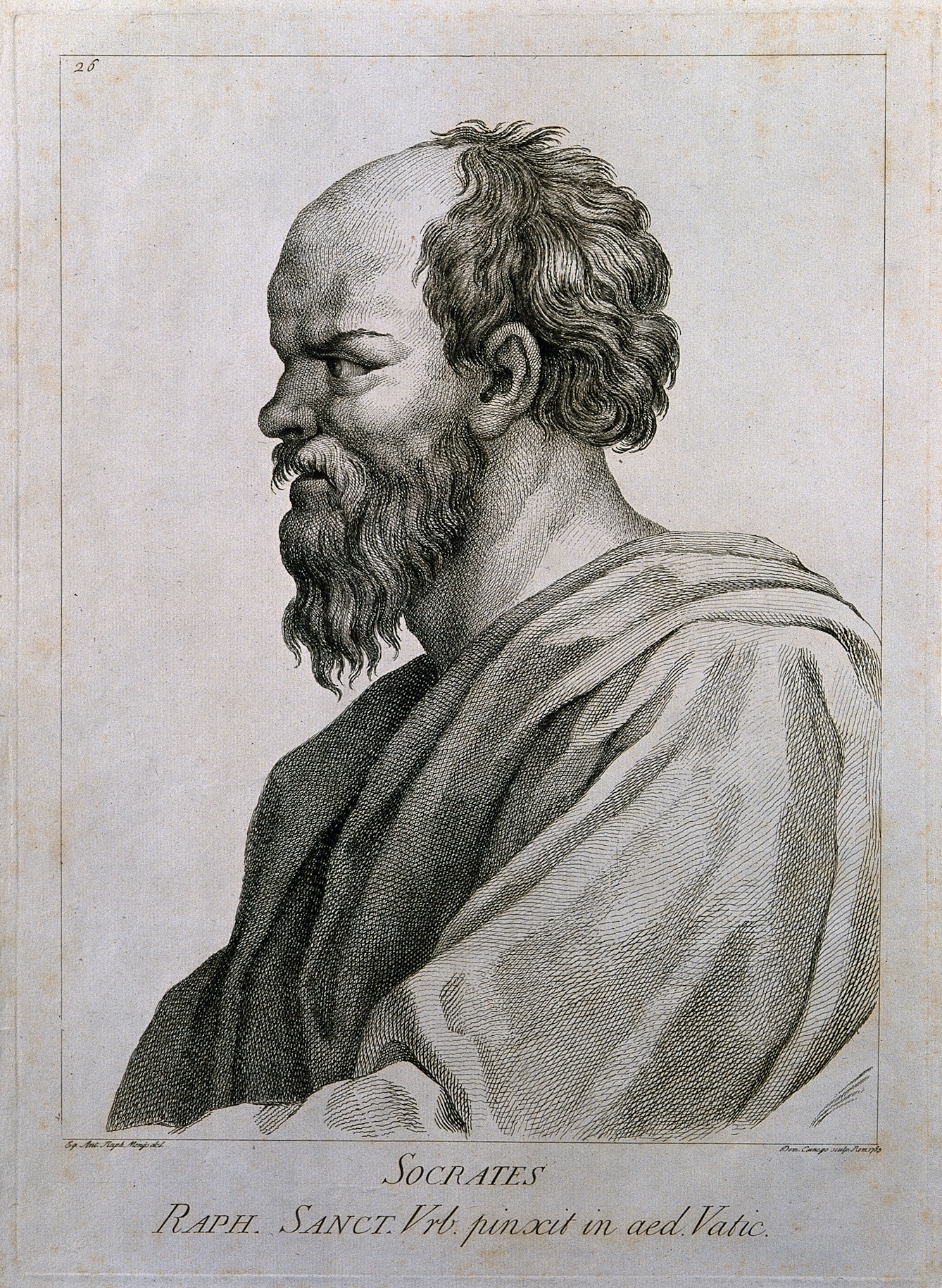

The ancient Greeks took a different view. Their personal spirits, or ‘daemons’, were wise, divine messengers who mediated between the gods and mortals, a little like the angels of Christianity. Greek philosopher Socrates described his own daemon as a voice that advised against certain courses of action.

Socrates said he heard a voice that advised him against certain courses of action.

I am subject to a divine or supernatural experience… It began in my early childhood – a sort of voice which comes to me; and when it comes it always dissuades me from what I am proposing to do.

Following the Roman invasion of the Greek peninsula in the second century BCE, Greek and Roman beliefs began to intermix. Genius eventually became a personal guardian that protected an individual’s life and fortune. Roman poet Horace described it in the first century BCE as “the companion which controls the natal star”.

Each genius was unique, just like the astrologically influenced personality of each man it protected. But if every man had his own genius, what, in a creative or intellectual sense, set some men apart from others?

Greek–Roman writer Plutarch felt Socrates was able to hear and act on the voice he heard because he stayed celibate, sought wisdom and turned his back on material possessions. Other men might have daemons but they were too distracted by passion and desire to heed them – effectively, they expended their ‘vital force’ in other ways.

For Plutarch, if you lived your life well you would be rewarded by the wise voice of the divine. This privilege extended to writers who might today be considered geniuses but who, in their own lifetimes, were simply divinely inspired.

Inspired by the gods

In ancient times, poets like Homer, Virgil and Ovid were thought to have no talent of their own. They received their inspiration – from the Greek inspirare, meaning ‘to breathe into’ – from the only beings who held the power to create anything: the gods.

The Greek philosopher Plato described poets becoming possessed, like soothsayers or prophets. During a state of divine frenzy, their minds were not their own. Today we might think of this as a ‘flash’ or ‘stroke’ of genius. Albert Einstein described it as “a sudden illumination, almost a rapture”, while Elizabeth Gilbert calls creativity a “downright paranormal” experience.

Creation as divine inspiration

The Grace of God inspires the mind.

God inspires life into man.

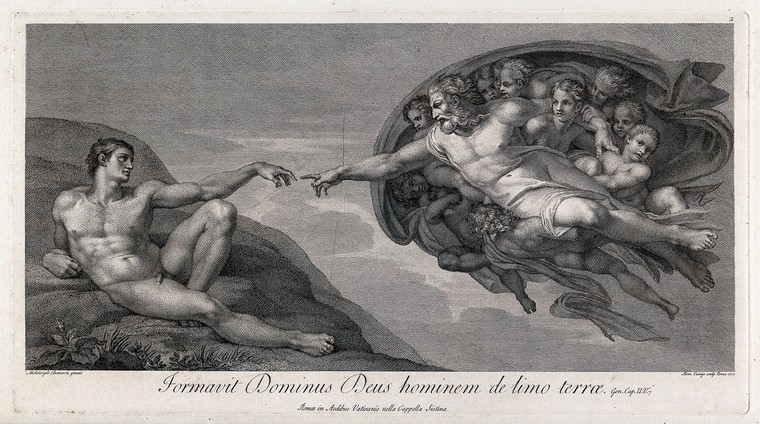

God creates Adam.

An archangel reveals the physical nature of the universe to a group of natural philosophers.

A muse reveals information about the stars to a powerful man.

For centuries, philosophers and poets were the only groups blessed with creative inspiration. But, by the 16th century, Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari attributed his contemporaries’ talents to similar divine interventions.

In ‘The Lives of the Artists’, Vasari praises Leonardo da Vinci’s realistic paintings of nature, which come “from God”. However, Vasari reserves his highest praise for the painter and sculptor Michelangelo Buonarroti, known during his lifetime as Il Divino or ‘the divine one’.

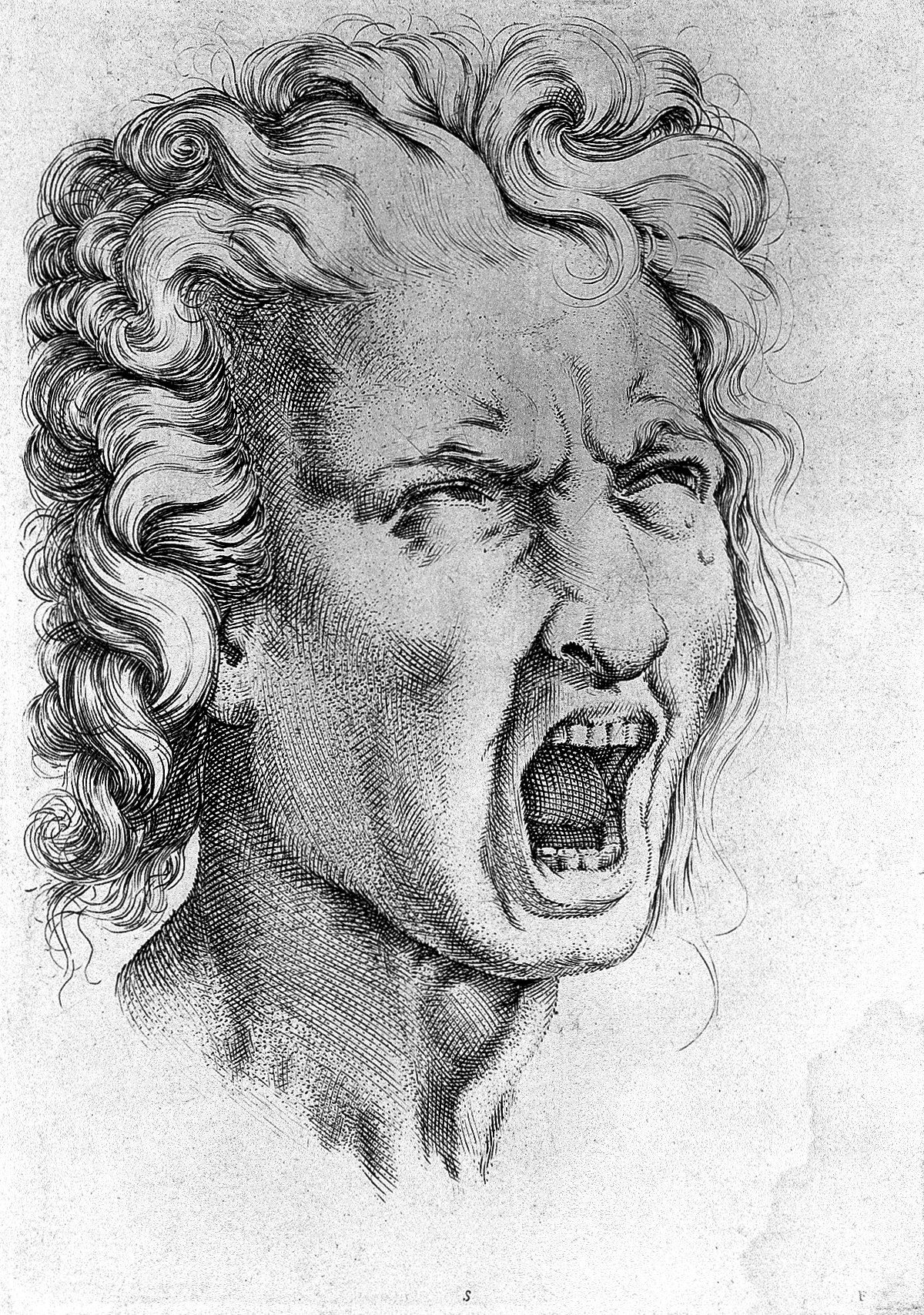

Michelangelo’s ability to portray emotions was thought to be directly inspired by God.

According to Vasari, God sent Michelangelo into the world to demonstrate perfection in design, sculpture and architecture. Michelangelo’s skills in revealing the thoughts and emotions of his subjects were, wrote Vasari, “directly inspired by God”.

The great individual

Attributing genius to the work of spirits or divine inspiration was the norm until the mid-1700s. From then on, exceptional people were considered geniuses in their own right.

As belief in angels, saints and prophets waned, great men (they usually were men) took on the mystery, awe and wonder once held by religious beings. Elevated to the status of gods and saints, geniuses became objects of worship.

For the first time, mere mortals with highly active imaginations had access to the mysteries of the universe or our inner selves. These human geniuses also had the power to create things without divine intervention.

It was at this point that people looked back and identified writers, artists and thinkers of the past as geniuses, from mathematician Isaac Newton and artist Leonardo da Vinci to playwright William Shakespeare and the poet Homer.

The faculty of imagination depicted as an artist.

While artists became heroic figures during the 18th century, art itself changed. The pinnacle of artistic achievement was no longer the perfect reproduction of nature. Inspiration, previously the literal breathing of ideas into a person, now came from within, and imagination and individuality became all important.

Diligence and acquired abilities may assist or improve genius; but a fine imagination alone can produce it.

Placing all the power of genius within the individual was, believes Elizabeth Gilbert, “a huge error”. Artists navigating the “maddening” and capricious creative process no longer have anyone else to credit – or blame – for their success or failure.

For their own sanity, Gilbert, who admits she may never repeat the success of her first book, wants artists to construct a buffer between the individual and their craft. By attributing success or failure to something outside their own talent, artists could release themselves from the unbearable pressure to draw from their own internal imagination. In ancient times, such a buffer involved experiences that might today be viewed as delusions or afflictions. It’s no wonder then that genius and madness have long been linked.

About the contributors

Anna Faherty

Anna Faherty is a writer and lecturer who collaborates with museums on an eclectic range of exhibition, digital and print projects. She is the author of the ‘Reading Room Companion’ and the editor of ‘States of Mind’, both published by Wellcome Collection.