In the 19th century, genius was closely linked with tuberculosis. The debilitating disease was thought to fuel writers like Robert Louis Stevenson, even as it consumed them.

Tragic artists and their all-consuming passions

Anna Fahertyaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

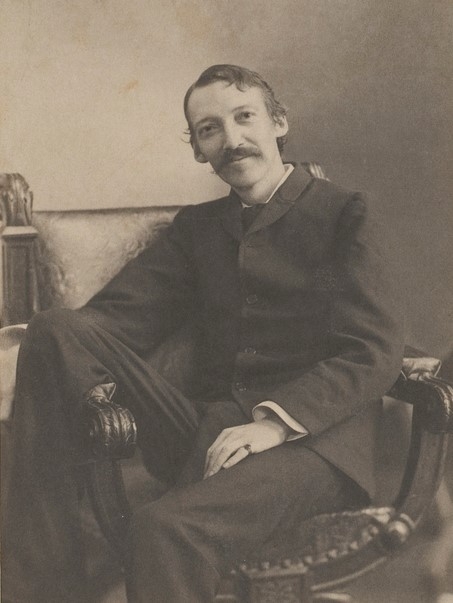

In 1880, Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson fell seriously ill while staying in California. When he began to spit blood, it was a sure sign he had consumption, so-called because it appeared to eat away patients’ withering bodies.

Robert Louis Stevenson photographed around 1893.

Today we know the condition as tuberculosis, or ‘TB’, an infectious bacterial disease that often targets the lungs, which gradually deteriorate. Stevenson called his illness “Bluidy Jack”.

Seven years earlier the writer had been sent to the south of France to boost his failing health. At the age of 23, he weighed just 53kg, well under what we’d consider healthy for a man of his height (178cm) today. In California, a fisherman described Stevenson as the thinnest man he had ever seen. Years later, he was likened to a bundle of sticks in a bag.

Stevenson harboured a persistent cough, was prone to fevers and spent long periods of his life confined to bed. Yet he produced some of the most vivid examples of English literature, including the adventure story ‘Treasure Island’ and the novella ‘Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’.

High spirits

Stevenson wasn’t alone in producing great and lasting work despite suffering from a chronic wasting disease. English writer Emily Brontë, who died of tuberculosis aged 30, was said to grow stronger mentally as she declined physically. And when English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s health declined in 1817, he claimed to possess “unnatural and keen excitement”. Both appeared to experience what Scottish physician Andrew Duncan observed in consumption patients two years later: a “peculiar flow of spirits, and uncommon quickness of genius”.

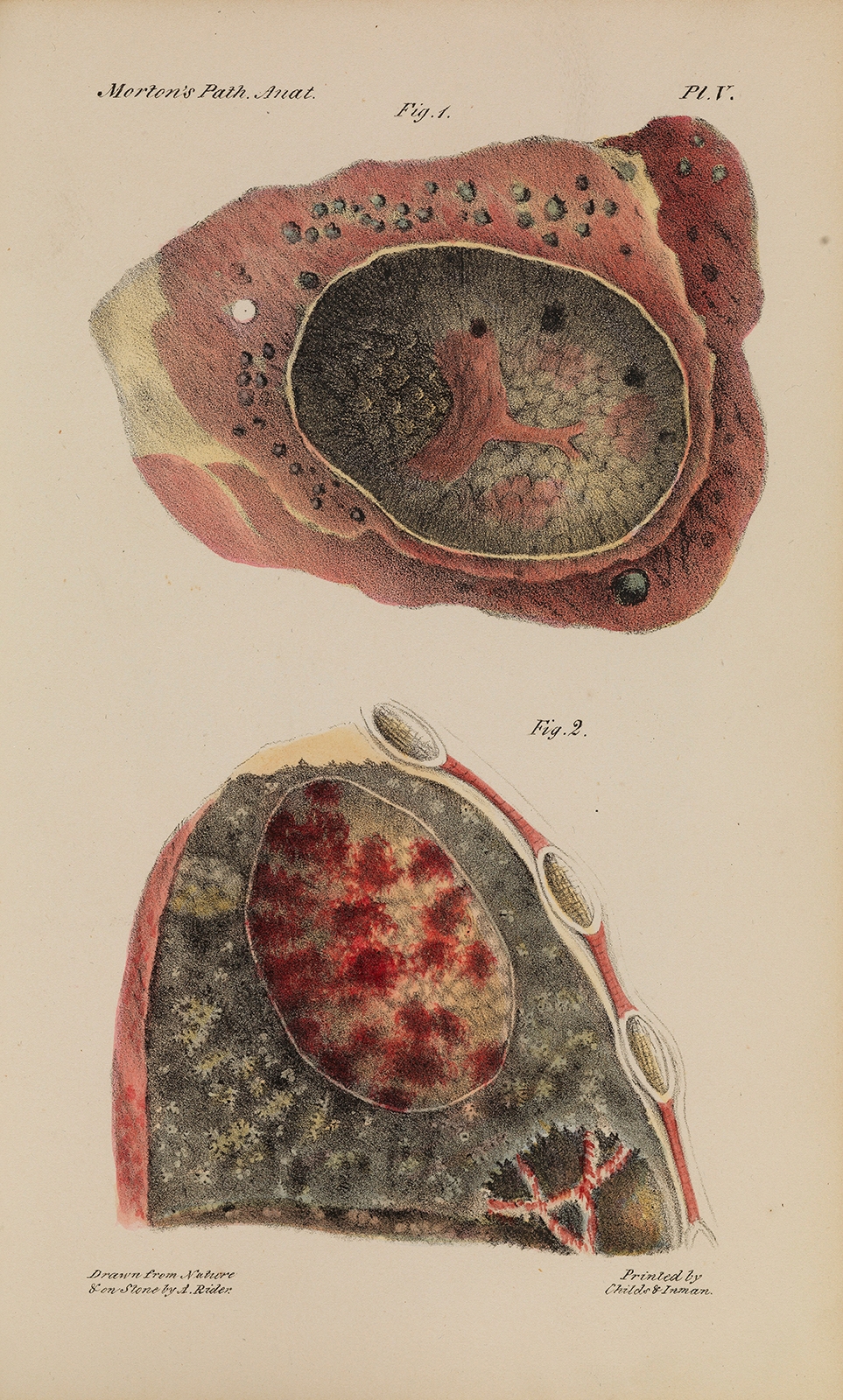

The lungs of a young man who died of TB.

Centuries before, the Greeks named this state of high spirits spes phthisica. First-century physician Aretaeus advised that patients with bleeding in the lungs felt little pain. Despite being seriously ill, they might believe recovery was possible, leading to feverish urges to accomplish things.

Spes phthisica, then, is a state that drives creative production. It is the state American professor Jeanette Marks specifically credited for the power and passion exhibited in Emily Brontë’s novel ‘Wuthering Heights’.

It has been said that a man is what his microbes make him, and in nothing, it would seem, is this more true than with the man of genius.

Other theories suggested patients’ feverishly high temperatures could generate creative energy, as might toxins released by the disease. At the other extreme, some people believed enforced leisure time, and patients’ separation from society, provided uninterrupted opportunities for introspection and idea generation.

This may have been the case with Stevenson, whose poem ‘The Land of Counterpane’ depicts a bed-bound child imagining the objects around him coming to life. The writer was so delicate as a boy that he was often kept home from school. At night, his childhood sleep was interrupted by fever and vivid dreams.

A desirable state

Whatever the mechanism that supposedly linked consumption and creative genius, 19th-century literary and artistic types positively desired to contract the disease. French writer Alexandre Dumas wrote of the 1820s: “It was the fashion to suffer from the lungs; everybody was consumptive, poets especially; it was good form to spit blood after each emotion that was at all sensational, and to die before reaching the age of thirty.”

Many writers, composers and artists conformed to Dumas’s tragic plot. English poet John Keats died of consumption aged just 25, as did Russian painter Marie Bashkirtseff, who chronicled the progression of her disease in a bestselling published diary.

I cough continually! But…, far from making me look ugly, this gives me an air of languor that is very becoming.

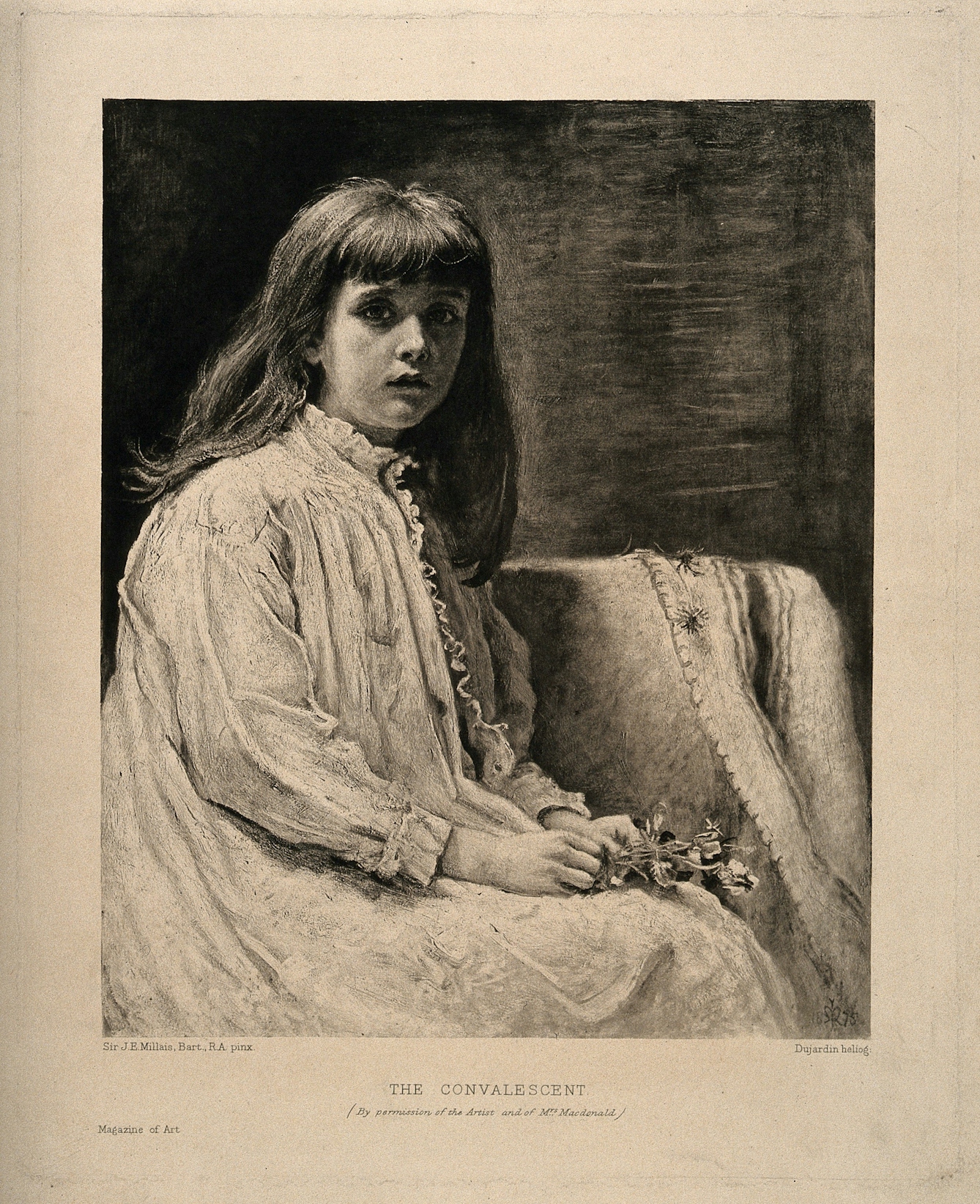

Great artists were, it was thought, more susceptible to illness than ordinary people, since they alone prioritised their minds and creative abilities over their bodies. The pale, emaciated look of ‘a consumptive’ became highly fashionable. Invalids were “interesting”, as English poet Lord Byron said after announcing he “should like to die of consumption”.

The pale and interesting invalid

Elizabeth Siddal was known for her fragile appearance as much as for her writing or art.

A recovering girl in a nightdress features in ‘The Convalescent’.

A sickly girl reclines on a chaise lounge while being attended to by three other women.

A pet dog looks enquiringly at a wan girl in this painting, entitled ‘Are You Better?’

A young woman convalesces in a country garden, beside a pretty cottage.

In the 1880s Stevenson found himself cast in this glamorous invalid role. Frail in body yet producing prolifically, he was widely considered a genius, destined to die young like a Romantic poet.

The story Stevenson’s stepson later published about the ‘Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ supports this image. Stevenson supposedly wrote the novella over three days, working non-stop in bed. After tossing the manuscript on the fire – because his wife criticised it – he then spent the next three days in “feverish industry…, writing, writing, writing” a new draft.

Constrained consumptives

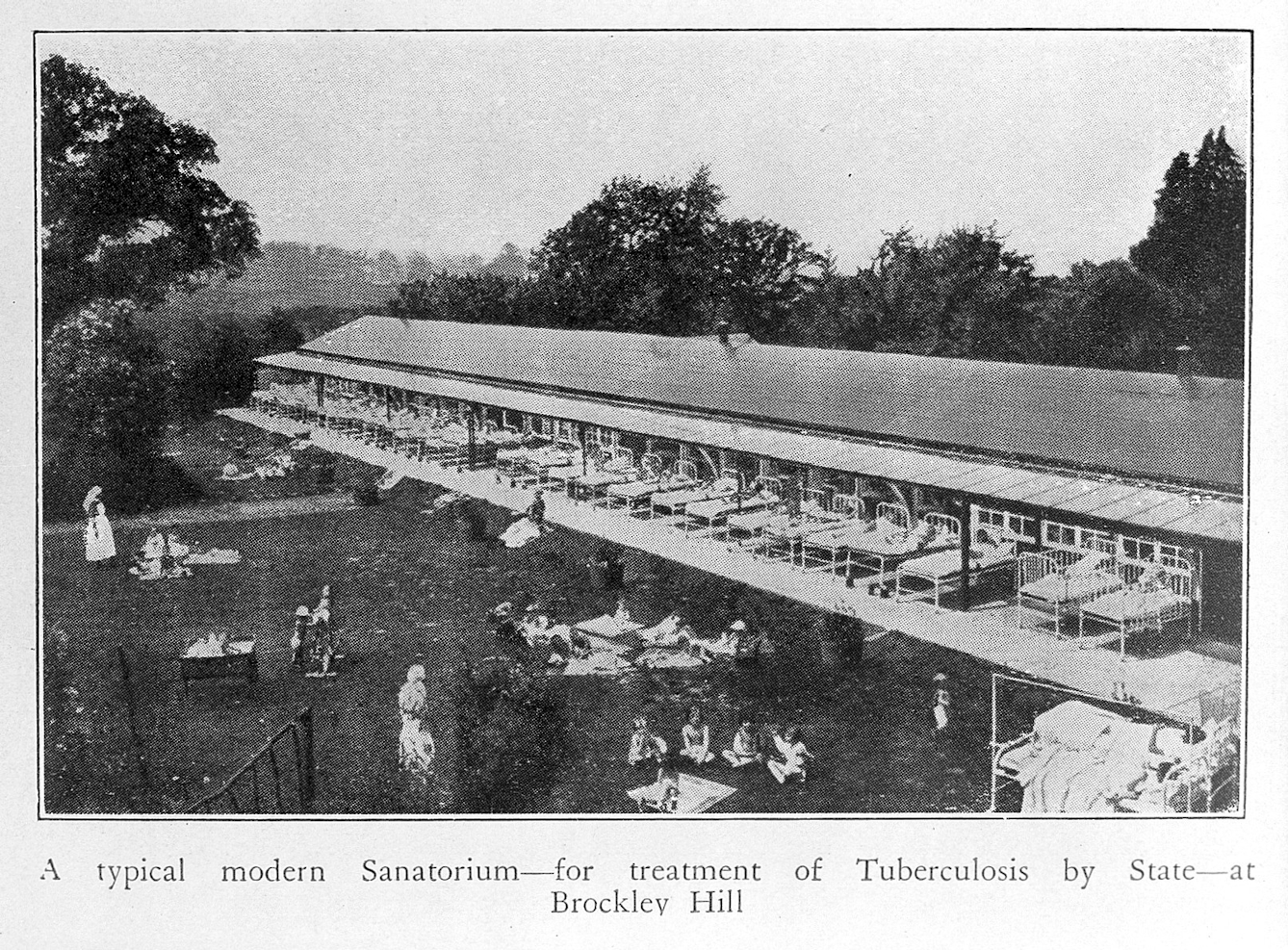

Such Romantic tales were at odds with the constraints of medical treatment. Consumptives were despatched to sanatoriums or other locations in warm climates and expected to take rest, air and sun at prescribed times. Overstimulating activities like writing and painting were out of the question.

Beds lined up outside the Brockley Hill Sanatorium for Tuberculosis.

During a spell in the French Riviera town of Hyères, Stevenson was not permitted to speak. Kept in a dark room with his right arm bound against his body, there was no way he could write. Aged just 33, he was told to consider himself an old man and to conduct himself accordingly.

The only true respite available to consumptives came from medicinal drugs, including opium and cocaine. These substances undoubtedly affected some patients’ creative output. Stevenson used both, as well as morphine. Though we don’t know the exact cause of his inspiration, Stevenson wrote the ‘Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ while staying on England’s south coast, at a time when he regularly experienced terrifying morphine-induced nightmares.

Enveloped in fog

In retrospect, the number of 19th- and early 20th-century artists and writers who suffered from TB is unsurprising. The disease was rife at all levels of European and American society, with up to one in four of the population dying from it.

Consumption may have been alluring to some, but the consequences were dire and deadly.

Any serious study of the link between genius and TB is, however, hampered by the fact that we now know many of those considered consumptive, including Robert Louis Stevenson, may have suffered from other lung diseases.

Whatever the underlying cause, the reality for Stevenson was that bouts of poor health forced him to stop working. Reduced to twiddling his fingers, he lamented “the profound ennui and irritation of the shelved artist”. Likewise, Marie Bashkirtseff wrote in her diary that she was “indifferent to everything” while confined to bed. On one such occasion, Bashkirtseff recounted, her artistic mentor compared her to an autumn landscape: desolate, deserted and enveloped in fog.

Unsurprisingly, when New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield began to cough up blood in 1918, she immediately feared she wouldn’t be able to write: “How unbearable it would be to die – leave ‘scraps’, ‘bits’… nothing real finished.”

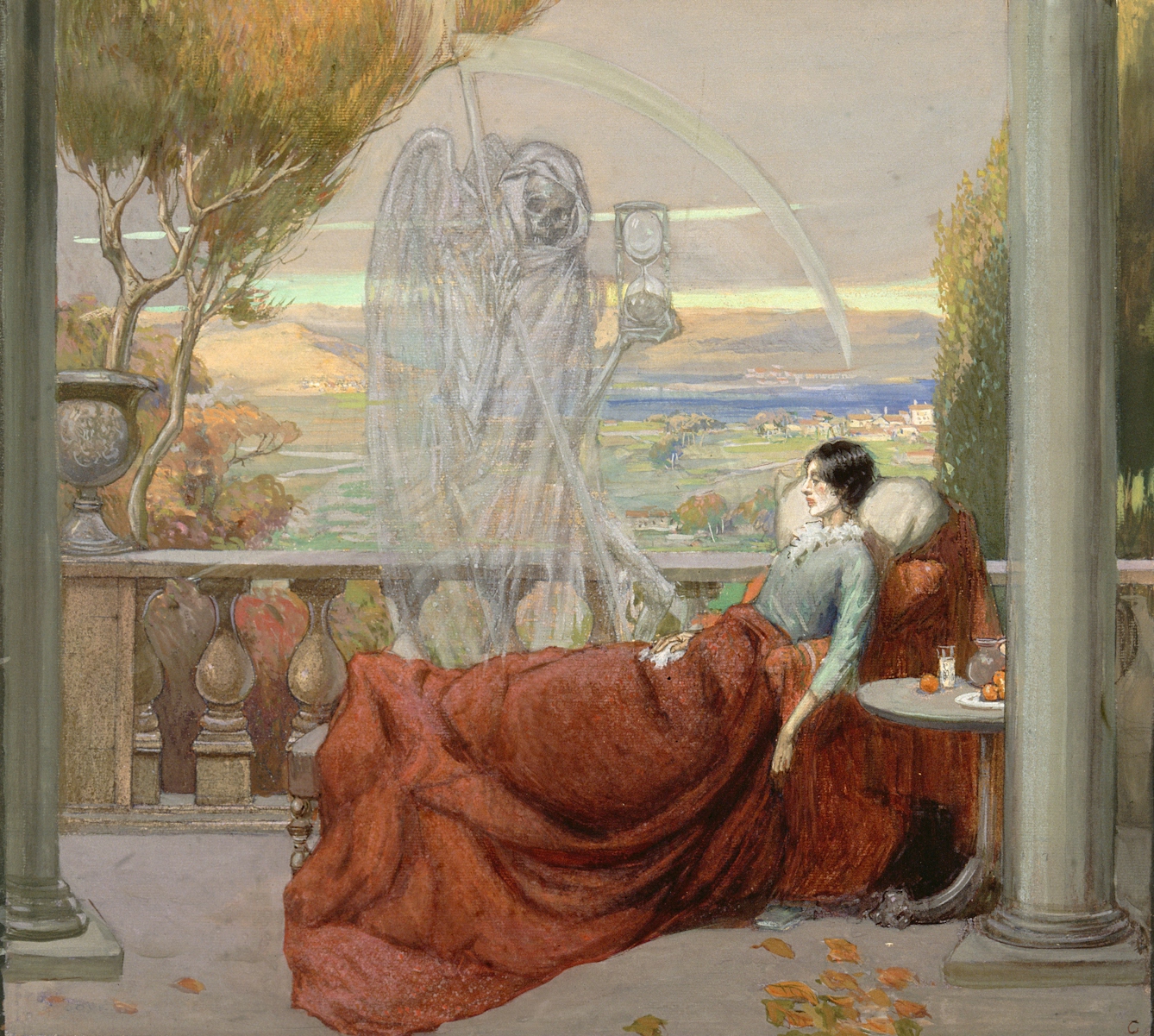

Perhaps it was simply visions of mortality, then, that prompted consumptives’ frantic bursts of creative activity during intermittent periods of respite and clarity. Whether or not consumption caused or enhanced genius, the disease had an undeniable allure for some.

About the contributors

Anna Faherty

Anna Faherty is a writer and lecturer who collaborates with museums on an eclectic range of exhibition, digital and print projects. She is the author of the ‘Reading Room Companion’ and the editor of ‘States of Mind’, both published by Wellcome Collection.