At the turn of the 20th century, medical experts and the public alike thought great writers and artists must surely be touched by madness. To test this theory, French writer Emile Zola embarked on a major psychological project.

The enduring myth of the mad genius

Anna Fahertyaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

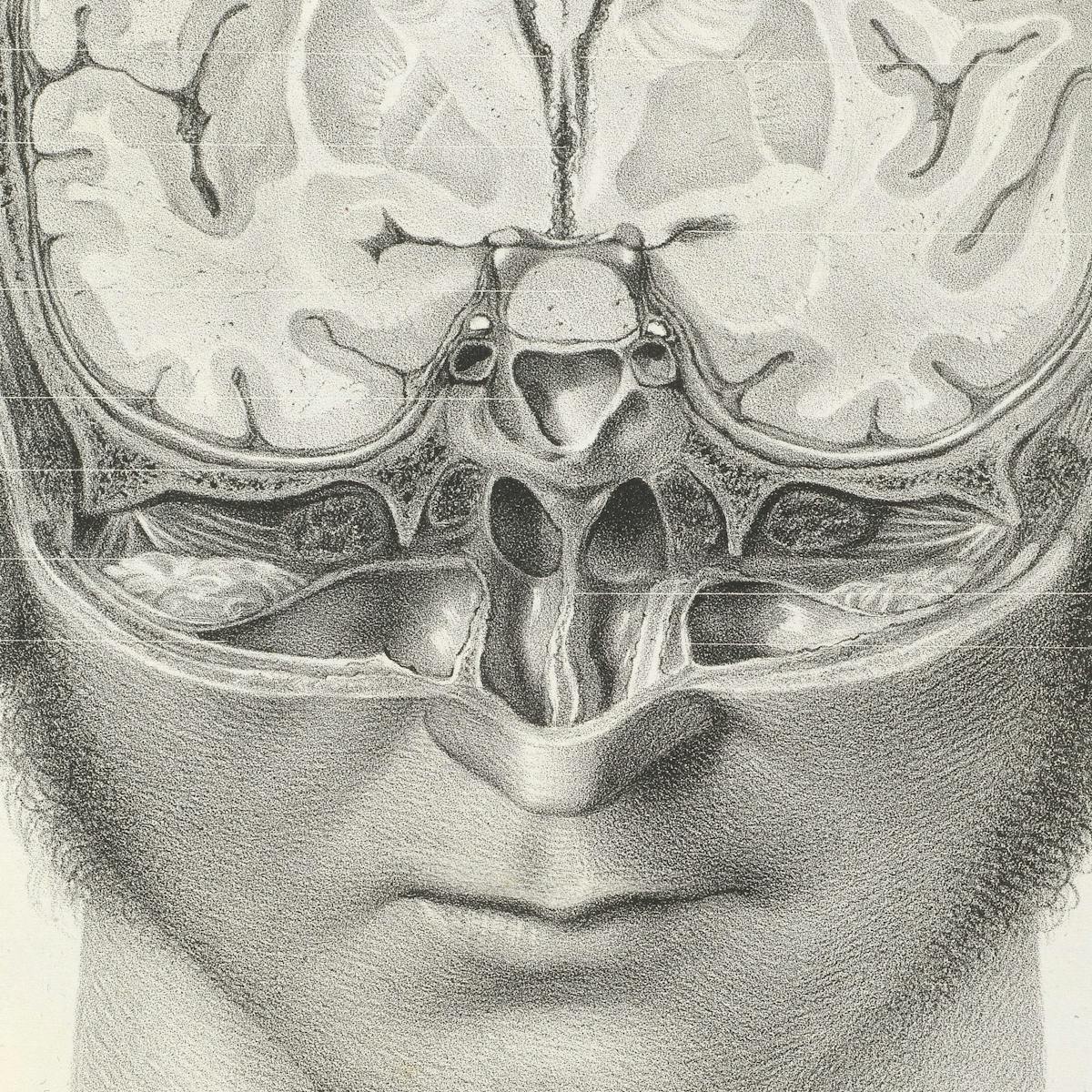

In 1896, Emile Zola donated his brain to science. This was no posthumous bequest, destined for dissection by medical students. Zola was very much alive at the time. The novelist laid open his “glass cranium”, he said, so the physical and psychological nature of a writer could be investigated.

For almost a year Zola was scrutinised by young French psychiatrist Édouard Toulouse and a team of crack medical men. Toulouse applied methods usually forced on asylum patients to a man he considered intellectually above the norm.

The study explored Zola’s medical history, vital signs, memory and vocabulary. One expert debated the likely source of Zola’s facial wrinkles, while another collected the writer’s attitudes towards women. Zola’s work habits were assessed, as was the organisation of his workspace. Some investigators used the relatively new technology of photography to capture and communicate information about the writer.

Examining Emile Zola

Among other things, the psychological study used photography to record Zola’s physical appearance and vital signs.

Studying Zola’s hands.

Studying Zola’s hands.

Studying Zola’s hands.

Studying Zola’s hands.

Zola was, Toulouse concluded, “a neuropath” with an unbalanced nervous system. According to medical thinking at the time, if the nerves carrying sensations around the body became too taut or too relaxed, mental or physical illness might result. Poets, artists, musicians and other creative people were thought to have particularly elevated nervous sensibilities – to be ‘highly strung’, if you will – a state that could lead to mental imbalance or instability.

Beyond the norm

The idea that great writers, artists and composers share a tendency towards insanity was at its height when Zola submitted himself to Toulouse’s examination. As artists gained freedom to be more organic, spontaneous and imaginative than in the past, they were perceived, like the insane, as something other than ‘normal’.

MAD – affected with a high degree of intellectual independence; not conforming to standards of thought, speech and action… at odds with the majority; in short, unusual.

This painting by Louis Wain shows a cat on its hind legs. Wain’s depictions of cats became increasingly abstract after he was certified insane.

In 1838, French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Esquirol highlighted “great analogies” between creative people with active imaginations and the insane. Two decades earlier, German physician Anton Dietrich attributed the disturbed mental state of Russian poet Konstantin Batiushkov to the “limitless dominance” of the writer’s imagination over other aspects of his mind. This, said Dietrich, suppressed the poet’s judgement and enabled absurd thoughts to go unchecked.

For some, such disturbances could open up new creative directions. For example, English artist Louis Wain’s well-known depictions of cats appeared to transform into increasingly abstract patterns as his illness progressed. Mental ill health might also provide, as English writer Virginia Woolf once wrote, what was previously dispensed by the gods: inspiration.

Madness is terrific I can assure you, and not to be sniffed at; and in its lava I still find most of the things I write about.

A missing link

Despite any number of anecdotal examples like this, repeated studies since Zola’s time have failed to generate compelling evidence of a significant link between creativity and madness.

Eight years after Zola’s contribution to the scientific study of superior intellect, British physician Henry Havelock Ellis published the results of his own research into about 1,000 creative geniuses. Only 4 per cent exhibited any form of mental illness. A century later, at the end of a 25-year study, American psychiatrist Albert Rothenberg concluded that there is no specific personality type associated with outstanding creativity.

License to create

If there is no link between madness and creative genius, why does the idea remain so pervasive?

One reason is that writers and artists of the Romantic era into which Emile Zola was born valued imagination more highly than reason and judgement. Mental instability, therefore, could be a badge of honour.

The Romantics valued imagination more highly than reason and judgement, and mental instability was sometimes seen as a badge of honour.

Rather than railing against a diagnosis that described him as unbalanced, Zola welcomed Toulouse’s conclusion. In a letter introducing the published results of the investigation, Zola thanked the psychiatrist for debunking his popular image as a coarse, money-hungry labourer. By positioning the writer alongside sensitive intellectuals and creative geniuses, Toulouse had endorsed Zola’s self-perception as an artist “trembling and suffering at the slightest breath of air”, who embarked daily on a fresh battle against his own inner doubts.

In the 20th century, New Zealand writer Janet Frame embraced the association her own diagnosis of schizophrenia opened up with geniuses like artist Vincent van Gogh. Frame adopted what she termed “schizophrenic fancy dress”, speaking and behaving in ways associated with the condition. Even when her diagnosis was thrown out, she initially clung to it, feeling that “the ‘privilege’ of having schizophrenia” brought her closer to great artists than her work did.

In a similar vein, 19th-century essayist Charles Lamb felt that ordinary people could only reconcile the extraordinary works produced by geniuses if they viewed their creators as mad. In this context madness replaces earlier beliefs that creativity was driven by possession and divine inspiration. But, rather than placing geniuses in a privileged position, it stigmatised them.

American psychologist Judith Schlesinger suggests this delivers a feelgood message for ordinary people. If you can never reach the heady heights of a creative genius, at least you can reassure yourself you won’t have to face their mental challenges.

The wrong sort of work

In Zola’s time, madness was often interpreted as a side effect of intense thought. Zola’s own neuropathic condition, according to Toulouse, was worsened by “constant intellectual work”. “He does not stop” wrote Toulouse, an unsurprising trait given the Latin phrase above Zola’s mantelpiece: nulla dies sine linea or ‘no day without a sentence’.

Nothing affects the nerves so much as intense thought… a delirium, melancholy, and even madness, are often the effect of close application to study.

An alchemist concentrates on a book in his study, while Death tells him “My dear Herr Collaborator, you are too hardworking”.

More recently, psychiatrist Albert Rothenberg has highlighted that the specific type of work undertaken by writers and artists can sometimes generate intellectual and emotional strain. Thinking creatively, says Rothenberg, involves thought processes that transcend ordinary logic and the coexistence of opposing perspectives in the mind.

These activities can cause anxiety in some creative people, who then develop unusual or eccentric behaviour as coping mechanisms – the sort of quirks we might expect to observe in a stereotypically ‘mad genius’. But there is a clear, if thin, line between creative thought processes and psychosis. Geniuses tread close to insanity, or behave in ways that make them appear insane, but they preserve their reason.

Zola himself exhibited obsessive habits, like counting doors in the street or objects on his desk. Yet Toulouse felt neither these, Zola’s unbalanced nervous system, nor his trouble feeling emotions harmed the writer’s intellectual abilities. He was not, in Toulouse’s opinion, insane.

About the contributors

Anna Faherty

Anna Faherty is a writer and lecturer who collaborates with museums on an eclectic range of exhibition, digital and print projects. She is the author of the ‘Reading Room Companion’ and the editor of ‘States of Mind’, both published by Wellcome Collection.