A healthy-seeming cook gained unwelcome notoriety as Typhoid Mary, unwittingly spreading disease to co-workers and employers. Ultimately, the New York authorities took extreme measures to protect the public.

The cook who became a pariah

Words by Anna Fahertyaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

New York, 1907. Mary Mallon spreads infection, unaware that her name will one day become synonymous with typhoid.

In March that year, Mallon, a cook, was visited by a sanitary engineer at her place of work, a swanky townhouse on New York’s Park Avenue. The unexpected caller told Mallon he suspected her of making people sick and requested samples of her urine, faeces and blood. This encounter marked the first time any healthy person in America had been accused of transmitting typhoid fever, a disease responsible for the deaths of 13,000 people in the USA the year before.

A typhoid patient, 1882.

Mallon almost certainly thought the engineer’s claim preposterous. It was true that two members of the Park Avenue household in whose kitchen she worked had recently contracted typhoid: a chambermaid, followed, fatally, by the daughter of the homeowner. But Department of Health officials had already blamed the outbreak on the public water supply, and Mallon, who took pride in her work, was surely too clean to be a threat?

Besides, typhoid was everywhere, and Mallon had never had the disease herself, so how could she possibly spread it? Angry at the intrusion into her workplace and the smear against her character, Mallon seized a carving fork and chased her accuser out onto the street.

Mallon’s reaction was the complete opposite of what the sanitary engineer, George Soper, had expected. He later made sense of the cook’s “indignant” and “stubborn” behaviour by classifying her as peculiar and “perverse”, adding descriptions of her walking and thinking “more like a man than a woman” to his otherwise scientific reports. This idea of Mallon as unfeminine, deviant and wayward perhaps made it easier to justify her later treatment, or perhaps even influenced how Soper and others approached her in the first place.

Though the two had not met prior to their Park Avenue showdown, Mallon was identified by Soper as the guilty party in a mystery he had been unravelling for months. Asked to investigate an unexplained typhoid epidemic at the summer house of a New York banker the year before, Soper’s killer clue was the discovery that a cook had started work in the house three weeks before the outbreak and had moved on three weeks afterwards. Soper tracked down this “Irish woman about 40 years of age, tall, heavy, single” and in “perfect health”, through the employment bureau that had placed her in that role.

The next time the pair saw one another, Mallon came home to find Soper waiting for her on the stairs outside her lodgings. She again refused to provide the samples Soper demanded. He responded by recommending that she be taken into custody by the New York City Department of Health. To support his case, Soper shared information about other typhoid outbreaks, dating back seven years, which had all occurred in homes where Mallon had worked. He added that her excrement should be “made the subject of careful bacteriological examination”.

Less than a week later, Mallon turned away another visitor requesting samples of her bodily fluids. The following day this new pursuer, Dr Josephine Baker, returned with reinforcements. Three policemen surrounded the Park Avenue house. Another joined Baker on the doorstep and a horse-drawn ambulance parked nearby, ready to take Mallon away. The as-yet-unproven “germ producer” promptly vanished, taking refuge in the outside toilet of a neighbouring house, while someone else piled a dozen ashcans outside its door.

Several hours later the toilet door was finally pried open and Mallon, fighting and cursing, was forced into the ambulance. On the way to hospital Mallon was said to be so “maniacal” that Baker had to sit on her. When they arrived, Mallon’s faeces were collected and analysed. The results confirmed what Soper’s epidemiological investigations had predicted: Mallon was carrying “a pure culture of typhoid”. Though no one quite understood how this could be the case, given Mary’s good health, it’s likely that she had experienced a mild bout of the disease some years earlier without even noticing.

In 1907 the concept of healthy typhoid carriers was just beginning to generate scientific interest. A year before, a woman who had recovered from typhoid ten years previously had been identified as a carrier in Strasbourg, Germany. Scientists soon realised that the bacteria responsible for typhoid survived in a small percentage of people’s bodies long after any ill effects had passed. Why this happened, no one really knew.

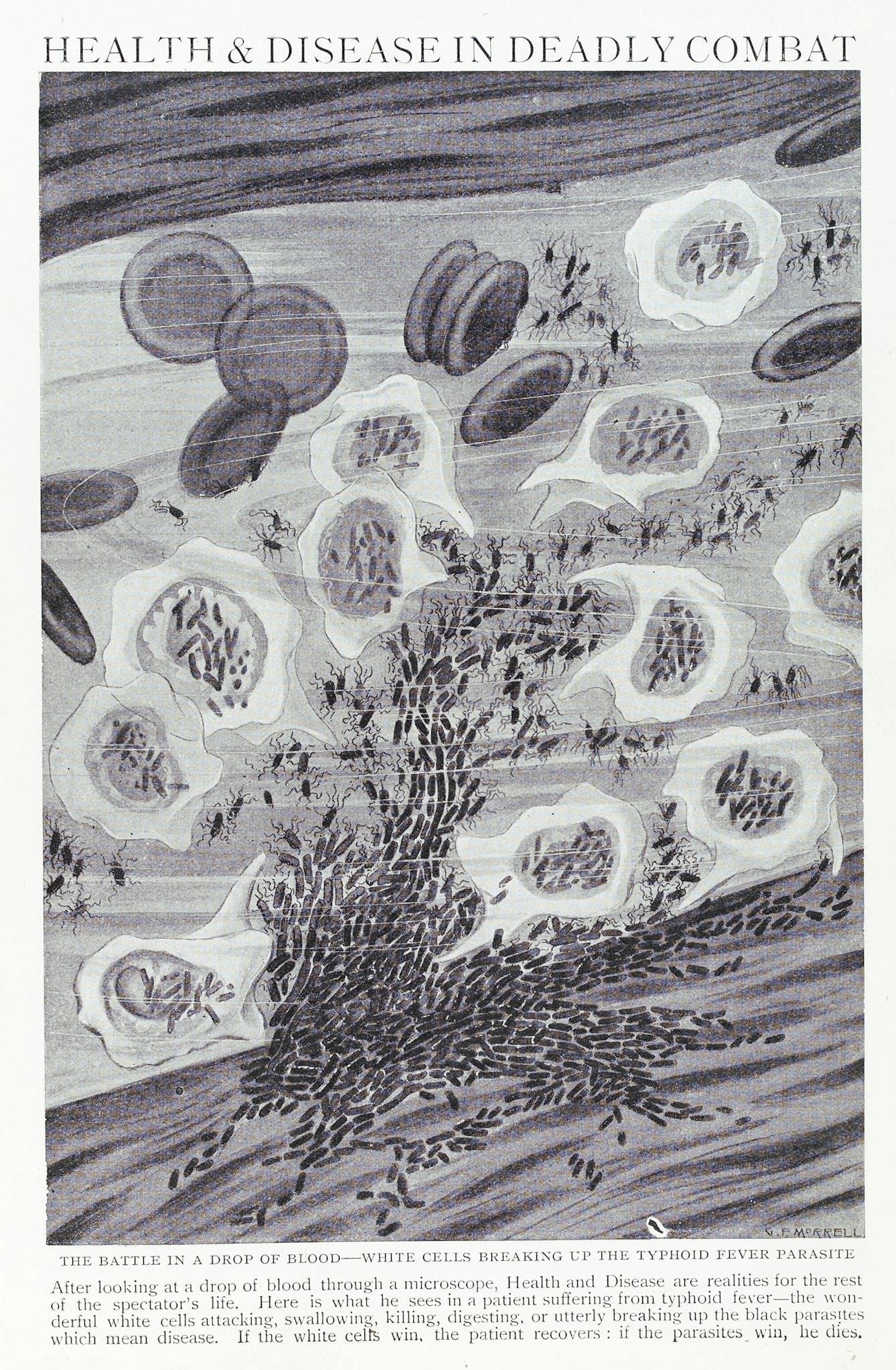

White blood cells attacking typhoid in the bloodstream, 1912.

Within a fortnight of Mallon’s capture, the New York press published her story, without revealing her name. Mallon was labelled a “human typhoid germ”, a “danger to the community” and a “walking typhoid fever factory”, further dehumanising a woman who had been arrested, incarcerated and medically examined without charge or trial. Mallon was soon confined on an island less than a kilometre square, where she was examined several times a week. She spent most of the rest of her life there.

In 1909 Mallon hoped to gain her freedom from North Brother Island at a hearing in the Supreme Court, an event that also allowed the press to reveal her name. They responded by inventing a new title, still used to describe a pariah or, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, “a transmitter of undesirable opinions or attitudes”: Typhoid Mary. The newspaper The American, while sympathetic to Mallon’s imprisonment, ran a feature under this title, illustrating it with a drawing of a cook tossing human skulls into a frying pan.

Mary Mallon is publicly named – and renamed – in The American, June 1909.

Mallon’s case was unsuccessful in the face of laboratory cultures from her own stools, which repeatedly showed the bacteria that caused typhoid. The Department of Health presented this as incontrovertible evidence that Mallon was a danger to society. Her own lawyer argued that Mallon’s constitutional right to due process had been violated. In essence, the two sides debated a thorny issue that remains relevant today: how do we protect the wider public’s health without infringing on individuals’ civil liberties?

After the appointment of a new health commissioner in 1910, Mallon was eventually freed on the condition that she no longer work as a cook. The new commissioner even helped her secure a job in a laundry. For the next two years Mallon seems to have avoided working with food. However, she may have found it difficult to earn enough income to support herself, or perhaps she simply wanted to return to her profession of choice.

In 1914, after having fallen off the Department of Health’s radar, Mallon used an assumed name to take up a job as a cook at a New York maternity hospital. It’s unlikely she deliberately set out to cause harm to those who ate her food. Instead, Mallon almost certainly didn’t believe the science she had been presented with and knew she would be prevented from working as a cook if she used her own name.

When 25 hospital staff contracted typhoid in 1915, and two died, the outbreak was again traced back to Mallon, who was returned to North Brother Island. There she remained, quarantined, until her death. In the intervening period, other healthy carriers of typhoid had been identified in the city, including two men who worked in the food business. These carriers were treated in a manner starkly different from that of Mallon.

A representation of typhoid infection from a French advertisement for disinfectant paper, 1890.

One of them, Belgian-born Alphonse Cotils, owned a New York bakery, in which he continued to work despite officially being forbidden to do so. When taken to court in 1924, Cotils received a suspended sentence. The judge acknowledged the extreme danger Cotils posed, but stated that he could not legally jail him “on account of his health”.

Did Cotils escape confinement due to his gender, his nationality or his successful business? Perhaps he wasn’t considered as much of a danger as Mallon, who had a reputation for being pathologically angry and acting irrationally. Official documents of the time show that Mallon was often described as an “Irish woman”, while other carriers were not usually identified by their race or gender. Comments about her personal appearance or demeanour were also common, while absent in the descriptions of others.

Mallon died on North Brother Island in 1938, 31 years after she was first taken there. Her death was reported by the Lancet medical journal, which described the woman who made her living as a cook as “a chronic typhoid carrier”. The man responsible for reporting her to the Department of Health concluded after her death that Mallon had a “curious career” as “the most famous typhoid carrier who ever lived”. It was, of course, not a career she ever chose to pursue.

About the author

Anna Faherty

Anna Faherty is a writer and lecturer who collaborates with museums on an eclectic range of exhibition, digital and print projects. She is the author of the ‘Reading Room Companion’ and the editor of ‘States of Mind’, both published by Wellcome Collection.