The pictures are striking and iconic, but the story behind them is far from black and white. Here, we profile 19th-century photographer Frank Rinehart’s remarkable portrayal of Native Americans.

Native Americans through the 19th-century lens

Words by Allison C Meier

- Story

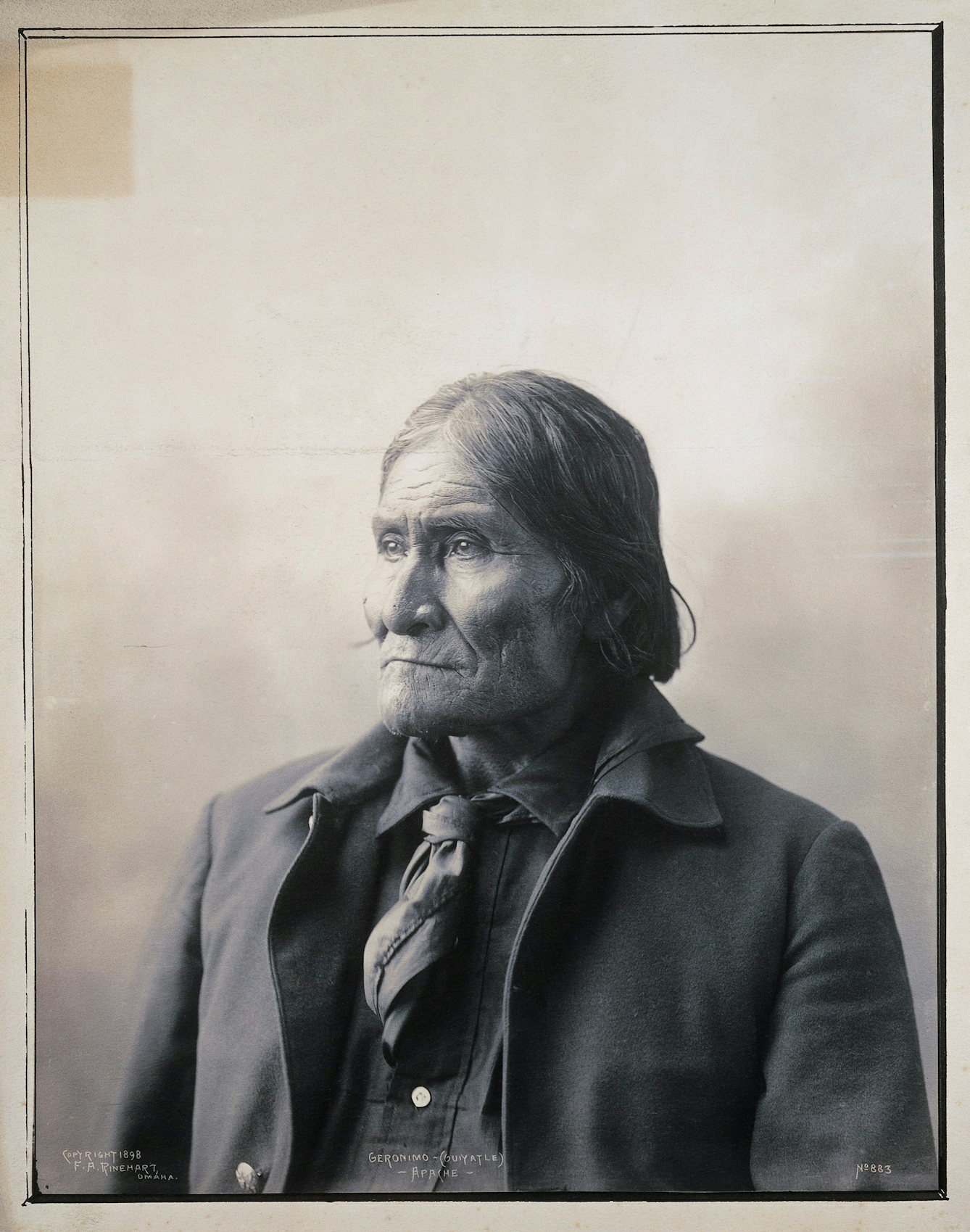

The 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska, modelled itself on the exuberant Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, right down to the Venetian lagoon with its swan boats, encircled by stately plaster architecture. However, the star attraction was the Indian Congress, a three-month gathering of around 500 members of 30 tribes, including the Apache leader Geronimo, then a prisoner of war at Oklahoma’s Fort Sill.

Portrait of Geronimo, the Apache chief.

It was intended, the organisers stated, to exhibit “the life, native industries, and ethnic traits of as many of the aboriginal American tribes as possible”. Yet the mock battles staged at the 5,000-seat grandstand only contributed to tropes and stereotypes.

Omaha’s world’s fair celebrated the development of the American West, a federally enforced progress that had displaced, killed and forcibly assimilated indigenous people. Exhibited as living displays at the exposition, they were presented as if on the brink of disappearance.

As souvenirs, visitors could buy a red hardcover photography book, emblazoned with the title ‘Rinehart’s Indians’, an embossed spear, a shield and a feathered headdress. Inside, the book’s introduction proclaimed:

“The camera of Mr Rinehart… was ever busy recording scenes and securing types of these interesting people, who with their savage finery are rapidly passing away. In a remarkably short time education and civilization will stamp out the feathers, beads and paint – the sign language and dancing – and the Indian of the past will live but in memory and pictures.”

Portrait of Henry Wilson and his wife, Americans of the Mohave.

The creator of the following 46 portraits – the Omaha-based Frank Rinehart (and his assistant Adolf Muhr, who may have taken many of them) – was the fair’s official photographer.

Most 19th-century documentarians of indigenous people treated them as ethnographic specimens – for instance, anthropologist Franz Boas used photography for craniometric and anthropometric measurements in studies of the Kwakiutl. Others portrayed Native Americans as either primitive brutes, or noble savages, supporting the manifest destiny belief in American expansion into their land and homes.

However, in Rinehart and Muhr’s fairground studio, their eight-by-ten glass negative camera pictured their subjects like individuals without exoticisation.

The largest collection of Rinehart’s photographs is at Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas. Several platinum prints are in Wellcome Collection.

Portrait of Naiche, hereditary chief of the Chiricahua.

Included are those of historic figures such as Naiche, the last hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache, a hat with the US Indian Scout insignia above his weathered features. Others are anonymous, such as a Kiowa man photographed in regalia against a painted studio backdrop of bookshelves and curtains.

In each, there is a dignity to the subject, even as Rinehart’s camera romanticises their appearance by contrasting their traditional dress with the Victorian studio.

An American of the Kiowa tribe.

In ‘Beyond the Reach of Time and Change: Native American Reflections on the Frank A Rinehart Photograph Collection’, a 2005 book of essays edited by Simon Ortiz, James Riding writes:

“Whether intentionally or not, Frank Rinehart and other photographers of the era propagated a fantasy of Indians as living in a static immutable state. The presence, on the other hand, of Indian people in Rinehart’s photographs exudes defiance, pride, and nonconformity with US norms at a time when it was extremely difficult and unpopular to be Indian. The desire of Indians to maintain their distinctive cultural and personal identities in a rapidly changing and often brutal world is reflected in their dress, confidence, and bearing.”

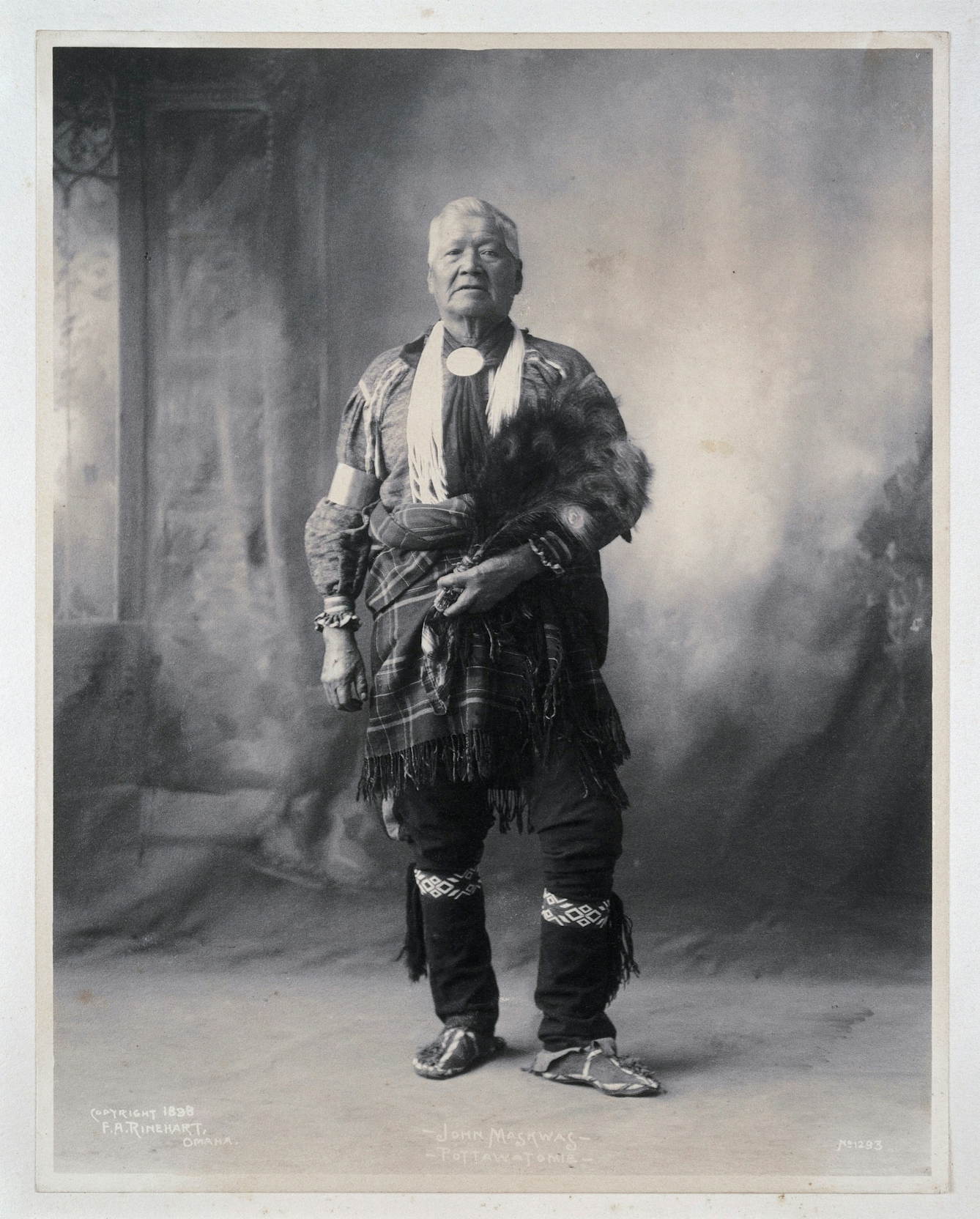

Portrait of John Maskwas, a Potawatomi Indian.

In the previous century, the Indian Removal Act, signed by President Andrew Jackson on 28 May 1830, led to the forced relocation of indigenous people. By the end of the 19th-century, Indian Schools were further enforcing the erosion of language, customs and dress.

Rinehart’s hundreds of photographs are invaluable records, and strikingly beautiful, but are part of this imperialism.

A copy of ‘Rinehart’s Indians’ is at the New York Public Library, along with many of his platinum prints. The captions aim to guide the viewer flipping through its pages.

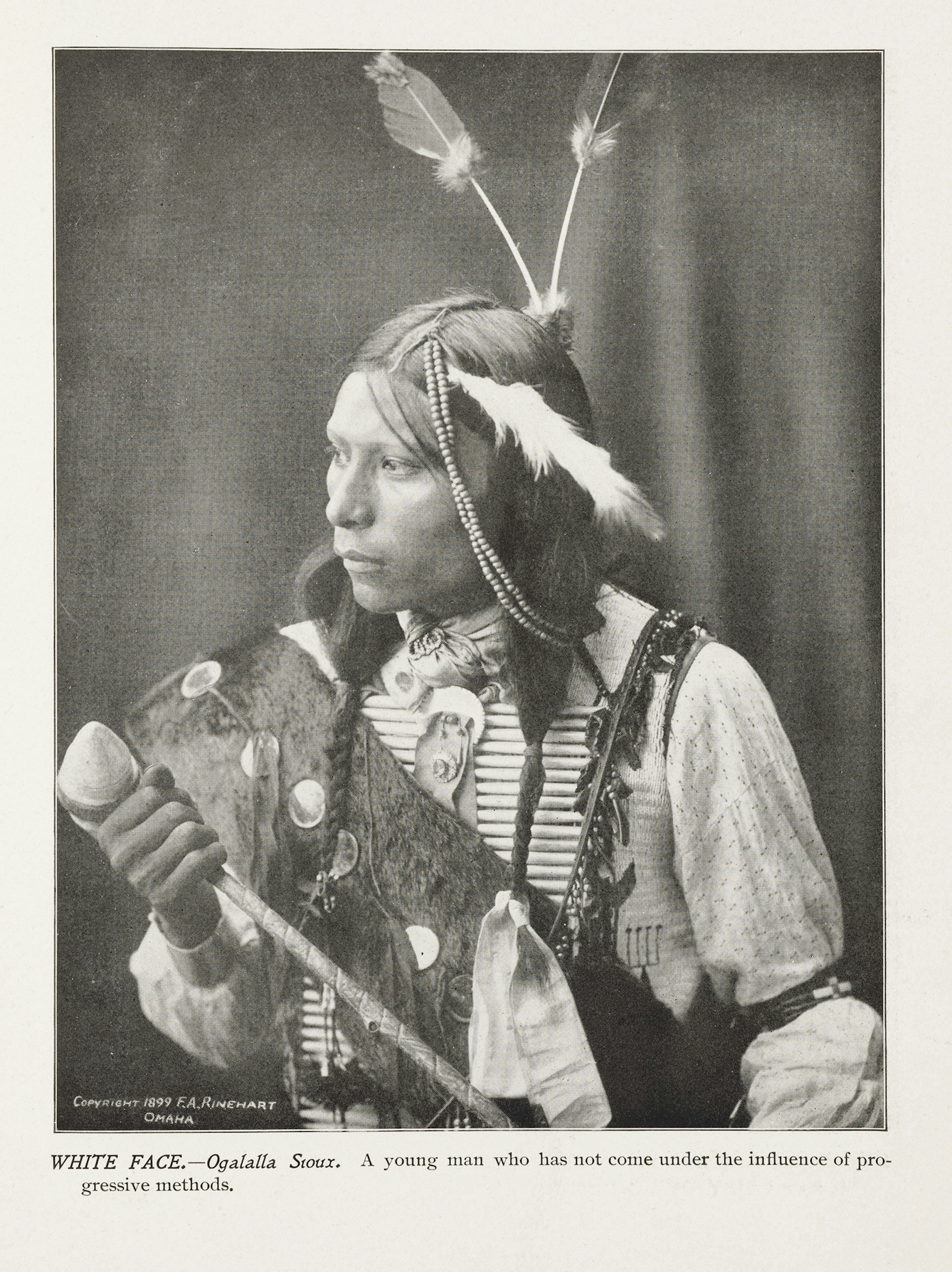

Portrait of White Face of the Oglala Sioux.

White Face of the Oglala Sioux, whose dynamic pose with his face angled away, and one arm raised toward the camera, is accompanied by the text: “A young man who has not come under the influence of progressive methods.”

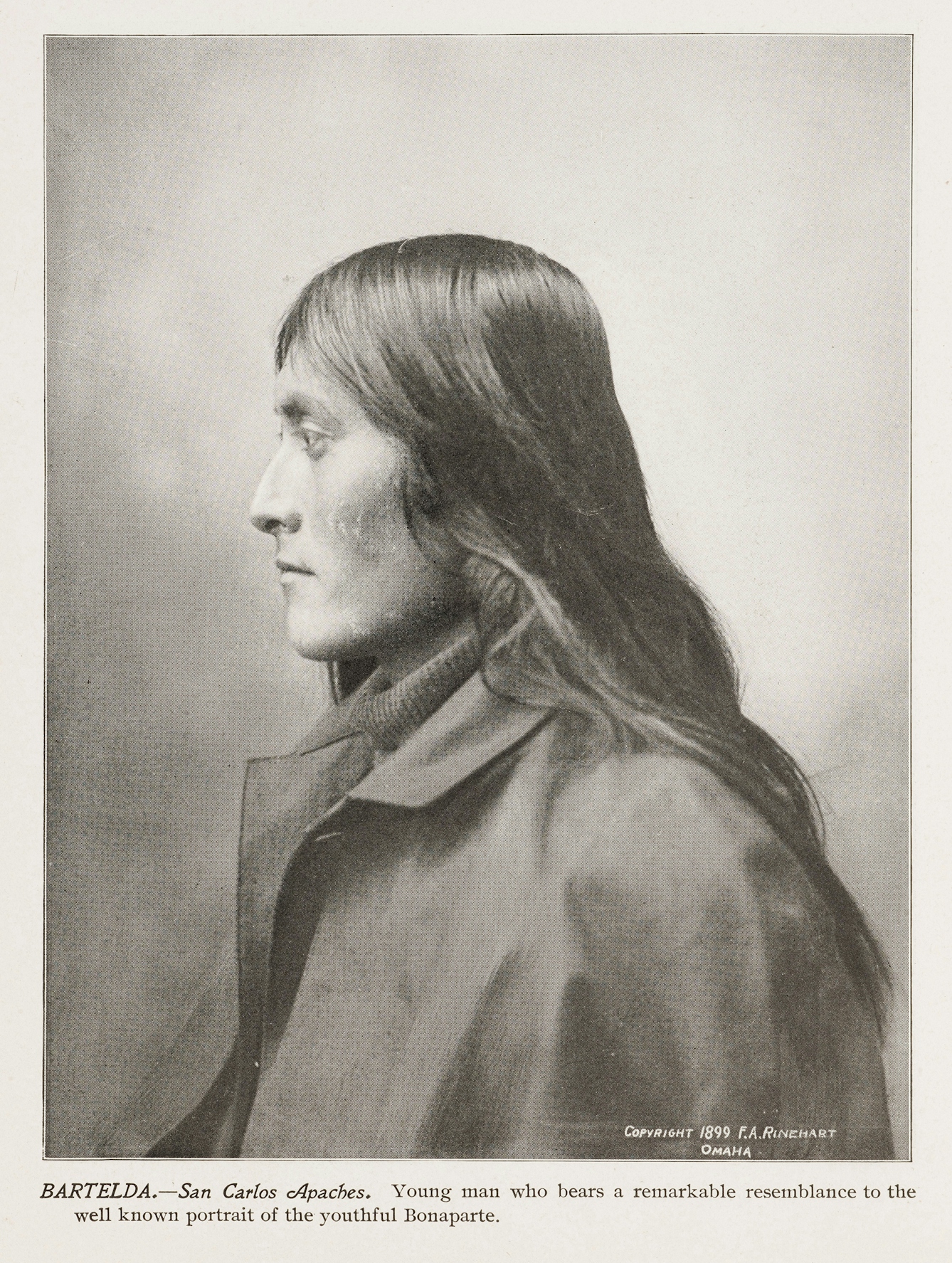

Bartelda, a San Carlos Apache, is in profile, his long hair flowing over his western-style coat. The caption suggests the Napoleon-esque pose as another level of Eurocentric framing: “Young man who bears a remarkable resemblance to the well known portrait of the youthful Bonaparte.”

Portrait of Bartelda of the San Carlos Apaches.

The Indian Congress members are not given a voice in this book. Yet in a 1979 article for ‘Montana: The Magazine of Western History’, Robert Bigart and Clarence Woodcock point out: “Ironically… the gathering that was to observe the memory of the American Indian showed the means of Indian survival: intertribal communication and Indian resistance to cultural change.”

These expressive photographs made Rinehart famous, and may have influenced more empathetic portrayals by photographers such as Edward Curtis (especially as Muhr later managed Curtis’s studio). Significantly, just a few years before the Omaha fair, Ponca chief Standing Bear had successfully gone to the United States District Court in Omaha in 1879 to argue that Native Americans are “persons within the meaning of the law”.

The impact of these photographs on public perception of that humanity is hard to gauge, but there is something powerful in the images of a supposedly ‘vanishing’ people defiantly surviving.

You can now read the second part of this story ‘Native Americans and the dehumanising force of the photograph’.

About the author

Allison C Meier

Allison C Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer who focuses on history and visual culture. She was previously Senior Editor at Atlas Obscura and more recently a staff writer at Hyperallergic.