The line between confession and counselling has been blurred for centuries. In fact, confession in the Middle Ages was thought to improve physical and mental wellbeing and was even used as a treatment for all sorts of illnesses. Katherine Harvey explores how confession was regarded in the medieval period.

The benefits of Catholic confession

In recent years, the Vatican has reminded its followers that ‘confession is not therapy’, and urged them not to confuse the confessional with a psychiatrist’s couch. But the blurring of boundaries between the two practices is a centuries-old phenomenon: long before the birth of Freud, people in the Middle Ages shared intimate details of their lives with priests.

Medieval confession wasn’t therapy, but it was therapeutic: besides the obvious spiritual benefits, it was thought to improve both physical and mental wellbeing.

Roman Catholics have been required to make regular oral confessions to priests since 1215, when the Fourth Lateran Council ruled that they must do so at least once a year. The same council pronounced on the relationship between sickness and sin:

As sickness of the body may sometimes be the result of sin… we command physicians of the body, when they are called to the sick, to warn and persuade them first of all to call in physicians of the soul [ie, priests] so that after their spiritual health has been seen to they may respond better to medicine for their bodies; for when the cause ceases so does the effect.

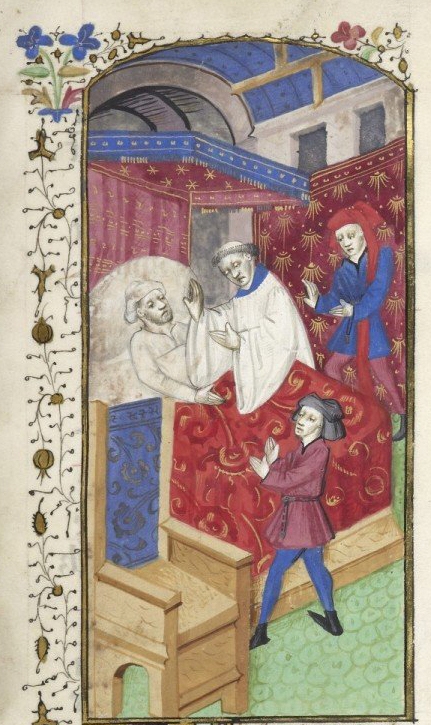

It was important to be attended by a priest when you were sick, as this deathbed scene shows.

If sin could cause disease, there must be a literal connection between spiritual and physical healing. And confession – which treated the spiritual disease of sin – could also treat bodily diseases caused by sin. Consequently, confession was essential for the dying, but also beneficial to those who might recover, and to those who hoped to avoid sickness altogether.

Medieval priests

This deathbed scene features Godfrey of Bouillon with his priest.

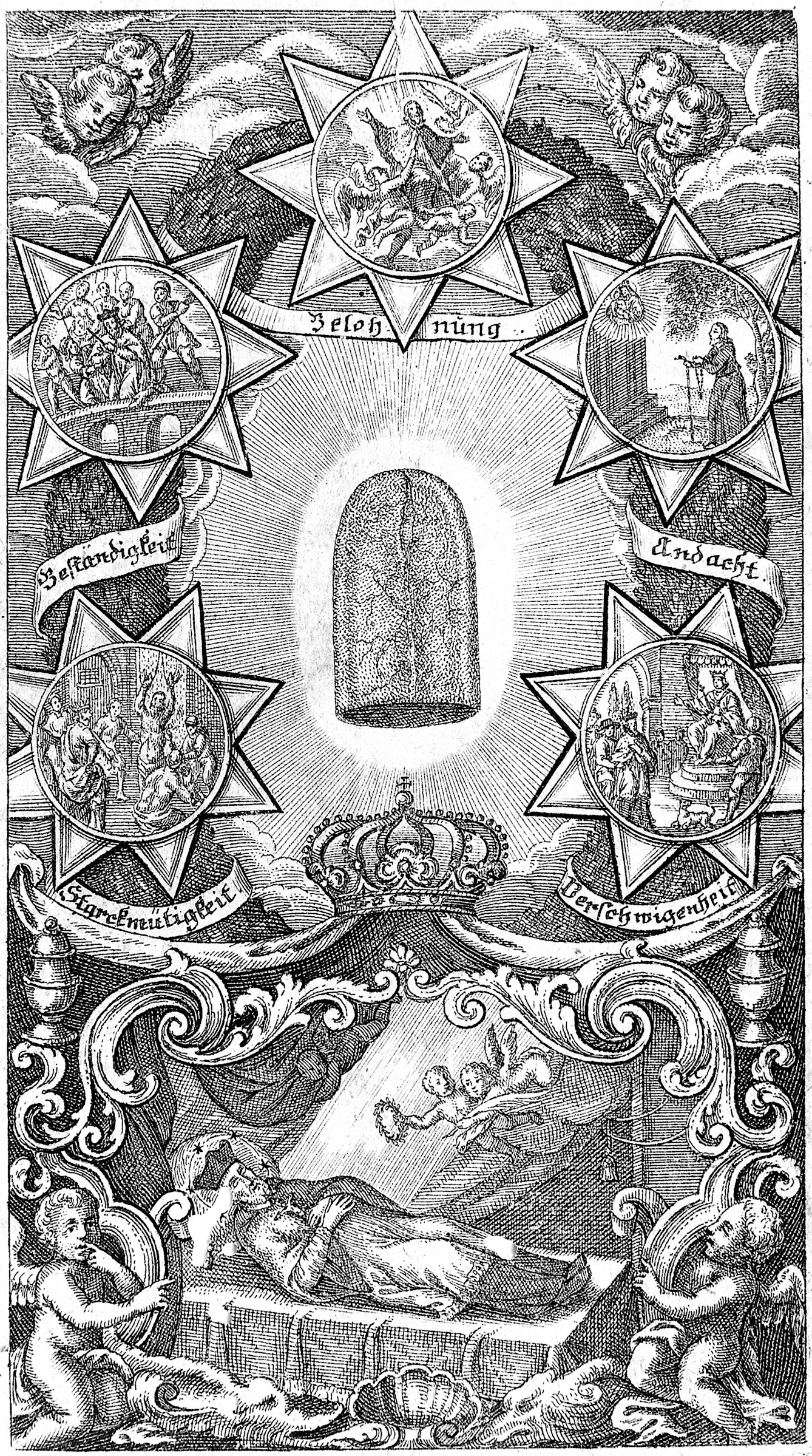

The medical benefits of confession are related in this etching, which explains that "as medicines are necessary to restore decayed health, so is Penance to heal ye maladies & sores of sin".

A woman gives her confession, potentially helping both her soul and her health.

The healing power of penitence was also reflected in the language that churchmen used to describe confession: they compared it to common medical treatments such as purging, blood-letting and surgery. William of Auvergne, Bishop of Paris from 1228, used a particularly memorable metaphor:

Vomit is the emptying of the belly via the mouth… In the same way, the belly of the heart, or conscience, is emptied or relieved from vices or sins, by the agency of the mouth, by speaking or revealing these things to a priest. Therefore, just as someone with an upset stomach, straining to expel what is harmful or unsuitable to it, distends his belly and opens his mouth wide to get rid of it, so too someone with an upset to a holy and noble conscience strains and searches the belly of his heart to throw out and expel detestable and filthy vices and sins, opening his mouth wide for them to leave via the words of confession.

This powerfully repulsive image revealed a keen understanding of medical theory. In an age of humoral medicine, sin was just another excess in need of expulsion. And since confession often involved weeping, it could provoke purgation that was both literal (tears) and metaphorical (sin).

Better out than in: confession was like vomiting out the conscience.

But if confession cured the sick by removing the sin that caused their illness, it also had psychological benefits comparable to modern therapy. Medieval physicians understood that the mind influenced the body. They believed that unruly emotions could cause physical illness, and treatises on healthy living advised readers to strictly manage their emotions. Doctors were careful to reassure their patients, believing that a positive attitude made recovery more likely. Some even fretted that telling a patient to confess would decrease their chances of recovery, since they would assume that death was imminent.

Despite this risk, confession was often incorporated into the healing process. Medieval hospitals required their patients to confess on arrival, and at regular intervals thereafter. In one dramatic example from the 13th century, when Archbishop of Canterbury Hubert Walter was on his deathbed, his doctor (who was also a priest) advised him to confess his sins. When Hubert did so, “the fire of his remorse and charity” dissolved the moisture in his brain, producing both floods of tears and temporary relief from his fever. The Archbishop was then able to eat and drink, and to make his will. Hubert’s recovery was brief – he died the following day – but his case offers an intriguing insight into medieval beliefs about confession and how it was thought to impact on the body.

Weeping could help to expel an excess of liquid.

Remarkable longer lasting recoveries after confession were recounted, too. Gundulph, Bishop of Rochester from 1077, heard the confession of a dying woman. She experienced “heartfelt contrition”, and after “the wholesome remedy of penitence was applied… [she was] fully restored to health”.

Confession could even play a part in healing miracles. Odo de Beaumont, who contracted leprosy from a prostitute, was cured after he confessed his sin, fasted, and promised to go on pilgrimage to Thomas Becket’s tomb.

Stories like this suggest that medieval folk viewed the relationship between body and soul very differently to us: physical, mental and spiritual wellbeing were inseparable, and the health benefits of confession seemed to prove the power of God.

In pictures

In this French manuscript illumination, a hermit confesses his sins to a bishop.

Confession was not so healthy for St John Nepomuk, who was executed by the King of Bohemia for not telling the king what the queen said in the confessional.

This English manuscript depicts a priest hearing confession during Lent.

In the 21st century, conversely, the needs of body and soul often seem to exist in opposition, and so to compare confession to therapy is to reduce its significance – at least in the eyes of the Church.

But while clerical perspectives on confession have changed, it seems that the faithful have always derived something more than spiritual succour from the practice. If confession is not, and has never been, the same as therapy, it has long been therapeutic – and, despite the best efforts of the Vatican, will surely continue to be.

About the author

Katherine Harvey

Dr Katherine Harvey is a medieval historian based at Birkbeck, University of London. She is the author of ‘The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages’ (Reaktion, 2021), a Sunday Times Paperback of the Week. Her writing has appeared in publications including BBC History Magazine, History Today, The Sunday Times, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Atlantic.