An 11th-century poem of love, lust and possibly gruesome death still resonates today. Explore its history and the stunning illustrations used to help tell the romantic tale.

Lovesickness and ‘The Love Thief’

Words by Julia Nurse

- Story

We’ve been using poetry to tell each other (and the world) about our love from ancient times. Some poems transcend time and cultures more than others, morphing as they travel: the ‘Chaurapanchâsika’, or ‘The Love Thief’ is a classic example.

This passionate 11th-century Sanskrit 50-stanza lament tells the story of a Brahman sentenced to death for loving a Maharaja's daughter. It’s based on the Kashmiri poet Kavi Bilhana's own experience: he wrote the work in prison in praise and recollection of his lost love.

Though the original no longer survives, the verse survived and continues to be popular today as a significant example of medieval Indian poetry. Both oral and written copies helped to perpetuate the poem’s success – versions that appeared in North India ended with the narrator facing execution, while those produced in South India had happier endings where the couple eventually marry.

The woman the poet loved is described in steamy language - her imprisoned lover recalls her "warm dusk breast / Where, like thy happy pearls, I took my rest."

So why did this particular verse travel so well and for so long? The blurred boundaries of the spiritual and the sensual that are visible in this poem are a characteristic of all Indian love poetry. What is unusual about ‘The Love Thief’ is its continuing popularity and survival into the 21st century. Its appeal was not only in the universally popular subject of love, but apparently in the accessible illustrative way in which it was written.

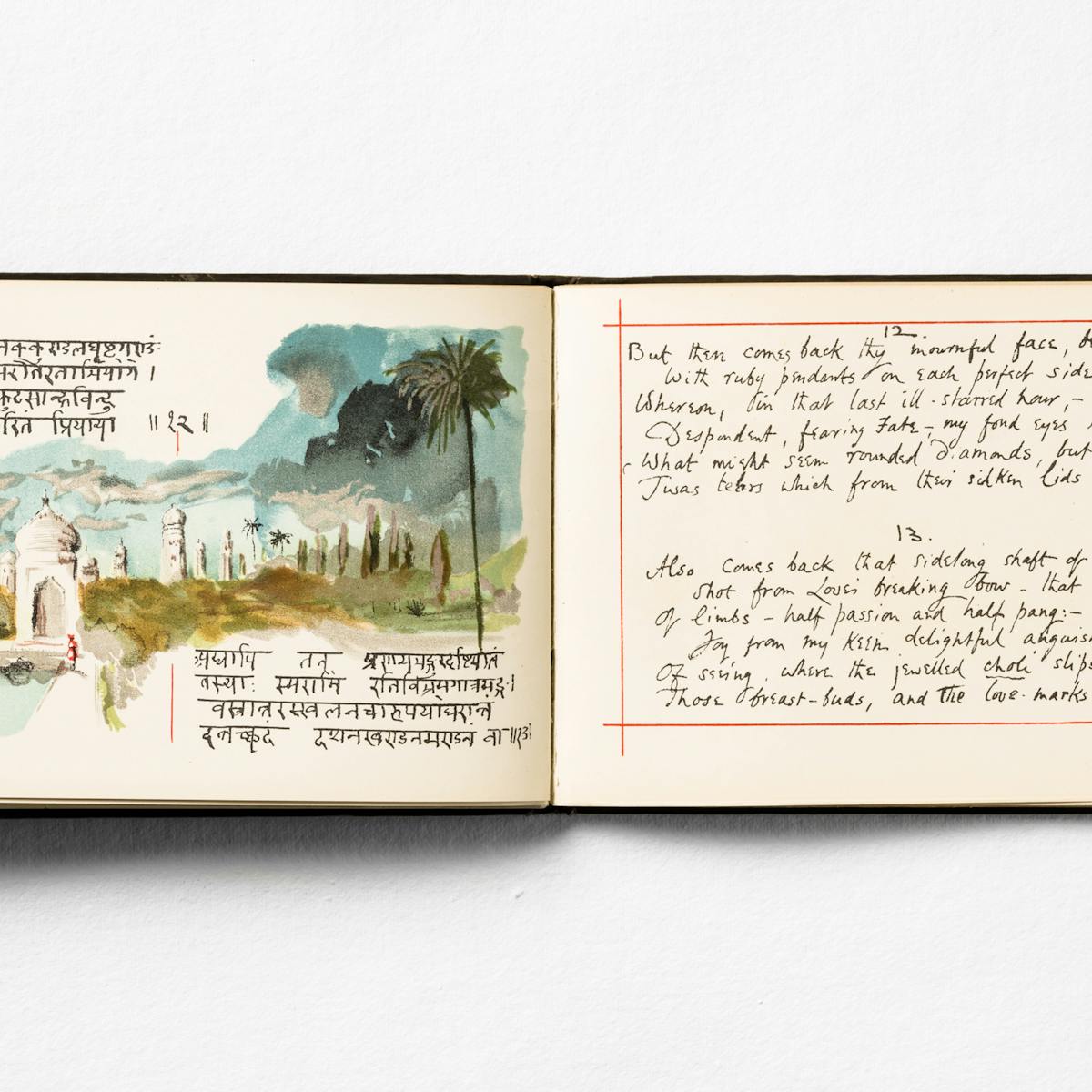

The French rediscovered and translated the poem in 1848, opening it up to Western European audiences. In turn, poet and journalist Sir Edwin Arnold wrote and illustrated an English version in 1896, thanks, in part, to British colonialism: the foreword explains that Arnold’s copy was based on a 1798 edition that surfaced in the East India Company library in Whitehall (now held at the British Library).

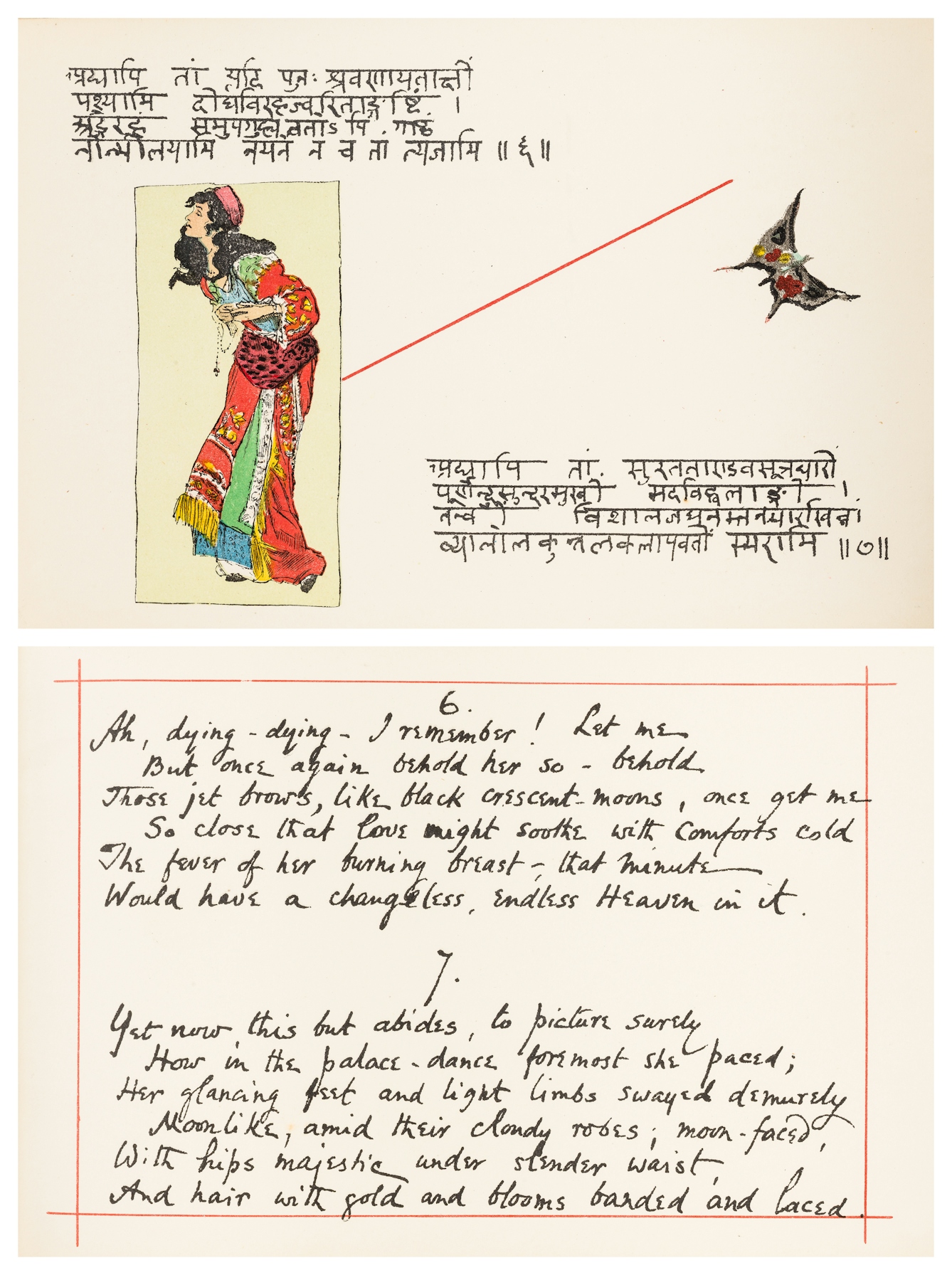

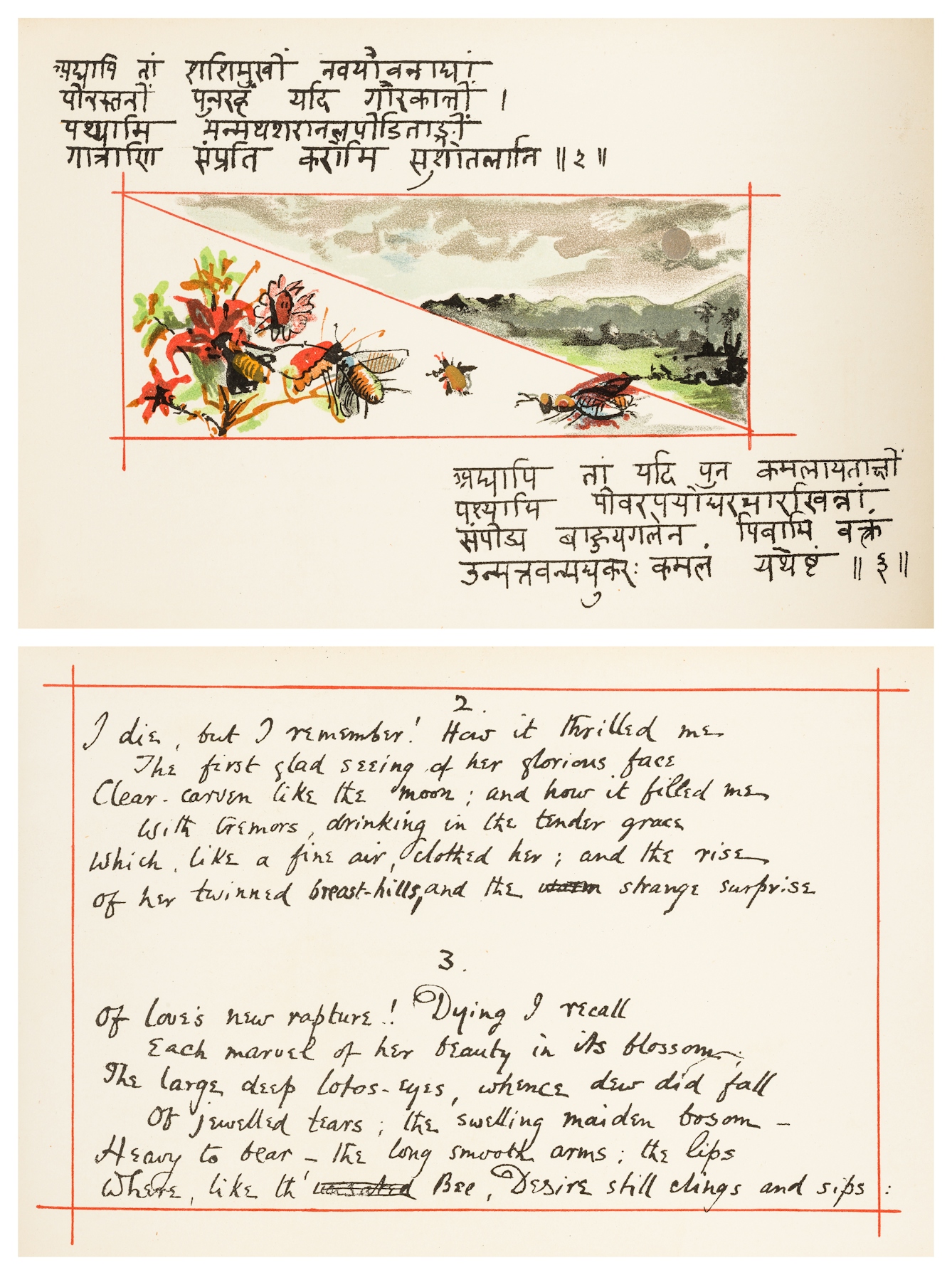

The imagery, metaphors, and ideals of romantic love abound throughout the verses and are enhanced in Arnold’s version by his accompanying watercolour illustrations. Included are illustrations of the Maharaja’s palace, the princess gripped by love’s power clutching “the fever of her burning breast”, and numerous flowers and plants.

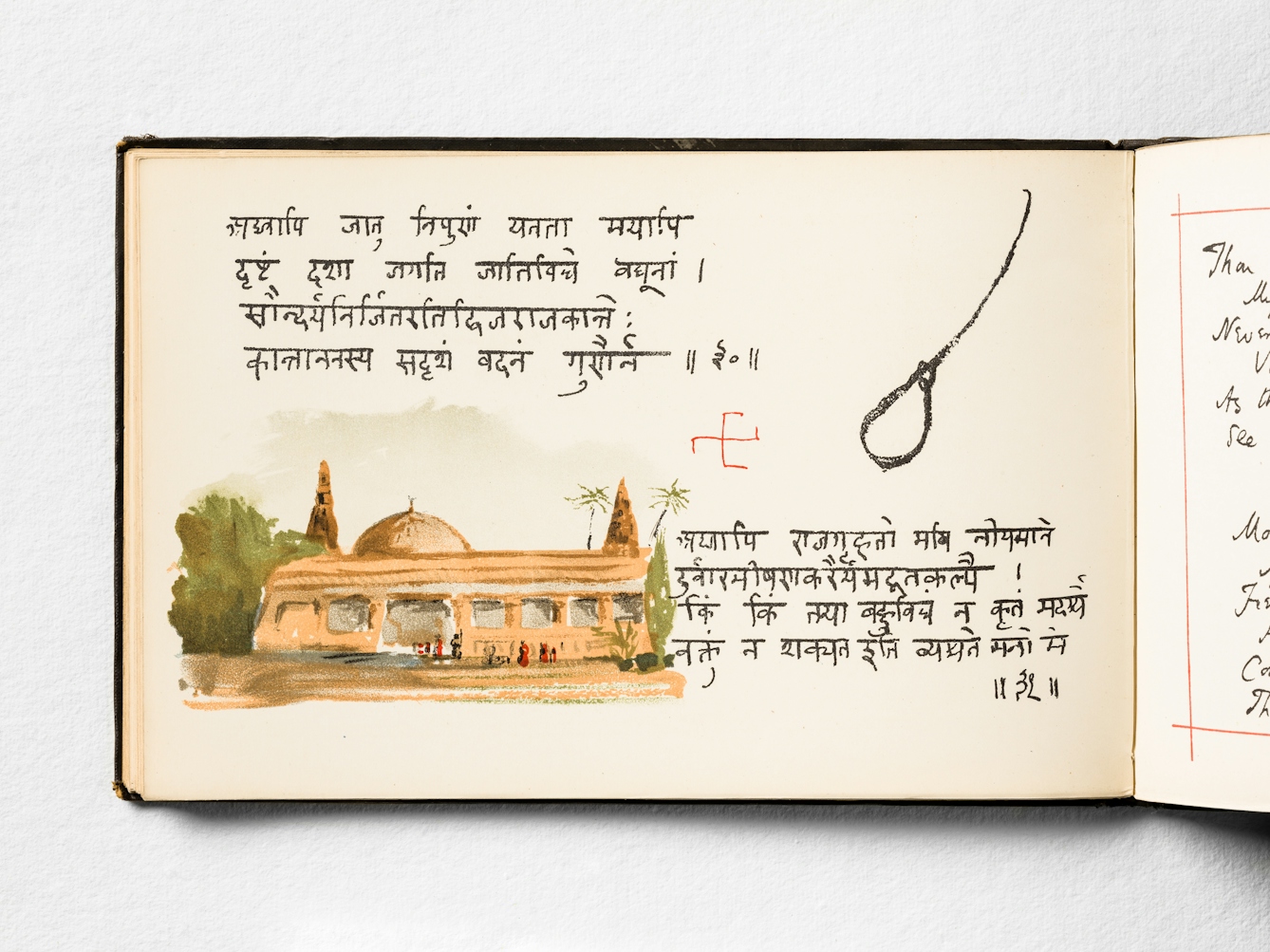

Death hangs over the poet and violent images like this noose accompany the sensual images of nature.

Broken-hearted grief is dramatically depicted alongside the recurring butterfly symbolising remembrance.

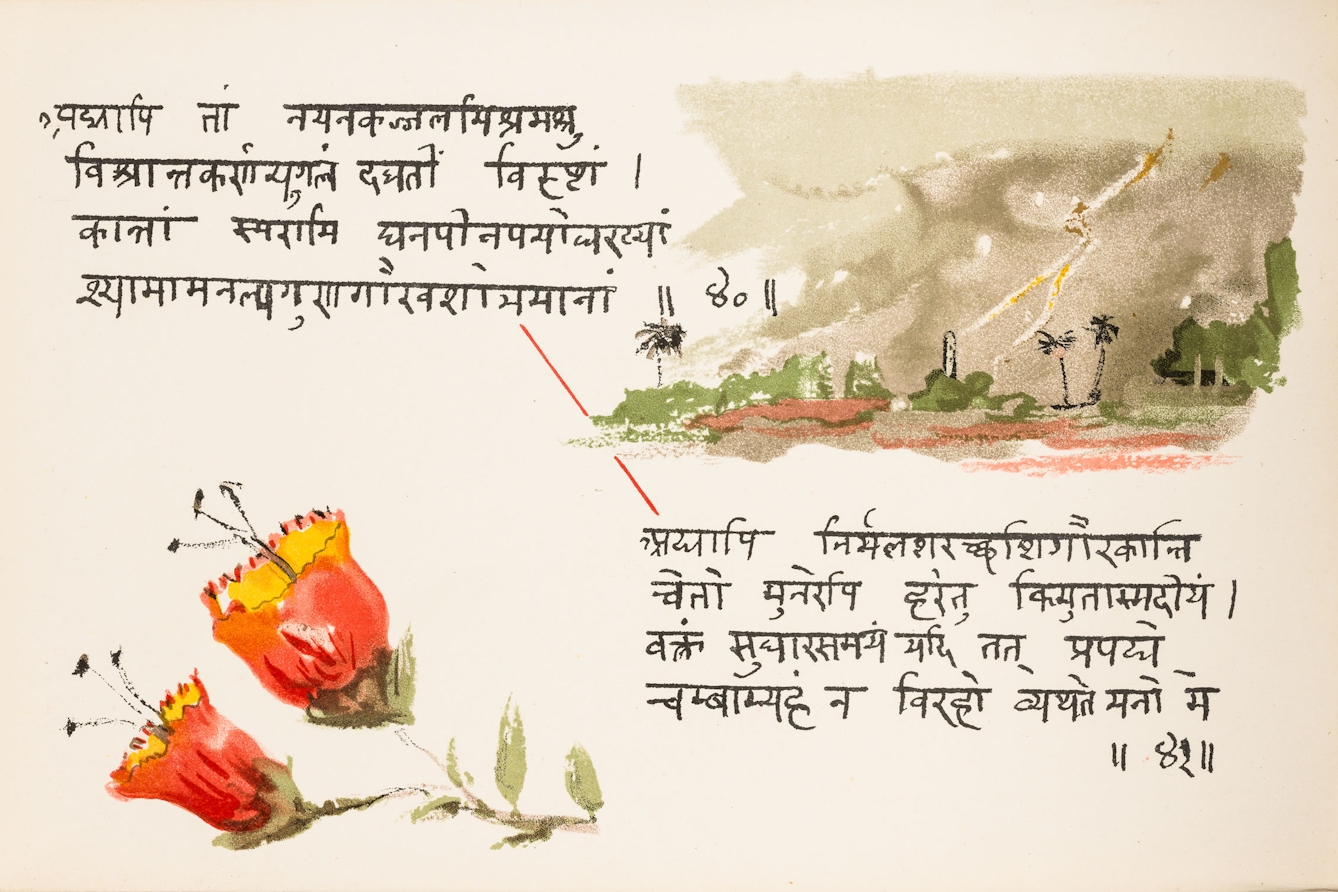

As was typical of Indian love poems, nature is not just described, but personified in the verse:

Of love’s new rapture! Dying I recall

Each marvel of her beauty in its blossom;

The large deep lotos-eyes, whence dew did fall.”

Lightning picked out with gold illustrates how passionate the loved woman could be, whilst the vivid flowers "recall her red lips smiling".

According to Arnold’s foreword, the repetition of the Sanskrit word “adyapi” (“remember”) reinforces the theme of reminiscence throughout and provides a pleasing structural pattern to the verse. The “melodious and ingenious monotony of fanciful passion” that this repetition created was echoed in Arnold’s recurring butterfly illustration.

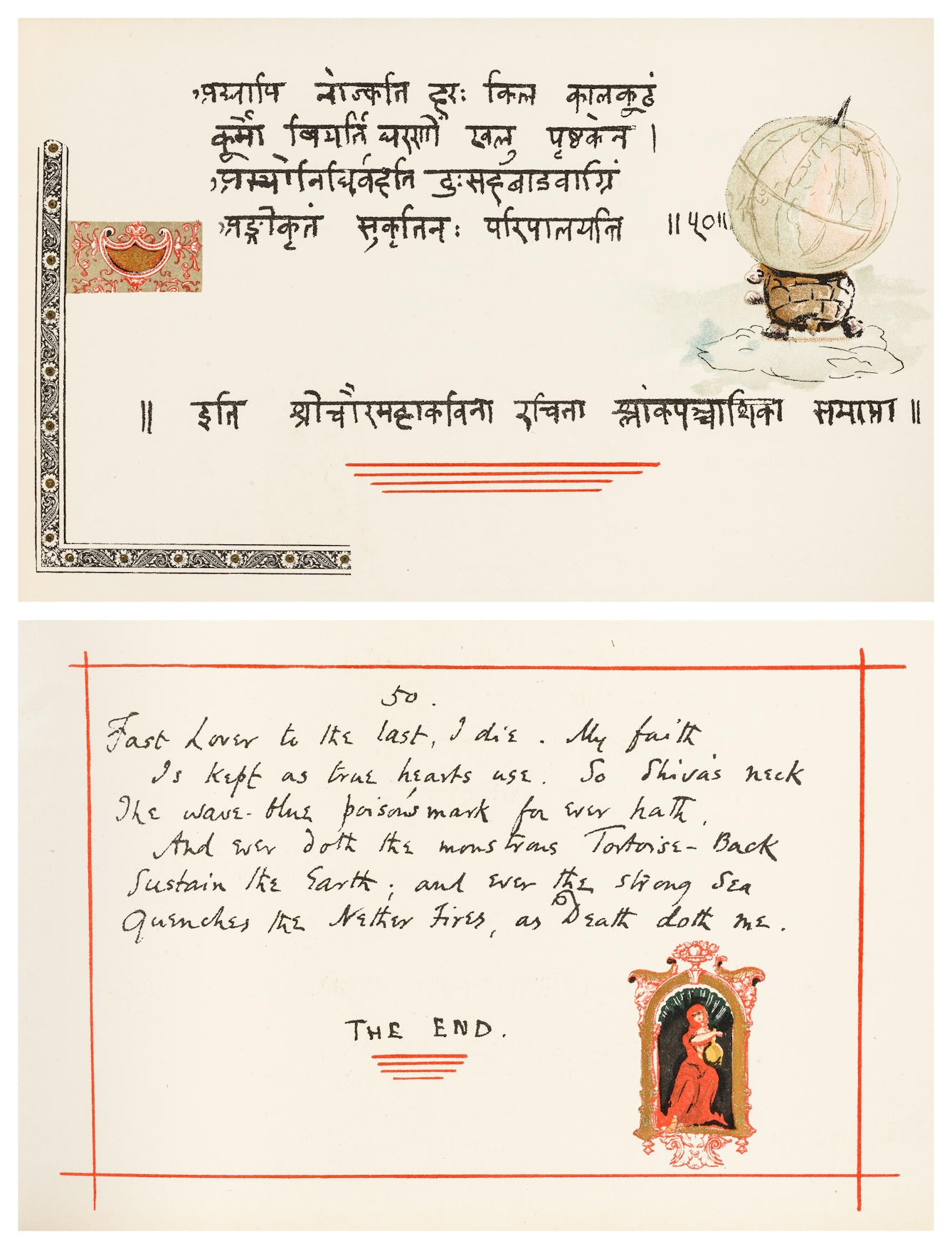

Nature appears from beginning to end. The final page of the poem shows a stoic tortoise bearing the weight of the world on its back, accompanying the dramatic conclusion:

And ever doth the monstrous Tortoise-Back

Sustain the Earth; and ever the strong sea

Quenches the Nether Fires, as Death doth me.”

Eternal love is suggested by the stoic world-bearing turtle of mythology shown at the poem's end.

If this enduringly popular poem sounds familiar to you, there are lots of possible places you may have come across it. The 20th century saw numerous editions of the verse: Edward Powys Mathers published a version entitled ‘Black Marigolds’ in 1919, which was quoted extensively in John Steinbeck’s ‘Cannery Row’ of 1945; in the 1940s, two Tamil films appeared; in 1967, a book of 16th-century Indian miniatures from the Gujarat Museum Society at Ahmedabad were published illustrating the poem; in 1971, the Sanskrit scholar, Barbara Stoler Miller, popularised the text further with her ‘Phantasies of a Love Thief: The Caurapancasika Attributed to Bilhana'.

Bees, flowers and the moon are just some of the classic comparisons still made in love poetry many times since Bilhana created his love lament a thousand years ago.

The tradition continues into the 21st century – most recently in a 2013 translation by Dawn Corrigan. Nine major UK university libraries still hold a copy of the poem and it is no surprise to find one lurking on the shelves of our Wellcome Library, which purchased a copy of Arnold's edition in 1982.

The original may have been written some ten centuries ago, but the evocative way in which the ‘Chaurapanchâsika’ describes love still retains the power to stir the modern reader:

Oh me! I was the bee who sucked his pill

From fragrant chalice of that gold-kissed flower

Breast deep. Know I not well how it did thrill

Beneath mine eager clasping in that hour

When love waxed well-nigh cruel in quick kisses,

And passion welcomed hurts that mixed with blisses.”

[Translation courtesy of Arnold’s text, though it varies considerably in other editions.]

About the author

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. She currently runs the Exploring Research programme, and has a particular interest in the medieval and early modern periods, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.