When a pharmacist tried to develop a scale to measure the heat of chillies, his results ended up lukewarm.

Chillies and the trouble with Scoville

Words by Danny Birchall

- Story

Carried in the boats of European colonisers, chillies travelled around the world so fast that they met themselves coming back. In 1776 Dutch botanist Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin dubbed the family of bonnet-shaped chilli cultivars that includes habanero peppers Capsicum chinense in the mistaken belief that it had originated in Asia.

The original chilli: the wild chiltepin plant.

In fact, like all chilli peppers, it came from the New World. Beginning in the fifth millennium BCE, native Mesoamericans cultivated and created new varieties of the wild chiltepin plant, using their fierce flavour for culinary, medical and religious purposes.

Spanish and Portuguese traders also found the plants attractive. Within two centuries of Columbus’s arrival in the western hemisphere, chillies had spread so far and wide that many cultures assumed that they were native ingredients. Transported by sea, cultivated by monks and rapidly adapted into regional cuisines, there are today over 50,000 different identifiable human-created chilli cultivars, from the Carolina Reaper to the humble bell pepper.

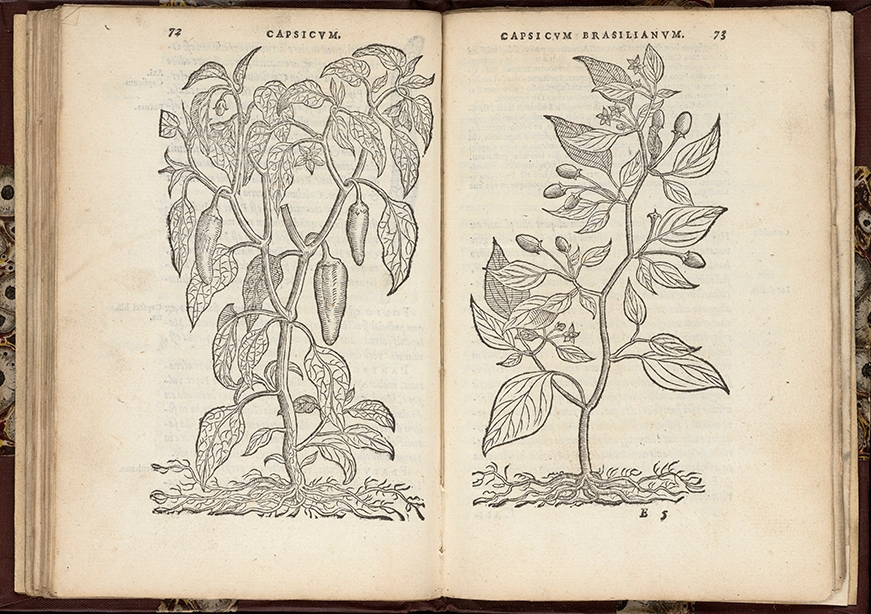

An illustration of a chilli pepper plant from botanist Nicolás Monardes’s 1574 survey of New World plants.

Fruity warmth or intense burn

All chilli peppers have one thing in common: a spicy heat. And we like to know how hot a chilli is before we eat it: whether to expect the fruity warmth of a jalapeño or the intense burn of a habanero.

Enter Massachusetts pharmacist Wilbur Scoville, who introduced in 1912 what he called the ‘organoleptic test’, now better known as the basis for the Scoville Scale, which measures the heat of chillies. Dried peppers are dissolved in alcohol to isolate the active capsaicinoid compounds and successively diluted in sugar water until a panel of trained tasters can no longer feel the heat. The results are reported in Scoville heat units (SHU), giving that jalapeño a rating of 3,500 to 8,000 SHU. The habanero could be up to a hundred times hotter at 100,000 to 350,000 SHU.

Pharmacist Wilbur Scoville created the ‘organoleptic test’ for measuring the heat of chillies.

Large numbers and scientific-looking acronyms notwithstanding, Scoville’s method isn’t actually that objective. Even trained tasters have a subjective experience, and the tasting palate becomes accustomed to heat, reducing the effect of further chillies. Today, analytical chemists use high-performance liquid chromatography to detect pungency, and translate the results back into Scoville units.

But is one kind of measurement enough? In a recent paper for the journal ‘Appetite’, researchers Ivette Guzmán and Paul W Bosland identified five different sensory characteristics of chilli peppers: development, duration, location, feeling and intensity. The build-up of sensation, the time that sensation lasts, the part of the mouth in which the heat is felt, and the sharpness or flatness of the heat are all taken into account, along with the intensity, still measured in SHU. The heat of a jalapeño is felt on the tongue and lips, while a habanero delivers its payload at the back of the throat.

Fresh peppers: red habanero on the left, green jalapeño on the right

Guzmán and Bosland’s method is not only sensitive to the presence of different varieties and quantities of capsaicinoid compounds and their complex relationship to human taste receptors. It also provides a basis for the food industry to analyse chilli varieties for their suitability for the cuisines of different cultures. As they point out, Asian diners prefer an intense, sharp heat that comes on rapidly and dissipates quickly, while Hungarian paprika has a moderate buildup of flat heat that is preferable in a Central European goulash.

But perhaps some things about chillies cannot be measured at all? The ‘facing-heaven pepper’ is both ornamental and widely used in Sichuan cooking: its poetic and aesthetic qualities bring something to every dish cooked with it, beyond its merely chemical properties. Widespread human cultivation has brought a glorious and abundant variety to the chilli pepper, a variety that deserves to be recognised and celebrated.

About the author

Danny Birchall

Danny is Wellcome Collection's Digital Content Manager.