James Morison's campaign against the medical establishment inspired a wave of caricatures mocking his quack medicine.

Graphic battles in pharmacy

average reading time 4 minutes

- Serial

In the 1830s, the medical establishment declared war on quack remedies. Public enemy number one was James Morison and his Hygeian Vegetable Universal Medicine.

Morison promoted an overarching medical theory in which all diseases originated from impurities in the blood. Morison’s pills, advertised by a team of agents known as Hygeists, would supposedly clarify the blood and therefore cure all diseases. His headquarters, the British College of Health, at 33 Euston Road, London, artfully presented Morison as the head of a learned institution rather than the manufacturer of dubious cures.

Mr Morison the Hygeist.

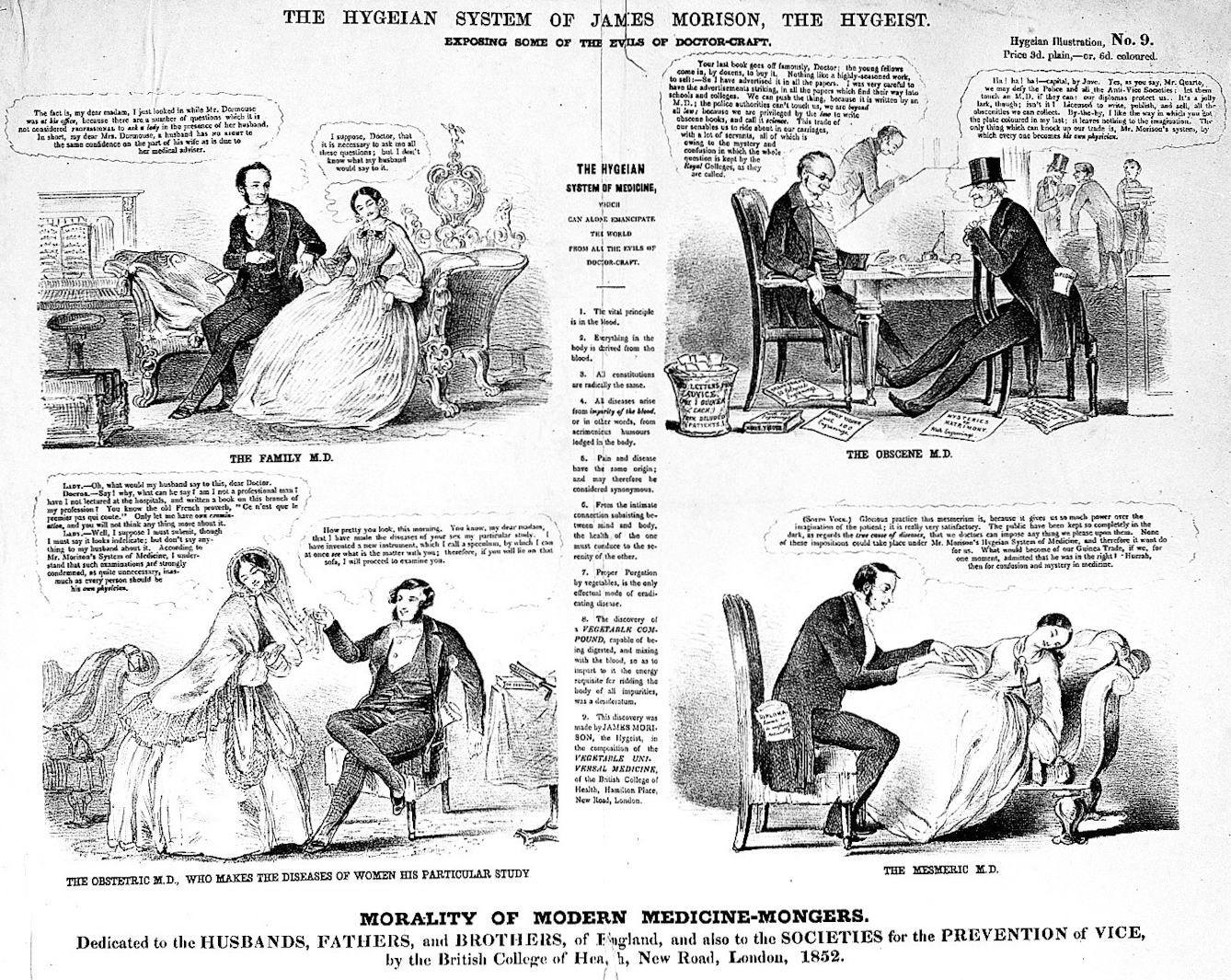

In turn, Morison attacked the medical establishment for its reliance on chemicals and mercury in contrast to his purely vegetable remedies. He commissioned at least 11 promotional Hygeian illustrations, with titles such as ‘Downfall of the Doctors’ and ‘Morality of Modern Medicine-Mongers’. Officially priced at 3 pence (6 pence for coloured versions), they were probably handed out for free.

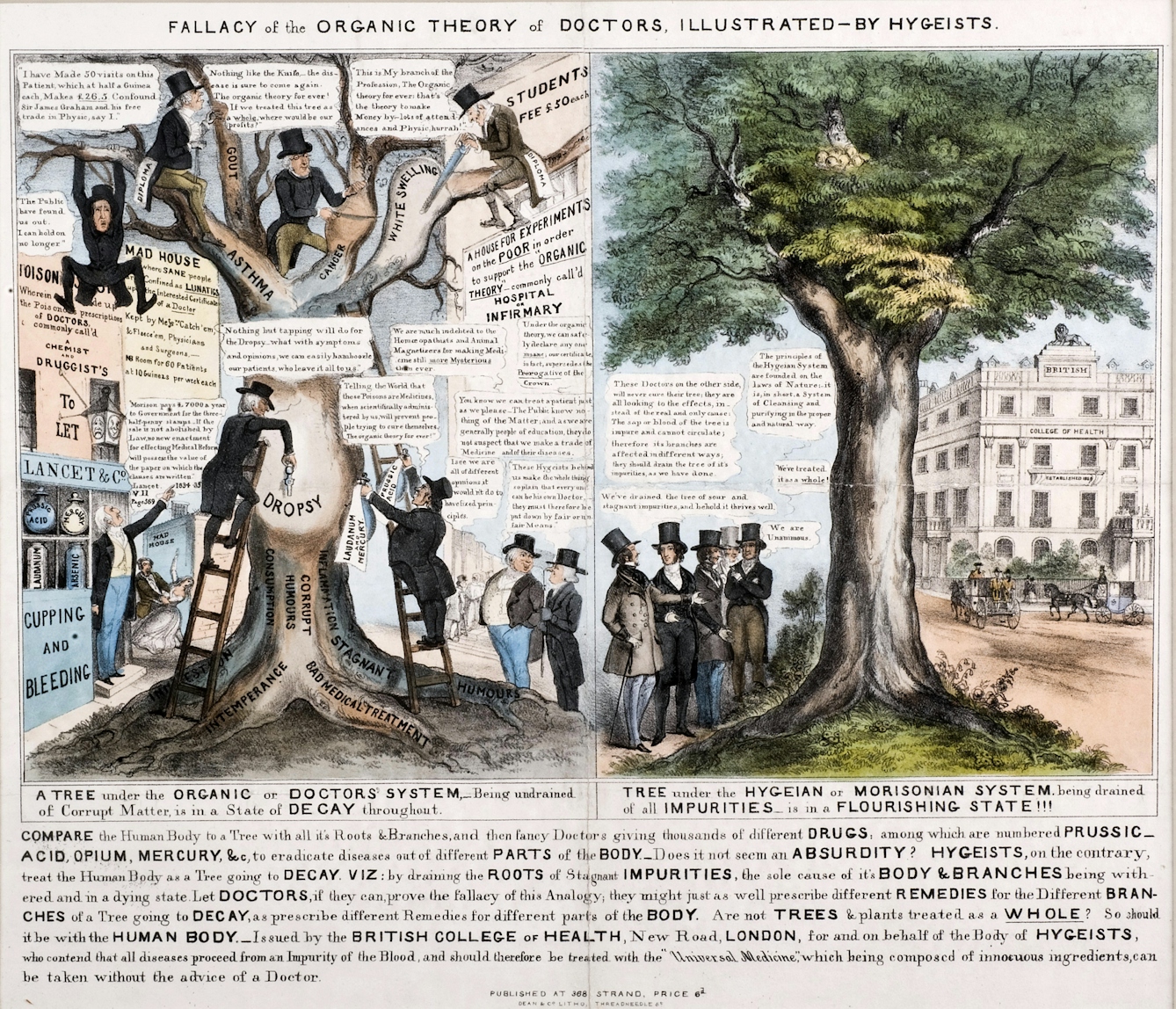

‘Fallacy of the Organic Theory of Doctors’ – part of Morison’s campaign against the medical establishment – features the British College of Health on the right.

Advertising through as many channels as possible, he started in 1825 with seven pamphlets, moving on to books, journals, brochures, almanacs, broadsides and posters. In 1834, the ‘London Medical Gazette’ claimed: “We can scarcely go into any street in London in which we do not see ‘Morison’s Universal Pills for the cure of every disease’ staring at us in large letters in the windows of one or more shops.”

‘Morality of Modern Medicine-Mongers’ – another of Morison’s anti-doctor publications.

A set of eight prints, probably issued by James Morison

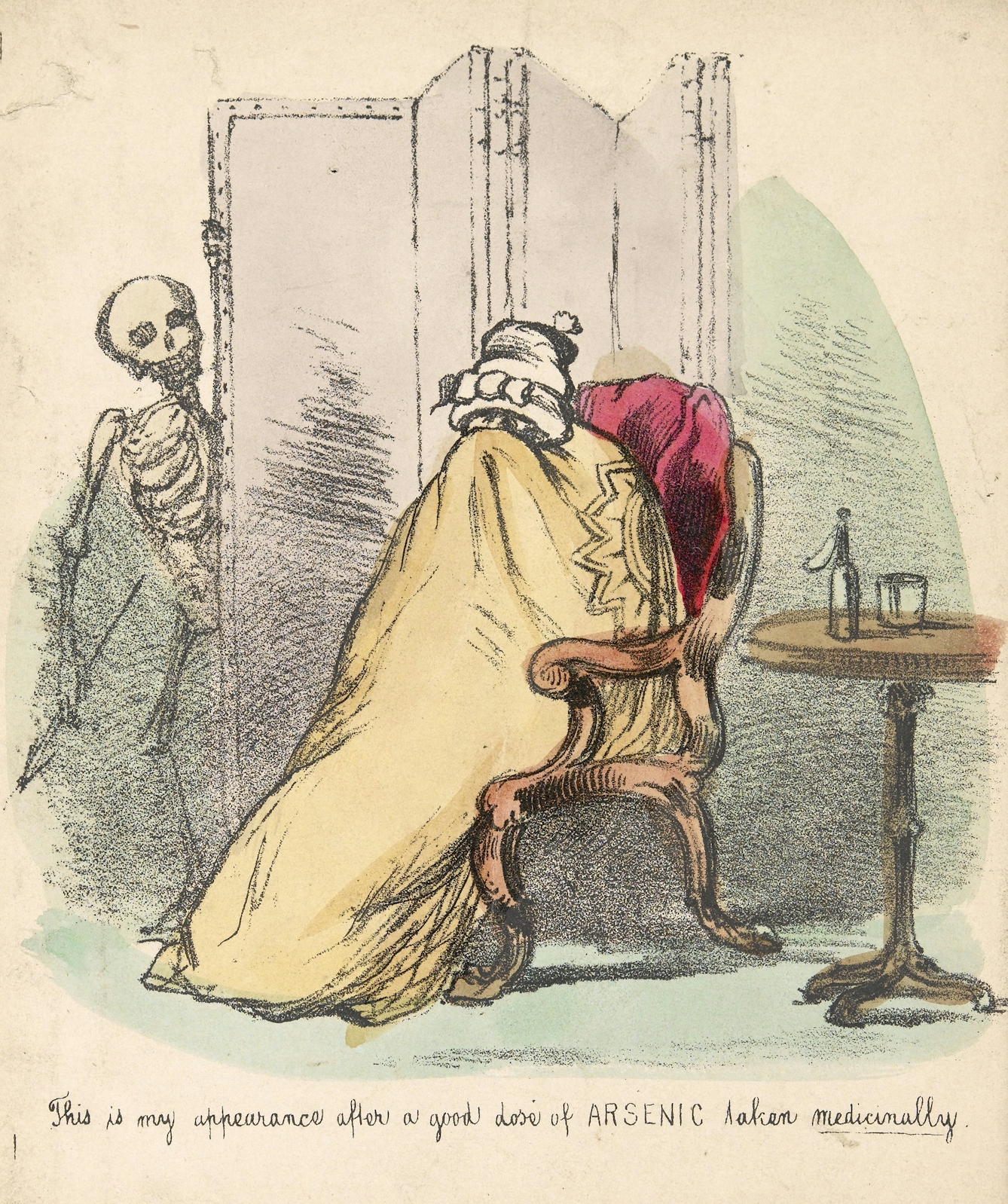

This is my appearance after a good dose of arsenic taken medicinally.

This is the appearance I presented when I became a convert to the homeopathic theory...

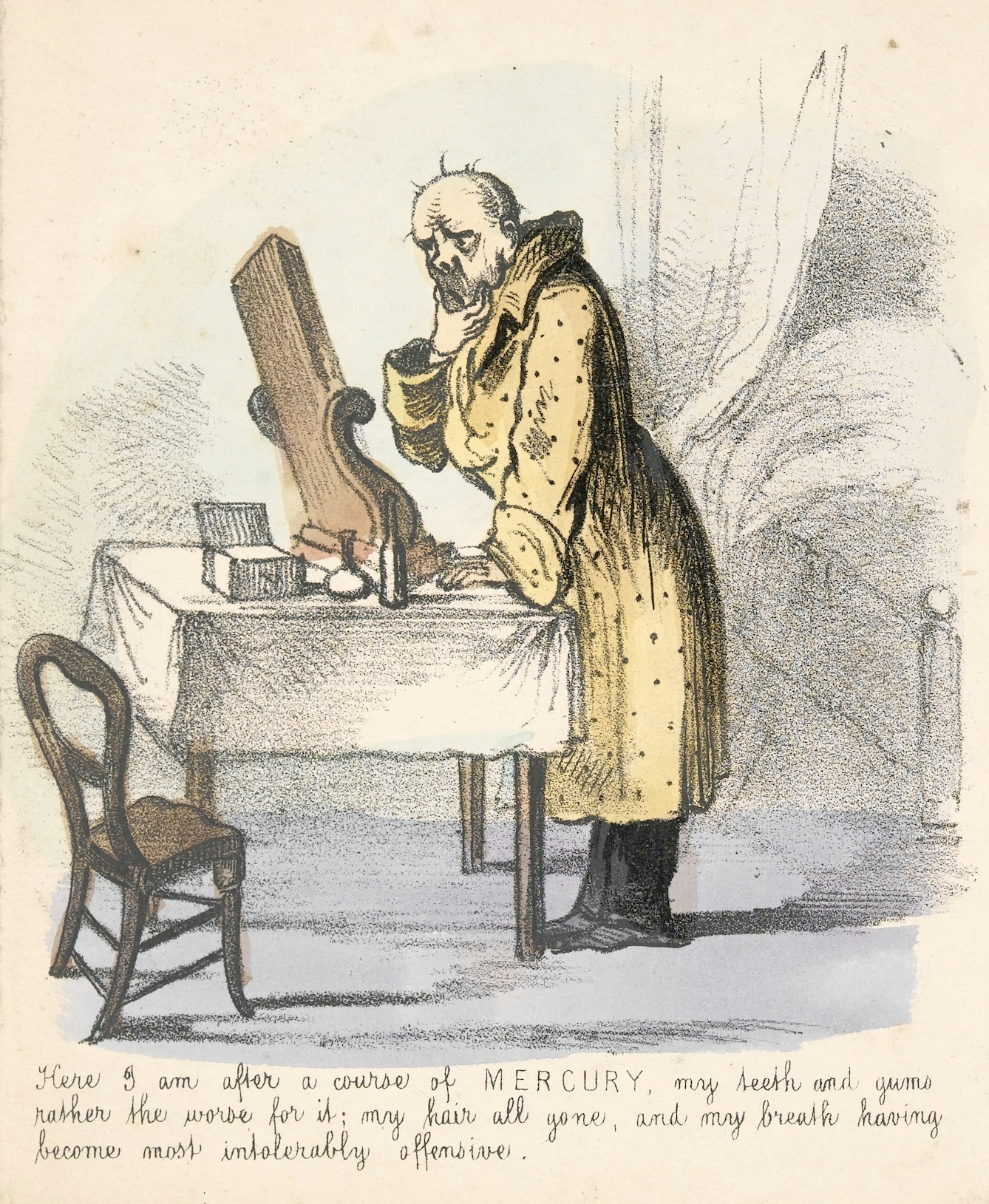

Here I am after a course of mercury...

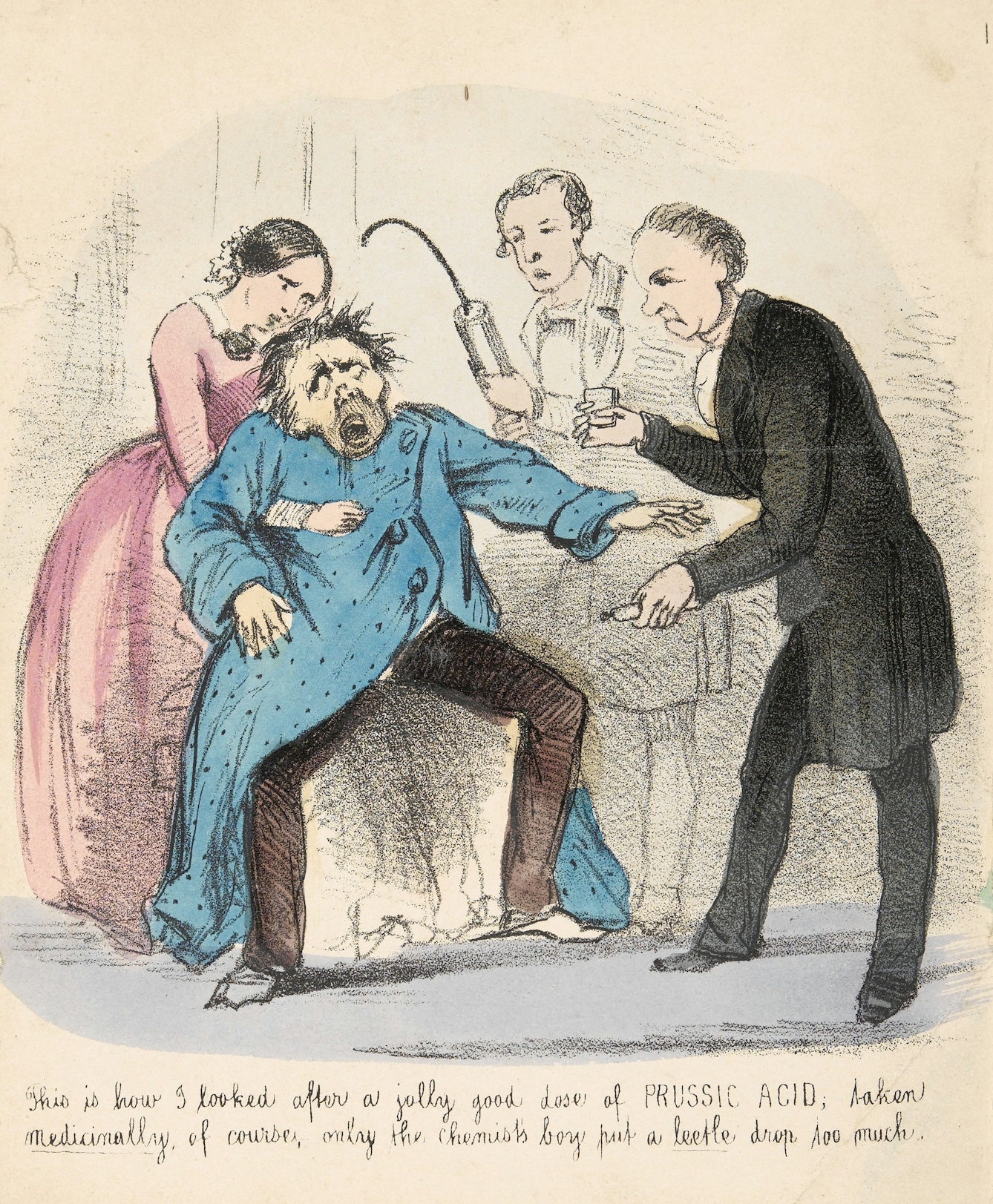

This is how I looked after a jolly good dose of prussic acid...

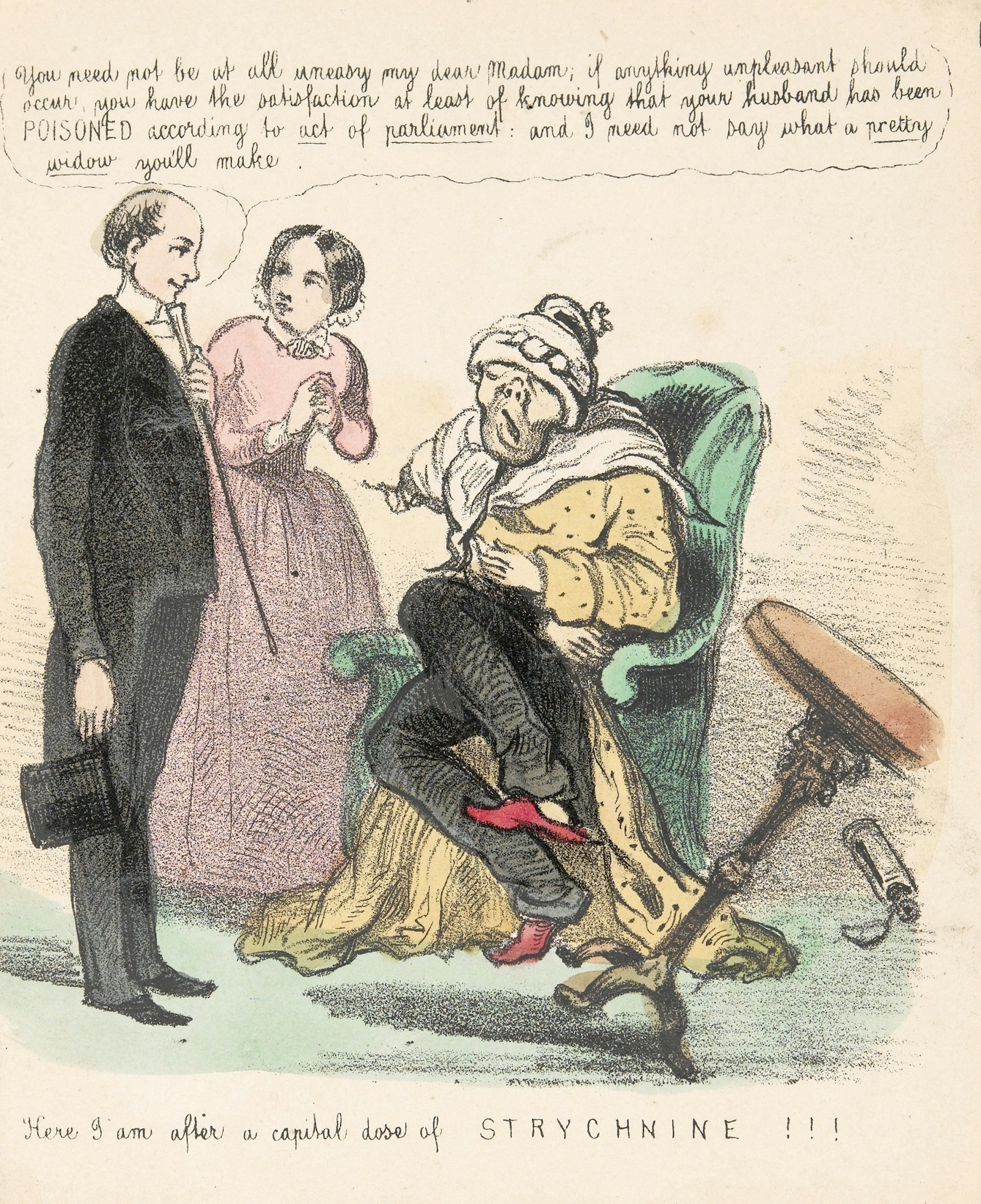

Here I am after a capital dose of strychnine!!!

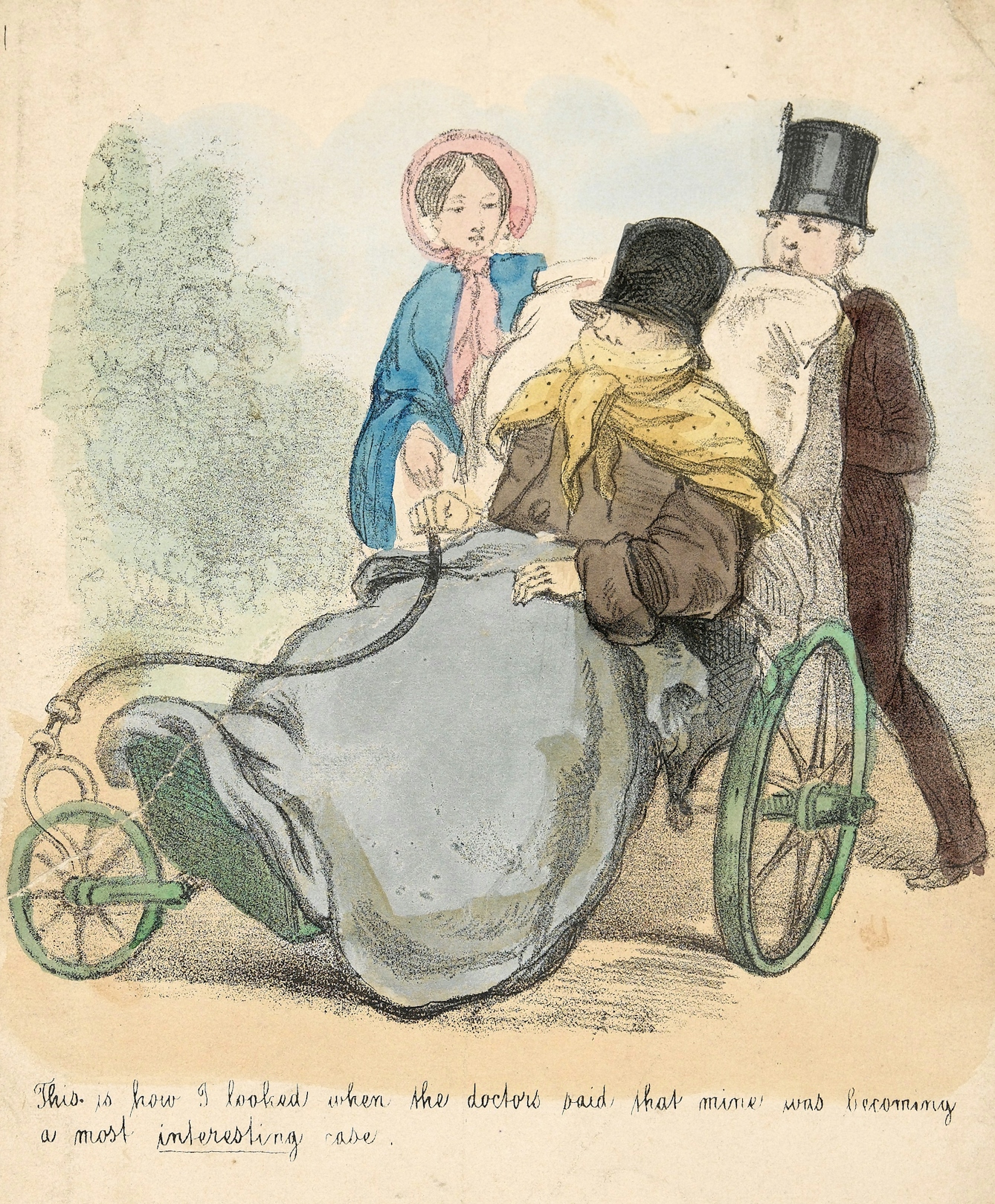

This is how I looked when the doctors said that mine was becoming a most interesting case.

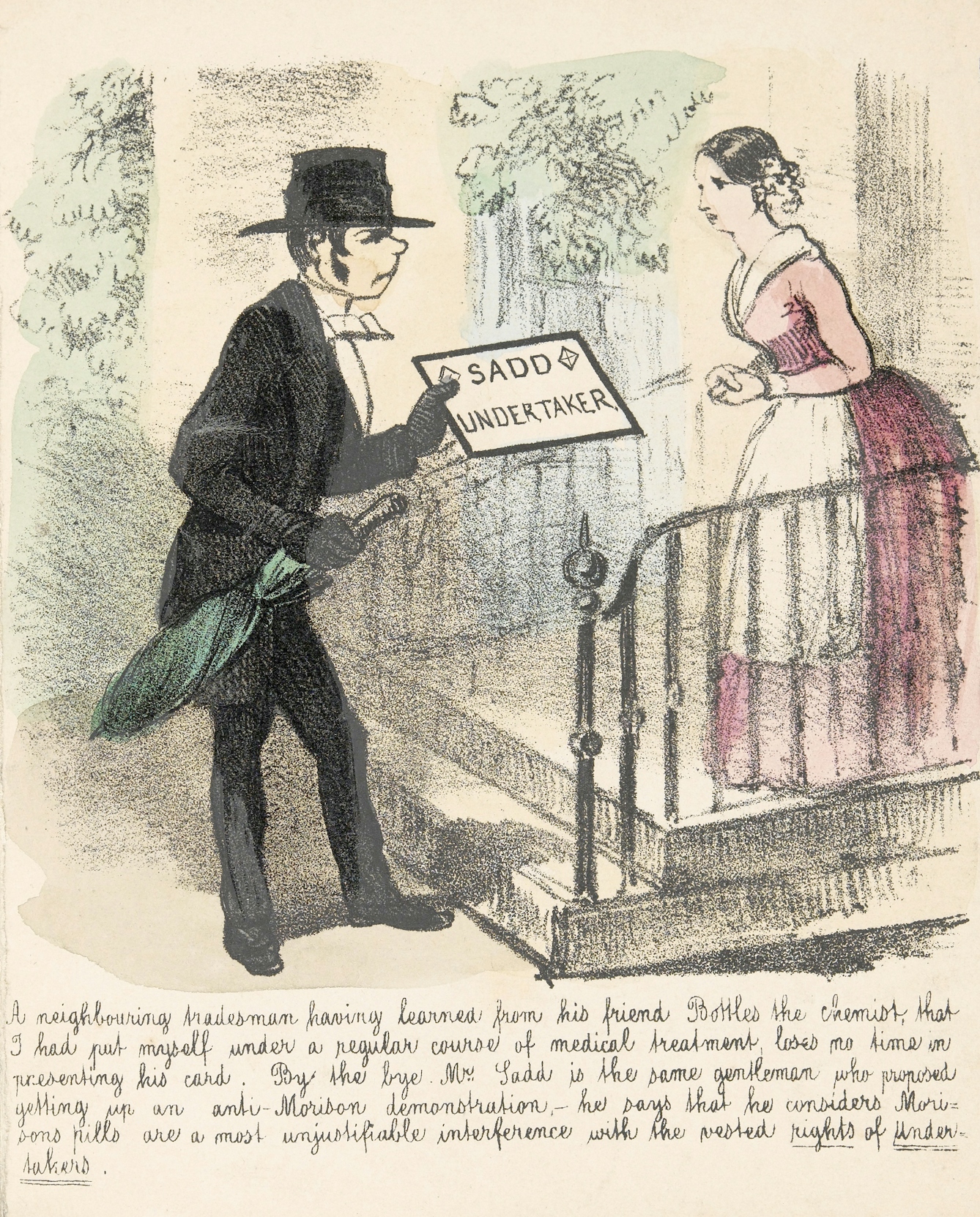

The undertaker calls upon hearing that I had put myself under a regular course of medical treatment...

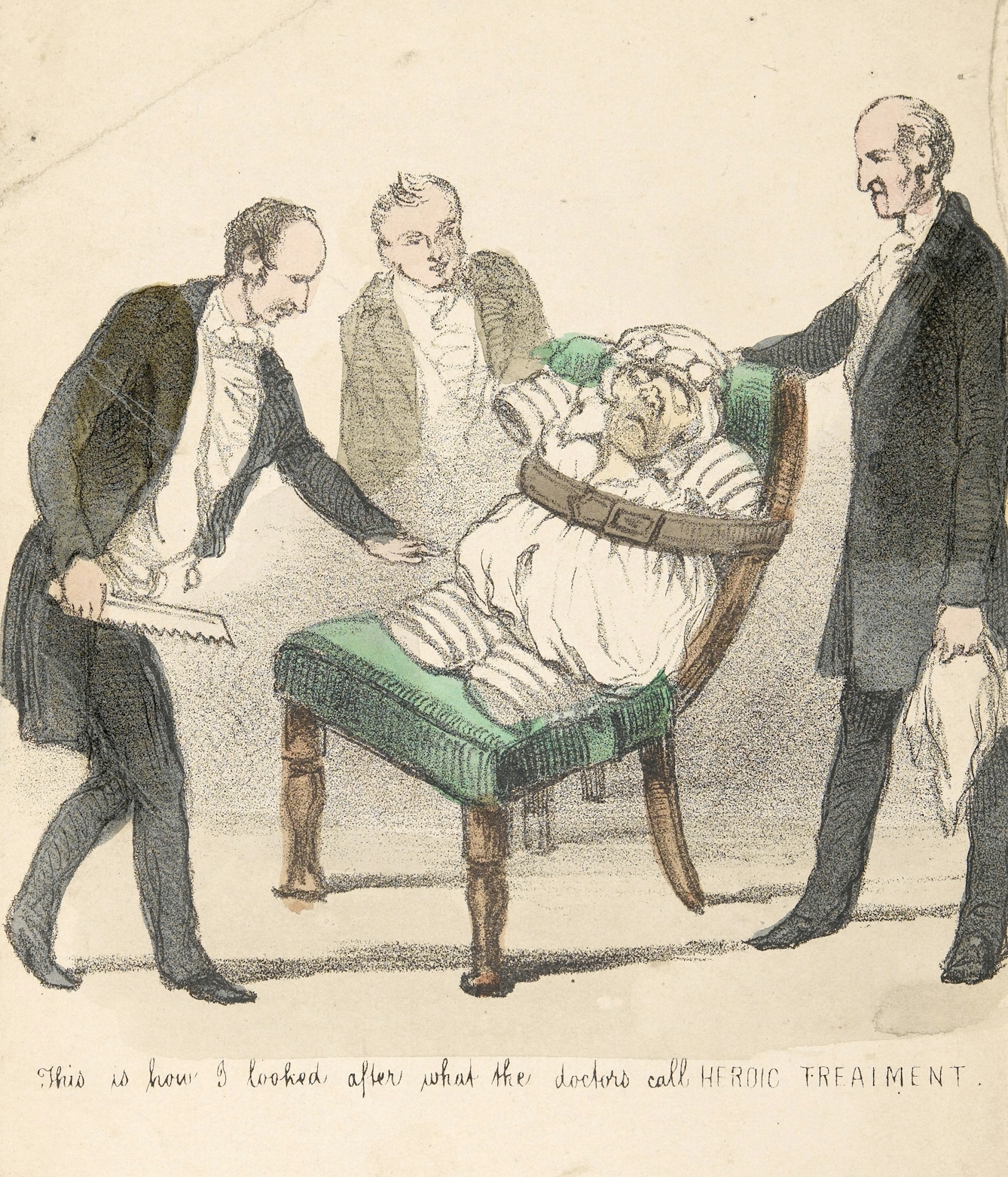

This is how I looked after what the doctors call heroic treatment.

But Morison’s pills could be just as dangerous as the arsenic, strychnine and mercury found in conventional cures. Although their formulation remained secret until the early 20th century, the pills were laxatives and could be fatal if taken in the large quantities often recommended. In 1836, John MacKenzie, aged 32, was administered 1,000 pills over 20 days by one of Morison’s agents, and died. In 1837, 12 deaths caused by excessive doses of Morison’s pills were investigated in York. One witness testified to taking 20,000 pills over a two-year period. Cases against Morison continued until 1839, but he escaped punishment as his agents bore the brunt of the accusations.

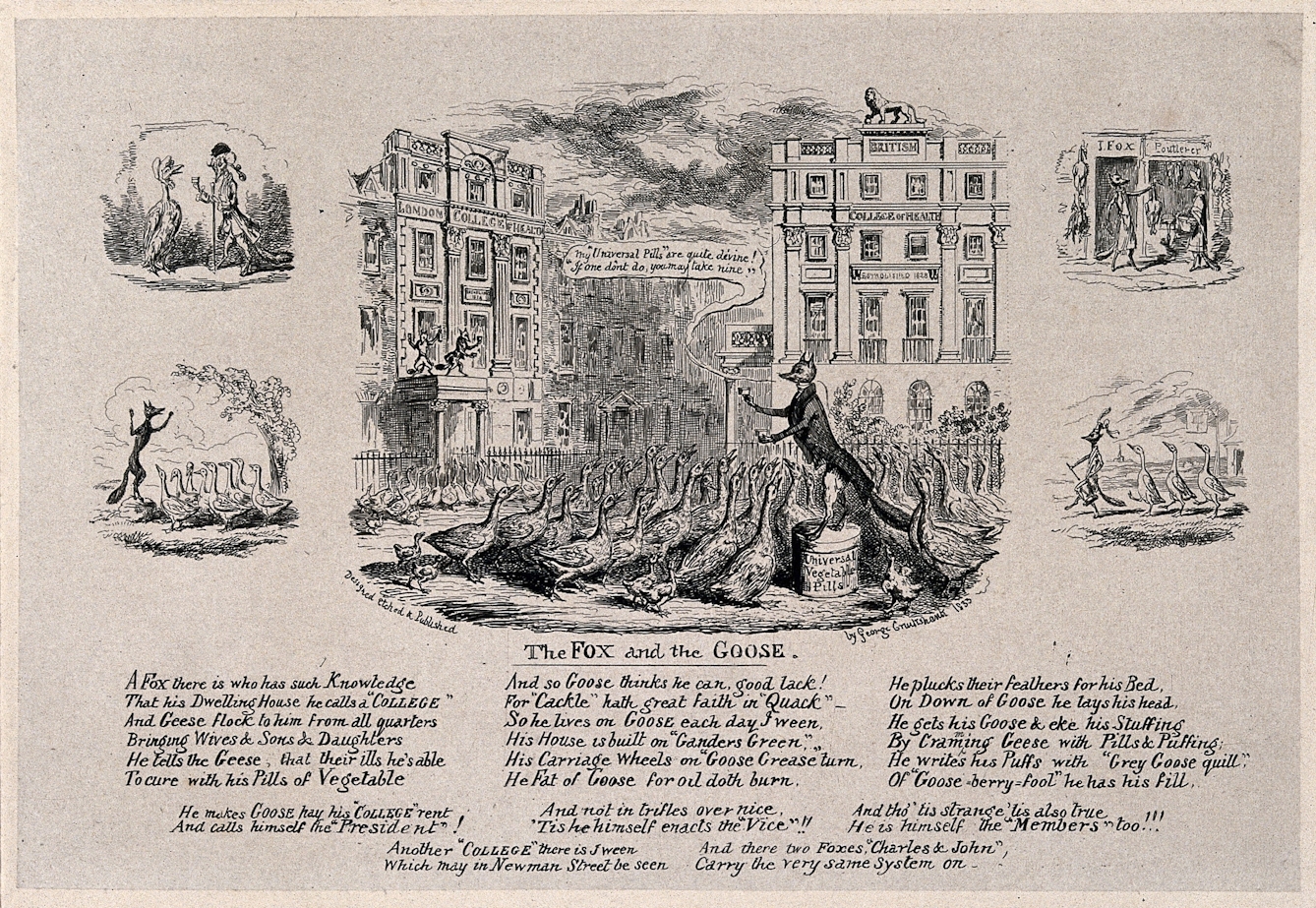

Thomas Wakley, editor of the medical journal ‘The Lancet’, was a leading opponent of Morison, attacking him as “the man-slaughterer”, the most visible representative of secret remedies and quackery. The vegetable pills also lent themselves to visual ridicule, being derided in around 25 caricatures produced from the 1830s. Noted caricaturist George Cruikshank was one of the artists to set Morison in his sights.

‘The Fox and the Goose’ by George Cruikshank.

Morison died in 1840 and his sons took over his very successful business. They expanded the product range, and sales remained high into the 1860s. Using data from medical tax stamps, pharmacy historian William Helfand has calculated that over a billion of Morison’s pills were sold between 1825 and 1849. They continued to be sold in Britain until the 1920s.

Caricatures of Morison’s advertising

Morison’s pills were visually ridiculed in caricatures, as were the enormous doses some people took. Here, a man has ballooned in size after taking ‘only’ 480 boxes.

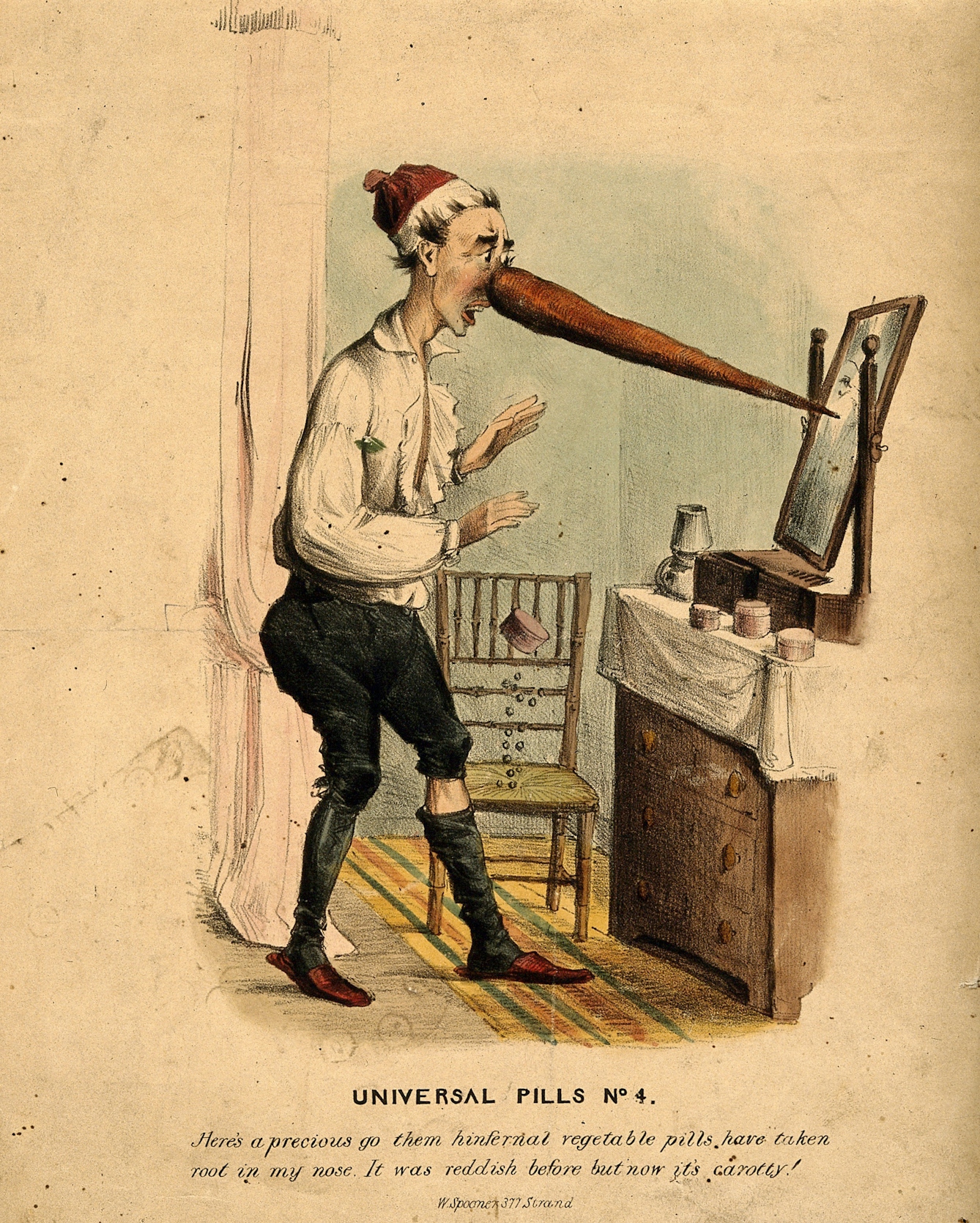

Many caricatures mocked the vegetable basis of the pills. This man has grown a carrot in place of his nose.

This image satirises the ‘cure-all’ claims of vegetable pills by depicting a tramp whose amputated legs grew back after a dose.

This patient is shown to have sprouted vegetable offshoots after taking 132 boxes of vegetable pills. The caption is full of vegetable puns.

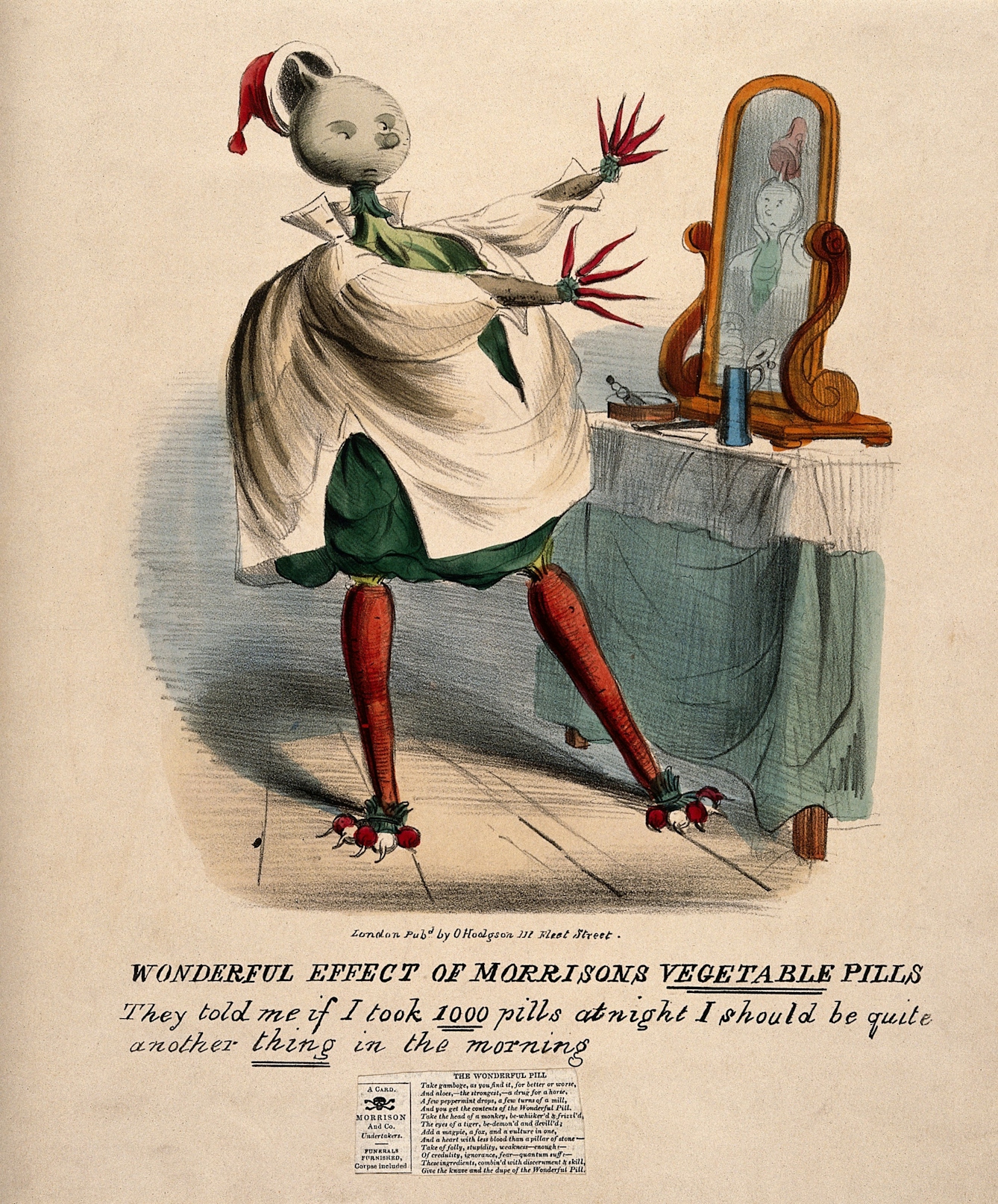

A person has entirely turned into vegetables after taking 1,000 pills, becoming “quite another thing”, as promised by advertisements.

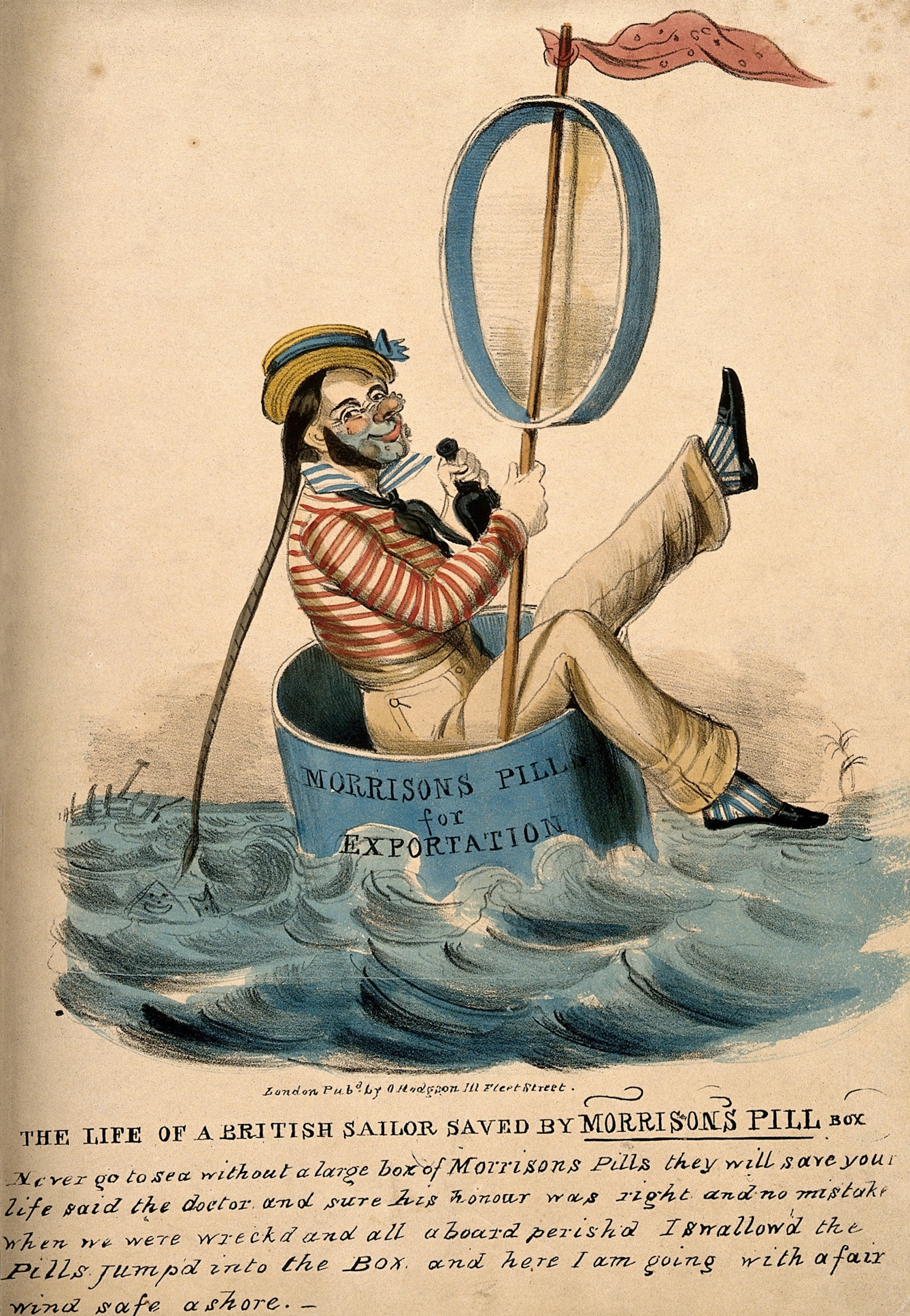

The overblown claim that the pills would save sailors’ lives is mocked in this caricature, which shows a pill tin being used as a raft.

The vegetable content of the pills is ridiculed by showing a patient appalled to find that he has sprouted grass from his face.

The emerging pharmaceutical profession battled to establish a respectable name for pharmacy against a backdrop of criticism about quack medicines. Pharmacists were satirised through popular prints, and their professionalism, ethics and credentials were questioned. A Parliamentary Select Committee in 1844 described the druggist’s shop as “vying with the gin palace in its tempting decorations”.

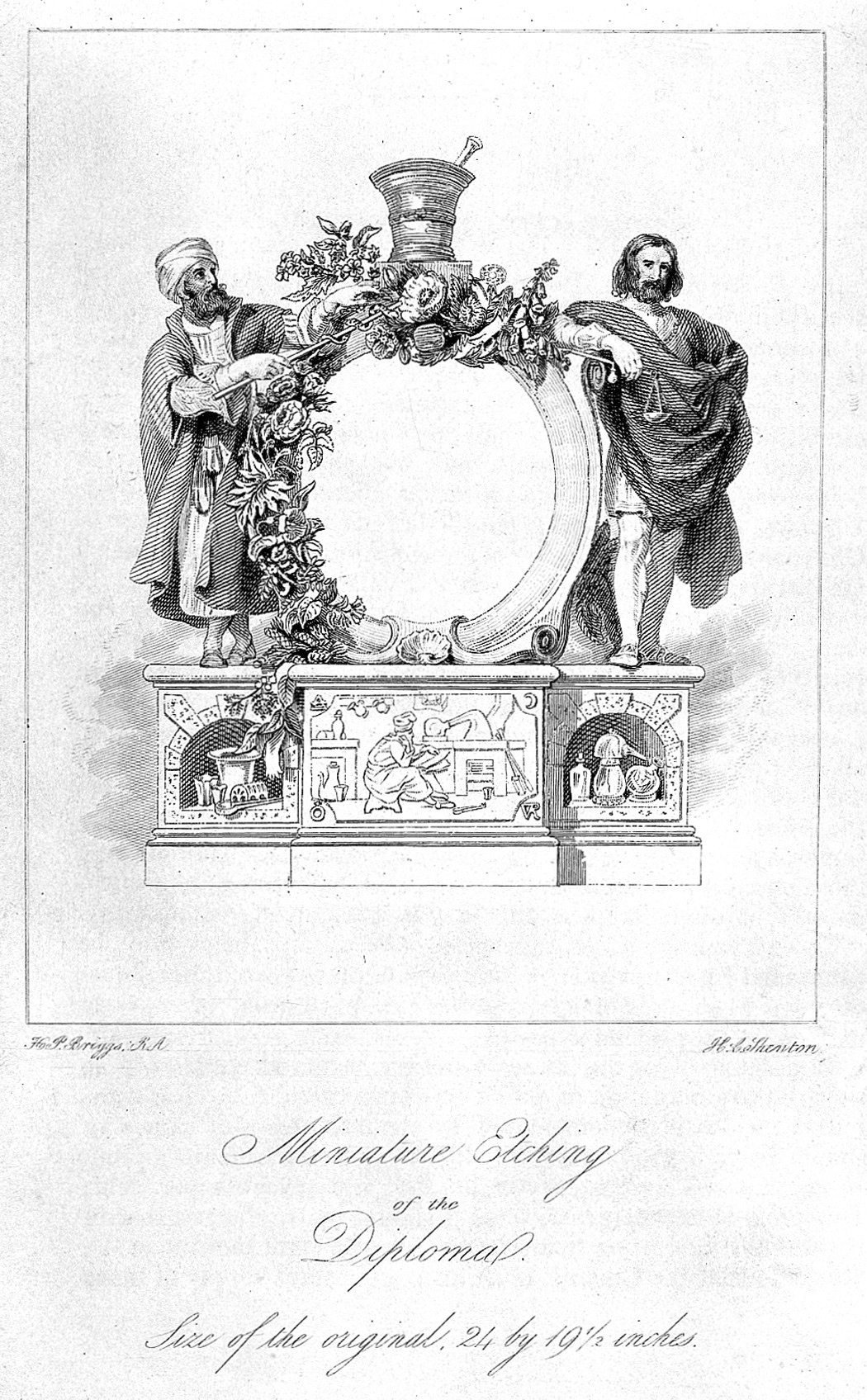

A draft diploma produced by the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

Signs of authority

As a newcomer to the medical establishment in 1841, the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain wanted to stress its strong foundations and the competence and reliability of its members. Along with a stringent scheme for education and examinations, its 1841 diploma design was used widely to convey authority, appearing on exam certificates, ‘The Pharmaceutical Journal’ and as the basis of its coat of arms, granted in 1844.

The coat of arms was adapted into a logo in the 1980s.

The society may have been new, but the coat of arms went to every effort to stress the ancient roots of the profession. The central shield is supported by two medical giants: Avicenna is shown using the Staff of Asclepius to point at a wreath of medicinal plants, while Galen holds a hand balance. The central medallion and figures stand on a pedestal showing an alchemist in a laboratory flanked by chemical and pharmaceutical equipment. A pestle and mortar sit atop the whole design. The traditional figures, medicinal plants such as foxglove, poppy and senna, and an alchemist at work reflect pharmacy’s long history.

The logo of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

In spite of more recent proposals to move away from this 1840s design, the society today still maintains a simplified version of the original coat of arms as its logo, featuring the dove of peace, aloe to represent plant-based medicine, a snake-entwined staff, and distillation apparatus, surmounted by a pestle and mortar, with a balance at the centre. Its historical foundations remain important even in the scientific age.

With the internet, the battle against quackery has moved to the virtual arena. British and European online pharmacies display an official logo to demonstrate their legitimacy, as design continues to play a part in establishing authority and reliability.