For Why Music? The Key to Memory, a partnership with BBC Radio 3, we’re exploring what four objects from our collection can tell us about how we remember. Take a look as Danny Rees tells Georgia Mann why a series of self-portraits by William Utermohlen holds a key to memory.

Listen

Georgia Mann and Danny Rees

It gives you a sense that he was exploring how he was feeling, his emotions, which is obviously what self-portraiture is all about... There's a lot going on that's perhaps hard to articulate any other way.

Take a look

When 61-year-old American artist William Utermohlen was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 1995, he embarked on a series of self-portraits to help understand what was happening to his mind. You can scroll through five of his paintings below, and you'll also find them on display in our Reading Room.

In pictures

'Figure in Studio with Mug' was one of the first self-portraits William Utermohlen produced after his diagnosis in 1995.

Utermohlen's paintings illustrate the development of his condition, providing a unique artistic and medical record of life with dementia. He created 'In the Studio (Self-Portrait)' in 1996.

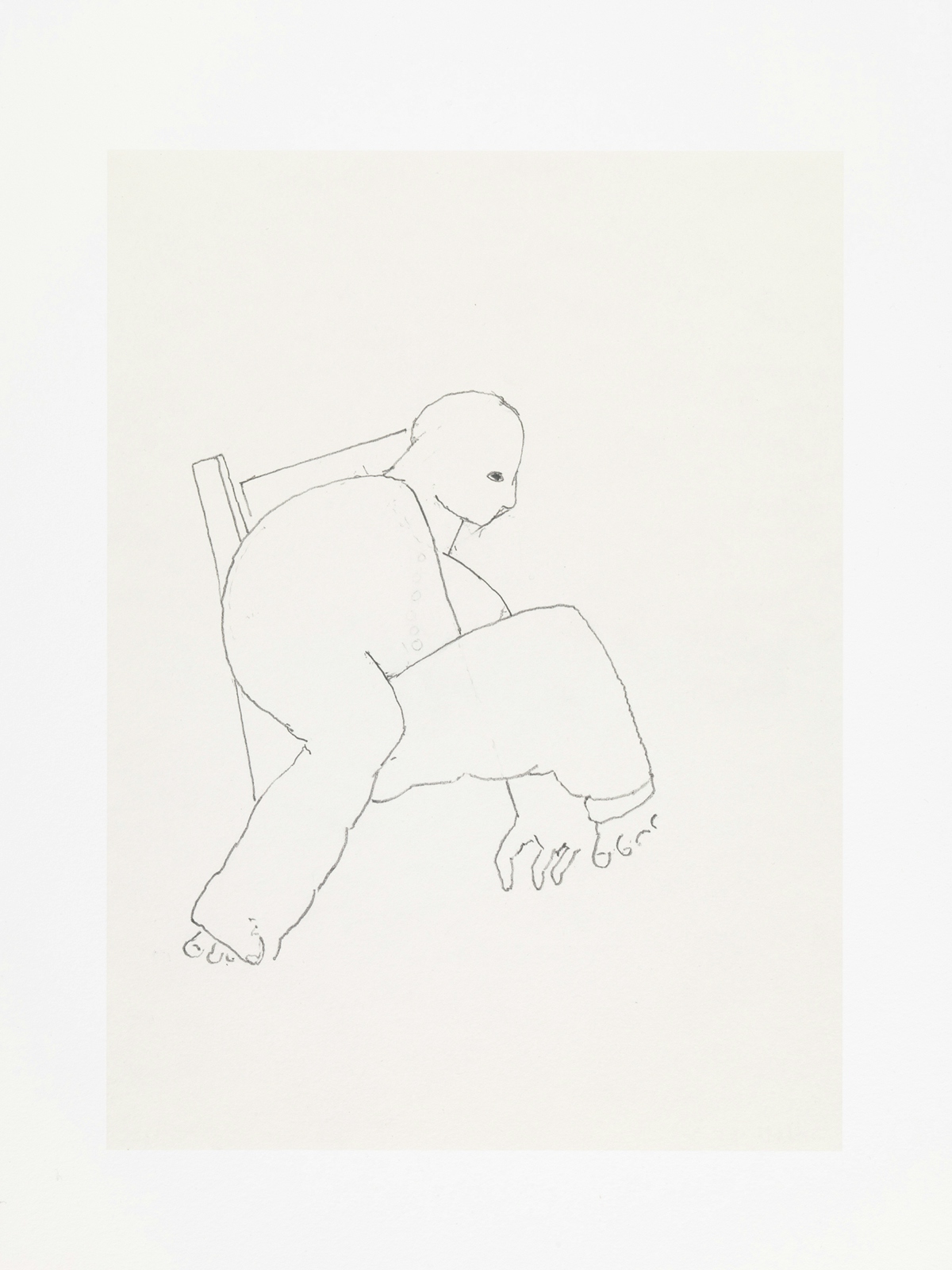

Utermohlen's paintings are influenced by his deteriorating motor control, changes in his spatial perception, and the artist's response to his condition. 'Twisted Figure in Chair' also dates from 1996.

William Utermohlen began 'Self-Portrait with Saw' after agreeing to donate his brain to science after his death.

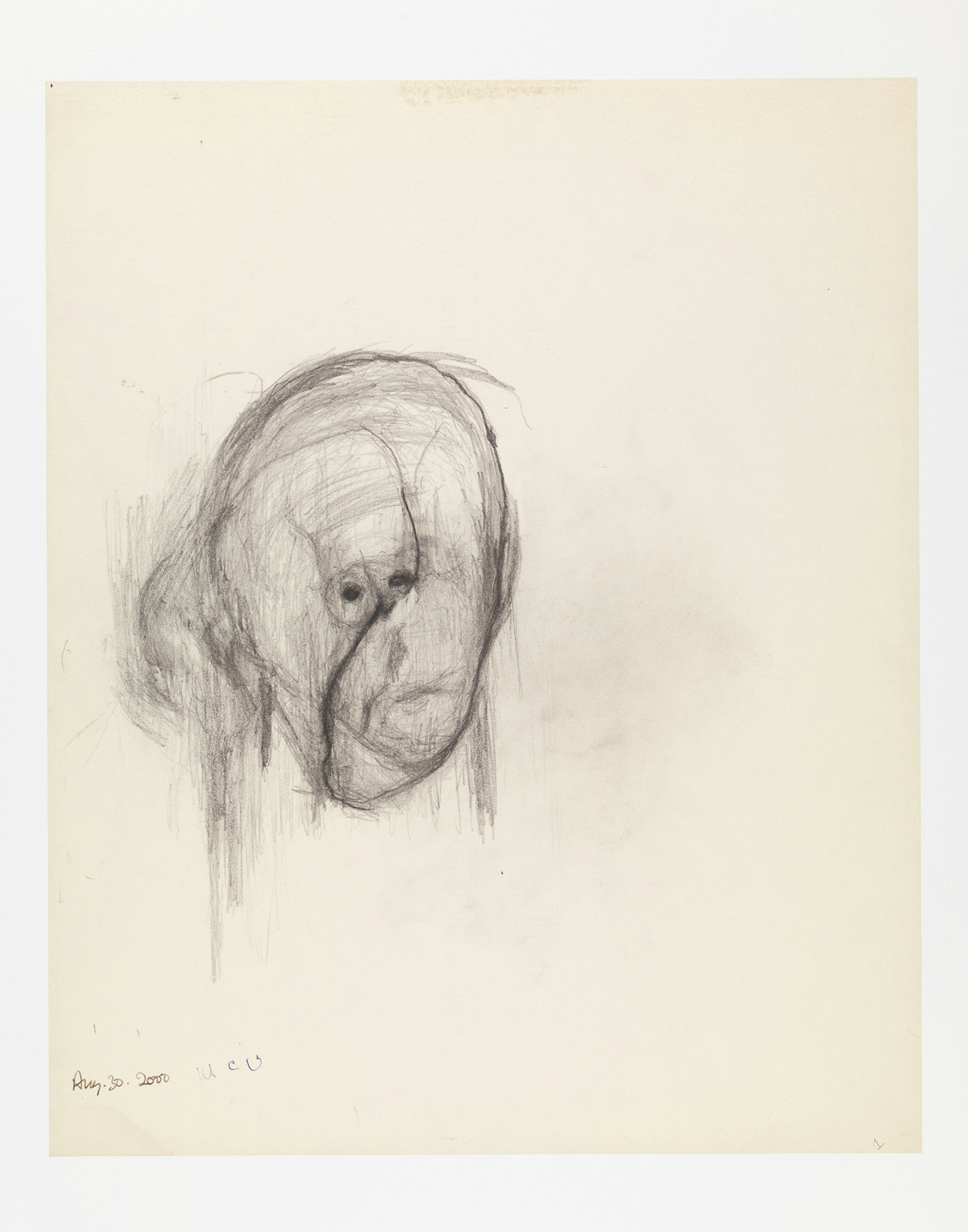

'Head 1' is the last work William Utermohlen produced before his death in 2007.

Audio produced by Freya Hellier in collaboration with BBC Radio 3. Why Music? The Key to Memory takes places from 13-15 October 2017.

Science writer Philip Ball's article, How music opens the doors of memory and the mind explores the relationship people living with dementia can have with music, and what this reveals about how memories are formed.

Full audio transcript

Georgia Mann: So I’m here in the Reading Room at Wellcome Collection with Danny Rees, an Engagement Officer here, and we’re looking at some self portraits. Danny, what is this?

Danny Rees: So we’ve got a series of five self-portraits and the first one is made in the year 1995, so this is the date that William Utermohlen who is the artist, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. So we’re seeing different stages of an artist living with Alzheimer’s in the five portraits that go up until 2000 when he made his last drawings.

[music]

Georgia Mann: Danny, just looking at this first in the series, 'Figure in Studio with Mug', it’s maybe to be expected, a very disorientating image I find. It’s a sketch, there’s a blurring of facial features. Even though the artist is holding a mug, the mug isn’t quite touching his fingers, everything’s floating almost.

Danny Rees: Yes, it’s interesting, I think although this is quite an early work, you’re already getting a sense of anxiety. It gives you a sense that he was kind of up and down and exploring how he was feeling, his emotions. Which is obviously what self portraiture is really all about.

[music]

Georgia Mann: I’m interested in this here -1997 - so we’re now two years down the line from the Alzheimer’s diagnosis. His eyes look sort of unfocused, and then there’s this thing looming in the corner. What is that?

Danny Rees: This is quite an old-fashioned looking saw. It’s very deliberately put there because, as you see on the label, it mentions he began this on the day he willed his brain to science. This is something that really played on his mind quite a lot.

[music]

Georgia Mann: It’s easy at surface value to think that you might be reading a decline in these self-portraits but in actual fact there’s something wonderfully reassuring about what we’re looking at here because he’s still creating things that have such impact and speak so strongly.

Danny Rees: He keeps going much longer, I think, than was expected and he’s able as well to be more aware of his condition. Not only is he able to show his characteristics - because this is a very good likeness of how he’s looking - but it really conveys the feeling in his eyes there, they’re so expressive about that kind of anxious feeling. There’s a lot going on there that is perhaps really hard to articulate any other way.

[music]

Georgia Mann: The final work in this series is, for me the most affecting, there is just something so sad, and almost horrifying about this to me. We’re back to it being a pencil sketch, the lower portion of William Utermohlen’s face. No eyes, we get a nose, we get a bit of an outline of a mouth and I think an ear, but they’re all sort of, again, this sense of slipping, it’s almost as if he’s begun sketching it, started again…

Danny Rees: It is quite chilling I suppose, in a way, because here is an artist, a self-portrait, and there are no eyes which is really quite disturbing to look at. Having said that, there’s still a lot of artistry there, this really is in latter stages of dementia. There’s like a core there of something that somebody knows and something that someone is still trying to do, and is still doing it in a very effective way. I think it’s still a remarkable portrait really.

[music]