The illustrations in medieval herbals are beautiful and mysterious. But if you know how to read them, they also convey a wealth of knowledge about the plants they portray.

Plant portraits

Words and poetry by Julia Nurseaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

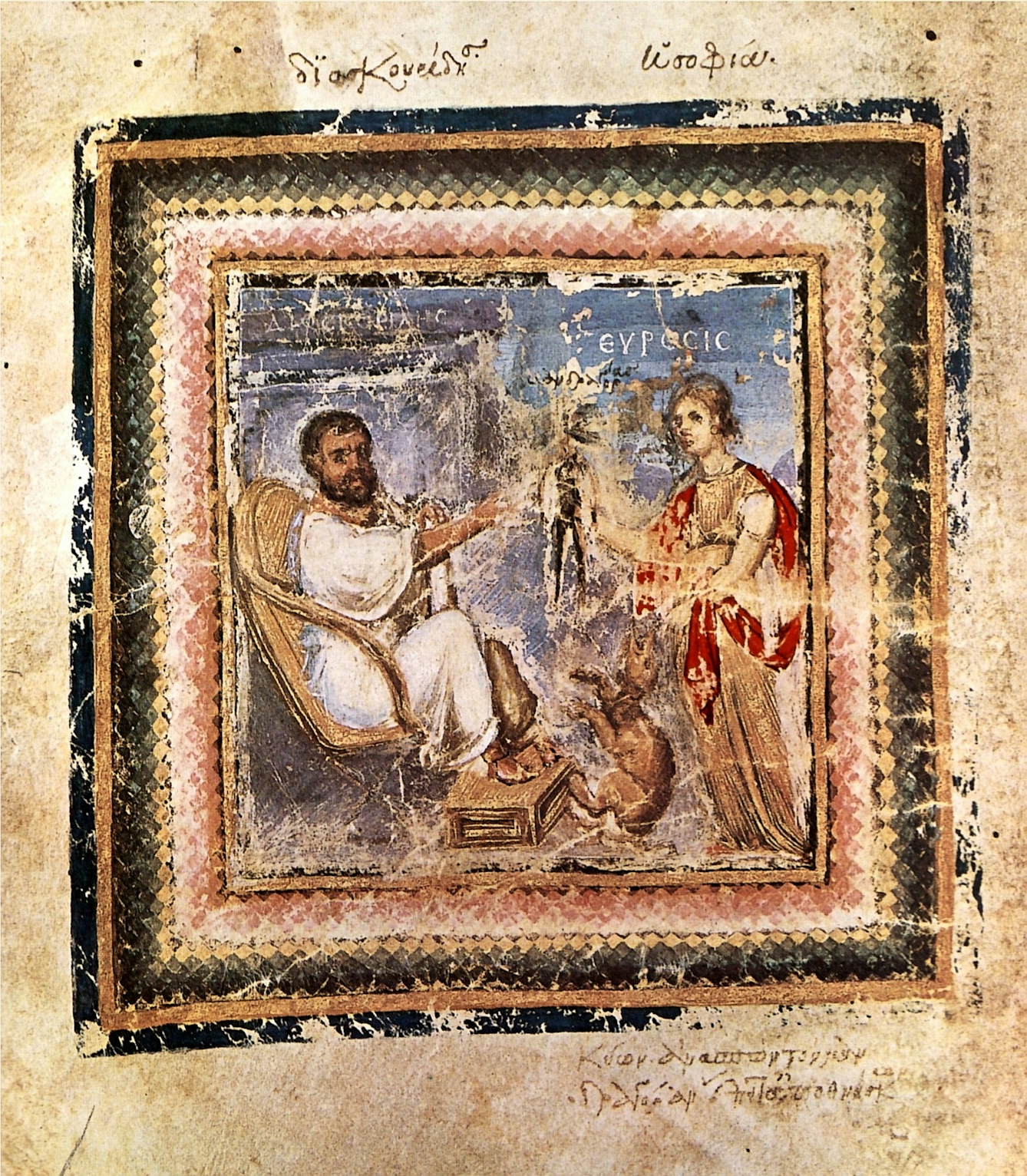

The illustrated herbal has an almost unbroken line of descent from the ancient Greeks to the Middle Ages. The tradition owes much to a work by the Greek physician Dioscorides called ‘De Materia Medica’ (50–70 CE), which describes around 1,000 medicines, largely derived from plants, along with some animals and mineral substances.

Physician preparing an elixir. From an Islamic version of ‘De Materia Medica’ (1224 CE).

‘De Materia Medica’ was circulated throughout the European and Islamic worlds. During that time it was translated, embellished and added to in commentaries and copies for local use. In Europe, this tradition developed into the medieval herbal, created in monasteries, usually by Benedictine monks, who ran hospitals and dispensaries with herb gardens.

Collecting plants in a monastic garden, from ‘Kreuterbuch, von natürlichem Nutz, und gründtlichem Gebrauch der Kreutter’, 1550.

Wood-block printing increased the use of images in herbals. This block of Artemisia maritima was used in Pietro Mattioli’s popular 1568 translation of Dioscorides’s original work. The images would have been printed before the text could be laid.

Following Dioscorides, medieval herbals provided more than just information about the medical use of plants. A typical entry might contain synonyms for the plant and details of its characteristics, distribution and habitat. As well as existing knowledge and lore about the plant, there might be instructions on how it should be gathered and prepared, and recipes for cures.

Pages from a 15th-century herbal, 1480–1500, translated from a 12th-century Latin manuscript by Matthaeus Platearius (d. 1161).

For nearly a thousand years the same patterns of illustration were copied from one manuscript to another with little alteration. The original illustrations were created primarily for identification in nature. As with all natural illustration, the artists were faced with the challenge of depicting a recognisable image of the plant while also including all its different parts, large and small. The images needed to both record and instruct. Some of the images also served a decorative purpose, capturing the general essence of the plant with or without botanical accuracy. In ‘Medieval Herbals’ (2000), Minta Collins refers to these as “plant portraits”.

The mandrake root

Perhaps no plant illustrates the evolution of the plant portrait in herbals more than the mandrake.

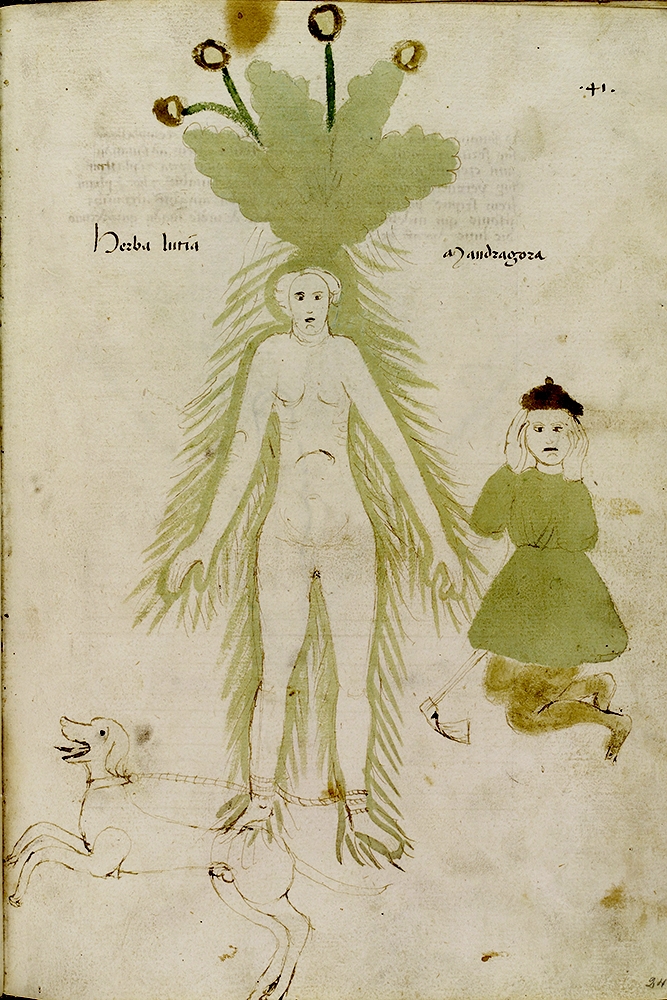

According to the medical doctrine of signatures, there was a clue to the medicinal use of a plant in its similarity to a body part or organ – if there was a likeness, it was meant to treat that part of the body. In medieval herbals the mandrake is consistently depicted as a human form, so powerful that the scream of the living root when wrenched from the ground was believed to be deadly to humans. The recommended method of extraction is often represented as a dog pulling the root from the ground while the plant gatherer stands at a safe distance.

Mandrake was believed to exercise almost magical control over the body. No wonder then that the form of a whole human could be discerned in its roots. It was recognised as an anaesthetic from Roman times. Mandrake was also said to improve fertility and act as an aphrodisiac, so both male and female forms were identified in herbals.

Even if the Benedictine monks did not believe the mythology around the plant, it’s a testament to the copying tradition that this plant portrait persisted for hundreds of years.

The magical mandrake

All the elements of the living mandrake root are present in this sixth-century image of Dioscorides receiving the root, including a dog in the foreground. From the ‘Juliana Anicia Codex’, a Byzantine Greek version of 'De Materia Medica' from 515 CE.

A dog pulling at the roots of a mandrake plant. From a herbal known as the ‘Pseudo-Apuleium’, 1250.

Female mandrake being uprooted by a dog; nearby a man kneels with his hands to his ears. 1475.

The ‘Hortus Sanitatis’, an early natural history encyclopaedia, also featured woodcuts of male and female mandrakes. Second edition 1491.

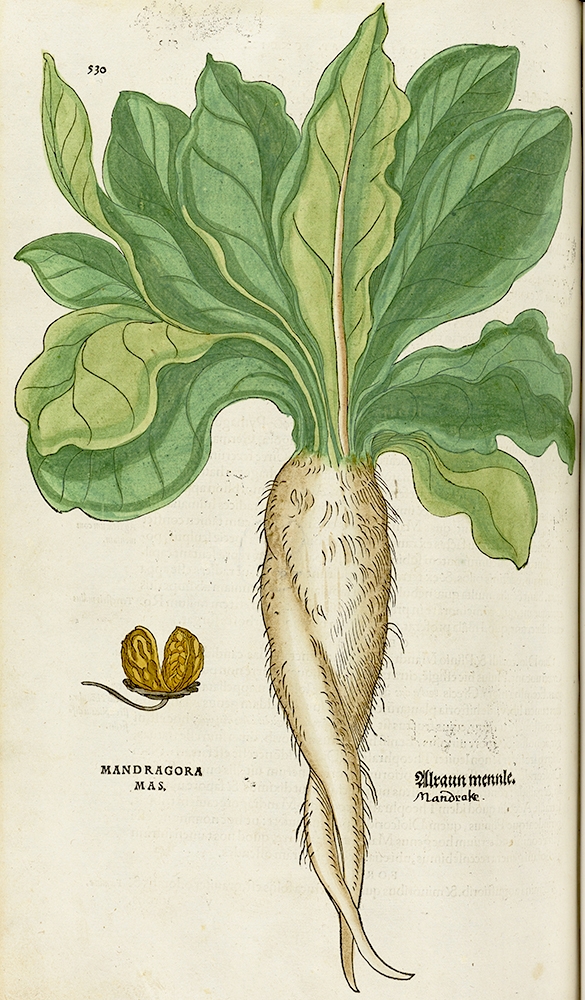

Leonhart Fuchs’s herbal ‘Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants’ first appeared in 1542 and became a Renaissance botanical bestseller, largely for its attractive full-page colour woodcuts such as the Mandragora.

John Gerard’s ‘Great Herball’ of 1597 was the first to pour scorn on the mandrake legend: “There have been many ridiculous tales brought up of this plant.” However, he couldn’t resist ‘humanising’ the roots and including male and female versions.

In this 1701 Illustration of a mandrake root by Abraham Bosse, the root is still being made to look female.

Botanical illustration of Mandragora officinarum (mandrake), 1817–27.

As the monastic tradition declined, many of the visual conventions of the medieval herbal were taken up in botanical illustrations for natural history guides and materia medica textbooks for pharmacists and botanists. In particular, depicting different parts of a plant simultaneously proved a useful technique for scientific illustration. In the case of the mandrake, even guides that disavowed in no uncertain terms the mythology around the plant found the plant portrait irresistible when illustrating it, right up to the 18th century.

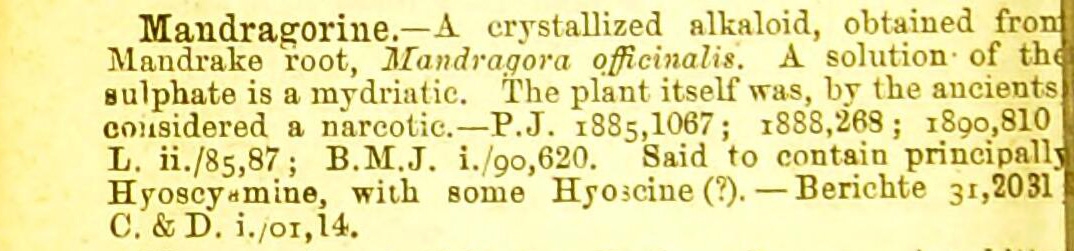

In the 19th century, the active chemical in mandrake was isolated and identified as one of a class of chemicals called alkaloids. Unlike the medieval monk, the chemist increasingly did not have to rely on the identification and preparation of his medicines from source. He only needed to identify the isolated chemical and know its uses and contraindications. Consequently, entries for mandrake in 19th-century pharmacopoeias are much diminished.

The entry for the active ingredient in Mandragora officianalis (mandrake) in ‘The Extra Pharmacopoeia’, 1901.

Signs and symbols

One thing that pharmacopoeias and herbals have in common is the use of symbols as a shorthand for generic properties. Look at a modern pharmacopoeia and you’ll still see hazard signs like the skull and crossbones for toxicity. Medieval herbals used images of scorpions, spiders and, in particular, snakes as symbols, but the meanings were often more complicated.

Plantain (Plantago lanceolata) was believed to be particularly good for venomous bites – of the scorpion, snake and spider. The plant was applied directly to the wound, or the juice of the plant could be drunk.

Nux vomica is just one of many plants that appears with a snake symbol in medieval herbals. Although used as a stimulant for centuries, the unprocessed seeds also induce severe vomiting – hence the name. In fact, the active ingredient in Nux vomica is the powerful alkaloid strychnine, which, once isolated in the 19th century, became the poison of choice for many a Victorian murderer.

Somewhat confusingly for the modern reader, a snake might also indicate that a plant offered relief from poisonous bites, or that it might be found near venomous beasts. For instance, in one particular herbal, chamomile is recommended with “a little wine” as protection from snake bite, and appears with a snake in the illustration.

Symbols in a 15th-century herbal

The Nux vomica (on the left) was used to cause vomiting and expel phlegm and bad bilious humour from the body – the presence of the snake symbolises its toxic properties. Neille, Nigella sativa (on the right), was also known as ‘devil in the bush’, among various other names.

One dram of Chamomilla (chamomile) with a little wine was recommended as protection against the poison from bites of venomous beasts and serpents.

Doctors were instructed to “reduce and curb” the “violence” of Dyagredium (scammony), which was administered to purge “bilious and melancholic humours”. It was not believed to be poisonous, but snakes were apparently attracted to it.

Serpentine (Dracunculus vulgaris) was also known as snake lily because its stem resembled a grass snake; allegedly “if anyone rubs himself with this plant, he is protected from all serpents”.

The virtue of costus (Saussurea lappa) lay in it its bitterness, and it was used primarily as a diuretic. Incense from its long roots was also used to treat the ‘belly worms’ depicted in this image.

The chief virtue of the Apolinaris (right) was to cure ulcers and the bites of earthworms. The plant was cooked with fat and “a goblet of wine”, then applied by plaster to the injury. The illustration includes an earthworm rather than a snake.

Birthwort (Aristolochia clematitis) was so called for its resemblance to the womb and birth canal, and was believed to help women in labour. In medieval herbals you’ll see the snake symbol beside it, perhaps because it contains a toxic acid. In 1991, dozens of women at a Belgian slimming clinic reportedly suffered kidney failure after using extracts of the plant.

Aristolongia longa (long-rooted birthwort) was used to fumigate under the beds of sick children to “make them merry”, and as an aromatic stimulant in rheumatism and gout and for removing obstructions, in particular after childbirth.

We may have lost some of the richness of the medieval herbal as a source of knowledge, but at least some of its traditions of classifying and decoding plant knowledge live on in modern botanical guides, safety datasheets and modern pharmacopoeias.

About the author

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. She currently runs the Exploring Research programme, and has a particular interest in the medieval and early modern periods, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.