Increasingly sophisticated virtual reality can reward almost every sense, creating a fiction that the brain believes is authentic. Stevyn Colgan explores the addictive possibilities of this sensory immersion, from calorie-free eating to victimless crimes.

Virtual reality and the fix of the future

Words by Stevyn Colganaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

We know that certain uses of the internet – such as gaming and viewing online pornography – can become addictive. The brain’s reward system, the release of dopamine, keeps the user coming back for their ‘fix’ and pushes them on to ever more explicit and graphic content in order to maintain the ‘high’. And, unlike drug users, gamers and porn addicts are able to keep dopamine levels stimulated for hours on end, as Norman Doidge explains in his 2008 book ‘The Brain That Changes Itself’.

In the case of chronic porn users, this state of continuous intoxication can lead to physical and psychological side-effects, including erectile dysfunction, lethargy, lack of motivation, social anxiety and emotional numbness. It can also lead to declining interest in a real partner. In every respect, it can be as damaging to the user as any drug addiction.

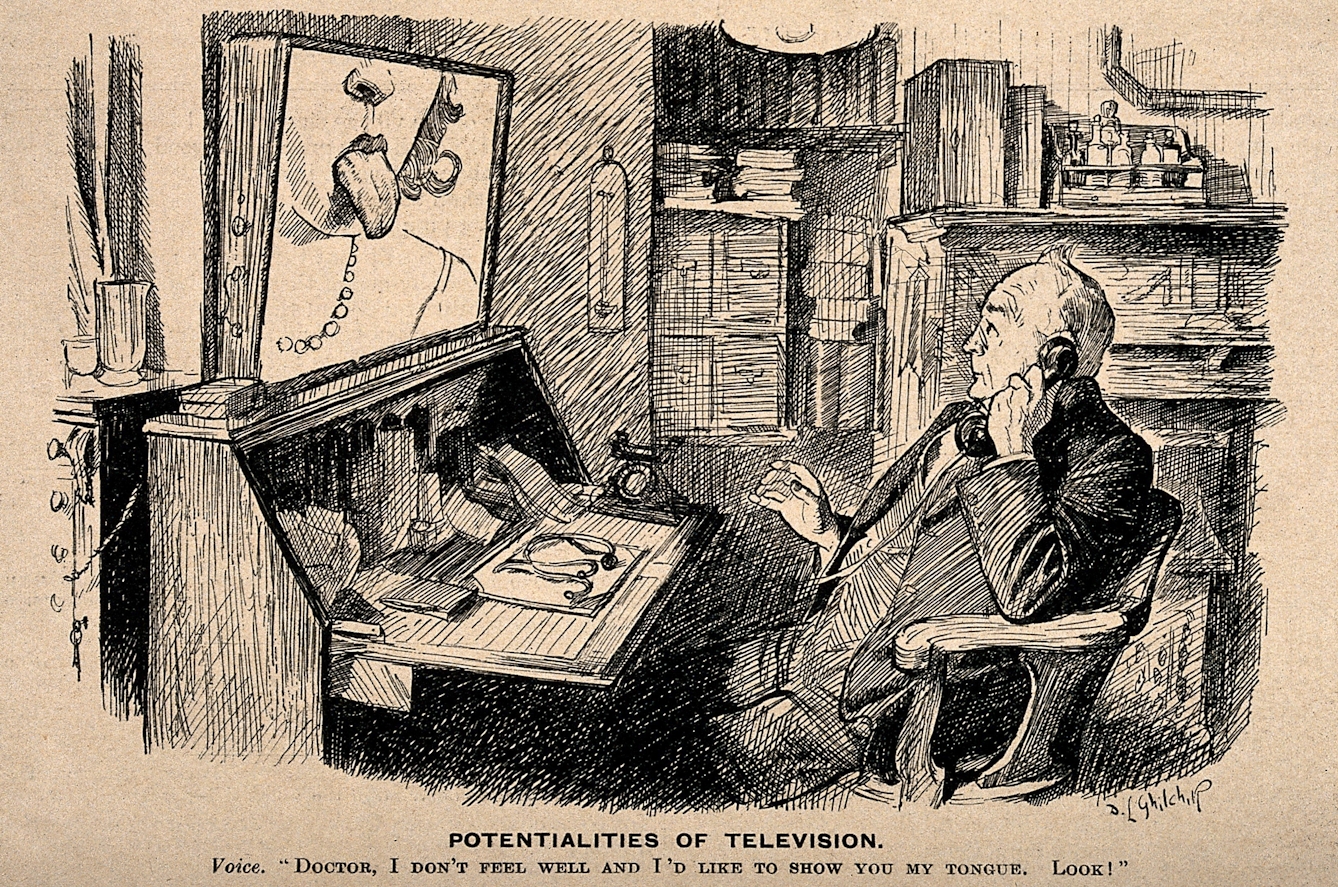

In the early years of screen technology, the idea that we could virtually connect with other people, such as doctors, was a joke rather than a serious possibility.

Gamers, too, can suffer genuine side-effects. A 2015 report by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) stated that: “Studies suggest that when […] individuals are engrossed in internet games, certain pathways in their brains are triggered in the same direct and intense way that a drug addict’s brain is affected by a particular substance. The gaming prompts a neurological response that influences feelings of pleasure and reward, and the result, in the extreme, is manifested as addictive behaviour.” That study is now a few years old, and since then the technology and game-play worlds have become progressively more real.

But as we move into a world of increasingly advanced human–machine interfaces, will immersing ourselves in virtual reality (VR) be considered a form of intoxication?

A flood of sensation

What makes VR very different from traditional gaming is the use of senses other than sight and sound. Touch is a sense that isn’t present during video gaming (except for operating some kind of interface device) and yet it’s the one sense that adds a genuine feeling of reality.

Tabletop gamer and writer Ian Williams says, “I crave touch in a world which is increasingly made of wireless signals and broadband. It can’t be duplicated in video games. I can see the sun outside my window, turn to my screen and see a facsimile of it. I can hear a bird chirping and hear it through my speakers. Taste and smell can’t be duplicated, but neither is as omnipresent or vital to the day-to-day human experience as sight, sound and touch.”

Taste and smell may not be present in video games, but VR is adding them to the mix with specialist headsets, gloves and sensory masks that promise to engage all of the senses. One such device, the Feelreal mask, has the ability to waft scents under the user’s nose, have small fans blow wind into the face and even simulate heat, water mist and vibration. And that’s just one of many such devices on the market.

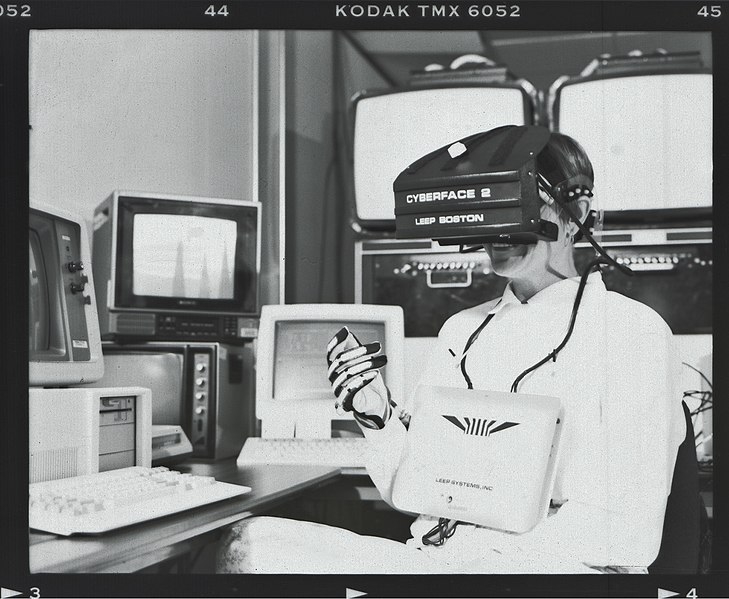

Exploration of the technologies and possibilities of virtual reality has been taking place for decades. The Institute for Simulation and Training at the University of Central Florida was established in 1982.

“The thing about VR is its ability to allow the user to feel he/she ‘is there’, a phenomenon we call ‘presence’,” explains Benjy Li, a postdoctoral researcher with Stanford's Virtual Human Interaction Lab. “We see greater influence of VR when users report higher levels of presence.” He believes that using VR to trick our senses could lead to new therapies. “For example, the smell of gunpowder might be used in treating certain cases of PTSD, or lavender, to create a calming effect.

“In the future we could use VR to trick our brains into eating healthier, both for ourselves and the planet. What if one day we are able to show you, in VR, a piece of steak, with the smell and scent that goes along with it, and you cut it up and feel its tenderness, and you enjoy every bite of it? But in real life, it's made of plant-based ingredients.”

In this study, virtual reality was used as therapy. It enabled individuals with paranoia to experience everyday social situations (such as train rides or lifts) that they found difficult, whilst they were guided by psychological techniques. Their learning in the virtual world transferred to the real world.

Zero-calorie, sustainable eating

As it happens, Project Nourished is already experimenting with this concept. It uses a headset, an aromatic diffuser, bone-conduction headphones, virtual gyroscopic utensils (to give a sense of weight and mass) and 3D-printed food to simulate any kind of meal in any setting. It allows you to feel as if you are sitting on a balcony in Paris eating the finest cuisine, or even to taste foods that are ‘impossible’, such as dinosaur steaks or fruits from alien planets.

Merging the sciences of molecular gastronomy and VR will, the project claims, “make food more sustainable by utilising ingredients such as algae, yeast and insects. The technology can even be used to preserve foods for the future generations by creating chemical and digital carbon copies; in case of overfishing or natural disaster.”

In the very near future we may well see virtual sex apps that allow people to sleep with their fantasy partners. You will be able to enjoy the full sensory experience of flying like a bird or walking on the surface of Mars. You’ll be able to eat anything, even taboo or illegal foods such as endangered or extinct species or even human flesh. And you’ll be able to walk through ancient Rome and hear, see, smell and touch the world as Julius Caesar experienced it.

We have many more senses than the traditional five: we have balance and proprioception, the sense that tells us where our limbs are in space; we have sensitivity to heat and cold, light and dark; we can sense changes in air pressure and velocity; we can sense movement and the passage of time. As more senses are incorporated into VR, each adds an extra layer of physicality and feeling of ‘realness’. And as they become more and more real, the likelihood that these experiences will become intoxicating – possibly to the point of addiction – is quite high. The damaging effects of overindulgence surely won’t be far away.

Ela Darling, pornographic actress and co-founder of virtual reality company VRTube.xxx, asks a question about potential uses of consumer VR at a conference. Darling first used virtual reality technology to record an erotic scenario in 2014.

Getting away with (virtual) murder

We live in a world where people, for whatever reason, are driven to do bad things. So what is to stop them doing bad things in VR?

In video games we can do certain things – such as commit murder – that we cannot do in real life. We can also indulge in illegal acts such as destruction of property, torture, theft or sexual molestation (the one current exception to this is child pornography; possession or creation of sexual images of children – even in cartoon or CGI form – is a criminal offence). There are even games that allow you to commit acts of cannibalism, although this is not actually illegal: there is no statute that prohibits eating human tissue (which is why you can buy freeze-dried placenta online). However, almost every way that you would obtain human flesh is illegal.

Whether eating people or committing murder, gamers today are at a remove from their actions, operating via controllers and with the room around them to put the on-screen action into context. However, when all of their senses are engaged, how will these kinds of activities affect the user? It’s interesting to note that, when Michael Crichton made the 1973 film ‘Westworld’, he anticipated some of the issues we’re discussing. He envisaged the creation of a theme park in which everything is ‘real’ and in which you can physically interact with realistic human androids. And what do visitors do when they visit? They use the androids for sex or they kill them. As Larry Alan Busk writes: “The resort is something of a playground of aggression. It is part of the ‘amusement’ of Westworld to murder others in arbitrary, pointless saloon disputes.”

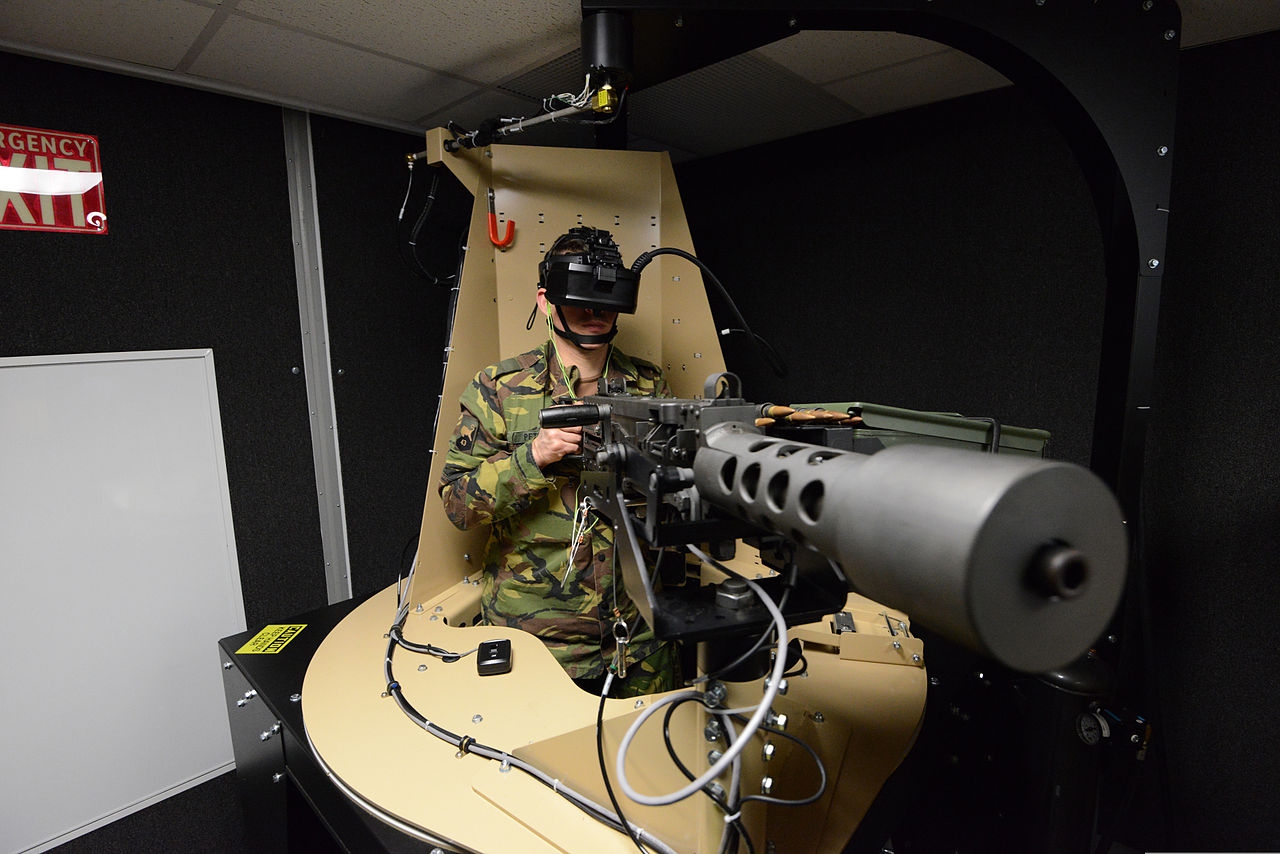

Virtual reality is used to train soldiers, providing experiences of battle and killing. As part of the 2014 European Union Battlegroup, about 1,500 soldiers from Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Spain and Macedonia took part in a virtual reality quick-reaction infantry task force.

Visitors to Westworld initially experience a degree of reticence to fully immerse themselves. But once they do, the killing becomes fun and they feel no remorse. As VR brings reality closer to the world of science fiction, will the realism of the experience make the user feel any remorse, shame or horror for what they’ve done? Or will we able to divorce our sensibilities from the apparent reality that we’re experiencing, like in the film?

Virtual intoxication

If, as games developer John Carmack says, “virtual reality is about being freed from the limitations of actual reality”, then that also, temporarily, frees us from societal rules regarding morality. If the brain really does see VR as similar to an actual experience, then we’re suddenly into a whole new ballgame in terms of how VR affects us, and how intoxicated we become with virtual experiences.

VR is, quite literally, a whole new world, and one that we’ve barely begun to explore.

About the author

Stevyn Colgan

Stevyn Colgan is an author whose debut novel, 'A Murder to Die For', was shortlisted for the Penguin Books’ Dead Good Readers’ Awards. For more than a decade he was one of the ‘elves’ that research and write the TV series 'QI', and he was part of the writing team that won the Rose d’Or for BBC Radio 4’s 'The Museum of Curiosity'. In his previous career he was a police officer in London for 30 years.