The irresistible lure of the transitory high has led to our legal love of nicotine, clandestine craving for cannabis, and even a lust for laughing gas. ‘Healthier’ alternatives like vaping are now in fashion, but perhaps half the fun comes from knowing they’re bad for us.

Inhaling happiness and gasping for a high

Words by Stevyn Colganaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

I was out walking my dogs in some local woods recently and took a route through a small spinney of hazelnut trees. In the centre is a clearing popular as a hangout for young adults. On the ground I found a handful of small silver cylinders that looked like aqualung equipment for an Action Man or Barbie. I recognised them as ‘whippets’ – nitrous-oxide cylinders of the kind used in whipped-cream dispensers, also known as whip-its, bulbs, NOS, hippy crack, balloons and sweet air.

However, they are also used as an intoxicant. You use them to inflate a balloon, so the nitrous oxide can then be self-administered in small doses to achieve a mildly narcotic high. In the UK it is estimated that almost half a million young people use nitrous oxide recreationally.

Whippets often litter public spaces and some councils have reported the significant efforts required to clean them up.

Whippets are the latest in a long line of intoxicant crazes and, like their predecessors, they carry a degree of risk. The high comes from the gas replacing oxygen in the brain and creating a mildly ‘drunken’ state. However, too much can cause blackouts and, according to Dr Harris Stratyner, regional vice president at Caron Treatment Center in New York, “There is evidence that abusing nitrous oxide causes ‘dark holes’ in the brain, in areas that have been deprived of oxygen and brain cells have been destroyed. If you use a lot of it, you’re not going to wake up.”

Whippets hit the headlines in 2011 when Hollywood actress Demi Moore was hospitalised after alleged heavy usage. And deaths do occur; in March 2015, a student from the University of Brighton was found dead with 200 used cylinders in his room. An inquest found that he died of asphyxiation as a result of the chronic use of nitrous oxide. Consequently the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 was enacted, which made it illegal to possess and/or use nitrous oxide as an intoxicant... although there has been a great deal of confusion about applying the law. The act excludes ‘medicinal products’ and some courts have held that nitrous oxide is just that, while others haven’t. More case law will be needed before we arrive at a definitive answer.

Meanwhile, whippets are as popular as ever: London’s Tower Hamlets Council announced that between August 2017 and January 2018 its street cleaners had picked up 1.2 million cylinders.

Victorian laughing-gas parties are depicted in various humorous prints from the era.

The use of nitrous oxide is actually nothing new. Victorian scientists, poets and members of the aristocracy would indulge in fashionable ‘laughing gas’ parties, so named for the sense of euphoria that many experienced. Robert Southey, the English Romantic poet, described it as “a sensation perfectly new and delightful”.

And, in December 1838, the Northern Liberator newspaper reported that three leading academics – Dr Henry Phillpotts (Bishop of Exeter), Dr Edward Bouverie Pusey of Oxford and a Dr Bowring – had tried the gas and then “looked at each other with great earnestness, then grinned with Satanic feeling, and ultimately burst out in the most frantic fits of laughter”. Sir Humphry Davy (perhaps best remembered for inventing the miners’ safety lamp), who first recognised its possible use as an anaesthetic, experimented with it so much that he became addicted.

Demonising cannabis

However, nitrous oxide was a healthier alternative to opium – also popular in the Victorian age – and to tobacco, which remains the most popular legal high after alcohol. But, like alcohol, tobacco is also one of the most damaging. Smoking accounts for 484,700 hospital admissions per year (around 4 per cent of all hospital admissions). Meanwhile, 22 per cent of all admissions for respiratory diseases, 15 per cent of all admissions for circulatory diseases, and 9 per cent of all admissions for cancers between 1980 and 2018 were estimated to be attributable to smoking.

The harm caused by tobacco smoking is one reason why there has been an almost continuous campaign to allow the recreational use of cannabis to be made a legal alternative. The reasons why cannabis became illegal are complex; some claim that it’s the fault of the former head of the US Department of Prohibition, Harry Anslinger, who whipped up national hysteria to the drug following the case of Victor Licata, a young man who, in 1933, killed five members of his family with an axe. Anslinger told Americans that the cause was the “the demon weed” (despite the fact that there was no evidence of cannabis use).

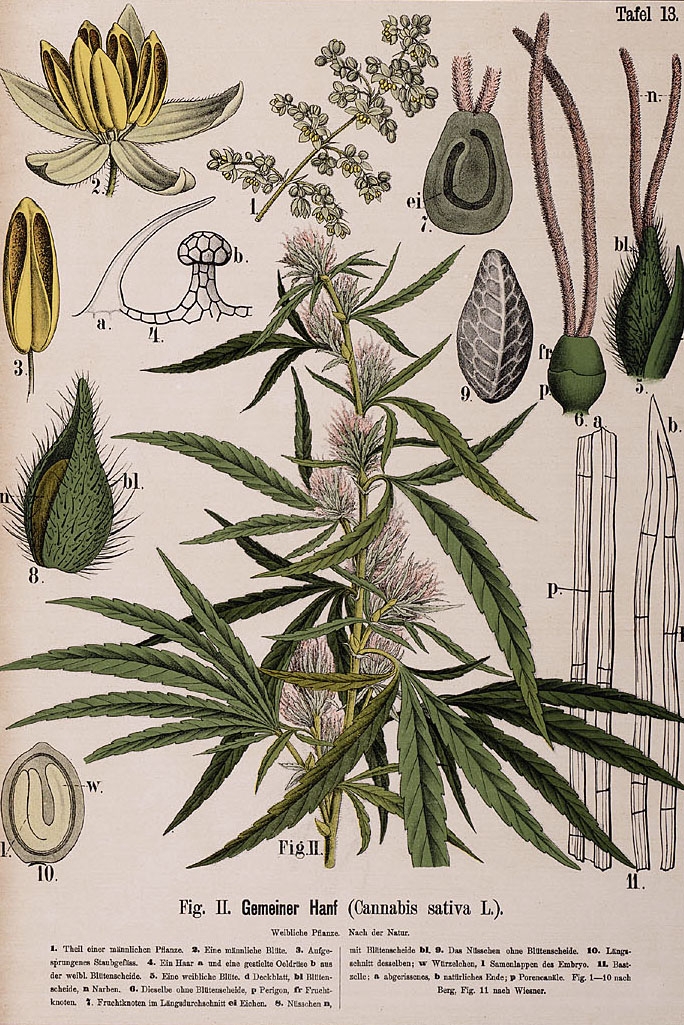

Cannabis was depicted innocuously beside other plants in many botanical sources before it became thought of as the demon weed.

This was further reinforced by a notorious 1936 propaganda film called ‘Reefer Madness’, in which teenagers were seen to commit all kinds of crimes, including hit-and-run accidents, manslaughter and attempted rape, before suffering hallucinations and madness due to alleged marijuana addiction.

Others will point to the fact that tobacco and timber were hugely valuable cash crops and that cannabis hemp threatened both industries (hemp fibres can be used to make paper). Still others will tell you that criminalisation was partly motivated by fear of Mexican immigrants.

Eric Schlosser in his 2004 book ‘Reefer Madness: Sex, Drugs, and Cheap Labor in the American Black Market’ says: “The prejudices and fears that greeted these peasant immigrants also extended to their traditional means of intoxication: smoking marijuana. Police officers in Texas claimed that marijuana incited violent crimes, aroused a ‘lust for blood,’ and gave its users superhuman strength. Rumours spread that Mexicans were distributing this ‘killer weed’ to unsuspecting American schoolchildren.’

Whatever the reasons, cannabis remains illegal in much of the USA and the UK, despite the fact that the number of cannabis-related deaths in 2017 was just 29 (although, of course, cannabis is not widely available to users in the way that tobacco is). The debate around legalisation will doubtless continue for years to come.

When tobacco goes up in smoke

In the meantime, ‘vaping’ has become the accepted legal alternative to tobacco. But is it healthier? A report by the Royal College of Physicians believes so. Among its list of conclusions are the following observations:

- The hazard to health arising from long-term vapour inhalation from the e-cigarettes available today is unlikely to exceed 5 per cent of the harm from smoking tobacco.

- Technological developments and improved production standards could reduce the long-term hazard of e-cigarettes.

The report does express some concerns that e-cigarettes could increase tobacco smoking by normalising the act of smoking and by acting as a gateway to smoking in young people. However, it concludes that: “The available evidence to date indicates that e-cigarettes are being used almost exclusively as safer alternatives to smoked tobacco, by confirmed smokers who are trying to reduce harm to themselves or others from smoking, or to quit smoking completely.”

Pipes in pictures

Made between 1815 and 1820, this pipe and the ‘finger’ tamper were designed to be portable. The gentleman smoker came to the fore during the 1800s, and pipe smoking became a serious hobby among wealthier men.

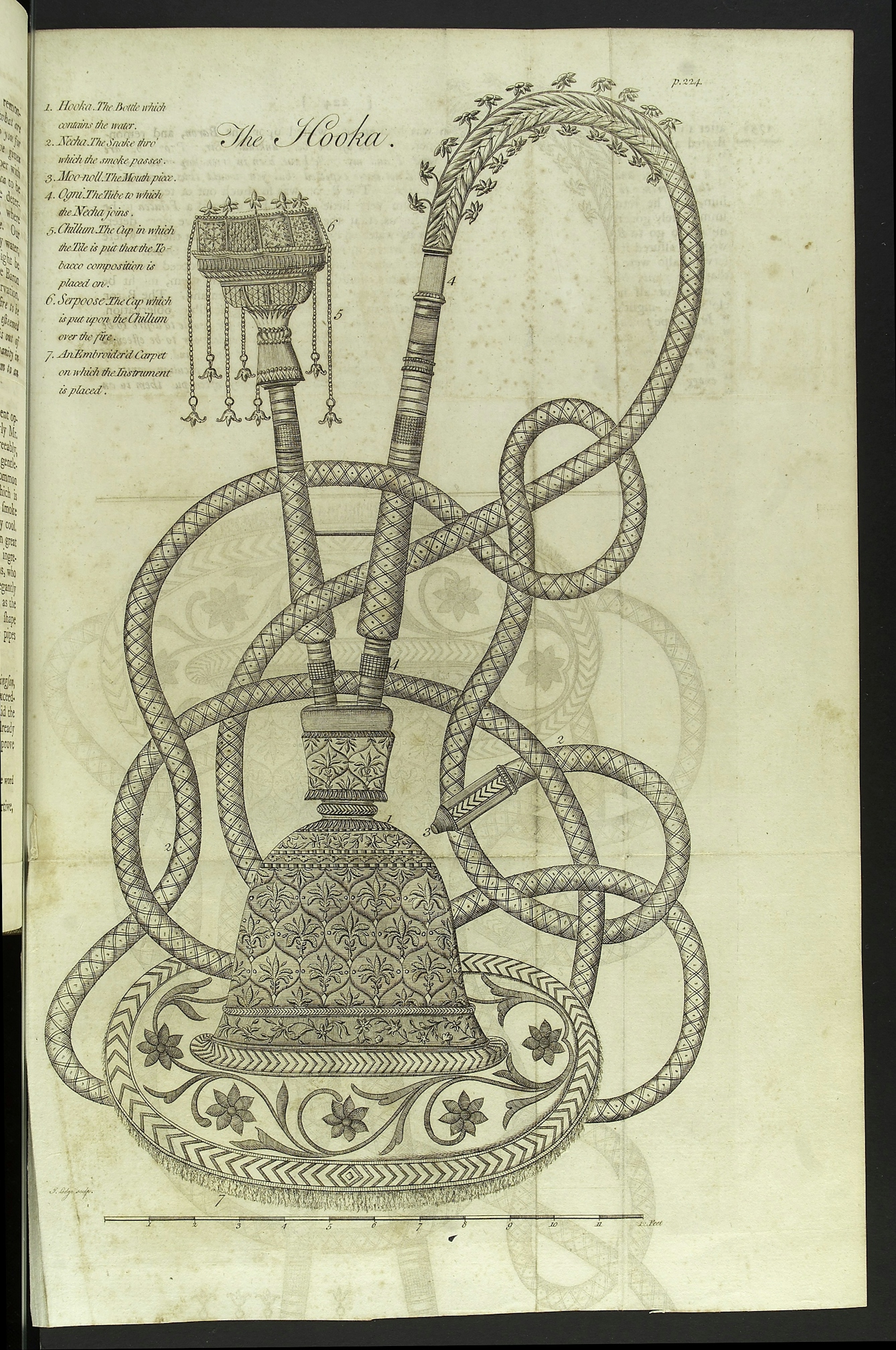

In 1773, Edward Ives explained the hookah in his book ‘A Voyage from England to India’: “The smoke passes through water before it enters the mouth, and is thereby very cool… [the tobacco] too is of a mild kind… made into a paste with sugar, scented ingredients, and rosewater, and thus smoking is made agreeable to persons who would otherwise dislike it.”

These very simple pipes date from as early as 1580. When tobacco was first introduced it was expensive, so this meant that pipe bowls were quite small. The clay pipes themselves were inexpensive and popular but easily broken.

These ornate pipes from the late 1800s were likely to have been given as gifts or bought as souvenirs. One was thought to have been owned by the chairman of an Oxbridge students’ smoking club.

Either tobacco or opium could be placed in the well of a water pipe. This example is elaborate, with enamelled flowers and foliage engraved onto it to reflect the wealth of its owner.

So, for the moment, at least, e-cigarettes would seem to be the safer option. However, the safest option will always be abstinence. Although e-cigarettes contain fewer harmful substances than tobacco products, they do contain nicotine, the primary reason for smoking, which is a toxic substance. It raises your blood pressure and spikes your adrenaline, which increases your heart rate. A few people have even used liquid nicotine to take their own lives, the first being Jonathan Keen in 2015.

What is needed is longer-term data on the effects of using e-cigarettes, particularly in regard to cardiovascular disease. But this will take time; vaping has only been with us in the UK since 2007.

People will always look for ways to trigger that hit of dopamine that we find so intoxicating. In the past it has led us to using harmful substances like tobacco, chemical solvents and opiates. In most instances, we had no idea of the long-term harm that these drugs would do to us. Now that we do, a whole new industry has arisen to find safer alternatives. Whether people want a safe alternative is another discussion, however.

Sometimes the thrill of doing something wrong or illegal can be just as intoxicating as any substance.

About the author

Stevyn Colgan

Stevyn Colgan is an author whose debut novel, 'A Murder to Die For', was shortlisted for the Penguin Books’ Dead Good Readers’ Awards. For more than a decade he was one of the ‘elves’ that research and write the TV series 'QI', and he was part of the writing team that won the Rose d’Or for BBC Radio 4’s 'The Museum of Curiosity'. In his previous career he was a police officer in London for 30 years.