The first public museums evolved from wealthy collectors’ cabinets of curiosities and were quickly recognised as useful vehicles for culture. But how have historical and sociopolitical circumstances shaped museums? And, in turn, how have Western museums presented culture to the people?

The birth of the public museum

Words by Elissavet Ntouliaaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

The first public museum

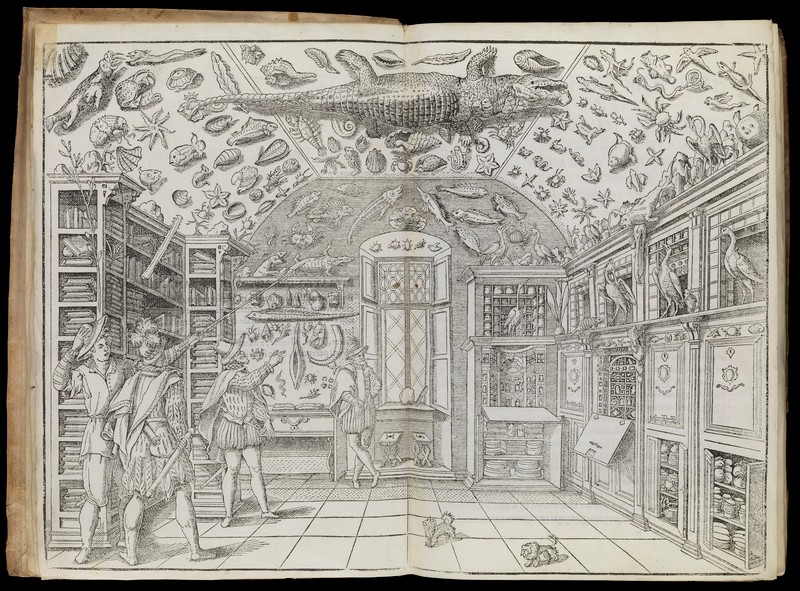

Most museums are built around a collection, and our journey starts in the 16th century with the so-called ‘cabinet of curiosities’. Composed of rare and unusual objects, they were collected with the purpose of being preserved and interpreted to ultimately offer an understanding of the world. Their owners, some of the first systematic collectors, were royalty, noblemen and affluent merchants.

In the 1600s, John Tradescant’s house and garden in South London were filled with more curiosities than someone might see in a lifetime of travel, all thanks to his employers and other connections.

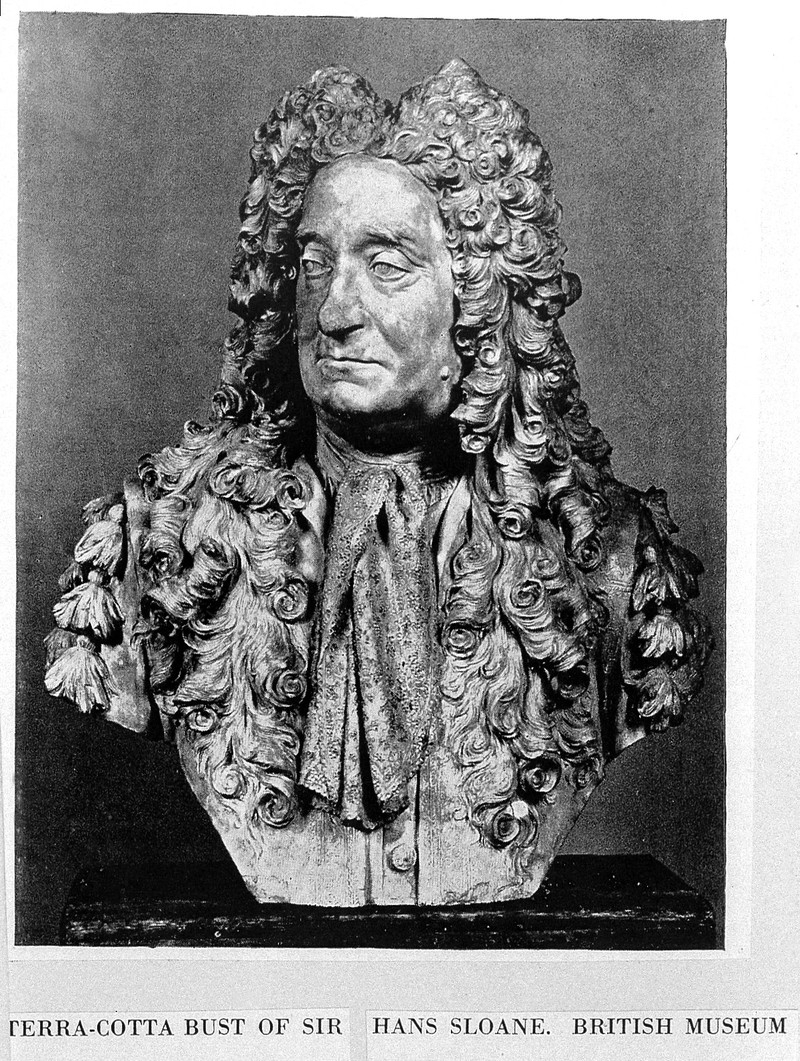

Collections such as these formed the basis for the first public museums in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. In Britain, the British Museum was formed in 1753 by an act of Parliament, comprising Sir Hans Sloane’s collection (who had bought the cabinet of the London apothecary James Petiver).

However, the French Revolution in 1789 and the emergence of the nation-state in Western Europe had a profound effect, making these aristocratic collections available to the public.

The opening of the palace of Louvre as a public museum in August 1793, with artworks previously owned by the king and the Church, served as a symbol of political success for the new Republic and a physical manifestation of the principles of liberté, égalité, fraternité.

In pictures

The earliest illustration of a natural history cabinet: Ferrante Imperato, ‘Dell’Historia Naturale’ (Naples, 1599).

Sir Hans Sloane in the British Museum.

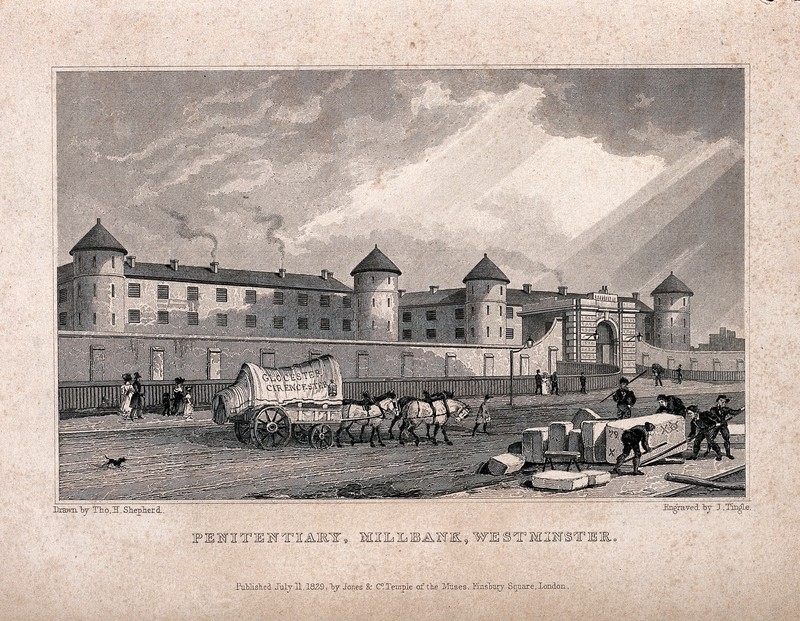

Engraving of the Penitentiary, Millbank, on the site of Tate Britain.

Culture turned out to be a useful vehicle for governments in their effort to transform the masses into ‘citizens’; museums were referred to as ‘civic engines’.

In 1888, the publisher Thomas Greenwood proclaimed public museums and libraries a state affair as indispensable for municipalities as drainage, the police and lunatic asylums.

Institutional buildings were repurposed to house the new, reforming institutions: Tate opened its doors to the public in 1897, on the site of the Millbank Penitentiary.

Museums were also seen as providing a more ‘appropriate’ form of entertainment for the people. As anthropologist Franz Boas put it in 1907, a visit to the museum “counteracts the influence of a saloon and of the race-track”.

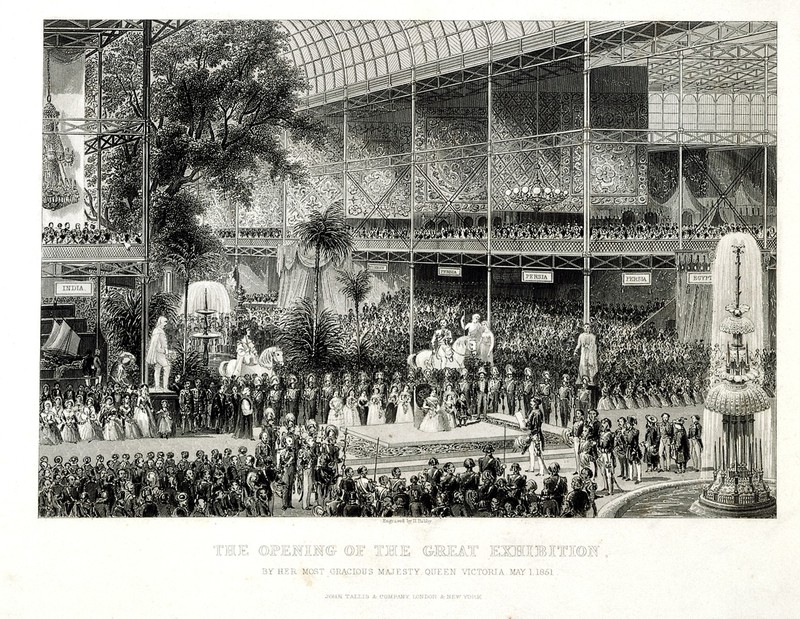

Along with democracy and liberalism, the Industrial Revolution (with its epicentre in Britain) gave birth to another key relative of the public museum: the international exhibition. London’s ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’ in 1851 set the model for similar exhibitions in other countries showcasing advances in manufacturing, science and technology.

The exhibition was promoted as celebrating international cooperation and peaceful competition among nations. However, the numerical superiority of British exhibits and the exhibition’s division between ‘Britain and her empire’ and ‘the rest of the world’, meant it was ideologically loaded as a celebration of Britain’s political and economic supremacy.

The Victoria and Albert Museum, along with the entire South Kensington cultural area, including the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum, owes its existence to the Great Exhibition: it was built from its surplus.

Henry Wellcome and his collection

Henry Wellcome’s collection has been regularly compared to the Wunderkammer (German for ‘wonder cabinet’, like the aforementioned cabinets of curiosity). Despite Wellcome’s fascination with bizarre and extraordinary objects that often defy categorisation, his collecting seems to be in tune with his time.

The 1851 exhibition showed that collecting could not be a matter of private interest any more, but should form part of the wider debates linked to political and social changes. However, the habit of collecting was still strongly connected with prestige and power; it was embraced by the new wealthy, an emerging middle class of businessmen and entrepreneurs.

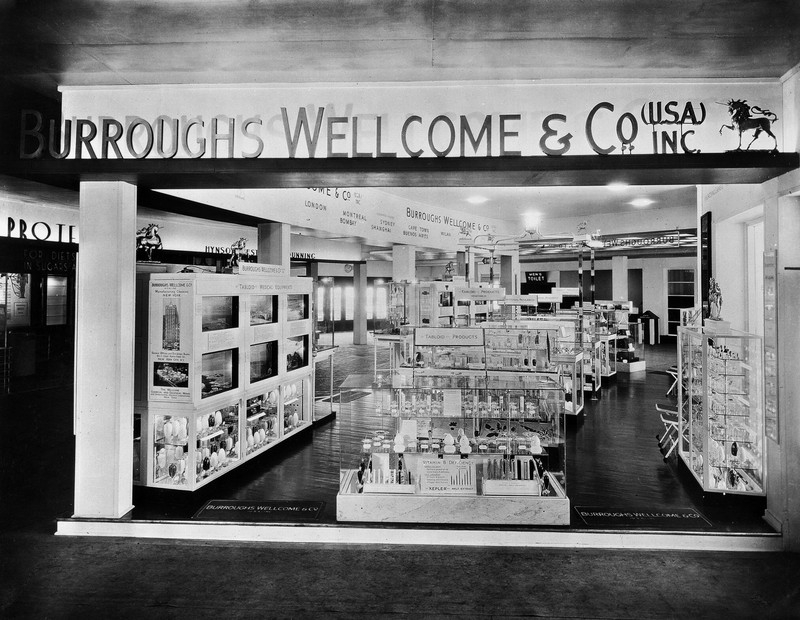

Wellcome, a clever entrepreneur himself, detected early the immense potential offered by these international exhibitions to promote his pharmaceutical company. Consequently, Burroughs Wellcome & Co showcased their innovative products at the 1893 ‘World’s Columbian Exposition’ in Chicago, which served as a demonstration of the superiority of American progress and civilisation.

The ascension from the ‘primitive’ to progress and science was also problematically illustrated by placing native peoples alongside products in the service of the fair’s goal: the education and entertainment of a Western audience.

In pictures

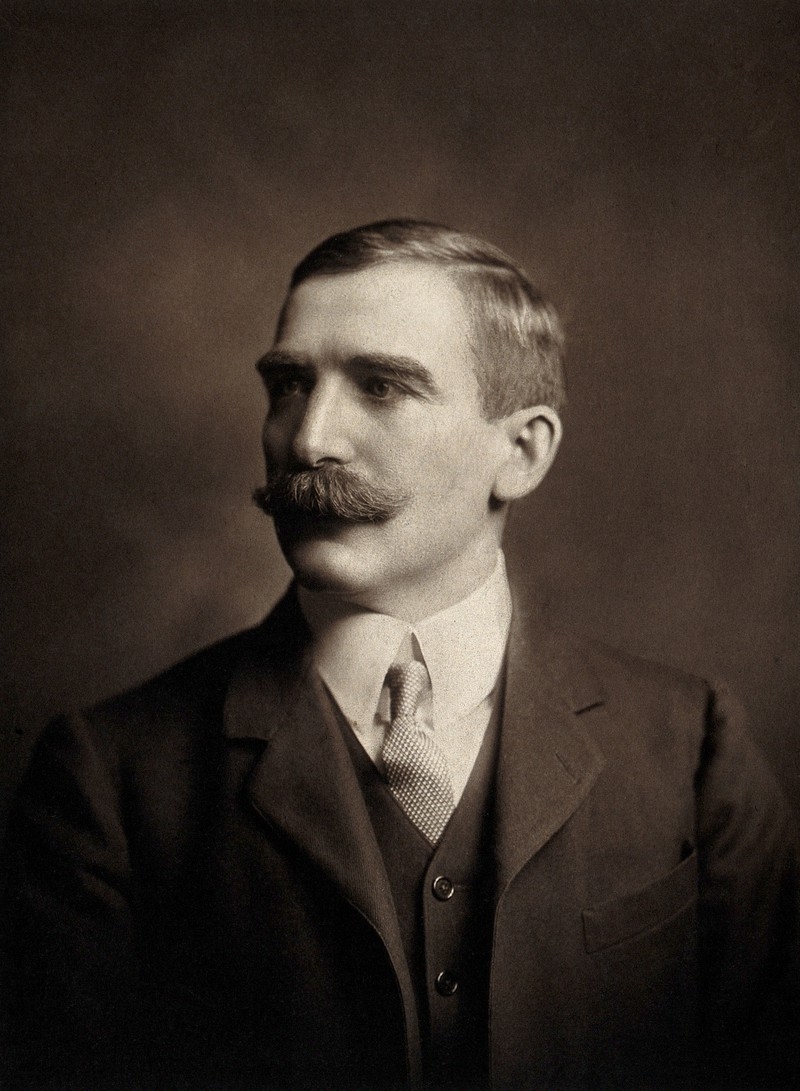

Sir Henry Wellcome

Exhibit at ‘Century of Progress Exposition’

Figures with symptoms of tropical diseases in the ‘Hall of Primitive Medicine’, Wellcome Historical Medical Museum.

Back in the UK, following the South Kensington era, museums and galleries continued to multiply in and outside London with their collections reflecting the technological innovations of the time, as well as echoing the colonialism of the world’s fairs and Darwinian ideas on the evolution of humanity.

The modern museum, the postmodern museum?

Wellcome’s Medical Historical Museum was not a public museum, but interestingly it shared some of these elements: his collection of objects across cultures and time periods was organised to demonstrate man’s progression as a linear process from the savage barbarian to the civilised. Additionally, his later museum on Euston Road was (and still is) housed in a building of imposing ancient Greco-Roman architecture, as are many other museums, implying the ‘ritual’ of enlightened transformation that could take place in these new temples of knowledge.

Mordaunt Crook claimed the modern museum is “a product of Renaissance humanism, 18th century enlightenment and 19th century democracy”. Then what about the 21st century postmodern museum?

In the 2016 Culture White Paper, the British government considered culture as integral for the inspiration of younger generations, the rejuvenation of communities and the empowerment of the British identity internationally. However, a 2015 survey by the Museums Association showed that museums’ main priorities are fundraising and income generation, with community involvement and projects that deliver social impact falling lower down the list.

In terms of collecting and identity, museums appear to want to adapt to a more connected world. The former director of the British Museum, Neil McGregor, promoted the BM as a universal museum that serves “a worldwide civic purpose”. But isn’t the narrator of this ‘world story’ still very much a Western one?

Tate has created philanthropic acquisition committees, formed mainly by wealthy private collectors from around the world, in an effort to increase its acquisitions of modern and contemporary artworks from geographical regions that previously have been neglected from mainstream institutions in the 20th century. But what are the implications of the involvement of wealthy private collectors in institutional collecting and big corporations funding museum narratives?

While they are undeniably complex (and often uncomfortable), conversations around museums' colonial histories are critical in opening the doors on the important issues and responsibilities that exist alongside holding such a wealth of multicultural artefacts.

About the author

Elissavet Ntoulia

Elissavet Ntoulia is a Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.