Many cultures around the world celebrate death as part of life, though we often contain death within designated spaces of our hospitals and cemeteries. From Victorian mourning etiquette to Mexican skeleton decorations, explore how different traditions think about the end.

Death around the world in ten objects

Words by Elissavet Ntoulia

- In pictures

Ancient Egyptians mummified their dead to preserve the body for the return of the soul after the perilous journey of the afterlife. Animals were also mummified for several reasons: to accompany the dead in the afterlife, or to be given as offerings to gods. Cats were related to Bastet, the goddess of fertility, protection and pleasure, often depicted with the head of a cat. Contemporary research has revealed that in some cases animal mummification followed the same detailed preparation as for humans, although in other cases animal mummies sometimes barely contained any animal parts at all when demand overwhelmed supply. There was an industry that bred animals specifically destined to be killed for mummification, which was considered a great honour and would secure them a place among the gods.

This papier-mâché skeleton is from the Lake Pátzcuaro area at Michoacán, Mexico, made as part of the decorations for the Day of the Dead festival (El Día de los Muertos), celebrated across Mexico annually. However, only in Pátzcuaro, the celebrations begin with the Night of the Dead: all-night candlelight visits to the cemeteries at sunset on 1 November. This family and community feast, when the dead are believed to return to the earth, comes from ancient pre-Hispanic beliefs about afterlife and their associated rituals, which became integrated into Catholicism after the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the 16th century.

Pagan customs commemorating the dead were deeply rooted in ancient cultures across Europe, but the Christian Church thought of them as superstitious. Bishop Ambrose of Milan in the 380s was among the ecclesiastic figures that tried to restrict funerary rituals such as the habit of feasting at the graves of the dead. Eventually, within Christianity, the cult of the dead and ancestor worship was transformed into the cult of the saints. However, similar gatherings in cemeteries, as in this painting by British artist Reginald Cleaver, still take place in Italy on All Souls’ Day on 2 November.

Death in the form of a skeleton does not distinguish between a king, a farmer and a beggar, as depicted in this 18th century German painting. The Dance of Death imagery served as a memento mori, a reminder of the inevitability of death, linked closely to Christian ideas of a pious earthly life securing a place in the Kingdom of Heaven. Such theological reminders would appear in church murals and prints as well as personal and household items.

Hair jewellery became part of a strict mourning etiquette in Victorian England, as set by Queen Victoria, especially among upper class women. Following the memento mori tradition, they served as material reminders of human mortality and of departed loved ones. Death offered a commercial opportunity for the Victorians, who developed an industry around it, involving extravagant funerals, grave monuments, and elaborate hearses replete with black horses, ostrich feathers and flowers.

This ceremonial headdress from Nepal is partly made of a human skull. Human bones are used in Buddhist sacred objects as signifiers of life’s impermanence. They also reinforce the concept of embracing the fear of death so obstacles and passions may be transformed and used for spiritual ends. Himalayan Buddhists performed sky burials: leaving a body to the elements and scavenging animals, to decompose naturally on rocky terrain. This practice reflects the idea of the ephemerality of the body over spirit.

Many cultures around the world capture the image of the royal and noble dead to honour and preserve their memory. The Asante (also Ashanti) people of present-day southern Ghana or southeastern Côte d’Ivoire, part of the Akan empire from the 17th century until European colonisation in the early 1900s, created terracotta ‘portrait’ heads of their rulers. During the funeral, they were placed in the cemetery at a sacred grove, while afterwards they were the focus of annual commemorative rites. Asante society is matrilineal, and it is likely that the makers of such objects were female, as clay has primarily been used by women as an artistic medium in many African cultures.

Death masks to honour the important and famous were also made in Europe from the Middle ages. However, the making of death masks of members of society who were considered less worthy, like this one of French criminal Norbert, can be associated with the discriminatory pseudoscience of phrenology. Phrenologists believed that the shape and size of the skull was indicative of personality traits. Plaster casts of executed criminals were therefore used as aids to support such claims.

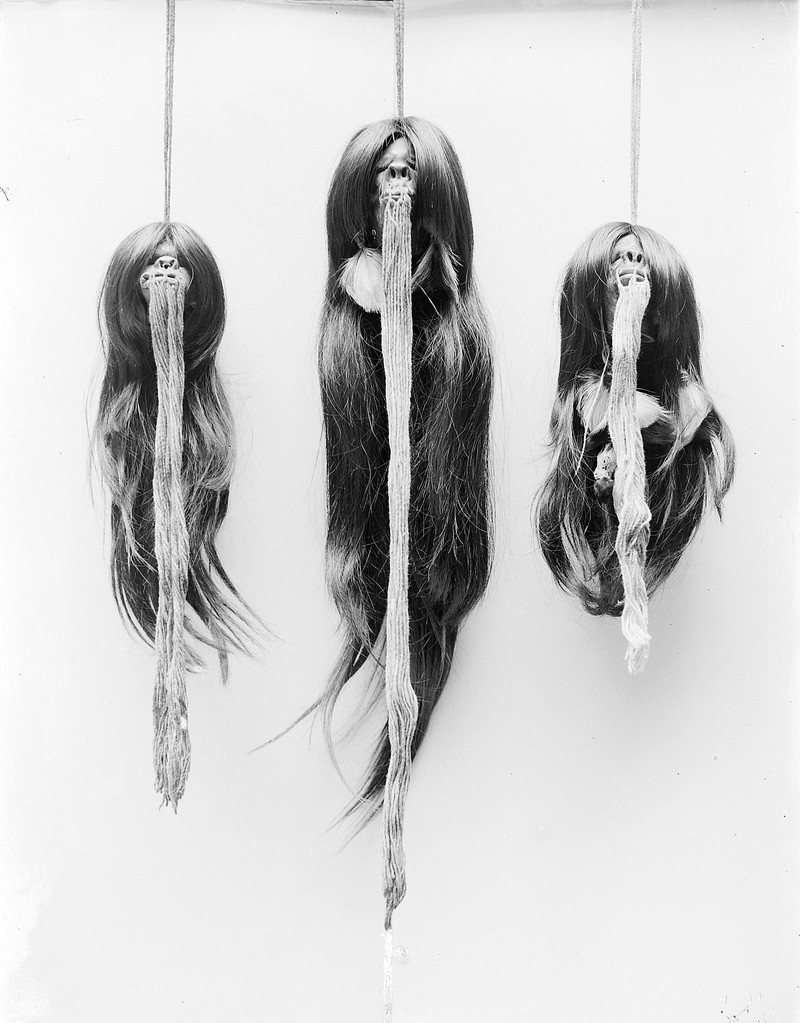

Violent death has been differentiated from death as a natural part of life across cultures and time periods worldwide. The Jivaro people of Ecuador were headhunters and known for shrinking their enemies’ heads (tsantsas). The slayer would hold a feast upon returning to his village with the tsantsa for reasons of prestige but also to make sure that the enemy’s spirit would not seek revenge. However, this practice extends beyond vengeance to survival and the Jivaro belief that spiritual power (arutum), acquired with the transfer of the enemy’s spirit to his killer, can render the killer immune to a similar violent death.

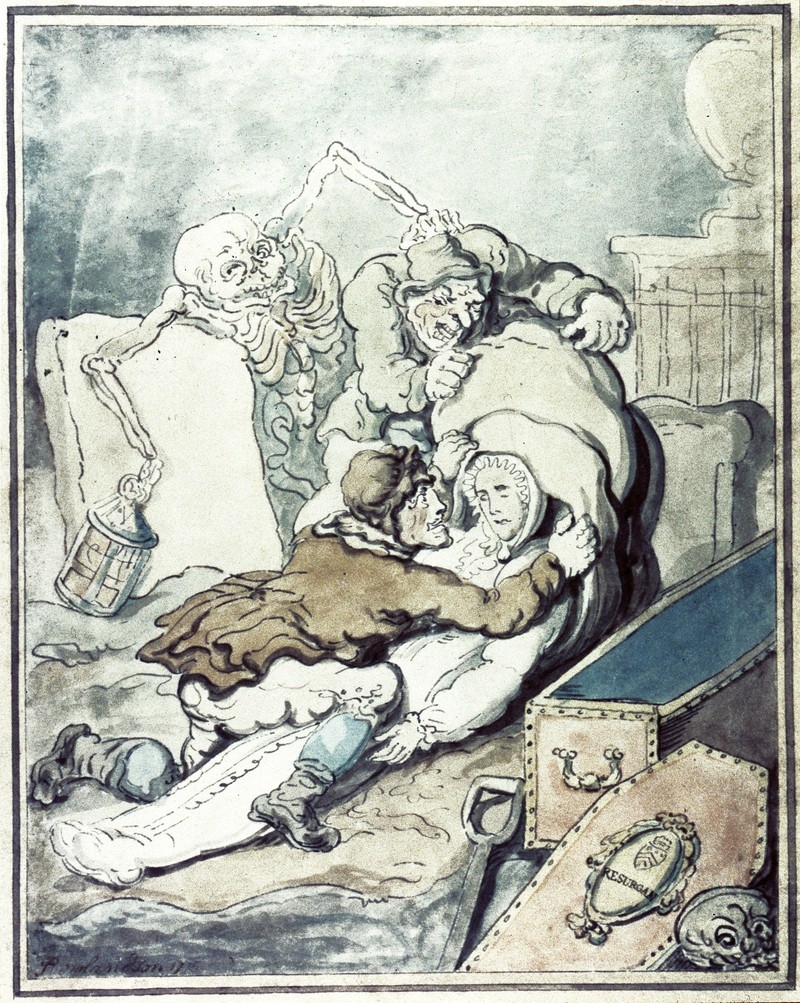

Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical drawing comments on the social consequences of the scientific study of death. Throughout the history of anatomy, the sourcing of dead bodies has been difficult and unethical compared with today’s standards. Before the Anatomy Act of 1832, body snatching had become a profitable private enterprise, responding to the demand for cadavers by British anatomy schools.

About the author

Elissavet Ntoulia

Elissavet Ntoulia is a Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.