A big toothy grin captured by a camera might seem almost an ancient relic in an age of duck-face selfies, but the management of our workplaces increasingly involves a return to capturing smiles.

In this digital age, employers are using more and more sophisticated methods to monitor employees’ behaviour and engagement in their work. For instance, sentiment analytics – also known as emotion analytics – promises to create predictive analytics models for human capital, by crunching data on employee performance.

As well as using online surveys aiming to capture employees’ emotional states, webcams and software are used to track – and manage – emotions, including training workers in appropriate facial expressions. This is particularly relevant in customer-facing environments, such as retail, where managers can monitor how often workers smile at customers.

Many modern cameras are designed to recognise and capture smiles.

“Lift up your mouth corners”

For instance, around ten years ago, the Keihin Electric Express Railway Company in Japan began asking its 500 employees to smile at a computer system each morning. Lip curvature and facial creases were analysed and a rating out of 100 given for smile quality, with feedback, such as “lift up your mouth corners”. Workers could even consult a printout of an ideal smile for reference.

Machines are extending their knowledge of facial expressions beyond the smile too. In June 2018, reports circulated of a “smart classroom-behaviour management system”, used in a school in Hangzhou, China to assess degrees of attention and mind-wandering during classes through computerised facial analysis.

From saying cheese to the sparrow face

Though these examples of smile-capturing systems may seem strange, many of us are already familiar with something that has now become an unremarkable capacity of the contemporary digital camera. Most come equipped with ‘smile detection’ technology. Once it identifies a face on the screen, the software seeks the open eyes and upturned mouths associated with a smile, and will only take the photo when these are detected. The user can choose small smiles or big grins.

Of course, we have simulated emotions in front of machines before. As the camera settled into the world as a familiar, if not a friend, subjects often felt compelled to don a particular look: a smile. The slogan “‘Kodak knows no dark days” was adopted in the 1920s by the dominant photography company, and for decades they focused on using happy experiences and getting people to grin in order to help sell their technology.

Selfie culture has generated distinctive facial expressions as well as tools such as the selfie stick.

The selfie pout has come into being historically: it requires no smile and certainly no laugh. Selfies have their own developing repertoire of stances: the duck face, the sparrow face, the fish gape – the last of which returns teeth to the image, in the controlled way that the Kodak smile sometimes allowed.

These ritualised poses are meant to work as self-advertising, but they function too as absurdities, cartoon-like transmogrifications of the human – mostly women and girls – into animalised forms.

Pixelating our emotions

Even without cameras, there is plenty of emotional work for us to do when we interact with machines. We give up our emotional states constantly, with a tap of the finger. Thumbs-up signs, hearts, sad faces: Facebook calls these emojis ‘reactions’, and labels them ‘Like’, ‘Love’, ‘Ha ha’, ‘Yay’, ‘Wow’, ‘Sad’, ‘Anger’ and so on. The scale tends towards the positive.

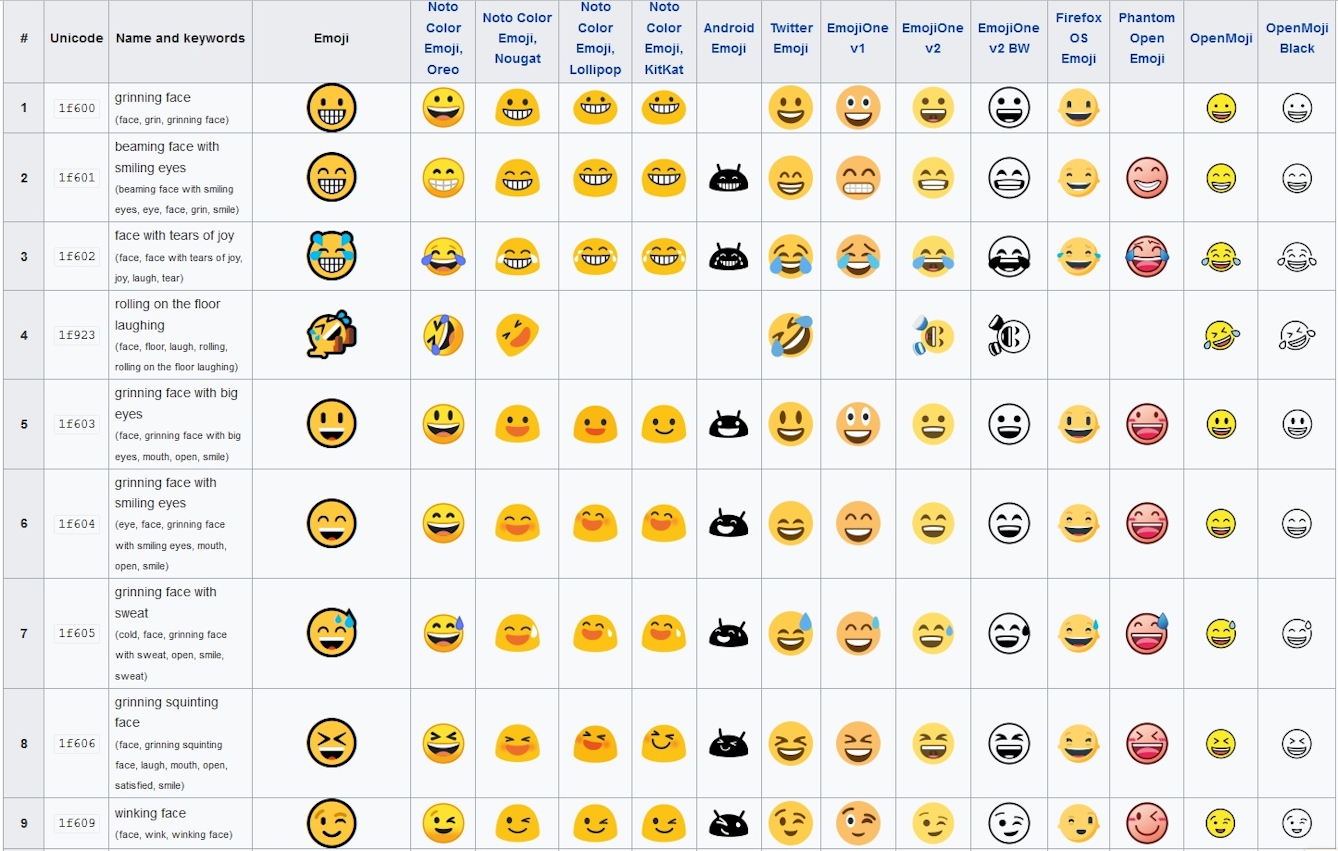

The emoji (Japanese for ‘picture + character’) was invented in 1999 by the pager company DoCoMo, for whom designer Shigetaka Kurita created a set of 176 12-pixel by 12-pixel characters, said to cover the “entire breadth of human emotion”. The palette of emojis continues to expand, including into areas well beyond signifiers of emotions (aubergine, anyone?).

There were originally 176 emojis, but there are now far more to illustrate different moods and scenarios.

Emotion emojis, however, persist. In 2015, Oxford Dictionaries named one, showing a yellow face laughing so much tears gush, its ‘Word of the Year’, because, globally, it had been the most used.

It seems that we have readily accepted the notion that complex emotions can be represented in tiny pixelated characters. By rendering our feelings in this picture language, we have made them into something clickable and machine-readable, unwittingly allowing them to be mined for data by unknown others.

A simpler world

The trend towards simplifying our emotional language has even reached the big screen. The narrative of The Emoji Movie (2018) involves a phone emoji, Gene, whose mood fluctuates. Unable to keep the impassive, unaffected face he is supposed to portray, the ‘meh’ face, Gene is threatened with deletion. *Spoiler alert* The film finds a way to redeem the inconsistent emoji, and Gene is finally celebrated for his unsettled expressions.

But the film world cannot delete the unequivocal emojis either. In Inside Out (2015), Pixar manages to whittle the emotional characters down to five: Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Fear and Anger. These cinematic explorations mirror our over-reliance on the simplification of our emotional language, which certain kinds of data-capture and mining rely on. When simplified emotions are used, the complex actuality of our emotional states and their extremities are subsumed.

Slack is an application that allows people to use and create emojis to signal their mood in the virtual workplace.

Emojis in the office

In June 2018, reports appeared about the “‘fastest-growing business application in history”, Slack, or Searchable Log of All Conversation and Knowledge, self-described as “where work happens”. It is a workplace platform that allows workers to collaborate, share files and tools, and communicate using instant messaging. It gives users the capacity to add emoji buttons to messages, which other users can then click on to express reactions.

In this way, the emoji and its channelling of emotions enter into the heart of the workplace. Or, as Slack’s own HelpCenter puts it: “Emojis are a spin on common emoticons that you can use to add some pizzazz to your Slack messages.” Some critics rage against the “Diet-Coke-and-Mentos-like explosion of cat gifs, bot feeds, and emoji mashups you’ve brought into my life”. Life is, here, the workplace. Others ‘love’ it, and talk of addiction.

Emotion in the workplace is a fraught business. Emojis in the workplace might, on the other hand, add to the maximisation of human resources.

‘Teeth’ is at Wellcome Collection from 17 May to 16 September 2018.

About the contributors

Esther Leslie

Esther Leslie is Professor of Political Aesthetics at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research includes European modernism and the avant garde, Marxism, science, technology and material culture.