Over the past few years Daisy Johnson bounced from GPs to GUM clinics and, after a lot of red herrings, discovered she has vaginismus – an involuntary tensing of the muscle surrounding the vagina. It’s something that often happens to women who have suffered abuse. Although she doesn’t think that’s the case with her, she does believe it has come about, in part, because of inept doctors. Nearly 28,000 women in the UK are estimated to suffer from vaginismus but, like much to do with the female body, it’s rarely spoken about.

ONE

I don’t believe in an afterlife but I sometimes think that when I die I’ll go to the Oxford Sexual Health clinic. It’s in the middle of the hospital – past the sleep study unit, easily missed. They show old films on the television and sometimes you can sit there for four hours without getting an appointment. In the summer, there are sweat stains left on the plastic seats, and cans of Coca Cola rattle out of the vending machine. In winter, the snow and the rain get tracked in. I’ve lost more pairs of gloves there than I’d like to admit. Sometimes, the doctors and nurses forget to turn the intercoms off and you hear everything they say – all the dirty details.

A friend and I went there a lot when we moved to Oxford. Mostly just for check-ups and contraception, but sometimes for thrush or for weird periods or pain. I had my implant put in there and – when it wouldn’t stop itching – dug out again. Do you always bleed this much? the nurse asked me.

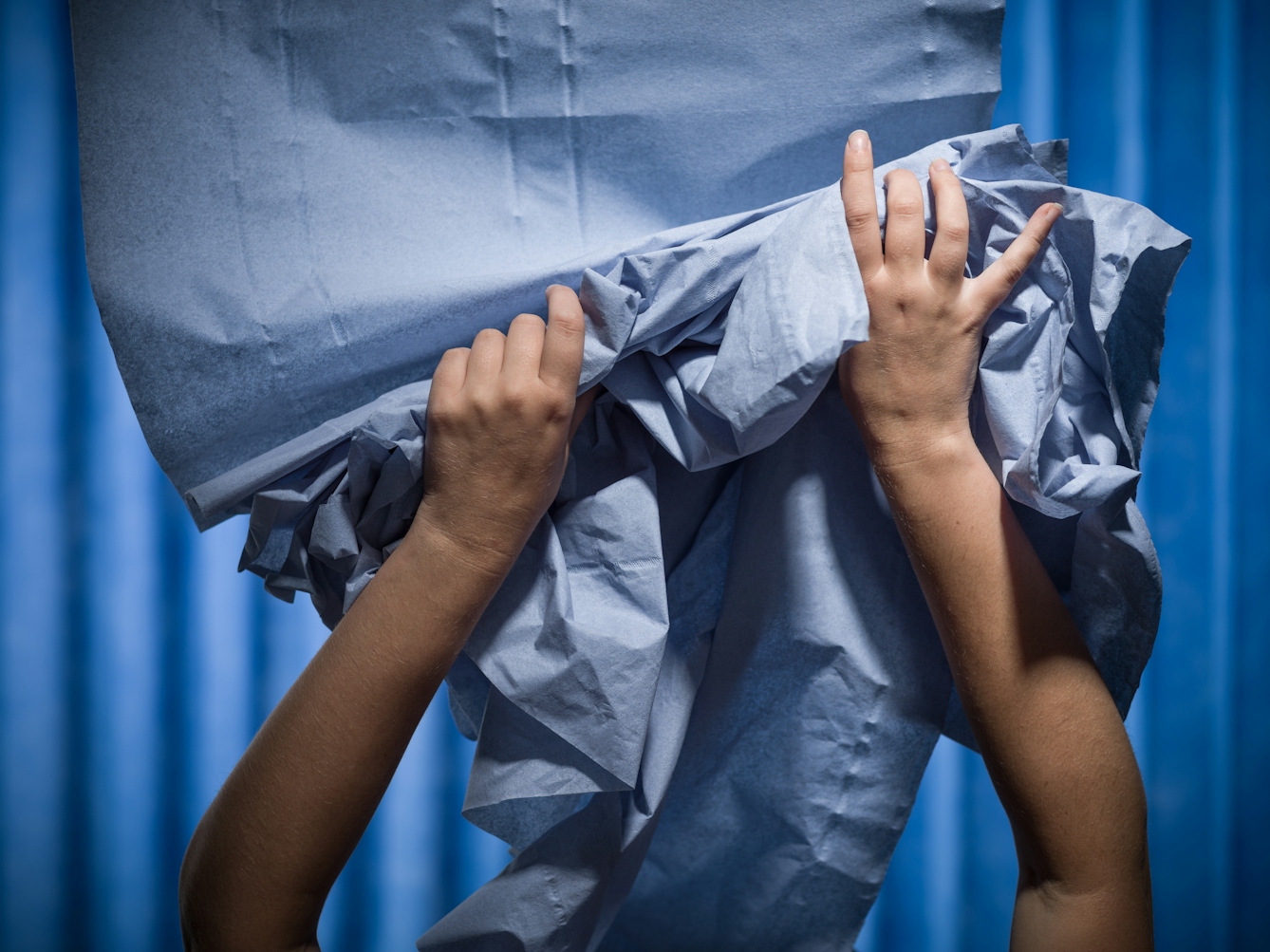

There is – as you sit in the waiting room – always the beginning of panic, the slow creep of anxiety. Anything could happen in those little rooms, the blue paper pulled across the examination tables, the drawers of dentist-like implements. You hope for a good doctor or nurse, for one who listens when you tell them the problem. The best ones hear what you say underneath the words; they understand that when you laugh, it’s not because anything is funny.

I had to go back to the clinic three or four times before they’d take my implant out. It had been itching in the night and I’d scraped the skin hard enough to leave a bruise. The nurse looked me up and down, and said: “You know you’re more likely to get pregnant with condoms, right?” I explained that I did. She asked three or four more times before she’d take the implant out. She didn’t trust me and so I had no reason to trust her.

Anything could happen in those little rooms, the blue paper pulled across the examination tables, the drawers of dentist-like implements. You hope for a good doctor or nurse, for one who listens when you tell them the problem.

TWO

It’s the winter of 2017 and I’m at a friend’s house for dinner. There are five of us and we are – in a way that doesn’t happen often – all women. The friend is a good cook. We eat a lot and drink a bit, and talk about food and movies and politics.

By the time we move to the sofa, we’ve started talking about vaginas, pubic hair and Mooncups and, eventually, awful smear tests. Everyone in the room has something to say: one woman’s was so painful she says she’ll never get one again, another has heard too many stories to even try.

We laugh and drink more wine. This is mostly what – in my experience – women do with stories like this. They say: this happened, then this happened, and then they laugh. I don’t know why people say women aren’t funny. If there’s one thing women are good at, it’s making bad things into a joke. I see my friends doing it and myself laughing in reply. It’s only weeks later that I think: wait a minute, what did they say? What were they telling me?

When it’s my turn to share a story, I already have one waiting. I’ve told it before. It’s a funny one. I tell them about my bad experience with a GP and a speculum, and I laugh. Some of them wince or shake their heads. My friend – the good cook – is making a face.

That, she says, sounds like abuse.

Women with vaginismus will find it impossible to use a tampon, have a smear test or an ultrasound, or engage in any form of penetration in sex.

THREE

This is where I am now.

Vaginismus is the involuntary tightening of the muscles surrounding the vagina, making it impossible for anything to be put inside. It can be caused by abuse or trauma, but sometimes the reason it occurs is unexplained. Not much is known about it and not much is said.

I was diagnosed with vaginismus last year. There’s sometimes an assumption that the only thing it affects is sexual penetration in a heterosexual relationship, but this is not the case. Women with vaginismus will find it impossible to use a tampon, have a smear test or an ultrasound, or engage in any form of penetration in sex, whether that be a penis or a single finger. Writing this, right now, I’m in pain because, thinking about everything that’s happened, my brain is telling my body that’s what it should expect. Every time I work on this essay, I feel my body going into protective shutdown – clamping.

Roughly two in every thousand women suffer from vaginismus. I have been told to use a condom since I was 11, but I was never told that feeling pain at the mere thought of having sex was something that might happen to me.

I go for regular check-ups at the vulval pain clinic. I do three sets of ten pelvic floor exercises every (some) day(s). My partner has become a master at vaginal pep talks. We see a therapist together, so that we can understand what is happening. Friends who’ve experienced vaginismus tell me again and again about what happened to them, how it felt, how it will get better at least for a time. There is power in knowledge, in discussion. The pills I’ve been prescribed to ease the pain make me sleepy in the morning, zombie-like, grumpy. If I drink more than one glass of wine, the hangovers are barbaric and whole days are swallowed. Sometimes it is too much and my body is off limits even to myself. Some days are better. A lot of days are better. There is less despair; with understanding comes a sort of relief.

I show this essay to a friend and he says: did you know that, etymologically, the meaning of ‘trauma’ is ‘wound’? Every woman knows what it is like to laugh about something that isn’t funny, to experience harm from the places harm should not come from. These are small wounds, adding up to an enormous rage.

I told her I’d felt pain. She said that she had touched me so lightly most people would feel nothing.

FOUR

This is how it started.

I did some online dating and, after a while, I met someone and found myself in a relationship. I’d been making jokes about having bad sex for years but suddenly the sex was good in a way I’d never thought it could be.

About five months in, I started feeling pain during intercourse and was diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is an infection of the reproductive organs. There isn’t a sure-fire way of testing for PID, so mostly, if it’s suspected, it’s treated with antibiotics.

I took the antibiotics and was well again for a few months, but then the pain returned. I took more antibiotics. I also had an ultrasound and went back to the sexual health clinic. The clinic was good if you got a good doctor or nurse, but that wasn’t always the case so, somewhere around this time, I decided to visit my GP instead.

FIVE

I’m not good with faces but that GP is imprinted in my memory in the same way the sexual health clinic is. And if I die and go back to the clinic, I know he’ll be there waiting for me.

I don’t remember what time of year it was, but I think it was warm. I had been sitting in the waiting room and then I’d been called in. He’d looked like Christoph Waltz with an accent to match, though he was perhaps a little older. He seemed to find it hard to meet my eyes, scanned through things on his computer screen, made loud tapping notes. I should have known then that he wasn’t going to be any good.

He asked what the problem was and I explained about the PID and how I was still having pain even though I’d had antibiotics twice. I wasn’t embarrassed. I’d been talking to people about my vagina for a while now. But he seemed uncomfortable, which didn’t feel right and made me nervous. He asked how old I was. I told him. He asked me if I had a partner. “Yes,” I said. “How long?” “Two years.” “Oh,” he said. “Not long then.”

I knew then that he thought I had an STD. When my partner and I first got together we’d been tested, and I’d been tested again every time I went up to the sexual health clinic. When I was diagnosed with PID, my partner was tested too.

I tried to explain this to the doctor but he didn’t seem to hear me. He seemed purposeful now, certain he knew what was wrong. He said something like, chlamydia is very common for someone your age. He told me he’d like to take a look and would get a nurse.

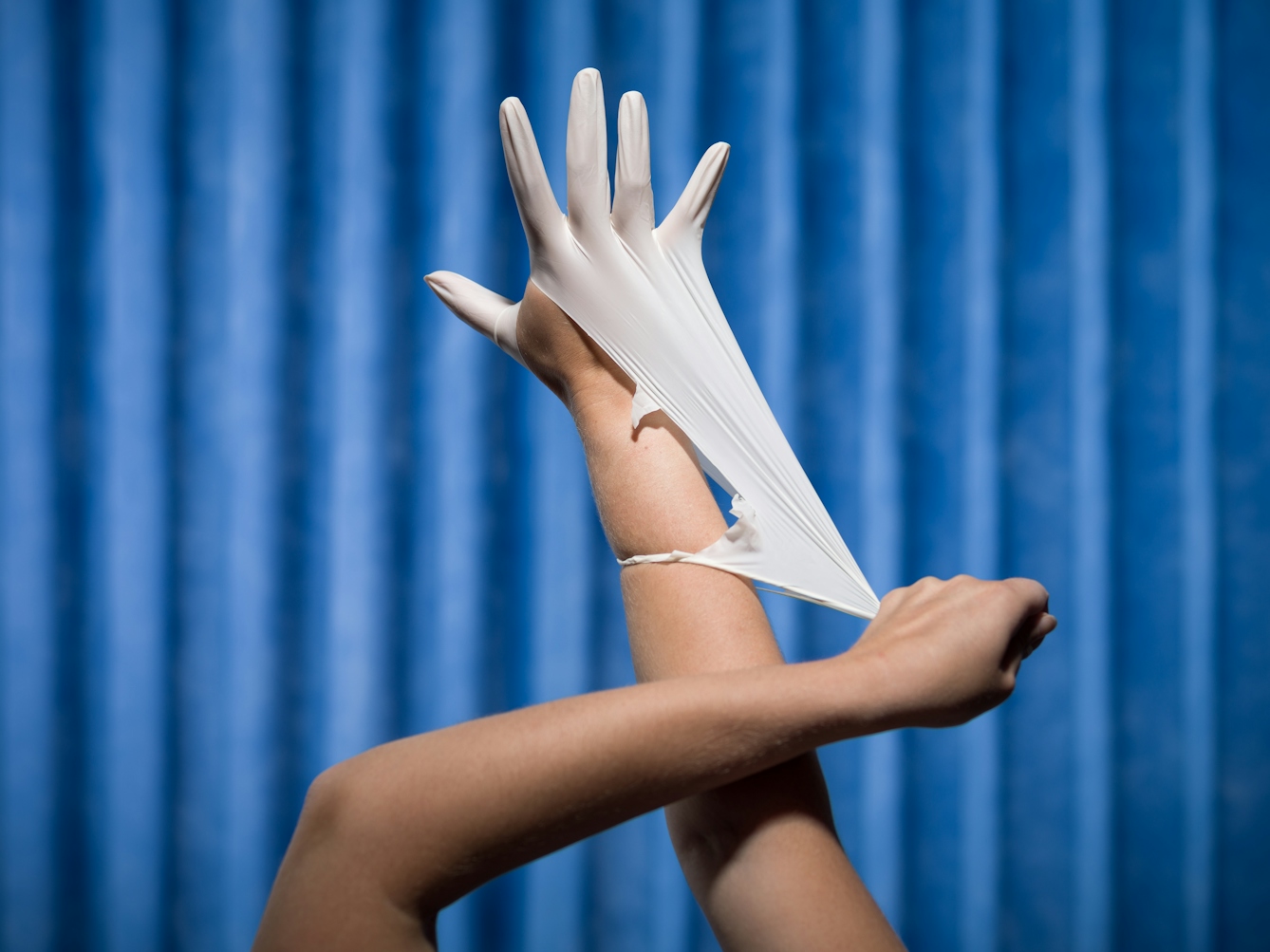

I lay on the examining table and the nurse stood by my head while he got the speculum ready. I could tell without looking that the speculum was either too big or he hadn’t put enough, if any, lubrication on it. I think I must have gasped or started to cry, because the nurse held my hand.

“This isn’t the right one,” he said, sounding annoyed, and he went back to looking in the tray of implements.

I think at this point I sat up. I was naked from the waist down and I was shaking all over. I sat up and I said, very loudly: “I’ve been tested and so has my partner and we were both negative.” He put the speculum down. He looked relieved. He could clearly see the end of the appointment in sight.

He gave me another month’s worth of antibiotics. He never met my eye. He’d just tried to force a too-big speculum into my vagina but he couldn’t meet my eye. I didn’t know what to say so, as I was leaving, I thanked him. I think a lot about all the things I could have said and how, instead of any of them, I thanked him.

This is the story I told at the dinner that night.

He never met my eye. He’d just tried to force a too-big speculum into my vagina but he couldn’t meet my eye.

SIX

After finishing that third course of antibiotics and still feeling pain when having sex or using a tampon, or simply, sometimes, just when I was sitting on the sofa or walking somewhere, I went back to the sexual health clinic. I was lucky this time. You shouldn’t have to be lucky when you go to the doctors, but this time I was.

It was a Monday and nearly the end of the day. I waited for a while and then saw a female doctor. She listened carefully to everything I had to say. She smiled, and she interacted with me without any sort of judgement or presumption. I told her that they’d thought I had recurring PID but that the pain wasn’t leaving, that it was there even when I wasn’t doing anything I could see that would cause it. She asked me to describe it and I told her it was like a clamp tightening. She asked to examine me. She touched my vulva with a cotton bud. She gently put a finger inside me.

When I was dressed, she asked what I’d felt and I told her I’d felt pain. She said that she had touched me so lightly most people would feel nothing. She also said that when she’d inserted a finger the strong muscle at the entrance to my vagina had tightened. She explained that she was certain I had vaginismus. That it was probable that the PID had been misdiagnosed at least once. She arranged an appointment with a psychosexual therapist and put me on an extremely low dose of antidepressants often used for pain relief.

The psychosexual therapist wore motorcycle boots. She slumped down in her chair and together we did pelvic floor exercises designed to make that strong, unbearable muscle relax. I held a breath in my belly for two seconds and then released.

I’m not certain what it was about these two doctors that made them better than all the others. Perhaps it was the way they listened as soon as I walked into the room, looked me in the eye, didn’t dismiss me when I told them about my inept searches on the NHS website, the panic that began as soon as I woke, the fear that something bigger was wrong, that I would never be able to have children or maintain a sexual relationship. Or the way that, when they were talking to me, they didn’t seem evasive or in a hurry, they didn’t offer antibiotics as soon as they could, or seem to want to get me out of the room.

There is a dichotomy between the words we use and those that are forbidden because they are embarrassing or shameful.

SEVEN

After the dinner party, I lay in bed trying to sleep and I thought about lying on the GP’s examining table and having something forced into my vagina that was too big to fit.

Discussing it with the psychosexual therapist, we’d decided that the vaginismus had come from the bouts of PID and a growing fear of pain that had switched my brain into panic mode. I’d mentioned the examination with the GP but it hadn’t seemed important at the time. It wasn’t until I saw my friend’s face across her coffee table, the frown lines on her forehead, that I even considered it might have been more than that. Might, if not solely, have been part of the problem. I do not think he did it out of malice or some skewed form of pleasure, a need to take whatever I wasn’t willing to give; I think it was ineptitude, at worst, a lack of care that resulted in pain.

EIGHT

There are things we don’t talk about or, if we do, we downplay them, hide them beneath blather and jokes. There is a dichotomy between the words we use and those that are forbidden because they are embarrassing or shameful. There are women out there who feel pain every time they try to use a tampon, or even think about having sex, and they may never know that these are things other women experience, too. There are women out there who will never get a smear test because the pain they experience when they do is enormous and unexplained. Under the sound of their laughter is a sort of plea: listen to me.

NINE

I went to the same doctors’ surgery in December to renew my prescription. It was one of those grisly snow days, the pavements hardened to ice, nearly Christmas. I imagined what I would say to that GP if I saw him. I’d planned the words in the shower, and working at my desk, and walking along the river by my house. The words were enormous, great balloon animals in my head. I would say: “This is what it’s like to have a vagina. This is what it’s like when no one listens when you tell them to stop.”

About the contributors

Daisy Johnson

Daisy’s debut short-story collection, ‘Fen’, was published by Cape in the UK and by Graywolf in the US. Her novel ‘Everything Under’ has been shortlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize. She was the winner of the Edge Hill Prize, the AM Heath Prize and the Harper’s Bazaar short-story prize, and has been longlisted for the Sunday Times Short Story Prize and the New Angle Prize. Daisy currently lives in Oxford.

Benjamin Gilbert

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.