In the 19th century, groups of European colonialists attempted to ‘improve’ on nature by introducing non-native species all over the world. These ‘acclimatisation societies’ could hardly have envisaged the disastrously expensive environmental havoc they had unleashed.

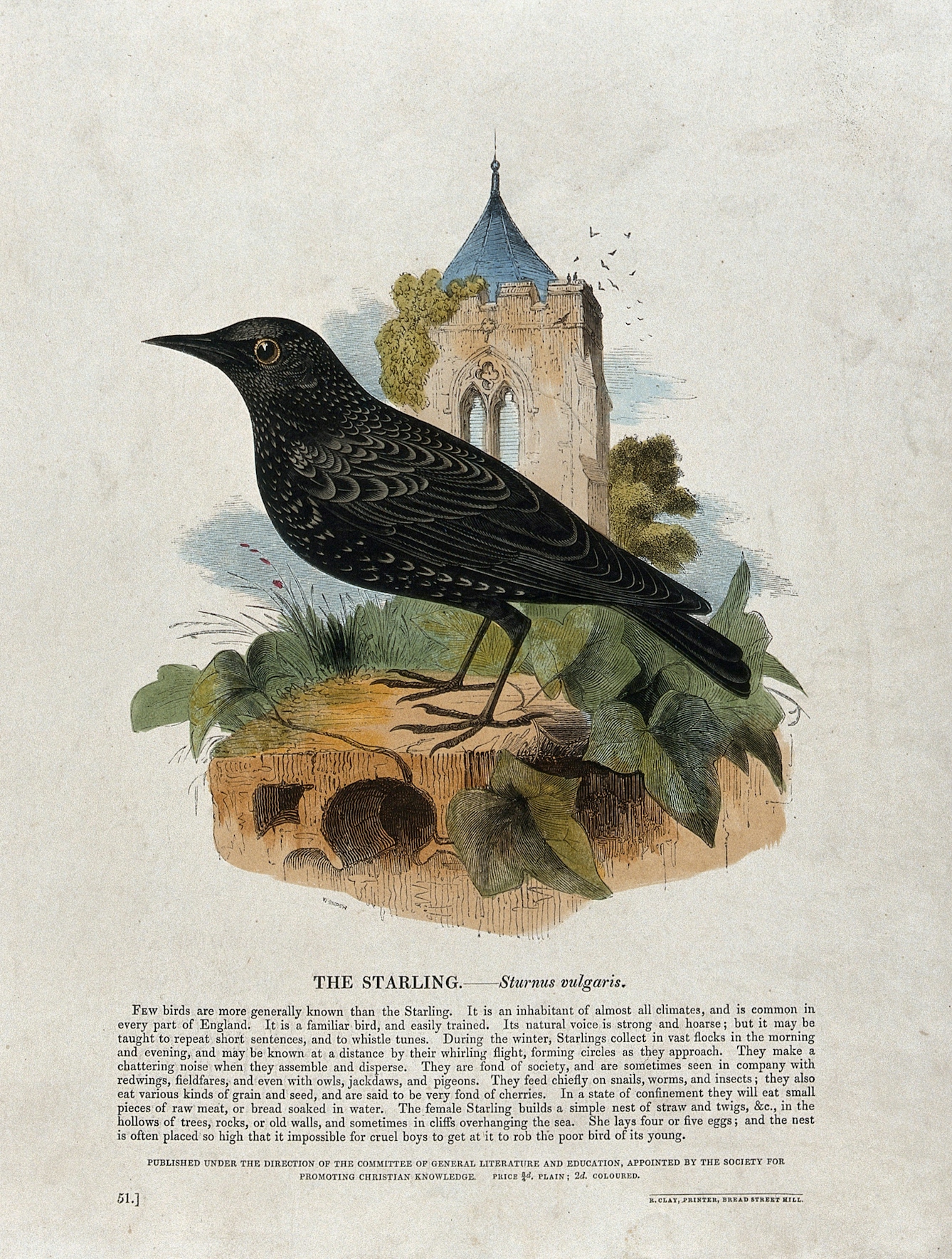

The ubiquity of the boisterously noisy starling in the United States is often blamed on one man. On 6 March 1890, Eugene Schieffelin released around 60 European starlings in New York’s Central Park, supposedly, the oft-repeated story goes, on a mission to introduce to the country every bird mentioned by Shakespeare.

Coloured wood engraving of a starling.

The now unpopular bird, its feathers the iridescent colour of an oil slick, was an annoyance even in the Bard’s Henry IV, when Hotspur contemplates training a starling to torment the king, who refuses to pay to free his brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer: “I'll have a starling shall be taught to speak/Nothing but ‘Mortimer’, and give it him/To keep his anger still in motion.”

Schieffelin was not an eccentric loner causing ecological mayhem. He was a member of the American Acclimatization Society, started in 1871 to deliberately introduce “such foreign varieties of the animal and vegetable kingdom as may be useful or interesting”. By 1877, according to the New York Times, the society had released into the New York area English sparrows, Java sparrows, English skylarks, Japanese finches, and, yes, starlings years before that day in Central Park so frequently cited as the beginning of the avian invasion.

Now starlings have an estimated North American population of 200 million, pushing out native species like the eastern bluebird and damaging millions of dollars-worth of crops each year.

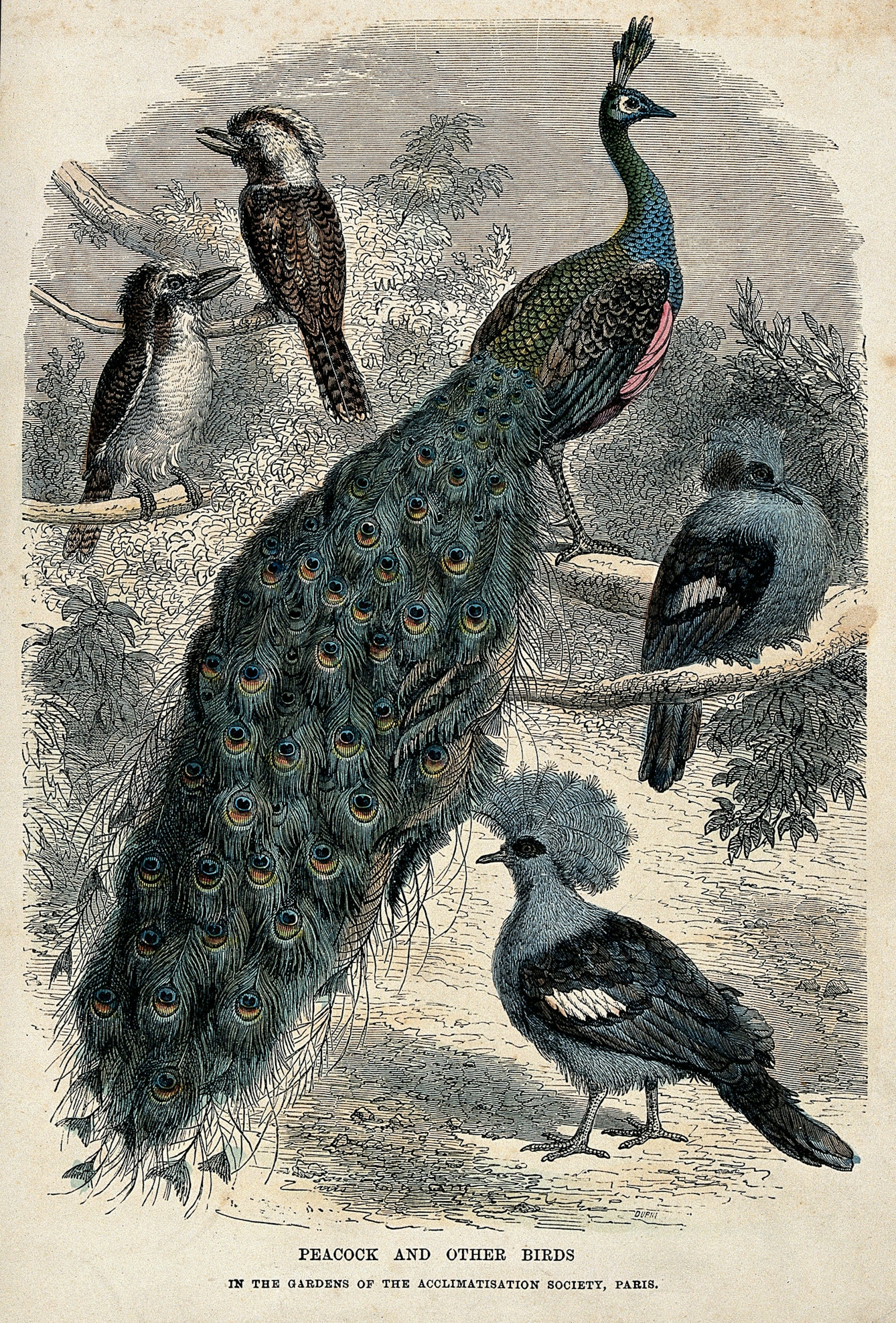

Au jardin d'acclimatation, The New York Public Library, 1852–1882.

An idealistic animal exchange

The starling is only one story in a 19th-century global movement to release exotic species with the intent of improving an environment. While domestication of non-native flora and fauna was for centuries part of agriculture, these acclimatisation societies elevated the ecological visions of individuals.

The first was founded in 1854 in Paris by naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. In the Jardin d’Acclimatation, animals like yaks and Angora goats were raised with the idea of introducing them to France. Saint-Hilaire imagined a global trade of useful creatures, wondering: “We have given the sheep to Australia; why have we not taken in exchange the kangaroo – a most edible and productive creature?” At one point his Paris zoo had 11,000 animals. Unfortunately, during the 1870 Siege of Paris, many were consumed by hungry citizens, including the African elephants Castor and Pollux.

Etching of a kangaroo.

Breeding like rabbits

Still the acclimatisation societies spread, particularly in the British colonies. Most of the animals they introduced were envisioned as food, such as pheasants and trout. Edward Wilson, first president of the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria, thought Australia’s indigenous creatures were only good for “a little sport and an occasional meal”. One of the society’s members, Englishman Thomas Austin, released 24 rabbits in 1859, writing: “The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.”

Coloured wood engraving of a hare.

Coloured wood engraving of the Acclimatisation Society gardens in Paris showing peacocks and other birds.

Other farmers subsequently freed their own rabbits, so that by 1950 there were 600 million in Australia. Despite eradication attempts like the introduction of the myxoma virus and a rabbit-proof fence stretching hundreds of miles to stop their rampant consumption of plants, rabbits persist as a pest.

An unintended invasion

The Acclimatisation Society of Victoria’s 1874–5 tally of “stock liberated” included 110 pheasants, 120 Californian quail, 15 Indian grey partridges, 3 English partridges, 18 hares, 800 carp, 300 perch, and 300 pheasant eggs that “were distributed to Members of the Society”. Survival results were mixed, as were the benefits. The society’s 1872 report laments the difficulties of domesticating African ostriches: “When turned out of the paddock, they gradually got wilder, and as they ran faster than a horse, it was most difficult to get them in the yard again to take their feathers from them.”

Acclimatisation societies are just one iteration of the human impulse to augment the environment to better serve our needs. But their good intentions have resulted in enduring ecological turmoil in many parts of the world. For as long as starlings darken the North American skies, and bunnies bound across Australia, those Victorians’ decisions will haunt the environments of the present.

About the contributors

Allison C Meier

Allison C Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer who focuses on history and visual culture. She was previously Senior Editor at Atlas Obscura and more recently a staff writer at Hyperallergic.